Read These Fragments of an Autobiography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Archaeological Papers Published

INDEX OF ARCHAEOLOGICAL PAPERS PUBLISHED IN 1907 [BEING THE SEVENTEENTH ISSUE OF THE SERIES AND COMPLETING THE INDEX FOR THE PERIOD 1891-1907] COMPILED BY BERNARD GOMME PUBLISHED BY ARCHIBALD CONSTABLE & COMPANY LTD 10, ORANGE STREET, LEICESTER SQUARE, W.C. UNDER THE DIRECTION OF THE CONGRESS OF ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETIES IN UNION WITH THE SOCIETY OF ANTIQUARIES 1908 CONTENTS [Those Transactions for the first time included in the index are marked with an asterisk,* the others are continuations from the indexes of 1891-190G. Transactions included for the first time are indexed from 1891 onwards.} Anthropological Institute, Journal, vol. xxxvii. Antiquaries, Ireland, Proceedings of Royal Society, vol. xxxvii. Antiquaries, London, Proceedings of Royal Society, 2nd S. vol. xxi. pt. 2. Antiquaries, Newcastle, Procceedings of Society, vol. x., 3rd S. vol. ii. Antiquaries, Scotland, Proceedings of Society, vol. xli. Archaoologia ^Eliana, 3rd S. vol. iii. Archssologia Cambrensis, 6th S. vol. vii. Archaeological Institute, Journal, vol. Ixiv. Berks, Bucks and Oxfordshire Archaeological Journal, vols. xii. (p. 97 to end), xiii. Biblical Archsoology, Society of, Proceedings, vol. xxix. Birmingham and Midland Institute, Transactions, vol. xxxii. Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society, Transactions, vols. xxix. pt. 2, xxx. pt. 1 (to p. 179). British Academy, Proceedings, 1905 and 1900. British Archieological Association, Journal, N.S. vol. xiii. British Architects, Royal Institute of, Journal, 3rd S. vol. xiv. British Numismatic Journal, 1st S. vol. iii. British School at Athens, Annual, vol. xii. British School at Rome, Papers, vol. iv. Buckinghamshire Architectural and Archaeological Society, Records, vol. ix. pt. 4 (to p. 324). Cambridge Antiquarian Society, Transactions, vol. -

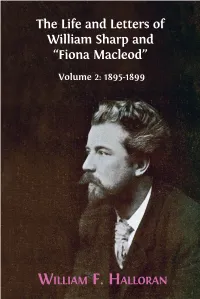

The Life and Letters of William Sharp and “Fiona Macleod”

The Life and Letters of William Sharp and “Fiona Macleod” Volume 2: 1895-1899 W The Life and Letters of ILLIAM WILLIAM F. HALLORAN William Sharp and What an achievement! It is a major work. The lett ers taken together with the excellent H F. introductory secti ons - so balanced and judicious and informati ve - what emerges is an amazing picture of William Sharp the man and the writer which explores just how “Fiona Macleod” fascinati ng a fi gure he is. Clearly a major reassessment is due and this book could make it ALLORAN happen. Volume 2: 1895-1899 —Andrew Hook, Emeritus Bradley Professor of English and American Literature, Glasgow University William Sharp (1855-1905) conducted one of the most audacious literary decep� ons of his or any � me. Sharp was a Sco� sh poet, novelist, biographer and editor who in 1893 began The Life and Letters of William Sharp to write cri� cally and commercially successful books under the name Fiona Macleod. This was far more than just a pseudonym: he corresponded as Macleod, enlis� ng his sister to provide the handwri� ng and address, and for more than a decade “Fiona Macleod” duped not only the general public but such literary luminaries as William Butler Yeats and, in America, E. C. Stedman. and “Fiona Macleod” Sharp wrote “I feel another self within me now more than ever; it is as if I were possessed by a spirit who must speak out”. This three-volume collec� on brings together Sharp’s own correspondence – a fascina� ng trove in its own right, by a Victorian man of le� ers who was on in� mate terms with writers including Dante Gabriel Rosse� , Walter Pater, and George Meredith – and the Fiona Macleod le� ers, which bring to life Sharp’s intriguing “second self”. -

The Blackmore Country (1906)

