LH Bulletin 3 English

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Secondary School Geography Teaching Resource for Years 7 to 10 1 ISBN: 978-0-9872763-2-2

A secondary school geography teaching resource for Years 7 to 10 1 ISBN: 978-0-9872763-2-2 Published by: One World Centre (Global Education Project) © Commonwealth of Australia, 2014 Creative Commons-Non-Com-Share Alike Australia license, as specified in the Australian Government Open Acess and licensing framework 2011. Some rights reserved. This project was funded by the Australian Government’s Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. (DFAT) Written by: Nuella Flynn Graphic Design by: www.eddshepherd.com Thanks also to: Kylie Hosking, Cameron Tero, Orla Hassett, Alison Bullock, Jenni Morellini and Genevieve Hawks. Cover photo: Chowpatty Inequality Image by Shreyans Bhansali (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0) About the photo: A child looks across the bay at Nariman Point, Mumbai, some of the most expensive land in the world. The views expressed in this publication are not necessarily those of the Global Education Project, or the Australian Government. 2 Contents Introduction ............................................................................................. 2 Year 7 Community ................................................................................... 4 Curriculum Links .................................................................................. 5 Rumour Clinic ...................................................................................... 6 What makes a community liveable? ..................................................... 8 Examining liveability in communities experiencing poverty .................. 11 Views of the local -

Environmental Health in East Timor

WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION SEA-EH-536 Regional Office for South-East Asia 27 May 2002 Distribution: Restricted New Delhi ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH IN EAST TIMOR Assignment Report: 23 November 2000 – 2 March 2001 Mr Sharad Adhikary WHO Short-term Consultant WHO Project: TMP EHA 020 The contents of this restricted document may not be divulged to persons other than those to whom it has been originally addressed. It may not be further distributed nor reproduced in any manner and should not be referenced in bibliographical matter or cited CONTENTS Page 1. PURPOSE OF ASSIGNMENT 1 2. INTRODUCTION 1 3. SITUATION ANALYSIS 1 4. ACTIVITIES UNDERTAKEN 3 5. CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS 4 6. ACKNOWLEDGEMENT 7 SEA -EH-536 1. PURPOSE OF ASSIGNMENT (1) To assist in the development and implementation of environmental health programmes including solid waste management, and community water supply and sanitation; (2) To establish plans for maximizing the benefits of water supply and sanitation to health, assisting in water resources development and preparing proposals for interagency cooperation; (3) To advise and assist in the assessment, preparation, and development of plans for control of major environmental health hazard; (4) To prepare technical reports giving critical analysis of programme impacts, and (5) To advise the WHO Head of Office on all matters pertaining to environmental health activities as required. 2. INTRODUCTION Immediately after the referendum in September 1999, East Timor experienced extensive destruction of most of the infrastructure facilities, public buildings, thousands of private homes and business. With the re-establishment of the government institutions under UNTAET (United Nations Transitional Administration in East Timor) at present, the general administration and rebuilding of the ruined infrastructures are being streamlined. -

Report (1997), Only Five African Countries Have a Lower GDP Per Capita Than East Timor’S Post- Crisis $US168 Per Capita

CHAPTER 2 ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT The East Timor economy1 2.1 The Indonesian withdrawal from East Timor in September 1999, accompanied by a campaign of violence, killings, massive looting and destruction of property and infrastructure, forced transportation of large numbers of people to West Timor and the flight of most of the rest of the population from their homes, left the East Timor economy in ruin. This section, therefore, largely describes the economy as it was prior to the Indonesian withdrawal, the remains of which must serve as the foundations for the economy of an independent East Timor. 2.2 DFAT submitted that East Timor has always been principally a subsistence economy. Much economic activity occurred through barter, which was not captured in GDP figures. Economic statistics for East Timor were scarce and unreliable, as was detailed information about economic activity. DFAT stated that: Preliminary figures from the Indonesian Government Bureau of Statistics (BPS) indicate that East Timor’s 1998 GDP was Rp1405 billion ($US148 million) using an average annual exchange rate of for 1998 of Rp9514/$US. GDP per capita was approximately $US168 in 1998. Largely reflecting conditions before the Indonesian economic crisis, East Timor’s GDP (at current market prices) in 1997 was Rp996 billion ($US343 million). East Timor’s GDP accounts for a tiny 0.15% of Indonesia’s national GDP. According to the BPS, per capita GDP was Rp1.1 million ($US379) compared with a national GDP per capita of Rp3.1 million ($US1,068). According to the World Bank’s World Development Report (1997), only five African countries have a lower GDP per capita than East Timor’s post- crisis $US168 per capita. -

