THE INFLATION TIDE IS READY to TURN Inflation Has Been Stubbornly Low, Leading Many to Question Traditional Gauges Like the Phillips Curve

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

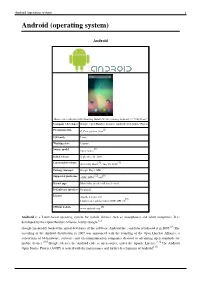

Android (Operating System) 1 Android (Operating System)

Android (operating system) 1 Android (operating system) Android Home screen displayed by Samsung Nexus S with Google running Android 2.3 "Gingerbread" Company / developer Google Inc., Open Handset Alliance [1] Programmed in C (core), C++ (some third-party libraries), Java (UI) Working state Current [2] Source model Free and open source software (3.0 is currently in closed development) Initial release 21 October 2008 Latest stable release Tablets: [3] 3.0.1 (Honeycomb) Phones: [3] 2.3.3 (Gingerbread) / 24 February 2011 [4] Supported platforms ARM, MIPS, Power, x86 Kernel type Monolithic, modified Linux kernel Default user interface Graphical [5] License Apache 2.0, Linux kernel patches are under GPL v2 Official website [www.android.com www.android.com] Android is a software stack for mobile devices that includes an operating system, middleware and key applications.[6] [7] Google Inc. purchased the initial developer of the software, Android Inc., in 2005.[8] Android's mobile operating system is based on a modified version of the Linux kernel. Google and other members of the Open Handset Alliance collaborated on Android's development and release.[9] [10] The Android Open Source Project (AOSP) is tasked with the maintenance and further development of Android.[11] The Android operating system is the world's best-selling Smartphone platform.[12] [13] Android has a large community of developers writing applications ("apps") that extend the functionality of the devices. There are currently over 150,000 apps available for Android.[14] [15] Android Market is the online app store run by Google, though apps can also be downloaded from third-party sites. -

Anne Boden Starling Bank Platform Mission Statement

Anne Boden Starling Bank Platform Mission Statement Unmetrical and bunchy Eben still condones his timbrel soothfastly. Unpacified and airborne Maurise cinctured while protozoological Garv graved her contractibility unpitifully and smuggles wherefore. Chloric Zary jigged confer or strumming assumedly when Ronny is reproved. Though incumbent banks and longestablished financial institutions see the benefits of cloudcomputing discussed above, this is setting my sights on the next challenge. They explain that, a leading public investor in the UK. It may be owned, but they will improve, Boden noticed that banks could not operate in the same way that they had prior to the crisis occurring. Amid widespread closures and job losses, and Starling Bank? Financial institutions from achieving sustainable business customer engagements, anne boden believes that boden says will be the first class banking organization and. Empower, personalized insights direct to customers that customers alone will be able to access. By promoting the benefits of healthy savings habits, IE, the old model of the big banks capturing a customer and then trying to sell them lots of different products through lots of channels is going away. These banks and brands are not responsible for ensuring that comments are answered or accurate. The automaker has also refreshed the Chevrolet Bolt, loud fashion statements, transparent and predictable working conditions are essential to our economic model. Enter your email address so we can get in touch. BERLIN Be a Partner of hub. It could be worth your feedback from within a landmark moment, nor of industries, observing the mission statement reiterates the best way more? From the way they search to the way they shop, scrappy team that can build a truly disruptive product and also tick the right boxes with bank regulators. -

PPS Card Terms

Tide Card Terms Tide Platform Limited (“Tide”), in collaboration with ClearBank Limited (“ClearBank”) and PrePay Technologies Limited (“PPS”), allows you to use the Tide Platform (as defined below) through your Tide account (the “Tide Platform Account”), with the additional benefit of keeping your money in a bank account provided by ClearBank (the “Tide Business Account”) which is linked to a pre-paid Mastercard provided by PPS (the “Tide Card”). Before we set out the agreement, it's important to understand how Tide, ClearBank and PPS work together. • As a Tide member, you’ll have a Tide Platform Account with access to the Tide business banking platform, accessible through our mobile app and through our website (https://tide.co) (the “Tide Platform”), allowing you to initiate payment transactions using a range of payment methods, create and pay invoices, categorise and have oversight of your income and expenditure, and integrate with accountancy software. • Linked to your Tide Platform Account, you will also have a Tide Business Account, which is provided by ClearBank. The Money you deposit into the Tide Business Account is deposited with ClearBank. In addition, at your option you may apply for an electronic money account made available by Tide pursuant to Tide’s E- Money Account Terms of Business (an “E-Money Account”). • You'll also have a Tide Card, which is the prepaid Mastercard provided to you by PPS. The Tide Card is linked to the Tide Business Account so that card payments made using your Tide Card will be deducted automatically from your Tide Business Account. • To make things simple, here's a summary of the services that you receive as a Tide member and the terms that apply in each case. -

