Fergus, Galloway and the Scots

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Safap October2016 Minutes Final

Minutes of the meeting of THE SCOTTISH ARCHAEOLOGICAL FINDS ALLOCATION PANEL 10:45am, Thursday 27th October 2016 Present: Dr Evelyn Silber (Chair), Neil Curtis, Dr Murray Cook (via Skype), Jilly Burns (NMS), Paul MacDonald, Richard Welander (HES), Mary McLeod Rivett In attendance: Stuart Campbell (TTU), Dr Natasha Ferguson (TTU), Andrew Brown (QLTR Solicitor). Dr Natasha Ferguson took the minutes 1. Apologies Apologies from Jacob O’Sullivan (MGS). 2. Chair Remarks The Chair informed the panel that the QLTR had received a response from SG to a letter highlighting issues relating to increasing numbers of disclaimed cases. It was agreed the points would be discussed further at the Annual Review Meeting on 14th November. The panel agreed to form a sub-committee (of NC, JB, RW & AB) to deal with revisions of the Code of Practice in relation to multiple applications. The next date of the panel meeting confirmed as Thursday 23rd March 2017. Further dates in 2017 to be proposed. It is proposed that the number of meetings is reduced to three by combining the Annual Review meeting with a panel meeting. This will be discussed at the next Annual Review meeting on 14th November 2016. 3. Discussion of Galloway Hoard, valuations and timescales JB (NMS) was absent from this discussion. The panel were updated on the current status of the Galloway Hoard, including projected timescales for allocation. The panel also discussed the criteria for assessing the valuations. The 31st January 2017 was agreed as a proposed date to hold an extraordinary SAFAP meeting in relation to allocating the Galloway Hoard. -

Camping Pocket Guide

CONTENTS Get Ready for Camping 04 Add To Your Experience 07 Enjoy Family Picnics 08 Scenic Scotland 10 Visit National Parks 14 Amazing Wildlife 16 GET READY FOR CAMPING - Stargazing - Experience the freedom of a touring trip, where you can Sleeping under the stars is the perfect opportunity to wake up in a different part of the country every day. Or get familiar with the wonders of the sky at night. Plan enjoy a bit of luxury at a holiday park and spend a restful a camping trip to the Glentrool Camping and Caravan week in the comfy surrounds of a state-of-the-art static Site in the Galloway Forest Park, the UK’s first Dark Sky caravan, or pack in some fun activities with the kids. Park, or sail to Scotland’s first Dark Sky island. There’s There’s a camping and caravanning holiday in Scotland minimum light pollution on the Isle of Coll, where the to suit every preference and budget. nearest lamppost is 20 miles away! Start planning a break today and find your perfect Experience more stargazing opportunities and discover camping or caravanning destination. Scotland’s inky black skies on our website. - Stunning views - - Campsites near castles - Summer is the time to be spontaneous – pack the tent Why not combine your camping or caravanning trip into the car, head out onto the open road, and pitch up in with a bit of history and book a pitch in the grounds of a some beautiful locations. You’ll find campsites set below castle? You’ll find such camping grounds in many parts breathtaking mountain ranges, overlooking pristine of the country, from the impressive 18th century Culzean beaches, or in the middle of lush, open countryside. -

Archaeological Excavations at Castle Sween, Knapdale, Argyll & Bute, 1989-90

Proc Soc Antiq Scot, (1996)6 12 , 517-557 Archaeological excavation t Castlsa e Sween, Knapdale, Argyll & Bute, 1989-90 Gordon Ewart Triscottn Jo *& t with contributions by N M McQ Holmes, D Caldwell, H Stewart, F McCormick, T Holden & C Mills ABSTRACT Excavations Castleat Sween, Argyllin Bute,& have thrown castle of the history use lightthe on and from construction,s it presente 7200c th o t , day. forge A kilnsd evidencee an ar of industrial activity prior 1650.to Evidence rangesfor of buildings within courtyardthe amplifies previous descriptions castle. ofthe excavations The were funded Historicby Scotland (formerly SDD-HBM) alsowho supplied granta towards publicationthe costs. INTRODUCTION Castle Sween, a ruin in the care of Historic Scotland, stands on a low hill overlooking an inlet, Loch Sween, on the west side of Knapdale (NGR: NR 712 788, illus 1-3). Its history and architectural development have recently been reviewed thoroughl RCAHMe th y b y S (1992, 245-59) castle Th . e s theri e demonstrate havo dt e five major building phases datin c 1200 o earle gt th , y 13th century, c 1300 15te th ,h century 16th-17te th d an , h centur core y (illueTh . wor 120c 3) s f ko 0 consista f so small quadrilateral enclosure castle. A rectangular wing was added to its west face in the early 13th century. This win s rebuilgwa t abou t circulaa 1300 d an , r tower with latrinee grounth n o sd floor north-ease th o buils t n wa o t t enclosurcornee th 15te f o rth hn i ecentury l thesAl . -

