Proceedings-Symposium on Whitebark Pine Ecosystems

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Table of Contents

Appendix C Botanical Resources Table of Contents Purpose Of This Appendix ............................................................................................................. Below Tables C-1. Federal and State Status, Current and Proposed Forest Service Status, and Global Distribution of the TEPCS Plant Species on the Sawtooth National Forest ........................... C-1 C-2. Habit, Lifeform, Population Trend, and Habitat Grouping of the TEPCS Plant Species for the Sawtooth National Forest ............................................................................... C-3 C-3. Rare Communities, Federal and State Status, Rarity Class, Threats, Trends, and Research Natural Area Distribution for the Sawtooth National Forest ................................... C-5 C-4. Plant Species of Cultural Importance for the Sawtooth National Forest ................................... C-6 PURPOSE OF THIS APPENDIX This appendix is designed to provide detailed information about habitat, lifeform, status, distribution, and habitat grouping for the Threatened, Proposed, Candidate, and Sensitive (current and proposed) plant species found on the Sawtooth National Forest. The detailed information is provided to enable managers to more efficiently direct the implementation of Botanical Resources goals, objectives, standards, and guidelines. Additionally, this appendix provides detailed information about the rare plant communities located on the Sawtooth National Forest and should provide additional support of Forest-wide objectives. Species of cultural -

Representativeness Assessment of Research Natural Areas on National Forest System Lands in Idaho

USDA United States Department of Representativeness Assessment of Agriculture Forest Service Research Natural Areas on Rocky Mountain Research Station National Forest System Lands General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-45 in Idaho March 2000 Steven K. Rust Abstract Rust, Steven K. 2000. Representativeness assessment of research natural areas on National Forest System lands in Idaho. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-45. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 129 p. A representativeness assessment of National Forest System (N FS) Research Natural Areas in ldaho summarizes information on the status of the natural area network and priorities for identification of new Research Natural Areas. Natural distribution and abundance of plant associations is compared to the representation of plant associations within natural areas. Natural distribution and abundance is estimated using modeled potential natural vegetation, published classification and inventory data, and Heritage plant community element occur- rence data. Minimum criteria are applied to select only viable, high quality plant association occurrences. In assigning natural area selection priorities, decision rules are applied to encompass consideration of the adequacy and viability of representation. Selected for analysis were 1,024 plant association occurrences within 21 4 natural areas (including 115 NFS Research Natural Areas). Of the 1,566 combinations of association within ecological sections, 28 percent require additional data for further analysis; 8, 40, and 12 percent, respectively, are ranked from high to low conservation priority; 13 percent are fully represented. Patterns in natural area needs vary between ecological section. The result provides an operational prioritization of Research Natural Area needs at landscape and subregional scales. -

Appendix a List of Preparers and Reviewers

Glossary adfluvial —Referring to fish that live in lakes and no significant impact, aids an agency’s compliance migrate to rivers and streams. with the National Environmental Policy Act when Beyond the Boundaries —National Wildlife Refuge no environmental impact statement is necessary, Association program to expand conservation work and facilitates preparation of a statement when to areas outside national wildlife refuge borders. one is necessary. BRWCA —Bear River Watershed Conservation Area. fluvial —Referring to fish that live in rivers and candidate species —A species of plant or animal for streams. which the USFWS has sufficient information on GCN —(A species of) greatest conservation need. their biological status and threats to propose them HAPET —Habitat and Population Evaluation Team. as endangered or threatened under the Endan- Important Bird Areas Program —A global effort to gered Species Act, but for which development of find and conserve areas that are vital to birds a proposed listing regulation is precluded by other and other biodiversity sponsored by the National higher priority listing activities. Audubon Society. CFR —Code of Federal Regulations. Intermountain West Joint Venture —Diverse partner- CO2 —Carbon dioxide. ship of 18 entities including Federal agencies, conservation easement —A legally enforceable State agencies, nonprofit conservation organiza- encumbrance or transfer of property rights to a tions, and for-profit organizations representing government agency or land trust for the purposes agriculture and industry. IWJV was founded in of conservation. Rights transferred could include 1994 to facilitate bird conservation across the vast the discretion to subdivide or develop land, change 495 million acres of the Intermountain West. -