I II i II I THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES IN THE SAME SERIES PRICE 6/- EACH THE SCOTT COUNTRY THE BURNS COUNTRY BY W. S. CROCKETT BY C. S. DOOGALL Minister of Twccdsmuir THE THE THACKERAY COUNTRY CANTERBURY PILGRIMAGES BY LEWIS MELVILLE BY II. SNOWDEN WARD THE INQOLDSBY COUNTRY THE HARDY COUNTRY BY CHAS. G. HAKI'ER BY CHAS. G. HARPER PUBLISHED BY ADAM AND CHARLES BLACK, SOHO SQUARE, LONDON Zbc pWQVimnQC Series CO THE BLACKMORE COUNTRY s^- Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2007 with funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation http://www.archive.org/details/blackmorecountryOOsneliala ON THE LYN, BELOW BRENDON. THE BLACKMORE COUNTRY BY F. J. SNELL AUTHOR OF 'A BOOK OF exmoob"; " kably associations of archbishop temple," etc. EDITOR of " UEMORIALS OF OLD DEVONSHIRE " WITH FIFTY FULL -PAGE ILLUSTRATIONS FROM PHOTOGRAPHS BY C. W. BARNES WARD LONDON ADAM AND CHARLES BLACK 1906 " So holy and so perfect is my love, That I shall think it a most plenteous crop To glean the broken ears after the man That the main harvest reaps." —Sir Phiup SroNEY. CORRIGENDA Page 22, line 20, for " immorality " read " morality." „ 128, „ 2 1, /or "John" r^a^/" Jan." „ 131, „ 21, /<7r "check" r?a^ "cheque." ; PROLOGUE The " Blackmore Country " is an expression requiring some amount of definition, as it clearly will not do to make it embrace the whole of the territory which he annexed, from time to time, in his various works of fiction, nor even every part of Devon in which he has laid the scenes of a romance. -

The Delius Society Journal Spring 2000, Number 127

Delius Journal 127.qxd 10-04-2000 09:18 Page 1 The Delius Society Journal Spring 2000, Number 127 The Delius Society (Registered Charity No. 298662) Full Membership and Institutions £20 per year UK students: £10 per year USA and Canada US$38 per year Africa, Australasia and Far East £23 per year President Felix Aprahamian Vice Presidents Roland Gibson MSc, PhD (Founder Member) Lionel Carley BA, PhD Meredith Davies CBE Sir Andrew Davis CBE Vernon Handley MA, FRCM, D Univ (Surrey) Richard Hickox FRCO (CHM) Rodney Meadows Robert Threlfall Chairman Lyndon Jenkins Treasurer and Membership Secretary Derek Cox Mercers, 6 Mount Pleasant, Blockley, Glos GL56 9BU Tel: (01386) 700175 Secretary Anthony Lindsey 1 The Pound, Aldwick Village, West Sussex PO21 3SR Tel: (01243) 824964 Delius Journal 127.qxd 10-04-2000 09:18 Page 2 Editor Roger Buckley 57A Wimpole Street, London W1M 7DF (Mail should be marked ‘The Delius Society’) Tel: 020 7935 4241 Fax: 020 7935 5429 email: [email protected] Assistant Editor Jane Armour-Chélu 17 Forest Close, Shawbirch, Telford, Shropshire TF5 0LA Tel: (01952) 408726 email: [email protected] Website: http://www.delius.org.uk email: [email protected] ISSN-0306-0373 Delius Journal 127.qxd 10-04-2000 09:18 Page 3 CONTENTS Chairman’s Message........................................................................................... 5 Editorial................................................................................................................ 6 ORIGINAL ARTICLES Delius and Verlaine, by Robert Threlfall............................................................ 7 Vilhelmine, the Muse of Sakuntala, by Hattie Andersen................................ 11 Delius’s Five Songs from Tennyson’s Maud, by Christopher Redwood.......... 16 The ‘Old Cheshire Cheese’Connection, by Jane Armour-Chélu.................... 22 Delius and the American Connections, by George Little.............................. -