THE MYTHOLOGY, TRADITIONS and HISTORY of Macdhubhsith

THE MYTHOLOGY, TRADITIONS and HISTORY OF MacDHUBHSITH ― MacDUFFIE CLAN (McAfie, McDuffie, MacFie, MacPhee, Duffy, etc.) VOLUME 2 THE LANDS OF OUR FATHERS PART 2 Earle Douglas MacPhee (1894 - 1982) M.M., M.A., M.Educ., LL.D., D.U.C., D.C.L. Emeritus Dean University of British Columbia This 2009 electronic edition Volume 2 is a scan of the 1975 Volume VII. Dr. MacPhee created Volume VII when he added supplemental data and errata to the original 1792 Volume II. This electronic edition has been amended for the errata noted by Dr. MacPhee. - i - THE LIVES OF OUR FATHERS PREFACE TO VOLUME II In Volume I the author has established the surnames of most of our Clan and has proposed the sources of the peculiar name by which our Gaelic compatriots defined us. In this examination we have examined alternate progenitors of the family. Any reader of Scottish history realizes that Highlanders like to move and like to set up small groups of people in which they can become heads of families or chieftains. This was true in Colonsay and there were almost a dozen areas in Scotland where the clansman and his children regard one of these as 'home'. The writer has tried to define the nature of these homes, and to study their growth. It will take some years to organize comparative material and we have indicated in Chapter III the areas which should require research. In Chapter IV the writer has prepared a list of possible chiefs of the clan over a thousand years. The books on our Clan give very little information on these chiefs but the writer has recorded some probable comments on his chiefship. -

Consultation on Proposals to Reform Fatal Accident Inquiries Legislation

CONSULTATION ON PROPOSALS TO REFORM FATAL ACCIDENT INQUIRIES LEGISLATION RESPONDENT INFORMATION FORM Please Note this form must be returned with your response to ensure that we handle your response appropriately. This consultation closes on Tuesday 9 September 2014. 1. Name/Organisation Organisation Name West Lothian Council Title Mr Ms Mrs Miss Dr Please tick as appropriate Surname Forename 2. Postal Address Legal Services West Lothian Council, West Lothian Civic Centre Howden South Road Livingston Postcode EH54 6FF Phone Email 3. Permissions - I am responding as… Individual / Group/Organisation Please tick as appropriate x (a) Do you agree to your response being made (c) The name and address of your organisation available to the public (in Scottish will be made available to the public (in the Government library and/or on the Scottish Scottish Government library and/or on the Government web site)? Scottish Government web site). Please tick as appropriate Yes No (b) Where confidentiality is not requested, we will Are you content for your response to be make your responses available to the public made available? on the following basis Please tick ONE of the following boxes Please tick as appropriate X Yes No Yes, make my response, name and address all available or Yes, make my response available, but not my name and address or Yes, make my response and name available, but not my address (d) We will share your response internally with other Scottish Government policy teams who may be addressing the issues you discuss. They may wish to contact you again in the future, but we require your permission to do so. -