Portugal:T Imor

INDICATIVE COOPERATION PROGRAMME [2004-2006] INSTITUTO PORTUGUÊS DE APOIO AO DESENVOLVIMENTO Portugal COOPERAÇÃO DEVELOPMENT Portugal:Timor INDICATIVE COOPERATIONPROGRAMME Portugal:Timor [2004-2006] Published by Instituto Português de Apoio ao Desenvolvimento Design ATELIER B2: José Brandão Teresa Olazabal Cabral Print Textype ISBN: 972-99008-6-8 Legal Deposit: 210 992/04 MAY 2004 Contents 1. Framework [5] 1.1. Background [6] 1.2. National Development Plan for East Timor [7] 2. ICP General and Specific Principles [10] 2.1. Priority Sectors [10] 2.1.1. Education and support to the reintroduction of the Portuguese Language [10] 2.1.2. Institutional Capacitation [12] 2.1.3. Support to Economic and Social Development [15] 2.1.4. Other Interventions [18] 3. Financial Framework [19] 4. Monitoring and Assessment [19] Appendix [21] MEMORANDUM OF UNDERSTANDING BETWEEN THE GOVERNMENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF PORTUGAL AND THE GOVERNMENT OF THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF EAST TIMOR 1. Framework 1.1 Background Since August 1999, when following a popular consultation the Timorese freely decided on their future, Portugal has been dedicated to the process for the rebuilding and development of East Timor. This dedication, which is reflected in the different Portuguese cooperation bilateral and multilateral projects, has gone through three different stages – humanitarian emergency aid, rebuilding and development support – and has always focused on the direct requests made by the legitimate representatives of the Timorese people. The first Indicative Cooperation Programme appear in the year 2000, its purpose being to transform emergency aid objectives into development aid objectives. It was thus that the attempt to support the creation and subse- quent consolidation of the Timorese State was made, based on universal principles. -

![Development and Disadvantage in Eastern Indonesia [PDF,7.39MB]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0843/development-and-disadvantage-in-eastern-indonesia-pdf-7-39mb-2550843.webp)

Development and Disadvantage in Eastern Indonesia [PDF,7.39MB]

ll1 The Network ttt! The Development Studies Network Ltd is a registered, not for profit, organisation that provides information and discussion on social and economic development issues. It publishes a quarterly journal, Development Bulletin, runs regular seminars on developing policy and annual conferences on international development. Members of the Network are encouraged to contribute information and papers to the Development Bulletin. Subscription to the Development Bulletin includes membership of the Network. This allows you to publicise in the Development Bulletin information about new development-related books, papers, journals, courses or conferences. Being a member of the Network allows you special discounts to Network seminars and conferences. ll1 Network Office Bearers ttt! National Patron Advisory Board The Right Honourable Mr Ian Sinclair Janet Hunt, Executive Director, ACFOA Dr John Browett, Dean, School of Social Sciences and Board of Directors Director Development Studies Centre, Flinders University Dr Pamela Thomas Professor Fred Deyo, Director, Institute for Development Associate Professor Joe Remenyi, Deakin University Studies, University of Auckland Dr Robert Crittenden, ANUTECH Pty Ltd Professor John Overton, Director, Development Studies Dr Elspeth Young, Australian National University Centre, Massey University Dr Gary Simpson, Project Management and Design Pty Ltd Dr Eci Nabalarua, University of South Pacific, Suva Professor Gavin Jones, Australian National University Dr Terry Hull, Director, Demography Program, Australian Dr Sharon Bessell, Australian National University National University Dr Malama Meleisea, UNESCO, Bangkok Editorial Board Mr Bob McMullan, MP, Canberra Dr Pamela Thomas, Managing Editor Associate Professor Mark McGillivray, International Dr Penelope Schoeffel, University of Auckland Development Programme, RMIT University Dr Elspeth Young, Australian National University Professor Dick Bedford, University of Waikato Editor Professor Dean Forbes, Flinders University Pamela Thomas Professor R. -