Somerset. Kl~Gsbury

DIRECTORY.] SOMERSET. KL~GSBURY. 301 West Somerset branch of the Great Western railway and left; this, which is now used as a mortuary chapel, con. 12 north-west from Bridgwlllter. The church of St. tains a fine Norman font. The register dates from the Andrew was pulled down when the parish was ecclesiasti- year 1654. The area and population is included with cally annexed to Kilton in 1881, the chancel only being I Kilton. KILTO~. COMMERCIAL. LILSTOCK. J.oseph Mrs. Woodlands house, near Holford. Bridgwater Clark Christopher & WaIter, farmers Evered Reginald, farmer Shedden Rev. Samuel Hunter M.A. Creech Barnet, farmer, Moorhouse fm Morris Edwin, bailiff to Capt. Sir A. Vicarage lEvered George, farmer, Plud farm Fuller-Acland-Hood bart. M.P KILVE is a pleasant village and parish, bounded on the 150 volumes. KiLve Court is the residence of Daniel Bad north by the Bristol Channel and by the road from Bridg- cock esg. J.P. George Fownes Luttrell esg. of Dunster water to Minehead, 5 miles east-north-east from Williton Castle, who is lord of the manor, Mrs. Pritchard, Daniel station on the West Somerset branch of tlte Great Western Badcock esg. J.P. and Capt. Sir A. Fuller-Acland-Hood Tailway and 12 north-west-by-west from Bridgwater, in bart. M.P. are the principal landowners. The soil is the Western division of the county, hundred of Williton stony rush, with some clay; subsoil, marl and gravel, and Freemanors, Williton petty sessional division, union and produces good crops of wheat, oats, barley, mangolds, and county court district, rural deanery of Quantoxhead, potatoes and turnips. -

Ankenym Powysjournal 1996

Powys Journal, 1996, vol. 6, pp. 7-61. ISSN: 0962-7057 http://www.powys-society.org/ http://www.powys-society.org/The%20Powys%20Society%20-%20Journal.htm © 1996 Powys Society. All rights reserved. Drawing of John Cowper Powys by Ivan Opffer, 1920 MELVON L. ANKENY Lloyd Emerson Siberell, Powys 'Bibliomaniac' and 'Extravagantic' John Cowper Powys referred to him as 'a "character", if you catch my meaning, this good Emerson Lloyd S. — a very resolute chap (with a grand job in a big office) & a swarthy black- haired black-coated Connoisseur air, as a Missioner of a guileless culture, but I fancy no fool in his office or in the bosom of his family!'1 and would later describe him as 'a grand stand-by & yet what an Extravagantic on his own our great Siberell is for now and for always!'2 Lloyd Emerson Siberell, the 'Extravagantic' from the midwestern United States, had a lifelong fascination and enthusiasm for the Powys family and in pursuit of his avocations as magazine editor, publisher, writer, critic, literary agent, collector, and corresponding friend was a constant voice championing the Powys cause for over thirty years. Sometimes over-zealous, always persistent, unfailingly solicitous, both utilized and ignored, he served the family faithfully as an American champion of their art. He was born on 18 September 1905 and spent his early years in the small town of Kingston, Ohio; 'a wide place in the road, on the fringe of the beautiful Pickaway plains the heart of Ohio's farming region, at the back door of the country, so to speak.' In his high school days he 'was always too busy reading the books [he] liked and playing truant to ever study seriously...' He 'enjoyed life' and was 'a voracious reader but conversely not the bookworm type of man.'3 At seventeen he left school and worked a year at the Mead Corporation paper mill in Chillicothe, Ohio and from this experience he dated his interest in the art and craft of paper and paper making. -