Conservation Strategy for Spokane River Basin Wetlands

CONSERVATION STRATEGY FOR SPOKANE RIVER BASIN WETLANDS Prepared by Mabel Jankovsky-Jones Conservation Data Center June 1999 Idaho Department of Fish and Game Natural Resource Policy Bureau 600 South Walnut, P.O. Box 25 Boise, ID 83707 Jerry Mallet, Interim Director Report prepared with funding from the United States Environmental Protection Agency through Section 104(b) (3) of the Clean Water Act Grant No. CD990620-01-0 SUMMARY The Idaho Conservation Data Center has received wetland protection grant funding from the Environmental Protection Agency under the authority of Section 104 (b)(3) of the Clean Water Act to enhance existing wetland information systems. The information summarized here can be applied to state biodiversity, conservation, and water quality enhancement projects on a watershed basis. Previous project areas included the Henrys Fork Basin, Big Wood River Basin, southeastern Idaho watersheds, the Idaho Panhandle, and east-central basins. This document is a summary of information compiled for the Spokane River Basin. We used the United States Fish and Wildlife Service National Wetlands Inventory (NWI) to gain a broad perspective on the areal extant and types of wetlands in the survey area. Land ownership and management layers were overlaid on the NWI to determine ownership and the protected status of wetlands. Plant communities occurring in the survey area were placed into the hierarchical NWI classification and provide information relative to on-the-ground resource management. Assessment of the quality and condition of plant communities and the occurrence of rare plant and animal species allowed us to categorize twenty-four wetland sites based on conservation intent. -

The Genus Vaccinium in North America

Agriculture Canada The Genus Vaccinium 630 . 4 C212 P 1828 North America 1988 c.2 Agriculture aid Agri-Food Canada/ ^ Agnculturo ^^In^iikQ Canada V ^njaian Agriculture Library Brbliotheque Canadienno de taricakun otur #<4*4 /EWHE D* V /^ AgricultureandAgri-FoodCanada/ '%' Agrrtur^'AgrntataireCanada ^M'an *> Agriculture Library v^^pttawa, Ontano K1A 0C5 ^- ^^f ^ ^OlfWNE D£ W| The Genus Vaccinium in North America S.P.VanderKloet Biology Department Acadia University Wolfville, Nova Scotia Research Branch Agriculture Canada Publication 1828 1988 'Minister of Suppl) andS Canada ivhh .\\ ailabla in Canada through Authorized Hook nta ami other books! or by mail from Canadian Government Publishing Centre Supply and Services Canada Ottawa, Canada K1A0S9 Catalogue No.: A43-1828/1988E ISBN: 0-660-13037-8 Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data VanderKloet,S. P. The genus Vaccinium in North America (Publication / Research Branch, Agriculture Canada; 1828) Bibliography: Cat. No.: A43-1828/1988E ISBN: 0-660-13037-8 I. Vaccinium — North America. 2. Vaccinium — North America — Classification. I. Title. II. Canada. Agriculture Canada. Research Branch. III. Series: Publication (Canada. Agriculture Canada). English ; 1828. QK495.E68V3 1988 583'.62 C88-099206-9 Cover illustration Vaccinium oualifolium Smith; watercolor by Lesley R. Bohm. Contract Editor Molly Wolf Staff Editors Sharon Rudnitski Frances Smith ForC.M.Rae Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada - Agriculture et Agroalimentaire Canada http://www.archive.org/details/genusvacciniuminOOvand -

