Mobile Communication : Bringing Us Together and Tearing Us Apart / Rich Ling & Scott W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eric Clapton: Guitar Chord Songbook Songlist

Hal Leonard – Eric Clapton: Guitar Chord Songbook Songlist: Let It Grow Let It Rain Alberta Lonely Stranger All Your Love (I Miss Loving) Malted Milk Anyone For Tennis Mean Old World Baby What's Wrong Miss You Bad Love Motherless Children Badge My Father's Eyes Before You Accuse Me (Take A Look At Old Love Yourself) One More Chance Bell Bottom Blues Only You Know And I Know Better Make It Through Today Presence Of The Lord Born Under A Bad Sign Promises Change The World Ramblin' On My Mind Cocaine Riding With The King Comin' Home Roll It Over Crosscut Saw Running On Faith Cross Road Blues (Crossroads) San Francisco Bay Blues Evil (Is Going On) See What Love Can Do For Your Love The Shape You're In Got To Get Better In A Little While She's Waiting Hard Times Someone Like You Have You Ever Loved A Woman Spoonful Heaven Is One Step Away Strange Brew Hello Old Friend Sunshine Of Your Love Hey Hey Superman Inside Holy Mother Tales Of Brave Ulysses Honey In Your Hips Tearing Us Apart I Ain't Got You Tears In Heaven I Can't Stand It Tell The Truth I Feel Free Thorn Tree In The Garden I Shot The Sheriff Too Bad I Wish You Would Walkin' Blues I'm Tore Down Watch Out For Lucy It's In The Way That You Use It Whatcha Gonna Do Knockin' On Heaven's Door White Room Lawdy Mama Willie And The Hand Jive Lay Down Sally Wonderful Tonight Layla Wrapping Paper. -

Eric Clapton

ERIC CLAPTON BIOGRAFIA Eric Patrick Clapton nasceu em 30/03/1945 em Ripley, Inglaterra. Ganhou a sua primeira guitarra aos 13 anos e se interessou pelo Blues americano de artistas como Robert Johnson e Muddy Waters. Apelidado de Slowhand, é considerado um dos melhores guitarristas do mundo. O reconhecimento de Clapton só começou quando entrou no “Yardbirds”, banda inglesa de grande influência que teve o mérito de reunir três dos maiores guitarristas de todos os tempos em sua formação: Eric Clapton, Jeff Beck e Jimmy Page. Apesar do sucesso que o grupo fazia, Clapton não admitia abandonar o Blues e, em sua opinião, o Yardbirds estava seguindo uma direção muito pop. Sai do grupo em 1965, quando John Mayall o convida a juntar-se à sua banda, os “Blues Breakers”. Gravam o álbum “Blues Breakers with Eric Clapton”, mas o relacionamento com Mayall não era dos melhores e Clapton deixa o grupo pouco tempo depois. Em 1966, forma os “Cream” com o baixista Jack Bruce e o baterista Ginger Baker. Com a gravação de 4 álbuns (“Fresh Cream”, “Disraeli Gears”, “Wheels Of Fire” e “Goodbye”) e muitos shows em terras norte americanas, os Cream atingiram enorme sucesso e Eric Clapton já era tido como um dos melhores guitarristas da história. A banda separa-se no fim de 1968 devido ao distanciamento entre os membros. Neste mesmo ano, Clapton a convite de seu amigo George Harisson, toca na faixa “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” do White Album dos Beatles. Forma os “Blind Faith” em 1969 com Steve Winwood, Ginger Baker e Rick Grech, que durou por pouco tempo, lançando apenas um album. -

The 5 Second Rule: Transform Your Life, Work, and Confidence with Everyday Courage © 2017 by Mel Robbins All Rights Reserved

A SAVIO REPUBLIC BOOK The 5 Second Rule: Transform Your Life, Work, and Confidence with Everyday Courage © 2017 by Mel Robbins All Rights Reserved ISBN: 978-1-68261-238-5 ISBN (eBook): 978-1-68261-239-2 Cover Design by Rachel Greenberg Interior Composition by Greg Johnson/Textbook Perfect No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted by any means without the written permission of the author and publisher. Published in the United States of America Digital book(s) (epub and mobi) produced by Booknook.biz. THIS IS THE TRUE STORY OF THE 5 SECOND RULE WHAT it is, WHY it works, and HOW people around the world are using it to change their lives in five simple seconds. The events described in this book are real. No names have been changed. The social media posts that appear throughout this book are the actual posts. I cannot wait to share this book with you and watch you unlock the power of you. 5...4...3...2...1...GO! Xo, Mel THE 5 SECOND RULE TRANSFORM YOUR LIFE, WORK, AND CONFIDENCE WITH EVERYDAY COURAGE THE 5 SECOND RULE 1. Five Seconds To Change Your Life 2. How I Discovered the 5 Second Rule PART 1 3. What You Can Expect When You Use It 4. Why The Rule Works THE POWER OF COURAGE 5. Everyday Courage 6. What Are You Waiting For? PART 2 7. You’ll Never Feel Like It 8. How To Start Using the Rule COURAGE CHANGES YOUR BEHAVIOR How to Become the Most Productive Person You Know 9. -