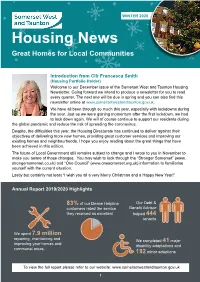

SWT Housing Newsletter 2020

WINTER 2020 Housing News Great Homes for Local Communities Introduction from Cllr Francesca Smith (Housing Portfolio Holder) Welcome to our December issue of the Somerset West and Taunton Housing Newsletter. Going forward we intend to produce a newsletter for you to read every quarter. The next one will be due in spring and you can also find this newsletter online at www.somersetwestandtaunton.gov.uk. We have all been through so much this year, especially with lockdowns during the year. Just as we were gaining momentum after the first lockdown, we had to lock down again. We will of course continue to support our residents during the global pandemic and reduce the risk of spreading the coronavirus. Despite, the difficulties this year, the Housing Directorate has continued to deliver against their objectives of delivering more new homes, providing great customer services and improving our existing homes and neighbourhoods. I hope you enjoy reading about the great things that have been achieved in this edition. The future of Local Government still remains subject to change and I wrote to you in November to make you aware of those changes. You may wish to look through the “Stronger Somerset” (www. strongersomerset.co.uk) and “One Council” (www.onesomerset.org.uk) information to familiarise yourself with the current situation. Lastly but certainly not least “I wish you all a very Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year!” Annual Report 2019/2020 Highlights 83% of our Deane Helpline Our Debt & customers rated the service Benefit Advisor they received as excellent helped 444 tenants We spent 7.9 million repairing, maintaining and We completed 41 major improving your homes and disability adaptations and communal areas. -

Congress of Archaeological Societies, 1916

CONGRESS OF ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETIES, 1916. REPORT OF THE COMMITTEE ON ANCIENT EARTHWORKS and FORTIFIED ENCLOSURES. Chairman : The Rt. Hon. the EARL OF CRAWFORD AND BALCARRES, LL.D., F.S.A. Committee : A. HADRIAN ALLCROFT, M.A. W. M. I'ANSON, F.S.A. Col. F. W. T. ATTREE, F.S.A. H. LAYER, F.S.A. G. A. AUDEN, M.A., M.D., F.S.A. C. LYNAM, F.S.A. C. H. BOTHAMLEY, M.Sc., F.I.C. D. H. MONTGOMERIE, F.S.A. Lieut. A. G. CHATER, R.N.R. Col. W. LL. MORGAN. J. G. N. CLIFT. T. DAVIES PRYCE. W. G. COLLINGWOOD, M.A., F.S.A. Sir HERCULES READ, LL.D., WlLLOUGHBY GARDNER, F.S.A. F.B.A., V.P.S.A. H. ST. GEORGE GRAY. Col. O. E. RUCK, F.S.A. (Scot.) Professor F. HAVERFIELD, LL.D., W. M. TAPP, LL.D.,' F.S.A. D.Litt., F.B.A., F.S.A. J. P. WILLIAMS-FREEMAN, M.D. Sir W. ST. JOHN HOPE, M.A., Litt.D., D.C.L. Hon. Secretary : ALBANY F. MAJOR, 30, The Waldrons, Croydon. REPORT OF THE EARTHWORKS COMMITTEE. HE Earthworks Committee again ask indulgence for any shortcomings in their Report. All the T difficulties referred to in last year's Report still attend the work of the Committee, while Mr. A. G. Chater, who gave invaluable help in the compilation of the last Report, is now a Royal Naval Reserve officer. With regard to the remarks in the last Report about damage to the great dykes in Cambridgeshire, the Committee is informed that no new damage has been done in recent years. -

Megalithic Routes E.V. Brochure 2017

A Culture Route of the Council of Europe Megalithic Routes Karlssteine, Osnabrück (D) Karlssteine, Osnabrück (D) Passage grave Ekornavallen (SE) 4 5 Megalithic culture: A reminder of our common European cultural heritage Ladies and Gentlemen, The phenomenon of megalithic cultures can be found right across the European This remarkable aim would have been unthinkable without the tireless efforts of continent and in the majority of the 28 member states of the European Union. volunteers and dedicated individuals. I am deeply honoured to be patron of These cultural places, many more than 5.000 years old, reveal a common back - “Megalithic Routes e.V.”, which can help us grow closer together as Europeans. ground and serve as a reminder of our common European cultural heritage. It is I am convinced that only by knowing our common European past, we Europeans our responsibility as Europeans to guard these megalithic monuments and to may know who we are and may decide where we want to go in the future. teach the characteristics and purposes of these megalith-building cultures in order to frame this part of our history for future generations. With my best wishes, In order to raise awareness of megalithic cultures, the project “Megalithic Routes e.V.” was brought into being. The intention behind the initiative is to not only ex - plore and protect the monuments, but also to rediscover the touristic value of the findings. This idea to develop a cultural path that runs through megalithic sites in several European countries is the only one of its kind, and is of immeasurable Dr. -