Proceedings, Western Section, American Society of Animal Science

Proceedings, Western Section, American Society of Animal Science Vol. 54, 2003 INFLUENCE OF PREVIOUS CATTLE AND ELK GRAZING ON THE SUBSEQUENT QUALITY AND QUANTITY OF DIETS FOR CATTLE, DEER, AND ELK GRAZING LATE-SUMMER MIXED-CONIFER RANGELANDS D. Damiran1, T. DelCurto1, S. L. Findholt2, G. D. Pulsipher1, B. K. Johnson2 1Eastern Oregon Agricultural Research Center, OSU, Union 97883; 2Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, La Grande 97850 ABSTRACT: A study was conducted to determine consequences on the following seasons forage resources. foraging efficiency of cattle, mule deer, and elk in response Coe et al. (2001) concluded competition for forage could to previous grazing by elk and cattle. Four enclosures, in occur between elk and cattle in late summer and species previously logged mixed conifer (Abies grandis) rangelands interactions may be stronger between elk and cattle than were chosen, and within each enclosure, three 0.75 ha deer and cattle. Furthermore, the response of elk and/or pastures were either: 1) ungrazed, 2) grazed by cattle, or 3) deer to cattle grazing may vary seasonally depending on grazed by elk in mid-June and mid-July to remove forage availability and quality (Peek and Krausman, 1996; approximately 40% of total forage yield. After grazing Wisdom and Thomas, 1996). In the fall, winter, and spring, treatments, each pasture was subdivided into three 0.25 ha elk preferred to forage where cattle had lightly or sub-pastures and 16 (4 animals and 4 bouts/animal) 20 min moderately grazed the preceding summer (Crane et al., grazing trials were conducted in each sub-pasture using four 2001). -

Draft Plant Propagation Protocol

Vaccinium scoparium Leib. ex Coville - Plant Propagation Protocol ESRM 412 – Native Plant Production TAXONOMY Family Names Family Scientific Name: Ericaceae Family Common Name: Heath Family Scientific Names Genus: Vaccinium Species: scoparium Species Authority: Leib. ex Coville Variety: Sub-species: Cultivar: Authority for Variety/Sub-species: Common Synonym Genus: Species: Species Authority: Variety: Sub-species: Cultivar: Authority for Variety/Sub-species: Common Names: Grouse Whortleberry, grouse huckleberry, littleleaf huckleberry, whortleberry, red huckleberry Species Code (as per USDA Plants VASC database): GENERAL INFORMATION General Distribution: British Columbia to Northern California, Idaho to Alberta, South Dakota through the Rockies to Colorado, generally at higher elevations.i Climate and elevation range: Found in the Pacific Northwest from 700-2300 meters and in Colorado from 2600-3800 meters.ii Local habitat and abundance; may Growing on rocky subalpine to alpine woods and include commonly associated slopes, V. scoparium is found in acidic soils on moist species and dry sites, though more commonly on well drained sites and especially in association with lodgepole pine (P. contorta).iii Plant strategy type: Vaccinium are poor competitors, often struggling with perennial weeds. While common in fire adapted eastside ecosystems, burned plants can take 10-15 years to recover.iv PROPAGATION DETAILS Ecotype: Propagation Goal: Plants Propagation Method: Seed (note vegetative method available at http://www.nativeplantnetwork.org)v -

