SADC Media Law: a Handbook for Media Practioners

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Economic Contribution of Copyright Industries in Botswana

The Economic Contribution of Copyright Industries in Botswana THE ECONOMIC CONTRIBUTION OF COPYRIGHT INDUSTRIES IN BOTSWANA IN INDUSTRIES COPYRIGHT OF CONTRIBUTION ECONOMIC THE The Economic Contribution of Copyright Industries in Botswana GANTCHEV Dimiter 5/6/2019 11:24 THE ECONOMIC CONTRIBUTION OF COPYRIGHT-BASED Style Definition: TOC 2 INDUSTRIES IN BOTSWANA GANTCHEV Dimiter 5/6/2019 11:26 Comment [1]: the table of contents and the study throughout has adopted the term "copyright industries", not copyright- based. Parhaps -based can be deleted. The Economic Contribution of Copyright Industries in Botswana (PHOTOGRAPHS) (Botswana Blue for Cover Page Background) i Prepared by: Botswana Institute for Development Policy Analysis (BIDPA) Lead Consultant: Professor Patrick Malope Ms. Tshepiso Gaetsewe Ms. Masedi K. Tshukudu Ms. Koketso Molefhi Mr. Bathusi Lesolebe Mr. Johnson Maiketso Advisor: International Consultant Professor Dickson Nyariki The Economic Contribution of Copyright Industries in Botswana ISBN: 978-99968-3-063-1 June 2019 Cover images by: Mr. Thalefang Charles (traditional dancers, elephant tusk sculpture, women and stack of books) Kamogelo Ngoma (traditional basket) Cover design by Kamogelo Ngoma Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this survey are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the points of view of the Companies and Intellectual Property Authority. Acknowledgments This report was prepared by the Botswana Institute for Development Policy Analysis (BIDPA) for the Companies and Intellectual Property Authority (CIPA). It was developed using the “Guide on Surveying the Economic Contribution of the Copyright Industries” developed by the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO). Its main aim is to estimate the economic contribution of copyright industries to the national economy of Botswana. -

Southern Africa Media Landscape

SOUTHERN AFRICA MEDIA LANDSCAPE: Malawi, Namibia, Botswana and Zimbabwe Profile compiled by 38 Harvey Brown Road, Milton Park, Harare Zimbabwe Contact: [email protected] Tel: 00263 867 710 8362 1 MALAWI Malawi is a landlocked country and former British colony. Malawi became independent in 1964. Population 16.8 million according to the Government of Malawi https://www.malawi.gov.mw/ Languages English and Chichewa (Chichewa spoken by 75% of the population) are the two officially recognized languages. Other local languages spoken are Lomwe 17%, Yao 20%, Ngoni, 11%, Tumbuka 9%, Nyanja 6%, Sena 4%, Tonga 2% as well as several other languages. Cities and towns Capital City – Lilongwe Commercial capital – Blantyre Government President: Peter Mutharika Currency Kwacha 2 Administrative map of Malawi Source: http://www.nationsonline.org/oneworld/map/malawi-administrative-map.htm 3 Summary of Media ▪ Two (2) State owned radio stations ▪ Twenty-four (24) Community radio stations ▪ Ten (10) Privately owned radio stations with national reach ▪ Ten (10) Television stations ▪ One (1) Government news agency ▪ Thirteen (13) Privately owned newspapers with the Blantyre Newspapers Limited and Nations Publications Limited owning five and four titles respectively under each media house. The remaining four are community and religious publications. The dailies are The Nation and The Daily Times. Five (5) magazines, mostly religious (Source: www.osisa.org) Broadcasting in Malawi Types of licenses for broadcasting 1. Radio a) Public national Sound Broadcaster (State/ government owned) b) Private National Sound c) Community radio (Split into National community of interest, regional community of interest, geographical community sound) 2. Television a) Public National Television (State/government owned) b) Private National Television c) Community Of Interest Television 4 Radio Stations Malawi has 78 registered broadcast media and 43 are operational. -

