Pson Learning Thomp © PHOTODISC Chapter 2 Organizations and Managerial Challenges in the Twenty-First Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Big Consumer Brands Can Do to Compete in a Digital Economy

WHAT BIG CONSUMER BRANDS CAN DO TO COMPETE IN A DIGITAL ECONOMY HOWARD YU ON HOW CONSUMER BRANDS CAN ESCAPE THE RETAIL WASTELAND – FROM HARVARD BUSINESS REVIEW By IMD Professor Howard Yu This article was originally published on HBR.org IMD Chemin de Bellerive 23 PO Box 915, CH-1001 Lausanne Switzerland Tel: +41 21 618 01 11 Fax: +41 21 618 07 07 [email protected] www.imd.org Copyright © 2006-2018 IMD - International Institute for Management Development. All rights, including copyright, pertaining to the content of this website/publication/document are owned or controlled for these purposes by IMD, except when expressly stated otherwise. None of the materials provided on/in this website/publication/document may be used, reproduced or transmitted, in whole or in part, in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or the use of any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from IMD. To request such permission and for further inquiries, please contact IMD at [email protected]. Where it is stated that copyright to any part of the IMD website/publication/document is held by a third party, requests for permission to copy, modify, translate, publish or otherwise make available such part must be addressed directly to the third party concerned. No industry is failing faster than retail. Recently, the 125-year-old Sears—once the world’s largest retailer—filed for bankruptcy. The public has more or less come to expect the shuttering of stores such as Macy’s, Sears, Toys ‘R’ Us, Kmart, Kohl’s, J.C. -

141Journal-1.Pdf

1 Table of Contents Clergy of the Diocese List of Lay Delegates 4 Minutes 17 Appendices 23 A: Rules of Order B: Bishop’s Address to Convention C: Reports 51 William Cooper Procter Fund 58 Statistics 63 79 Budget 86 Constitution and Canons 92 101 About this Journal: The Journal for the 141st Annual Convention of the Diocese of Southern Ohio includes minutes and reports from the November 13-14, 2015 gathering at the Dayton Convention Center in Dayton, Ohio, as well as the Constitutions and Canons of the Diocese of Southern Ohio. The complete Journal is available online at http://diosohio.org/who-we- are/conventions/convention-archives/. Printed copies of this Journal will be sent only to The Episcopal Church Center and others for archival purposes. Although the Journal is copyrighted, copies may be made for parishioners, church staff or those affiliated with diocesan ministries. For questions, feedback or more information, contact the communications office of the Diocese of Southern Ohio at 800.582.1712 or email [email protected]. © 2016 by the Diocese of Southern Ohio Communications Office, 412 Sycamore Street, Cincinnati, OH 45202. All Rights Reserved. 3 Clergy of the Diocese of Southern Ohio, in order of Canonical Residence as of November 6, 2015 Albert Raymond Betts, III June 15, 1955 William George Huber May 31, 1958 William Norton Bumiller June 10, 1958 John Leland Clark October 29, 1958 Charles Randolph Leary September 1, 1959 Edward Noyes Burdick, II July 1, 1960 David Knight Mills September 19, 1960 Lawrence Dean Rupp June 25, 1961 Christopher Fones Neely August 8, 1961 Jack Calvin Burton June 15, 1963 John Pierpont Cobb October 28, 1963 Frederick Gordon Krieger December 26, 1963 Jerome Maynard Baldwin March 1, 1964 David Ormsby McCoy June 13, 1964 Frank Beaumont Stevenson June 13, 1964 Albert Harold MacKenzie, Jr. -

Divergent Reports Made to House on Dr. Wirt's Charges

- r l , VOL. U I I .n o . 181. (ClMtlflcd AdvwIMaf oo F f M.), MANCHESTER, CONN., WEDNEdOAY, MAY 2, 198A (SIXTEEN PAGES) PRICE THREE CENTS. FIRE RUINS TURN FRENCH REPORT Radicals Parade Might On New York’s May Day STABILIZATION DIVERGENT REPORTS HALL, CENUR OF NEW SPY PLOT; FUND PUZZLES fl MADE TO HOUSE ON poLisHjnvnr A i m AGENT ■ 'M xJA x 'A -Xy WAU^STREET Kg Wooden Stroctare On Declare Organizadoo If At ' '.'A BeBeye It U New Move of DR. WIRT’S CHARGES North SL Is D estroy^ Large at Other ia Whidi Major Importance But Not TREASURY REPORTS Majority Condndes There Early Today — Fironon Two Americant Were Just Certain Wbat It Is. Was No Fonodation f « ^ ' 1 ON EXPEMOnURES Sare Adjacent Homes. Implicated. J -.y ' . Some Opinions. Educator’s Assertions —t Turn HaII, center of social sad Paris, May 2.—(AP)—Police an New York, May 2,—(AP) —For Spent Only Litde More Than Minority Claims Probe athletic activities among the Polish nounced today that a huge “ Ger : ....... mal setting up of the Treasury’s residents of Mimchester, was de man spy organization" had been un ty'- V : 'A'/A■.■Z't yf $2,000,000,000 stabilization fund this Half of What Had Been Was Not Thorongh stroyed by fire early this morning. covered with the arrest of an agent week hM Wall street wondering If The large wooden building, at 71 in Paris and that warrants bad some new monetary move of major North street, housed. In addition to ' " ^ .X Enough. been issued for Aber members of moment is In the making. -