F. Key to Abies Lasiocarpa Habitat Types

F. Key to Abies lasiocarpa habitat types 1. Equisetum arvense abundant PICEA ENGELMANNII/EQUISETUN ARVENSE h.t. (p.36) 1. E. arvense not abundant 2 2. Caltha leptosepala common or Trollius laxus well represented PICEA ENGELMANNII/CALTHA LEPTOSEPALA h.t. (p.37) 2. ~. leptosepala scarce and!. laxus poorly represented 3 3. Carex disperma well represented PICEA ENGELMANNII/CAREX DISPERMA h.t. (p.38) 3. ~. disperma poorly represented. 4 4. Calamagrostis canadensis or Ledum glandulosum well represented ABIES LASIOCARPA/CALAMAGROSTIS CANADENSIS h.t. (p.4S) 4a. Ledum glandulosum well represented LEDUM GLANDULOSUM phase* (p.4S) 4b. Not as above; Vaccinium caespitosum common VACCINIUM CAESPITOSUM phase* (p.4S) 4c. Not as above in 4a or 4b CALAMAGROSTIS CANADENSIS phase (p.4S) 4. C. canadensis and L. glandulosum poorly represented 5 5. Streptopus amplexifolius or Senecio triangularis well represented either separately or collectively ABIES LASIOCARPA/STREPTOPUS AMPLEXIFOLIUS h. t.* (p.46) 5. Not as above 6 6. Menziesia ferruginea well represented ABIES LASIOCARPA/MENZIESIA FERRUGINEA h.t.* (p.47) 6. ~. ferruginea poorly represented 7 7. Actaea rubra common ABIES LASIOCARPA/ACTAEA RUBRA h.t. (p.47) 7. A. rubra scarce 8 8. Physocarpus malvaceus well represented ABIES LASIOCARPA/PHYSOCARPUS ~1ALVACEUS h.t. (p.48) 8. ~. malvaceus poorly represented 9 9. Acer glabrum or Sorbus scopulina well represented either separately or collectively ABIES LASIOCARPA/ACER GLABRUM h.t. (p.48) 9. Not as above . 10 10. Linnaea borealis common ABIES LASIOCARPA/LINNAEA BOREALIS h.t. (p.49) lOa. Vaccinium scoparium well represented VACCINIUM SCOPARIl~ phase (p.49) lOb. ~. scoparium poorly represented LINNAEA BOREALIS phase (p.49) 10. -

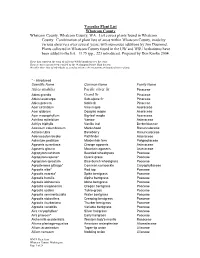

Vascular Plant List Whatcom County Whatcom County. Whatcom County, WA

Vascular Plant List Whatcom County Whatcom County. Whatcom County, WA. List covers plants found in Whatcom County. Combination of plant lists of areas within Whatcom County, made by various observers over several years, with numerous additions by Jim Duemmel. Plants collected in Whatcom County found in the UW and WSU herbariums have been added to the list. 1175 spp., 223 introduced. Prepared by Don Knoke 2004. These lists represent the work of different WNPS members over the years. Their accuracy has not been verified by the Washington Native Plant Society. We offer these lists to individuals as a tool to enhance the enjoyment and study of native plants. * - Introduced Scientific Name Common Name Family Name Abies amabilis Pacific silver fir Pinaceae Abies grandis Grand fir Pinaceae Abies lasiocarpa Sub-alpine fir Pinaceae Abies procera Noble fir Pinaceae Acer circinatum Vine maple Aceraceae Acer glabrum Douglas maple Aceraceae Acer macrophyllum Big-leaf maple Aceraceae Achillea millefolium Yarrow Asteraceae Achlys triphylla Vanilla leaf Berberidaceae Aconitum columbianum Monkshood Ranunculaceae Actaea rubra Baneberry Ranunculaceae Adenocaulon bicolor Pathfinder Asteraceae Adiantum pedatum Maidenhair fern Polypodiaceae Agoseris aurantiaca Orange agoseris Asteraceae Agoseris glauca Mountain agoseris Asteraceae Agropyron caninum Bearded wheatgrass Poaceae Agropyron repens* Quack grass Poaceae Agropyron spicatum Blue-bunch wheatgrass Poaceae Agrostemma githago* Common corncockle Caryophyllaceae Agrostis alba* Red top Poaceae Agrostis exarata* -