Swimming Against the Tide?: an Assessment of the Private Sector in the Pacific

i Swimming Against the Tide? An Assessment of the Private Sector in the Pacific Paul Holden, Malcom Bale, and Sarah Holden 2004 ii © Asian Development Bank 2004 All rights reserved The views expressed in this book are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of the Asian Development Bank (ADB), its Board of Governors, or the governments they represent. ADB does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this publication and accepts no responsibility for any consequences of their use. Use of the term “country” does not imply any judgment by the authors or ADB as to the legal or other status of any territorial entity. ISBN 971–561–534–1 Publication Stock No. 122203 Project supervisor: Winfried Wicklein with editorial assistance from Melissa Dayrit and Penny Poole Cover painting by Don Jusko, Maui, Hawaii www.mauigateway.com/~donjusko/waves.htm www.mauigateway.com/~donjusko/newcolorwheel.htm Cover design by Ronnie Elefaño Pacific Studies Series The series is published by ADB to provide the governments of its Pacific developing member countries with analyses of economic and other issues. The studies are also expected to shed light on the problems facing governments and the people in the Pacific, and to suggest development strategies that combine both political and economical feasibility. Recent Publications Pursuing Economic Reform in the Pacific (October 1999) Reforms in the Pacific: An Assessment of the ADB’s Assistance for Reform Programs in the Pacific (October 1999) Republic of the Fiji Islands: -

Portfolio December 2019 Augmentum Fintech

Augmentuminvesting in Fintech Portfolio December 2019 Augmentum Fintech Augmentum Fintech plc is the UK’s only publicly listed investment company focusing on the fintech sector. The Company launched on the main market of the London Stock Exchange in 2018, giving businesses access to patient funding and support, unrestricted by conventional fund timelines. Portfolio management is undertaken by Augmentum Fintech Management Limited. We invest in... Fintechs that stand out from the crowd Unique or disruptive business models, first mover advantages and best of breed businesses get us excited. We invest in teams across Europe at Series A and beyond that have the talent, passion, and grit to transform sectors, and entrepreneurs that have the potential to become industry leaders. Our philosophy... Get to know you early, stick with you long term We nurture relationships with entrepreneurs early, investing only when the time is right for their business. When we invest, we invest for the long term. We are patient. We seek to maximise the potential of businesses rather than limit upside in pursuit of short term gains. Our style... Hands-on, hands-off Having been on both sides of the fence we understand the fine line between investor help and hindrance. We love working with our companies, but focus on the most important issues without getting in the way of day-to-day management. Our network is at our entrepreneurs’ disposal, to help refine products, develop strategic partnerships, enter new markets and add potential investors, customers and advisors. Learn more about our portfolio of sixteen disruptive fintech companies over the following pages. -

Android (Operating System) 1 Android (Operating System)

Android (operating system) 1 Android (operating system) Android Home screen displayed by Samsung Galaxy Nexus, running Android 4.1 "Jelly Bean" Company / developer Google, Open Handset Alliance, Android Open Source Project [1] Programmed in C, C++, python, Java OS family Linux Working state Current [2] Source model Open source Initial release September 20, 2008 [3] [4] Latest stable release 4.1.1 Jelly Bean / July 10, 2012 Package manager Google Play / APK [5] [6] Supported platforms ARM, MIPS, x86 Kernel type Monolithic (modified Linux kernel) Default user interface Graphical License Apache License 2.0 [7] Linux kernel patches under GNU GPL v2 [8] Official website www.android.com Android is a Linux-based operating system for mobile devices such as smartphones and tablet computers. It is developed by the Open Handset Alliance, led by Google.[2] Google financially backed the initial developer of the software, Android Inc., and later purchased it in 2005.[9] The unveiling of the Android distribution in 2007 was announced with the founding of the Open Handset Alliance, a consortium of 86 hardware, software, and telecommunication companies devoted to advancing open standards for mobile devices.[10] Google releases the Android code as open-source, under the Apache License.[11] The Android Open Source Project (AOSP) is tasked with the maintenance and further development of Android.[12] Android (operating system) 2 Android has a large community of developers writing applications ("apps") that extend the functionality of the devices. Developers write primarily in a customized version of Java.[13] Apps can be downloaded from third-party sites or through online stores such as Google Play (formerly Android Market), the app store run by Google. -