Tillicoultry Estate and the Influence of The

WHO WAS LADY ANNE? A study of the ownership of the Tillicoultry Estate, Clackmannanshire, and the role and influence of the Wardlaw Ramsay Family By Elizabeth Passe Written July 2011 Edited for the Ochils Landscape Partnership, January 2013 Page 1 of 24 CONTENTS Page 2 Contents Page 3 Acknowledgements, introduction, literature review Page 5 Ownership of the estate Page 7 The owners of Tillicoultry House and Estate and their wives Page 10 The owners in the 19th century - Robert Wardlaw - Robert Balfour Wardlaw Ramsay - Robert George Wardlaw Ramsay - Arthur Balcarres Wardlaw Ramsay Page 15 Tenants of Tillicoultry House - Andrew Wauchope - Alexander Mitchell - Daniel Gardner Page 17 Conclusion Page 18 Nomenclature and bibliography Page 21 Appendix: map history showing the estate Figures: Page 5 Fig. 1 Lady Ann’s Wood Page 6 Fig. 2 Ordnance Survey map 1:25000 showing Lady Ann Wood and well marked with a W. Page 12 Fig. 3 Tillicoultry House built in the early 1800s Page 2 of 24 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My grateful thanks are due to: • Margaret Cunningham, my course tutor at the University of Strathclyde, for advice and support • The staff of Clackmannanshire Libraries • Susan Mills, Clackmannanshire Museum and Heritage Officer, for a very useful telephone conversation about Tillicoultry House in the 1930s • Elma Lindsay, a course survivor, for weekly doses of morale boosting INTRODUCTION Who was Lady Anne? This project was originally undertaken to fulfil the requirements for the final project of the University of Strathclyde’s Post-graduate Certificate in Family History and Genealogy in July 2011. My interest in the subject was sparked by living in Lady Anne Grove for many years and by walking in Lady Anne’s Wood and to Lady Anne’s Well near the Kirk Burn at the east end of Tillicoultry. -

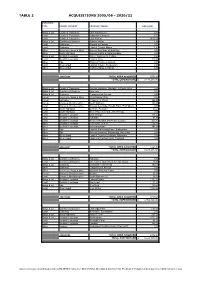

Table 2-Acquisitions (Web Version).Xlsx TABLE 2 ACQUISITIONS 2005/06 - 2020/21

TABLE 2 ACQUISITIONS 2005/06 - 2020/21 PURCHASE TYPE FOREST DISTRICT PROPERTY NAME AREA (HA) Bldgs & Ld Cowal & Trossachs Edra Farmhouse 2.30 Land Cowal & Trossachs Ardgartan Campsite 6.75 Land Cowal & Trossachs Loch Katrine 9613.00 Bldgs & Ld Dumfries & Borders Jufrake House 4.86 Land Galloway Ground at Corwar 0.70 Land Galloway Land at Corwar Mains 2.49 Other Inverness, Ross & Skye Access Servitude at Boblainy 0.00 Other North Highland Access Rights at Strathrusdale 0.00 Bldgs & Ld Scottish Lowlands 3 Keir, Gardener's Cottage 0.26 Land Scottish Lowlands Land at Croy 122.00 Other Tay Rannoch School, Kinloch 0.00 Land West Argyll Land at Killean, By Inverary 0.00 Other West Argyll Visibility Splay at Killean 0.00 2005/2006 TOTAL AREA ACQUIRED 9752.36 TOTAL EXPENDITURE £ 3,143,260.00 Bldgs & Ld Cowal & Trossachs Access Variation, Ormidale & South Otter 0.00 Bldgs & Ld Dumfries & Borders 4 Eshiels 0.18 Bldgs & Ld Galloway Craigencolon Access 0.00 Forest Inverness, Ross & Skye 1 Highlander Way 0.27 Forest Lochaber Chapman's Wood 164.60 Forest Moray & Aberdeenshire South Balnoon 130.00 Land Moray & Aberdeenshire Access Servitude, Raefin Farm, Fochabers 0.00 Land North Highland Auchow, Rumster 16.23 Land North Highland Water Pipe Servitude, No 9 Borgie 0.00 Land Scottish Lowlands East Grange 216.42 Land Scottish Lowlands Tulliallan 81.00 Land Scottish Lowlands Wester Mosshat (Horberry) (Lease) 101.17 Other Scottish Lowlands Cochnohill (1 & 2) 556.31 Other Scottish Lowlands Knockmountain 197.00 Other Tay Land at Blackcraig Farm, Blairgowrie -