Foods Eaten by the Rocky Mountain

were reported as trace amounts were excluded. Factors such as relative plant abundance in relation to consumption were considered in assigning plants to use categories when such information was Foods Eaten by the available. An average ranking for each species was then determined on the basis Rocky Mountain Elk of all studies where it was found to contribute at least 1% of the diet. The following terminology is used throughout this report. Highly valuable plant-one avidly sought by elk and ROLAND C. KUFELD which made up a major part of the diet in food habits studies where encountered, or Highlight: Forty-eight food habits studies were combined to determine what plants which was consumed far in excess of its are normally eaten by Rocky Mountain elk (Cervus canadensis nelsoni), and the rela- vegetative composition. These had an tive value of these plants from a manager’s viewpoint based on the response elk have average ranking of 2.25 to 3.00. Valuable exhibited toward them. Plant species are classified as highly valuable, valuable, or least plants-one sought and readily eaten but valuable on the basis of their contribution to the diet in food habits studies where to a lesser extent than highly valuable they were recorded. A total of 159 forbs, 59 grasses, and 95 shrubs are listed as elk plants. Such plants made up a moderate forage and categorized according to relative value. part of the diet in food habits studies where encountered. Valuable plants had an average ranking of 1.50 to 2.24. Least Knowledge of the relative forage value elk food habits, and studies meeting the valuable plant-one eaten by elk but which of plants eaten by elk is basic to elk range following criteria were incorporated: (1) usually made up a minor part of the diet surveys, and to planning and evaluation Data must be original and derived from a in studies where encountered, or which of habitat improvement programs. -

Flora, Chorology, Biomass and Productivity of the Pinus Albicaulis

Flora, chorology, biomass and productivity of the Pinus albicaulis-Vaccinium scoparium association by Frank Forcella A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in BOTANY Montana State University © Copyright by Frank Forcella (1977) Abstract: The Pinus dlbieaulis - Vacoinium seoparium association is restricted to noncalcareous sites in the subalpine zone of the northern Rocky Mountains (USA). The flora of the association changes clinally with latitude. Stands of this association may annually produce a total (above- and belowground) of 950 grams of dry matter per square meter and may obtain biomasses of nearly 60 kg per square meter. General productivity and biomass may be accurately estimated from simple measurements of stand basal area and median shrub coverage for the tree and shrub synusiae respectively. Mean cone and seed productivities range up to 84 and 25 grams per square meter per year respectively, and these productivities are correlated with percent canopy coverage (another easily measured stand parameter). Edible food production of typical stands of this association is sufficient to support 1000 red squirrels, 20 black bears or 50 humans on a square km basis. The spatial and temporal fluctuations of Pinus albicaulis seed production suggests that strategies for seed predator avoidance may have been selected for in this taxon. STATEMENT OF PERMISSION TO COPY In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the're quirements for an advanced degree at Montana State University, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for inspec tion. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by my major pro fessor, or in his absence, by the Director of Libraries. -

Proceedings-Symposium on Whitebark Pine Ecosystems

Whitebark pine community types and their patterns on the landscape Authors: Stephen F. Arno and Tad Weaver This is a published article that originally appeared in Proceedings - Symposium on whitebark pine ecosystems: ecology and management of a high mountain resource, USDA Forest Service General Tech Report INT-270 in 1990. The final version can be found at https://doi.org/10.2737/ INT-GTR-270. S Arno and T Weaver 1990. Whitebark pine community types and their patterns on the landscape. p97-105. Schmidt, Wyman C.; McDonald, Kathy J., compilers. 1990. Proceedings - Symposium on whitebark pine ecosystems: Ecology and management of a high-mountain resource; 1989 March 29-31; Bozeman, MT. Gen. Tech. Rep. INT-GTR-270. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Research Station. 386 p. Made available through Montana State University’s ScholarWorks scholarworks.montana.edu WHITEBARK PINE COMMUNITY TYPES AND THEIR PATTERNS ON THE LANDSCAPE Stephen F. Arno Tad Weaver ABSTRACT INTRODUCTION Within whitebark pine's (Pinus albicaulis) relatively Whitebark pine (Pinus albicaulis) is a prominent spe narrow zone ofoccurrence-the highest elevations of tree cies in the upper subalpine forest and timberline zones on growth from California and Wyoming north to British high mountains of western North America. Here, a great Columbia and Alberta-this species is a member ofdiverse variety of tree-dominated and nonarboreal communities plant communities. This paper summarizes studies from form a complex vegetational mosaic on the rugged land throughout its distribution that have described community scape. While few studies have provided detailed descrip types containing whitebark pine and the habitat types tions of these communities or the causes of their distribu (environmental types based on potential vegetation) it tional patterns, it is possible to list the major community occupies.