Report of the Botswana Sadc Gender Protocol Summit and Awards

REPORT OF THE BOTSWANA SADC GENDER PROTOCOL SUMMIT AND AWARDS 26-27 MARCH 2013, BOIPUSO HALL, GABORONE, BOTSWANA Honorable Minister of Labour and Home Affairs Edwin Batshu with the winners of the Local Government Institutional and Climate Change and Sustainable Development award from Lobatse Town Council 1 CONTENTS Executive Summary 3 Participants 4 Background 4 Programme 4 Summit Outputs 5 Categories and Awards 6 Summit Outcomes 18 Lessons Learned 18 Next Steps 18 Annexes: ANNEX A – Participants list ANNEX B – Programme ANNEX C – Media Log ANNEX D – SWOT Analysis ANNEX E – Evaluation ANNEX F - Speeches 2 Executive summary QUICK FACTS: The Botswana SADC Protocol@work Summit brought together 180 participants, 53 men and 127 women from local government institutions, media, government and civil society organisations 50 entries were made by 39 women and 11 men, in 16 different categories Amongst the winning presenters were 14 women and 2 men The Summit was attended by, amongst others, representatives from the Ministry of Labour and Home Affairs, the Honourable Minister Edwin Batshu, 2 Deputy Permanent Secretaries and the Director of the Women’s Affairs Department Valencia Mogegeh, the Attorney General Athalia Molokomme and Head of the SADC Gender Unit, Magdeline Madibela 19 Local Councils were represented, amongst them Honourable Mayors, Councillors, Council Secretaries and staff. The summit also hosted non-governmental organisations, faith based organisations, representatives from the Botswana Police Stations amongst others 5 Media houses from the Centre’s of Excellence programme were represented The Botswana SADC Gender Protocol@work Summit was held from 26-27 March 2013 at the Boipuso Hall in Gaborone. -

ITU Case Study the Creation of the Botswana

ITU case study The creation of the Botswana Communications Regulatory Authority (BOCRA) 2014 BOCRA Case study _________________________________________________________________________________ The case study was prepared by Brian Goulden and Mandla Msimang of Pygma Consulting. The authors and the ITU wish to acknowledge and express their appreciation for the assistance provided by the Chief Executive, Mr Thari Pheko , and the staff of BOCRA in undertaking the research for this case study. The views expressed in this paper are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the ITU or its members. ©ITU 2014 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, by any means whatsoever, without the prior written permission of ITU. 2 BOCRA Case study _________________________________________________________________________________ 1. INTRODUCTION This case study is one of a series of short case studies conducted globally by the International Telecommunication Union (“ITU”) that reviews newly constituted or reorganised National Regulatory Authorities (“NRA”) where responsibilities have been expanded to encompass the broad spectrum of the communications sector. The aim of the case study is to highlight the experiences, challenges and solutions facing NRAs transitioning from operating in the narrower ICT sector to the wider national communications sector including the telecommunications, broadcasting, postal & courier services and operators. Botswana is a landlocked country surrounded by South Africa, Namibia, Zambia and Zimbabwe. In July 2013 it had an estimated population of 2’021’144million1, around 62% were urban dwellers in the capital city (Gaborone), other towns or large villages. It is ranked overall 74 in the 2014 Global Competitiveness Report published by the World Economic Forum. -

Service Broadcasters Or Government Mouthpieces – an Appraisal of Public Service Broadcasting in Botswana

Volume 10, Issue 1, April 2013 THE UNNECESSARY GRAVITY OF THE SOUL PUBLIC SERVICE BROADCASTERS OR GOVERNMENT MOUTHPIECES – AN APPRAISAL OF PUBLIC SERVICE BROADCASTING IN BOTSWANA Tachilisa Badala Balule* Abstract Public service broadcasting is a critical component of modern democratic societies. These broadcasters are expected to serve the general public interest by providing for the informational needs and interests of citizens in order to empower them to participate in public life. A public service broadcaster is therefore a national asset that must be independent of both political and commercial pressures in the performance of its mandate. The institution must never be used as a government mouthpiece whereby it will only serve the interests of the government of the day. A public service broadcaster thus requires a particular legal framework and certain structural attributes to enable it to execute its mandate effectively. This article examines public service broadcasting in Botswana and interrogates the question of whether or not the legal and policy framework in the country recognises this concept, and if so, whether or not the framework in place is appropriate for the effective delivery of a true public service broadcasting mandate. DOI: 10.2966/scrip.100113.77 © Tachilisa Badala Balule 2013. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Licence. Please click on the link to read the terms and conditions. * LLB (Botswana); LLM; PhD (Edinburgh). Senior Lecturer in Law, University of Botswana. (2013) 10:1 SCRIPTed 78 “The state media are national assets; they belong to the entire community, not to the abstraction known as the state nor to the government in office nor its party. -

Bocra Customer Satisfaction Survey

BOCRA CUSTOMER SATISFACTION SURVEY DRAFT FINAL REPORT PREPARED BY THE BOTSWANA INSTITUTE FOR DEVELOPMENT POLICY ANALYSIS (BIDPA) DATE OF SUBMISSION: 04/12/2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES ................................................................................................................................... v TABLE OF FIGURES ............................................................................................................................. vi LIST OF ACRONYMS .......................................................................................................................... vii FOREWORD ...................................................................................................................................... viii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................................................... ix FIXED LINES .................................................................................................................................... ix MOBILE SECTOR .............................................................................................................................. x INTERNET SECTOR ........................................................................................................................... x POSTAL SERVICES ........................................................................................................................... xi BROADCASTING SERVICES ........................................................................................................... -