Mar" Fum out of the Way ; And

THE TEBSDALE iiERCUKT—WEDNESDAY, MAY 3, 1007. i "Don't! I only follow the custom of my OUR SHORT STORY. country," uttered the girl indignautly. GUARDIANS ON TRIAL. GREAT NAVAL DISPLAY. BOOKS AND MAGAZINES. "As I «ef mine. Oh, you are right. We [iu Eiara Sum two will be revenged—we two together—my One of the most realistic of the many naval A BITTER REVENGEVENf E love. What says the soug— At the Central Criminal Court Mr. Jus THE U.S. AND BRITAIN. tice Jelf continued the trial of ten West Ham spectacles given at Portsmouth was provided "Will the British Empire stand or fall?" asks "They please me all, Guardians and Poor Law officials charged on Friday in honour of the visit of the Colonial I FOR GO: How beautifully lay n ^Rttar ftay They please me all, Premiere to the Empire's greatest naval port. Mr. J. Ellis Barker in the "Nineteenth Cen shadow as a carriagerul olHptty girls and with conspiracy to defraud in connection THE STORY| But the fair-haired girls The Colonial visitors were escorted by a host tury. " Then he puts another query: " Will their chaperon drove down from the old with contracts for the West Ham Union. They please me best." of peers, members of Parliament, and other Great Britain be able to continue maintaining Moorish castle, bound to the Governor's ball. Five of the Guardians — Crump, Anderson, notable persons, both official and unofficial, the her naval supremacy against Germany and the "O che rubia (What a fair one)!" And next Skinner, Watts, and F. -

Spanish American, 06-26-1920 Roy Pub Co

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Spanish-American, 1905-1922 (Roy, Mora County, New Mexico Historical Newspapers New Mexico) 6-26-1920 Spanish American, 06-26-1920 Roy Pub Co. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/sp_am_roy_news Recommended Citation Roy Pub Co.. "Spanish American, 06-26-1920." (1920). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/sp_am_roy_news/378 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the New Mexico Historical Newspapers at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Spanish-American, 1905-1922 (Roy, Mora County, New Mexico) by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. University "'v I' 'M TTT TT M 1LJ if Air "Wi'Jb Malice toward None, with Charity for All, and with Firmness in the Right" Volume XYiTT ROY, Mora County, New Mexico, Saturday. June 6, 1920. "Number 24 fUIMIM,,Mt,lIMl""l,llMI,''...t.I,t,(,lMM June 18, 1920. 'ltlllitlltllltllllllMlliilltaiila..taallllitlljtillllliaia,i School News TO CITY AND COUNTY HEALTH Ball Game Stone's Party i .OFFICERS: The ball game Sunday between Roy Mr. and Mrs. Henry Stone enter- 1 1 The Roy School Board closed a There lias been an outbreak of BU- - ! I and Dawson teams on the. Roy dia- tained their friends at their ranch very satisfactory contract with J. C. BONIC PLAGUE in Mexico and sev-- Personal Mention Amarillo, mond, was one to be proud of even home in La Cinta Canyon Saturday Berry & Co., Architects, of eral cases have appeared upon the ; though Roy did lose. -

Wwd011411.Pdf

2 WWD, FRIDAY, JANUARY 14, 2011 WWD.COM Prada Opening Offices retail In Paris and Hong Kong Target Gets Northern Exposure By DAVID MOIN for Lord & Taylor in 2006. NRDC’s roots are By LUISA ZARGANI in real estate, so its recent acquisitions of re- Target is getting set to invade Canada, and in tailers have raised speculation that real es- MILAN — Prada is taking its design team east and west. a big way. tate owned by the retailers could be sold off. In a groundbreaking move, the luxury goods house said it plans to America’s trendy discounter will open 100 With many of its sites going to Target and open two new design and research offices in Paris and Hong Kong, the to 150 stores across Canada in 2013 and 2014, possibly other retailers, Zellers, currently first outside company headquarters here. The offices will be complemen- through a $1.84 billion deal to take over up to with 279 locations, will become a much- tary to and coordinated by the Milan base and are expected to be up and 220 Zellers leases. pared-down business, Baker noted. “We are running within the first half. Target’s entry into Canada marks the going to run all Zellers stores through 2011, The company said the openings are in line with international develop- chain’s first expansion outside the U.S. The then run many in 2012. By 2013, it will be a ment of its brands and will help it approach creativity in a new manner. deal may also open the way for other retailers small division,” he said. -