East Timor Medical Elective, Bairo Pite Clinic; April – May 2011

Maternal health in East Timor Medical Elective, Bairo Pite Clinic; April – May 2011 Introduction The democratic republic of Timor-Leste (East Timor) resides on the south eastern extremity of the Indonesian archipelago, it has been independent since 1999, when the Indonesian occupation ended. The violent and bloody nature of the Indonesian withdrawal meant few escaped persecution and a large proportion of the nation’s infrastructure was destroyed. Currently East Timor is considered to be one of the ten poorest countries in the world with more than 40% of civilians living below the poverty line and the health care expenditure per capita An outreach clinic in Kasnafa, a rural district around being a mere US$58 in 20071. The Ministry 50 miles from the capital city, Dili of Health (MoH) was established in 2002 to In light of this I decided that maternal health in address the gap in medical provision in East East Timor was a fitting and worthwhile focus Timor, but despite this many of the nation’s for my medical elective. I carried out my health care needs remain largely unmet. placement at the Bairo Pite clinic (BPC) in the heart of the nation’s capital, Dili. BPC has Maternal health is a particular neglected been directed by Dr Dan Murphy since the aspect of the health care system with an occupation ended, re-utilising an old military estimated maternal mortality rate (MMR) of clinic as a public health outlet. It is funded 830 per 100,000 live births and an infant primarily by non-governmental organizations mortality rate (IMR) of 80-90 per 1,000 live (NGOs) and charity, and has evolved from a births2,3. -

National Development Plan

NATIONAL DEVELOPMENT PLAN After independence on 20 May 2002, the draft Plan will be presented to the Parliament for consideration and adoption. Planning Commission Dili May 2002 Table of Contents LIST OF ACRONYMS AND GLOSSARY...........................................................................................III Foreword.......................................................................................................................................VI Foreword......................................................................................................................................VII VISION......................................................................................................................................... VIII EXECUTIVE SUMMARY INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 1 DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY......................................................................................................... 1 POVERTY REDUCTION STRATEGY .............................................................................................. 2 CAPACITY BUILDING FOR PLAN IMPLEMENTATION ................................................................... 3 MONITORING,EVALUATION, AND PLANNING REVIEW .............................................................. 5 MACROECONOMICS AND PUBLIC FINANCE POLICY FRAMEWORK.............................................. 5 MEDIUM TERM ECONOMIC AND FINANCING OUTLOOK ............................................................ -

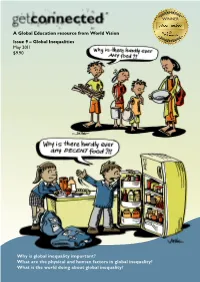

Global Inequality

WINNER A Global Education resource from World Vision Issue 9 – Global Inequalities May 2011 $9.90 Why is global inequality important? What are the physical and human factors in global inequality? What is the world doing about global inequality? Contents Issue 9 – Global Inequalities Contents Poverty on our doorstep 3 Poverty on our doorstep Global inequality 4-5 Human Development Index 6-7 World Vision, a non-government organisation (NGO) is My name is Aaron. I’m just an ordinary 18 year old, working with these families and their communities. What is poverty? 8-9 but three months out of school I was boarding a plane to East Timor as a World Vision Youth Ambassador. I met farmers who had been given training and were Poverty and hunger 10-11 Just an hour flight from Darwin and I found myself in a now reaping crops four times bigger than ever before. whole other world – a world of injustice and poverty, a I met other families who now not only had enough Give a man a fish ... some poems 12-13 world that together we must change. I had heard about food for themselves but were selling produce to Physical and human factors 14-15 poverty, seen pictures of poverty, even talked about supermarkets. World Vision works in partnership with poverty, but never before have I been exposed to such communities so the people believe in themselves again East Timor – an information report 16-17 raw and uncensored poverty. and see a way out of their situation.They give training and hope. -

Economic and Social Rights

Chapter 7.9: Economic and Social Rights Chapter 7.9: Economic and Social Rights.............................................................................................1 Chapter 7.9: Economic and Social Rights.............................................................................................2 7.9.1 Introduction ...............................................................................................................................2 The Commission’s work on economic and social rights..............................................................5 Social and economic rights and other rights ................................................................................6 7.9.2 The right to an adequate standard of living.............................................................................7 Development and government spending......................................................................................8 The coffee sector.........................................................................................................................11 Right of a people to dispose of natural resources......................................................................16 The right to food...........................................................................................................................18 Housing and land.........................................................................................................................23 7.9.3 Right to Health ........................................................................................................................28 -