Botswana Page 1 of 10

Botswana Page 1 of 10 Botswana Country Reports on Human Rights Practices - 2003 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor February 25, 2004 Botswana is a longstanding multiparty democracy. Constitutional power is shared between the President and a popularly elected National Assembly. Festus Mogae became President in 1998 and continued to lead the Botswana Democratic Party (BDP), which has held a majority of seats in the National Assembly continuously since independence. The 1999 elections generally were regarded as free and fair, despite initial restrictions on opposition access to radio and press reports of ruling party campaign finance improprieties. The Government generally respected the constitutional provisions for an independent judiciary. The civilian Government maintained effective control of the security forces. The Botswana Defense Force, which is under the control of the Defense Council within the Office of the President, has primary responsibility for external security, although it assisted with domestic law enforcement on a case-by-case basis. The Botswana National Police has primary responsibility for internal security. Some members of the security forces, in particular the police, occasionally committed human rights abuses. The economy of the country, which had a population of 1.7 million, was market-oriented with strong encouragement for private enterprise through tax benefits. Approximately 32 percent of the labor force worked in the informal sector, largely subsistence farming and animal husbandry. Rural poverty remained a serious problem, as did a widely skewed income distribution. Per capita gross domestic product decreased to $3,523 from $3,956 in 2001, according to the Bank of Botswana. -

ELECTION OBSERVER MISSION REPORT No 16 Order From: [email protected] EISA OBSERVER MISSION REPORT I

EISA ELECTION ELECTORAL OBSERVER REPORTS OBSERVER MISSION REPORT CODE TITLE EOR 1 Mauritius Election Observation Mission Report, 2000 EOR 2 SADC Election Support Network Observer Mission’s BOTSWANA Report, 1999/2000 EOR 3 Tanzania Elections Observer Mission Report, 2001 EOR 4 Tanzania Gender Observer Mission Report, 2001 EOR 5 Zimbabwe Elections Observer Mission Report, 2001 EOR 6 South African Elections Observer Mission Report, Denis Kadima, 1999 EOR 7 Botswana Elections Observer Mission Report, Denis Kadima, 1999 EOR 8 Namibia Elections Report, Tom Lodge, 1999 EOR 9 Mozambique Elections Observer Mission Report, Denis Kadima, 1999 EOR 10 National & Provincial Election Results: South Africa June 1999 EOR 11 Elections in Swaziland, S. Rule, 1998 EOR 12 Lesotho Election, S. Rule, 1998 EOR 13 EISA Observer Mission Report: Zimbabwe Presidential Election 9-11 March, 2002 (P/C) EOR 14 EISA Observer Mission Report: South Africa National and Provincial Elections 12-14 April 2004 PARLIAMENTARY AND EOR 15 EISA Observer Mission Report: Malawi Parliamentary LOCAL GOVERNMENT ELECTIONS and Presidential Elections 20 May 2004 30 OCTOBER 2004 ISBN 1-920095-12-8 9781920 095123 EISA ELECTION OBSERVER MISSION REPORT No 16 Order from: [email protected] EISA OBSERVER MISSION REPORT i EISA REGIONAL OBSERVER MISSION BOTSWANA PARLIAMENTARY AND LOCAL GOVERNMENT ELECTIONS 30 OCTOBER 2004 ii EISA OBSERVER MISSION REPORT EISA OBSERVER MISSION REPORT iii EISA REGIONAL OBSERVER MISSION BOTSWANA PARLIAMENTARY AND LOCAL GOVERNMENT ELECTIONS 30 OCTOBER 2004 2005 iv EISA OBSERVER MISSION REPORT Published by EISA 2nd Floor, The Atrium 41 Stanley Avenue, Auckland Park Johannesburg, South Africa 2196 P O Box 740 Auckland Park 2006 South Africa Tel: 27 11 482 5495 Fax: 27 11 482 6163 Email: [email protected] www.eisa.org.za ISBN: 1-920095-12-8 EISA 2005 All rights reserved. -