Procter & Gamble Baltimore Plant

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 (Rev. 10-90) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM This foJ:lll is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for inda.:vidual properties and d ist=Yicts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Rlttjistration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete ea~h item by marking "x" in tlie appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If any item does not apply t~the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable . " For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all items. ==============================~============================================ 1. Name of Property ==================== ======================================================= historic name Procter & Gamble Baltimore Plant other names/site number ..-.B~-~1-0~0~9--~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ =========================================================================== 2. Location =========================================================================== street 1422 Nicholson Street not for publication n.L.a. city or town -=B~a~l~t~i~·m~o""-=-r~e,__~~~~~ vicinity n/a state Maryland code MD county independent city code 21.Q zip code 21617 =========================================================================== -

Historic Resources Study of Pullman National Monument, Illinois

Michigan Technological University Digital Commons @ Michigan Tech Michigan Tech Publications 12-2019 Historic Resources Study of Pullman National Monument, Illinois Laura Walikainen Rouleau Michigan Technological University, [email protected] Sarah Fayen Scarlett Michigan Technological University, [email protected] Steven A. Walton Michigan Technological University, [email protected] Timothy Scarlett Michigan Technological University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.mtu.edu/michigantech-p Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons, Other Anthropology Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Walikainen Rouleau, L., Scarlett, S. F., Walton, S. A., & Scarlett, T. (2019). Historic Resources Study of Pullman National Monument, Illinois. Report for the National Park Service. Retrieved from: https://digitalcommons.mtu.edu/michigantech-p/14692 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.mtu.edu/michigantech-p Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons, Other Anthropology Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the United States History Commons National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Midwest Archeological Center Lincoln, Nebraska Historic Resource Survey PULLMAN NATIONAL HISTORICAL MONUMENT Town of Pullman, Chicago, Illinois Dr. Laura Walikainen Rouleau Dr. Sarah Fayen Scarlett Dr. Steven A. Walton and Dr. Timothy J. Scarlett Michigan Technological University 31 December 2019 HISTORIC RESOURCE STUDY OF PULLMAN NATIONAL MONUMENT, Illinois Dr. Laura Walikainen Rouleau Dr. Sarah Fayen Scarlett Dr. Steven A. Walton and Dr. Timothy J. Scarlett Department of Social Sciences Michigan Technological University Houghton, MI 49931 Submitted to: Dr. Timothy M. Schilling Midwest Archeological Center, National Park Service 100 Centennial Mall North, Room 44 7 Lincoln, NE 68508 31 December 2019 Historic Resource Study of Pullman National Monument, Illinois by Laura Walikinen Rouleau Sarah F. -

Your Retirement Benefits

Your Retirement Benefits The Procter & Gamble Profit Sharing Trust and Employee Stock Ownership Plan Plan Information Summary Plan Description and Prospectus This document constitutes part of a prospectus covering securities that have been registered under the Securities Act of 1933 and should be retained for future reference. The Profit Sharing Trust and Employee Stock Ownership Plan is governed by official Plan documents, which are always the final authority on the Plan. July 1, 2007 Summary Plan Description and Prospectus 2012 Procter & Gamble, All Rights Reserved Publication Date: 05/31/2012 Introduction P&G originated on the banks of the Ohio River in Cincinnati, Ohio, when two brothers-in-law merged their specialties into a partnership. William Procter was a candle maker, and James Gamble was a soap maker. The idea of sharing the Company’s profits with employees was introduced by a grandson of one of the founders, William Cooper Procter. Cooper, as he was known, had begun his training by working in the factory. Creating an Incentive for Workers After listening to the workers, he wanted to find a way to instill in employees the same desire to succeed as a person who owned their own business. “We should let the employees share in the firm’s earnings,” he said. “That will give them an incentive to increase earnings.” Cooper Procter introduced the idea of profit sharing to the U.S. in 1887. Each employee received a cash payment from the profits of the Company based upon a formula that also considered length of service. The payments were made at a Company picnic on a day known as “Dividend Day” (a day that many locations in the U.S. -