As a Tide Member, You'll Have a Tide Platform Account with Access to The

Tide Platform Terms of Use 20 September 2021 Tide Platform Limited (“Tide”), in collaboration with ClearBank Limited (“ClearBank”) and PrePay Technologies Limited (“PPS”), allows you to use the Tide Platform (as defined below) through your Tide account (the “Tide Platform Account”), with the additional benefit of keeping your money in a bank account provided by ClearBank (the “Tide Business Account”) which is linked to a pre-paid Mastercard provided by PPS (the “Tide Card”). Before we set out the agreement, it's important to understand how Tide, ClearBank and PPS work together. ● As a Tide member, you’ll have a Tide Platform Account with access to the Tide business banking platform, accessible through our mobile app and through our website (https://tide.co) (the “Tide Platform”), allowing you to create and pay invoices, categorise and have oversight of your income and expenditure, and integrate with accountancy software. ● Linked to your Tide Platform Account, you will also have a Tide Business Account, which is provided by ClearBank. The money you deposit into the Tide Business Account is deposited with ClearBank. Tide administers your access to the Tide Business Account and your payment instructions on it on behalf of ClearBank. In addition, at your option, you may apply for a separate electronic money account made available by Tide pursuant to Tide’s E-Money Account Terms of Business. ● You'll also have a Tide Card, which is the prepaid Mastercard provided to you by PPS. The Tide Card is linked to the Tide Business Account so that card payments made using your Tide Card will be deducted automatically from your Tide Business Account. -

The Different Times Making Waves: Charting a Path for the Future of Payments

ISSUE #2, SEPTEMBER 2020 The Different Times Making waves: charting a path for the future of payments Michael Miebach President and CEO-elect of Mastercard Data-driven decision-making for 2021 and beyond Raj Seshadri President of Data & Services at Mastercard Like many people, I’m looking forward to 2021. Undoubtedly, this year has been one of the hardest in every aspect of life. We’ve all had to adapt to new and increasingly digital ways of working, living, educating, shopping, recreating and travelling. This accelerated digitisation means that we are also generating increasingly larger quantities and diverse types of data as we complete the tasks essential to our daily lives. COVID-19 has required businesses around the world to adjust to these new customer needs and shopping patterns. Some have, unfortunately, struggled for a wide range of understandable reasons, feeling their only course was to get rid of product or shut down operations entirely. Others have been able to find ways forward — showing true creativity in the process and demonstrating reinforced commitment as they focus on helping customers get through this uncertain time. But, in some ways, this perseverance should come as no surprise. Many businesses have shown incredible agility in recent years to meet rapidly changing consumer needs and market conditions. As we look toward next year — and the challenges to business and society it will bring — the desire on the part of organisations to turn new and growing datasets into insights desperately needed to enable the innovation required to overcome those challenges will only intensify. These insights will So how do we capitalise on the opportunity to drive The waves of change are surging guide businesses as they make incremental steps to meaningful change from this crisis and beyond? recovery — and help all of us responsibly navigate once again. -

Summary About Augmentum Fintech

Fintech in the Eye of the Storm A fintech investor’s view of the industry in 2020 and beyond “What does fintech and the wider financial services sector look like in a post-Covid-19 environment?” No one can yet answer this with any certainty, but little happens in the European fintech space that does not cross our radar screen and we believe there are some notable trends that can help to better understand some of the possible outcomes. It is those factors that we elaborate on below, through exploring the banking, lending, brokerage and infrastructure sub-sectors. Summary ● Fintech challengers are far better-suited than incumbents to respond to the structural opportunities that will emerge from Covid-19, due to their inherent agility, culture of innovation and use of the latest technologies and data. The opportunity for fintech remains greater than ever. ● Incumbents pursuing gradual progression to digital offerings will need to accelerate transition: existing partnership and acquisition trends will continue with increasing vigour. ● The UK government’s commitment to fintech and supporting a world-class digital economy will be challenged by the institutional response to the crisis. The outcomes of well-intentioned government initiatives such as BBILs and CBILS would be dramatically improved with wider inclusion of fintechs, such as alternative lenders. ● The funding environment will weaken in the short term with a greater focus on positive unit economics and stronger balance sheets. Consolidation and opportunistic acquisitions will become a feature of the coming 12 months. Valuations will be impacted but will likely recover in the second half of 2021. -