Sweetheart Abbey and Precinct Walls Statement of Significance

Property in Care (PIC) ID: PIC216 Designations: Scheduled Monument (SM90293) Taken into State care: 1927 (Guardianship) Last reviewed: 2013 STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE SWEETHEART ABBEY AND PRECINCT WALLS We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH © Historic Environment Scotland 2018 You may re-use this information (excluding logos and images) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/version/3/ or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected] Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Any enquiries regarding this document should be sent to us at: Historic Environment Scotland Longmore House Salisbury Place Edinburgh EH9 1SH +44 (0) 131 668 8600 www.historicenvironment.scot You can download this publication from our website at www.historicenvironment.scot Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH SWEETHEART ABBEY SYNOPSIS Sweetheart Abbey is situated in the village of New Abbey, on the A710 6 miles south of Dumfries. The Cistercian abbey was the last to be set up in Scotland. -

The Norse Influence on Celtic Scotland Published by James Maclehose and Sons, Glasgow

i^ttiin •••7 * tuwn 1 1 ,1 vir tiiTiv^Vv5*^M òlo^l^!^^ '^- - /f^K$ , yt A"-^^^^- /^AO. "-'no.-' iiuUcotettt>tnc -DOcholiiunc THE NORSE INFLUENCE ON CELTIC SCOTLAND PUBLISHED BY JAMES MACLEHOSE AND SONS, GLASGOW, inblishcre to the anibersitg. MACMILLAN AND CO., LTD., LONDON. New York, • • The Macmillan Co. Toronto, • - • The Mactnillan Co. of Canada. London, • . - Simpkin, Hamilton and Co. Cambridse, • Bowes and Bowes. Edinburgh, • • Douglas and Foults. Sydney, • • Angus and Robertson. THE NORSE INFLUENCE ON CELTIC SCOTLAND BY GEORGE HENDERSON M.A. (Edin.), B.Litt. (Jesus Coll., Oxon.), Ph.D. (Vienna) KELLY-MACCALLUM LECTURER IN CELTIC, UNIVERSITY OF GLASGOW EXAMINER IN SCOTTISH GADHELIC, UNIVERSITY OF LONDON GLASGOW JAMES MACLEHOSE AND SONS PUBLISHERS TO THE UNIVERSITY I9IO Is buaine focal no toic an t-saoghail. A word is 7nore lasting than the world's wealth. ' ' Gadhelic Proverb. Lochlannaich is ànnuinn iad. Norsemen and heroes they. ' Book of the Dean of Lismore. Lochlannaich thi'eun Toiseach bhiir sgéil Sliochd solta ofrettmh Mhamiis. Of Norsemen bold Of doughty mould Your line of oldfrom Magnus. '' AIairi inghean Alasdair Ruaidh. PREFACE Since ever dwellers on the Continent were first able to navigate the ocean, the isles of Great Britain and Ireland must have been objects which excited their supreme interest. To this we owe in part the com- ing of our own early ancestors to these isles. But while we have histories which inform us of the several historic invasions, they all seem to me to belittle far too much the influence of the Norse Invasions in particular. This error I would fain correct, so far as regards Celtic Scotland. -

History of the Lands and Their Owners in Galloway

H.E NTIL , 4 Pfiffifinfi:-fit,mnuuugm‘é’r§ms, ».IVI\ ‘!{5_&mM;PAmnsox, _ V‘ V itbmnvncn. if,‘4ff V, f fixmmum ‘xnmonasfimwini cAa'1'm-no17t§1[.As'. xmgompnxenm. ,7’°':",*"-‘V"'{";‘.' ‘9“"3iLfA31Dan1r,_§v , qyuwgm." “,‘,« . ERRATA. Page 1, seventeenth line. For “jzim—g1'é.r,”read "j2'1r11—gr:ir." 16. Skaar, “had sasiik of the lands of Barskeoch, Skar,” has been twice erroneously printed. 19. Clouden, etc., page 4. For “ land of,” read “lands of.” 24. ,, For “ Lochenket," read “ Lochenkit.” 29.,9 For “ bo,” read “ b6." 48, seventh line. For “fill gici de gord1‘u1,”read“fill Riei de gordfin.” ,, nineteenth line. For “ Sr,” read “ Sr." 51 I ) 9 5’ For “fosse,” read “ fossé.” 63, sixteenth line. For “ your Lords,” read “ your Lord’s.” 143, first line. For “ godly,” etc., read “ Godly,” etc. 147, third line. For “ George Granville, Leveson Gower," read without the comma.after Granville. 150, ninth line. For “ Manor,” read “ Mona.” 155,fourth line at foot. For “ John Crak,” read “John Crai ." 157, twenty—seventhline. For “Ar-byll,” read “ Ar by1led.” 164, first line. For “ Galloway,” read “ Galtway.” ,, second line. For “ Galtway," read “ Galloway." 165, tenth line. For “ King Alpine," read “ King Alpin." ,, seventeenth line. For “ fosse,” read “ fossé.” 178, eleventh line. For “ Berwick,” read “ Berwickshire.” 200, tenth line. For “ Murmor,” read “ murinor.” 222, fifth line from foot. For “Alfred-Peter,” etc., read “Alfred Peter." 223 .Ba.rclosh Tower. The engraver has introduced two figures Of his own imagination, and not in our sketch. 230, fifth line from foot. For “ his douchter, four,” read “ his douchter four.” 248, tenth line. -