The Procter & Gamble Company Address

The Procter & Gamble Company Address: One Procter & Gamble Plaza Cincinnati, Ohio 45202-3315 U.S.A. Telephone: (513) 983-1100 Fax: (513) 983-9369 http://www.pg.com/ Statistics: Public Company Incorporated: 1890 Employees: 110,000 Sales: $51.41 billion (2004) Stock Exchanges: New York National (NSX) Amsterdam Paris Basel Geneva Lausanne Z� rich Frankfurt Brussels Ticker Symbol: PG NAIC: 311111 Dog and Cat Food Manufacturing; 311919 Other Snack Food Manufacturing; 311920 Coffee and Tea Manufacturing; 322291 Sanitary Paper Product Manufacturing; 325412 Pharmaceutical Preparation Manufacturing; 325611 Soap and Other Detergent Manufacturing; 325612 Polish and Other Sanitation Good Manufacturing; 325620 Toilet Preparation Manufacturing; 339994 Broom, Brush, and Mop Manufacturing Company Perspectives: We will provide branded products and services of superior quality and value that improve the lives of the world's consumers. As a result, consumers will reward us with leadership sales, profit, and value creation, allowing our people, our shareholders, and the communities in which we live and work to prosper. Key Dates: 1837: William Procter and James Gamble form Procter & Gamble, a partnership in Cincinnati, Ohio, to manufacture and sell candles and soap. c. 1851: Company's famous moon-and-stars symbol is created. 1878: P&G introduces White Soap, soon renamed Ivory. 1890: The Procter & Gamble Company is incorporated. 1911: Crisco, the first all-vegetable shortening, debuts. 1931: Brand management system is formally introduced. 1946: P&G introduces Tide laundry detergent. 1955: Crest toothpaste makes its debut. 1957: Charmin Paper Company is acquired. 1961: Test marketing of Pampers disposable diapers begins. 1963: Company acquires the Folgers coffee brand. -

2002 Sustainability Report Linking Opportunity with Responsibility

2002 Sustainability Report Linking Opportunity with Responsibility P&G 2002 Sustainability Report 1 Sustainable development is a very simple idea. It is about ensuring a better quality of life for everyone, now and for generations to come. P&G’s Statement of Purpose We will provide products and services of superior quality and value that improve the lives of the world’s consumers. As a result, consumers will reward us with leadership sales, profit and value creation, allowing our people, our shareholders, and the communities in which we live and work to prosper. Table of Contents A. G. Lafley’s Statement 2 Vision 3 Executive Summary 4 P&G Profile 7 Policies, Organization, & Management Systems 14 Performance 36 Environmental 38 This report was prepared using the Global Reporting Initiative’s Economic 46 (GRI) June 2000 Sustainability Reporting Guidelines. The mission Social 49 of the GRI is to promote international harmonization in the Sustainability In Action 51 reporting of relevant and credible corporate economic, environmental, and social performance information to enhance responsible decision making. The GRI pursues this mission through a multistakeholder process of open dialogue and collaboration in the design and implementation of widely applicable sustainability reporting guidelines. The GRI has not verified the contents of this report, nor does it take a position on the reliability of information reported herein. For further information about the GRI, please visit on the Web www.globalreporting.org The GRI’s Sustainability Reporting Guidelines were released in exposure draft form in London in March 1999. The GRI Guidelines represent the first global framework for comprehensive sustainability reporting, encompassing the “triple bottom line” of economic, environmental, and social issues. -

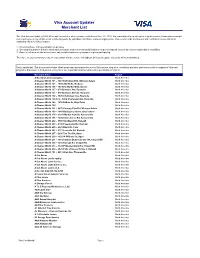

Visa Account Updater Merchant List

Visa Account Updater Merchant List The Visa Account Updater (VAU) Merchant List includes all merchants enrolled as of June 30, 2020. It is consolidated in an attempt to relay the most relevant and meaningful merchant name as merchants enroll at differing levels: by subsidiary, franchise, or parent organization. Visa recommends that issuers and merchants not use this list in marketing efforts for VAU because: 1. We do not have 100% penetration on all sides. 2. We cannot guarantee that the information exchange between the financial institution and merchant will occur in time for the cardholder’s next billing. 3. Some merchants on this list may have only certain divisions or geographic regions participating. Therefore, we do not want to create an expectation that the service will address all account update issues for all merchants listed. Visa Confidential: This document contains Visa's proprietary information for use by Visa issuers, acquirers, merchants and their processors solely in support of Visa card programs. Disclosure to third parties or any other use is prohibited without prior written permission of Visa Inc. Merchant Name Region A Buckley Landscaping Inc. North America A Cleaner World 106 – 3481 Robinhood Rd, Winston-Salem North America A Cleaner World 107 – 1009 2Nd St Ne, Hickory North America A Cleaner World 108 – 130 New Market Blvd, Boone North America A Cleaner World 127 – 679 Brandon Ave, Roanoke North America A Cleaner World 127 – 679 Brandon Avenue, Roanoke North America A Cleaner World 128 – 3806 Challenger Ave, Roanoke