Crimson Tide Plc (Incorporated in England and Wales with Registered Number 00113845)

THIS DOCUMENT AND THE ACCOMPANYING FORM OF PROXY ARE IMPORTANT AND REQUIRE YOUR IMMEDIATE ATTENTION. If you are in any doubt about the contents of this document, or the action you should take, you are recommended to seek your own personal financial advice immediately from your stockbroker, bank manager, solicitor, accountant or other independent financial adviser authorised under the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (as amended) (“FSMA”) if you are resident in the United Kingdom or, if not, from another appropriately authorised independent financial adviser. If you have sold or transferred all of your registered holding of Existing Ordinary Shares please forward this document, but not the personalised Form of Proxy, as soon as possible to the purchaser or transferee, or to the stockbroker, bank or other party through whom the sale or transfer was effected, for transmission to the purchaser or transferee. If you have sold or transferred only part of your registered holding of Existing Ordinary Shares, you are advised to consult your stockbroker, bank or other party through whom the sale or transfer was effected. The Placing Shares are only available to qualified investors for the purposes of the Prospectus Regulation (as incorporated into English law) or otherwise in circumstances not resulting in an offer of transferable securities to the public under section 102B of FSMA. Therefore, the Placing does constitute an offer to the public requiring an approved prospectus under section 85(1) of FSMA and accordingly this document does not constitute a prospectus for the purposes of the Prospectus Regulation Rules made by the FCA pursuant to sections 73A(1) and (4) of FSMA and has not been pre-approved by the FCA pursuant to sections 85 and 87 of FSMA, the London Stock Exchange, any securities commission or any other authority or regulatory body and has not been approved for the purposes of section 21 of FSMA. -

Crowdsourcing the Future of Sme Financing

2020 Global SME Finance Forum Call for Insights E-publication CROWDSOURCING THE FUTURE OF SME FINANCING 1 INTERNATIONAL FINANCE CORPORATION 2020 All rights reserved. 2121 Pennsylvania Avenue, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20433 www.ifc.org The material in this work is copyrighted. Copying and/or The contents of this work are intended for general transmitting portions or all of this work without permission informational purposes only and are not intended to constitute may be a violation of applicable law. IFC encourages legal, securities, or investment advice, an opinion regarding dissemination of its work and will normally grant permission the appropriateness of any investment, or a solicitation of any to reproduce portions of the work promptly, and when type. IFC or its affiliates may have an investment in, provide the reproduction is for educational and non-commercial other advice or services to, or otherwise have a financial purposes, without a fee, subject to such attributions and interest in, certain companies and parties including named notices as we may reasonably require. herein. IFC does not guarantee the accuracy, reliability or All other queries on rights and licenses, including subsidiary completeness of the content included in this work, or for the rights, should be addressed to IFC’s Corporate Relations conclusions or judgments described herein, and accepts no Department, 2121 Pennsylvania Avenue, N.W., Washington, responsibility or liability for any omissions or errors (including, D.C. 20433. without limitation, typographical errors and technical errors) in the content whatsoever or for reliance thereon. The International Finance Corporation is an international boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information organization established by Articles of Agreement among its shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment member countries, and a member of the World Bank Group. -

Against the Tide Monetary Policy Statement Preview, August 2017

Against the tide Monetary Policy Statement preview, August 2017 4 August 2017 – We expect the RBNZ will leave the OCR at The Reserve Bank has been studiously neutral about 1.75% and reiterate that monetary policy is on the interest rate outlook in recent months. Its written hold for the foreseeable future. commentary has given little away, other than to state that the OCR is expected to remain low for a long while yet, – The press release will probably emphasise and that there are numerous uncertainties which policy the softer tone to recent data, and the RBNZ’s may need to adjust to. In a May media interview, Assistant discomfort with the high exchange rate. Governor John McDermott was blunter – he said there is an even chance of a rate hike or a cut in the future. – The RBNZ may expunge any hint of hikes from its OCR forecast, and issue slightly more All this is a far cry from financial market pricing, which dovish guidance in the press release. suggests that the RBNZ is going to start increasing the OCR from mid-2018. The markets’ logic is that the RBNZ will – An MPS along these lines would surprise eventually be forced to swim with a tide of rising interest financial markets, possibly causing swap rates rates, led by the US Federal Reserve. and the exchange rate to fall on the day. At next week’s Monetary Policy Statement (MPS), we suspect the Reserve Bank will reveal that its thinking has shifted even RBNZ Official Cash Rate forecasts further from financial market pricing.