1 Executive Note the Justice of the Peace Courts

EXECUTIVE NOTE THE JUSTICE OF THE PEACE COURTS (SHERIFFDOM OF TAYSIDE, CENTRAL AND FIFE) ORDER 2008 SSI/2008/363 1. The above Order was made in exercise of the powers conferred by sections 59(2), 64(1) and (4), 65(1), and 81(2) of the Criminal Proceedings etc. (Reform) (Scotland) Act 2007 (“the 2007 Act”). The instrument is subject to negative resolution procedure. 2. This Order provides for justice of the peace courts (“JP courts”) in the Sheriffdom of Tayside, Central and Fife. Certain transitional provisions in the Order will enter into force on 1 December 2008 while the remainder of the Order comes into force on 23 February 2009. The Order makes provision in relation to: • the establishment of JP courts in Tayside, Central & Fife; • the disestablishment of the district courts in Tayside, Central & Fife; • the transfer of staff of the district courts to the employment of the Scottish Ministers; • certain fixed penalties and conditional offers of penalties that will be dealt with by the clerks to the JP courts; • citation of accused persons and witnesses to the JP courts in Tayside, Central & Fife prior to their establishment; • the fixing of diets in the JP courts prior to their establishment, and applications for the alteration of such diets; and • the repeal of certain sections of the District Courts (Scotland) Act 1975 (“the 1975 Act”), for the purposes of court unification in Tayside, Central & Fife. Policy Objectives 3. The 2007 Act makes provision for the unification of Scotland’s courts to allow for the more efficient, effective and consistent handling of criminal cases through the summary courts. -

SCS1H 1 Justice Committee Scottish Court Service Recommendations for a Future Court Structure in Scotland Written Submission

SCS1H Justice Committee Scottish Court Service recommendations for a future court structure in Scotland Written submission from Andrew G Ferguson Haddington Sheriff Court I have read the Scottish Court Service document on “ Shaping Scotland’s Court Services; a dialogue on Court Structure for the Future”, listened to the presentation from Eric McQueen and the arguments against put forward by the Legal fraternity in East Lothian. I have attempted to refrain from making comment and hoping that “common sense” would prevail but alas I sense that it is not as common as I envisaged since the Justice Secretary, Mr Kenneth MacAskill has approved the recommendations and it was subsequently approved by the Scottish Parliament. I would therefore make a few points which would I hope be worthy of consideration by the Justice Committee. These are as follows:- 1. In Appendix 1 of the above document, in part D it is desirable that criminal justice be delivered locally as this engages the local community in the administration of Justice. How can this be perceived by the population of East Lothian, which extends well beyond East of Haddington as to be fair, if the justice is administered from Edinburgh? How would the citizens of Edinburgh view justice being administered from Haddington ? I would suspect that it would not be acceptable and not credible. 2. The use of Video conferencing ( part F of Appendix 1)would seem to be a way dealing with justice in East Lothian by remote administration in Edinburgh. I would suggest that this could be appropriate in some instances but if earnestly developed to cover the majority of cases there are hidden costs which have not been considered and would ultimately be more expensive.