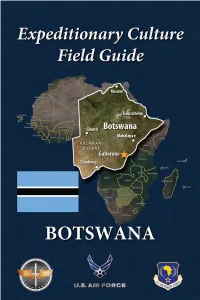

ECFG Botswana 2021R.Pdf

About this Guide This guide is designed to prepare you to deploy to culturally complex environments and achieve mission objectives. The fundamental information contained within will help you understand the cultural dimension of your assigned location and gain skills necessary for success. Botswana ECFG The guide consists of 2 parts: Part 1 introduces “Culture General,” the foundational knowledge you need to operate effectively in any global environment. Part 2 presents “Culture Specific” Botswana, focusing on unique cultural features of Botswana’s society and is designed to complement other pre- deployment training. It applies culture- general concepts to help increase your knowledge of your assigned location. For further information, visit the Air Force Culture and Language Center (AFCLC) website at www.airuniversity.af.edu/AFCLC/ or contact AFCLC’s Region Team at [email protected]. Disclaimer: All text is the property of the AFCLC and may not be modified by a change in title, content, or labeling. It may be reproduced in its current format with the expressed permission of the AFCLC. All photography is provided as a courtesy of the US government, Wikimedia, and other sources as indicated. GENERAL CULTURE CULTURE PART 1 – CULTURE GENERAL What is Culture? Fundamental to all aspects of human existence, culture shapes the way humans view life and functions as a tool we use to adapt to our social and physical environments. A culture is the sum of all of the beliefs, values, behaviors, and symbols that have meaning for a society. All human beings have culture, and individuals within a culture share a general set of beliefs and values. -

Botswana Neglected Tropical Diseases Master Plan 2015-2020 Ministry Of

Botswana Neglected Tropical Diseases Master Plan 2015-2020 BOTSWANA NEGLECTED TROPICAL DISEASES MASTER PLAN 2015-2020 MINISTRY OF HEALTH 1 Botswana Neglected Tropical Diseases Master Plan 2015-2020 CONTENTS ACRONYMS ......................................................................................................................................... 4 FOREWORD ........................................................................................................................................ 6 Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................ 8 PART 1: SITUATION ANALYSIS ................................................................................................ 9 1.1 COUNTRY PROFILE ........................................................................................................... 9 1.1.1 Administrative, Demographic and Community Structures .................................... 9 1.1.1.3 Social Organization of Communities ................................................................................. 12 1.1.2 Geographical Characteristics .................................................................................................. 13 1.1.3 Socio- Economic status and indicators ................................................................................. 14 1.1.4 Water and Sanitation .............................................................................................................. 14 1.1.5 Transport and -

Television in Botswana: Development and Policy Perspectives

Television in Botswana: Development and Policy Perspectives Seamogano Mosanako Master of Arts, Journalism (International), University of Westminster (London), 2004 Bachelor of Social Work, University of Botswana, 1996 A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2014 School of Journalism and Communication 1 Abstract Although numerous scholars across the world have sought to explore the relevance of television for development purposes in various national settings, there is a dearth of literature on the use of television for development in the Botswana context. A national television service, Botswana Television (Btv) was introduced in 2000 by the Botswana Government. However, Btv’s role in national development has received limited research attention. This study examines the role of television in national development in Botswana. In addition, the study explores the factors that influence the performance of television in a developing country context, with a view to suggest issues for consideration in media policy in Botswana to improve the performance of the Btv. This analysis of Btv was conducted through a qualitative research methodology that comprised document analysis, schedule analysis, in-depth interviews, and focus group discussions. This combination of methods provides data that contributes to a more holistic knowledge of media and development in Botswana. Various documents about Btv and media in Botswana were reviewed to establish the media policy issues relating to television broadcasting in Botswana. The schedule analysis, which was a unique method applied in this study, involved reviewing samples of Btv schedules from 2010 and 2011 to examine Btv’s program output, specifically, the content related to Botswana’s national development priorities. -

Promoting Language and Cultural Diversity Through the Mass Media: Views of Students at the University of Botswana

ISSN 2411-9563 (Print) European Journal of Social Sciences September-December 2015 ISSN 2312-8429 (Online) Education and Research Volume 2, Issue 4 Promoting Language and Cultural Diversity through the Mass Media: Views of Students at the University of Botswana Koketso Jeremiah Lecturer, Department of Languages and Social Sciences Education, University of Botswana [email protected] Abstract This study investigates the views of students at the University of Botswana as to whether or not the current situation in which the languages of ethnic minority groups in Botswana are marginalized or excluded for use in the national media such as television, radio and the Botswana Daily News, should continue or not. The study answered the following research questions: 1. What national television and radio stations exist in Botswana? 2. What programmes do these television and radio stations broadcast and with which languages? 3. Is the current situation of broadcasting with regard to the languages used for broadcasting fair, and, if not, what can be done to remedy the situation? It also addressed the following objectives:1. To identify the national television and radio stations which exist in Botswana? 2. To identify the programmes that the existing national television and radio stations broadcast and the languages used to broadcast those programmes. 3. To find out if the current system of broadcasting is fair in terms of the languages used and if it is not, to suggest some measures that can be taken to remedy the situation.The study used qualitative methods. Sampling was done by using purposive sampling. The data collection method used was a questionnaire.