Development of Tourism Policy and Strategic Planning in East Timor

Volume 8 Number 1 2001 ISSN 1 440-947X ISBN 186 499 506 8 DEVELOPMENT OF TOURISM POLICY AND STRATEGIC PLANNING IN EAST TIMOR Prepared by R. W. (Bill) Carter School of Natural and Rural Systems Management The University of Queensland Bruce Prideaux Department of Tourism and Leisure Management The University of Queensland with Vicente Ximenes School of Natural and Rural Systems Management The University of Queensland FRETILIN Member and Adrien V. P. Chatenay Griffith University Occasional Paper 2001 8(1):1-101 Carter, R. W., Prideaux, B., Ximenes, V. and Chatenay, A. V. P. Occasional Paper 2001 8(1) Authors’ note On 5 May 1999, it was announced from New York by the United Nations that ‘popular consultation’ would be held in East Timor to determine its political future as an independent nation or an autonomous state within Indonesia. After a number of delays, the newly elected Indonesian President, B. J. Habibie, announced that the referendum would occur on 30 August 1999, overseen by the United Nations. On 10 May 1999, Mr Vicente Ximenes, an expatriate East Timorese, FRETILIN leader and recent graduate from the University of Queensland approached Dr Bill Carter of the University for assistance in planning for tourism development in East Timor. Together, they prepared initial tourism input to the Strategic Development Planning for East Timor Conference, Melbourne Australia, 5-9 April 1999. Subsequent advice on tourism matters was sought, through Mr Ximenes, by the CNRT (National Council for the Timorese Resistance). Dr Bruce Prideaux of the University joined the small team to expand on the advice. -

Internal Migration and Development in East Timor in the School of People

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. INTERNAL MIGRATION AND DEVELOPMENT IN EAST TIMOR AureIio Sergio Cristovao Guterres 2003 " Massey University School of People COLLEGE OF HUMANITIES & SOCIALSCIENCES Environment' and Planning Private Bag 11 222. Palmerston North. New Zealand Telephone: 64 6 350 5799 Facsimile: 64 6 350 5737 TO WHOM IT MAYCONCERN This is to state that the research carried out for my Doctoral thesis entitled "Internal Migration and Development in East Timor" in the School of People, Environment and Planning, Massey University, Turitea, New Zealand is all my own work. This is also to certify that the thesis material has not been used for any other degree. Te Kunenga ki Purehuroa Inception to Infinity: Massey University's commiunent to learning as a life-long journey o MasseyUniversity School of People COLLEGE OF HUMANITIES & SOCIAL SCIENCES Environment and Planning Private Bag 11 222. - �- Palmerston North. -� New Zealand Telephone: 64 6 350 5799 Facsimile: 64 6 350 5737 TOWHOM IT MAY CONCERN This is to st at e the research carried out for the Doctoral thesis entitled"Internal Migration and Development in East Timor" was done by Aurelio Sergio Cristovao Guterres in the School of People, Environment and Planning, Massey University, Tu ritea , New Zealand. The thesis material has not been used for any other degree, and the candidate has pursued the course of study in accordance with the requirements of the Massey University regulations. -

General Assembly Official Records

United Nations A/AC.109/PV.1444 General Assembly Official Records Special Committee on the Situation with Regard to the Implementation of the Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples 1444th Meeting Tuesday, 11 July 1995, 3 p.m. New York Acting Chairman: Mr. Bangura .................................. (Sierra Leone) The meeting was called to order at 3.40 p.m. Question of East Timor (A/AC.109/2026) (continued) The Chairman: Let me first express my regret that The Chairman: We shall now continue the hearings there has not been a positive response to the appeal that I on the question of East Timor. made at the end of the last meeting. Instead of beginning at three o’clock, as I hoped, we are starting almost 45 minutes At the invitation of the Chairman, Mr. Max B. late. This delay will have an adverse impact on our Surjadinata (East Timor Religious Outreach) took a deliberations, and I can only hope that it will not be place at the Committee table. repeated. The Chairman: I call on Mr. Surjadinata. I should like in particular to repeat my appeal to the petitioners that they adhere to the limit of 15 minutes. Mr. Surjadinata (East Timor Religious Outreach): I am Rev. Max Surjadinata, pastor of Mount Vernon Requests for hearing Heights Congregational Church in Mount Vernon, New York, a social worker and north-eastern Coordinator of The Chairman: I wish to draw members’ attention to East Timor Religious Outreach in the United States. the additional requests for hearing, which have been circulated in aides-mémoire 5/95/Add.3 and 14/95, relating The testimony I am presenting was prepared by the respectively to East Timor and the United States Virgin National Coordinator of East Timor Religious Outreach, Islands.