Uncovering Exmoor's Prehistoric Past

PANEL Uncovering Exmoor’s Prehistoric Past Figure A Withypool stone circle (right of centre) in an island of survival amongst areas of medieval ridge and furrow cultivation on Withypool Hill. The circle was discovered in 1898 and is approximately 118 feet in diameter. Originally consisting of around 100 stones, the 37 that survive are most clearly visible against the blackened earth following ‘swaling’ or burning of the moorland heather. The landscape of southern Exmoor contains a wealth of prehistoric remains, surviving best within the former Royal Forest and around its margins. Here, the land has hardly been cultivated since the Bronze Age – except where 9th-century reclamation and improvement have taken place – and we are able to discern the complex remains of early prehistoric communities. South of the Royal Forest, the commons were ploughed in the medieval period and still contain vast tracts of ridge and furrow, which has obliterated all but the most enduring prehistoric features or chance survivals between these later areas of cultivation. Further away still the network of farms and fields, which has its origins in the early medieval period, has almost entirely effaced the prehistoric pattern. Only the most obdurate burial mounds have not been levelled. However, traces of the earlier landscapes from time to time do emerge, and will continue to do so as archaeological techniques improve. Taken together the landscape of southern Figure B Collecting peat cores from a valley mire system Exmoor conveys a story of continual settlement on Molland Common. expansion and contraction around the moors as Halscombe Allotment the remains of an ancient oak climatic, economic and social circumstances permitted. -

Francis Thompson and His Relationship to the 1890'S

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Master's Theses Theses and Dissertations 1947 Francis Thompson and His Relationship to the 1890's Mary J. Kearney Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Kearney, Mary J., "Francis Thompson and His Relationship to the 1890's" (1947). Master's Theses. 637. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses/637 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1947 Mary J. Kearney ii'RJu\fCIS THOi.IPSOH A1fD HIS HELATI01,JSIUP TO Tim 1890'S By Mary J. Kearney A THESIS SUB::iiTTED IN P AHTI.AL FULFILLEENT OF 'riiE HEQUITKii~NTS FOB THE DEGREE OF liil.STEH 01!" ARTS AT LOYOLA UUIV:CflSITY CHICAGO, ILLINOIS June 1947 ------ TABLE OF CO:!TEdT8 CHAPTER PAGE I. Introduction. 1 The heritage of the 1890's--Victorian Liberalis~ Scientific ~laturalism--Intellectual Homanticism Spiritual Inertia--Contrast of the precedi~g to the influence of The Oxford :iJioveo.ent II. Francis Thompson's Iielationsh.in to the "; d <::: • ' 1 ... t ~ _.l:nF ___g_ uleC e \'!rl ers. • •• • • ••••••••• • 17 Characteristics of the period--The decadence of the times--Its perversity, artificiality, egoism and curiosity--Ernest Dawson, the mor bid spirit--Oscar Wilde, the individualist- the Beardsley vision of evil--Thompson's negative revolt--His convictions--The death of the Decadent movement. -

A. Nether Stowey to Alfoxton

A. Nether Stowey to Alfoxton Distance: 4¾ miles the main track, climbing very slightly to the stone Total Ascent: 205 metres cairn marking the highest point of the path. Walk Summary: A steep climb from Nether Ignoring the bridleway to the right, by the marker Stowey, then a steadier ascent to the top of 10 Woodlands Hill. Downhill through heath and cairn, bear left along the main track, heading steeply woodland to Holford and along the level tarmac downhill and into the trees on Woodlands Hill drive to Alfoxton. Much of this section also 11 In the woods the path forks. Bear left to stay on follows a route signed the Quantock Greenway. the main track, still descending steeply through the trees. Carry on past the side path that goes through 1 Coming out of Coleridge Cottage, turn right and a gate on the left a little further on as well. walk down Lime Street, turning right again on Castle Coming out onto a small road just before the Street. At the clock tower bear right to continue 12 ahead along Castle Street and then Castle Hill. A39, turn left to follow it over the crest of a small hill and down into Holford. 2 Carry on down the other side of Castle Hill, past Detour right to visit the church, with its 13th- the site of Nether Stowey Castle, to walk to the T- 13 junction at the bottom of the hill. Turn left here. century churchyard cross, and the site of the Huguenot silk mill (used in a video by singer Bryan 3 About 150 yards ahead, a lane leaves on the right.