Tech Fast Forward” Families Might Be Blazing New Trails for the Rest of Us

TECH Plug in to see the brighter side of life Despite relatively high life- “Is Technology Making Us “The Dumbest satisfaction numbers, 2 Gallup reported the Lonelier?” Generation: MEREdiTH MELNICK, TiME MAGAZINE, How the Digital Age lowest overall JANUARY 2011 Stupefies Young score Americans and since they began recording Jeopardizes Our Future* that data in 2001.1 (Or, Don’t Trust Anyone 3 GALLUP, WWW.GALLUP.COM, Under 30)” JANUARY 2011 MARK BAUERLEIN, PENGUIN, 2008 There is no doubt that technology is screaming along, changing our world one megabyte—no, make that terabyte—at a time. Our world has gone from 1G to 4G, from chalkboards to smartboards and from face time to Facebook in less than a decade, all with kids in the front seat of this white-knuckle ride. As exhilarating and promising as this technology rollercoaster may be, there is a lot of negative chatter and press about how our lives, our children, our future and our world are headed for total doom and destruction. “The Shallows: “Distracted: What the Internet is The Erosion of Attention and “iBrain: 4 Surviving the Technical Doing to our Brains” the Coming Dark Age,”5 NiCHOLAS CARR, W. W. NORTON Alteration of the Modern MAggiE JACKSON, PROMETHEUS & COMPANY, 2010 6 BOOKS, 2008 Mind.” GARY SMALL, M.D. AND Gigi VORGAN, HARPER, 2009 3 “Is the Internet Parents today spend “Your Brain on Computers: Destroying 40% less time Attached to with their Technology and Your Brain?” 9 Try This Test.7 children Paying a Price.” ANDREW PRICE, GOOD MAGAZINE, than 30 years ago.8 MATT RiCHTEL, WWW.NYTIMES.COM, JUNE 2007 JUNE 2010 IAN JUKES, TED MCCAIN & LEE CROCKETT, 21ST CENTURY FLUENCY PROJECT, 2010 Technology has become a popular scapegoat for many modern issues, blamed for the demise of the family, destruction of human relationships, erosion of our mental state, decline of our physical health, corruption of our values, deterioration of our intelligence and creativity and near obliteration of our safety and privacy. -

July/ August 2017 JULY/AUGUST 2017

July/ August 2017 JULY/AUGUST 2017 NEWSLETTER Dear Friends, was titled, “Where Do We Go From Here: Chaos or One of the real blessings of taking a holiday is the Community?” relief to the mind and the emotions of not getting One of his insights then was that a moment of crisis much news. You can’t avoid it completely, but there is is always a moment of decision. It was true then and a freedom when there are no TV pictures invading is true now. Where do we go from here? Chaos? your personal space. Part of you wants it to go on Indifference? Avoidance? Business as usual? Or forever. Settle down in a nice secluded part of Beloved Community?’ France with someone you love, surrounded by Curry then goes on to invite people to rededicate vineyards and acres of sunflowers, with wonderful themselves to the core work of Christian community food and delicious wine, a pile of highly – which is reconciliation. recommended novels and no timetable. I think this is hugely helpful. Things are too scary at Of course it’s not real life - even for the folk who the moment to think we can make any difference on live there, but we all need to create spaces where we our own, but within the context of our community feel safe and can love the beauty and the joy of the we can model a open, accepting and inclusive way of world. living that points to hope not fear. That is good and healthy, and it’s a world away from choosing to live your whole life with your head in the sand. -

Everywhere You Look by Tim Soerens

Taken from Everywhere You Look by Tim Soerens. Copyright © 2020 by Timothy Soerens. Published by InterVarsity Press, Downers Grove, IL. www.ivpress.com. CHAPTER ONE THE MOVEMENT OR THE MELTDOWN laudette Colvin doesn’t have any museums or hol- idays named after her, but she should. You’ve un- C doubtedly heard of Rosa Parks, the young woman who was ruthlessly dragged off a bus in Montgomery, Al- abama, for refusing to give her seat to a white person. What many people don’t know is that nine months earlier the same thing happened to Claudette. On March 15, 1955, on her way home from high school, fi fteen-year-old Claudette took a seat on a bus in Montgomery. When the bus driver told her to give her seat to a white person, she refused. Within minutes her books were fl ying in the air; two police offi cers put her in handcuff s and started to drag her off the bus. Without fi ghting back or cussing, she kept telling everyone who would listen that sitting on the bus was her constitutional right, but that didn’t keep her from ending up in the adult jail at the police 5 342102PZY_EVERYWHERE_CC2019_PC.indd 5 April 24, 2020 11:15 AM EVERYWHERE YOU LOOK station. While in lockup, she prayed the Lord’s Prayer and Psalm 23 over and over, all the while hoping her family and neighbors would somehow discover she was there. She hadn’t been given the opportunity to call anyone. Thankfully, her schoolmates who were also on the bus spread the word around the neighborhood. -

BREAK the RULES 50 Smashing Ways to Be More Creative

BREAK THE RULES 50 Smashing Ways To Be More Creative James Hegarty Smashwords Edition Copyright 2015 James Hegarty TheCreativeEdgeBooks.com Also by this author The Inspiration Notebook: Over 100 Ways to Begin Work of Art: The Craft of Creativity Guts & Soul: Looking for Street Music and Finding Inspiration To See: Tokyo Street Photography New York 1979 1980: Street Photography Lost and Found To the spirit of creativity in each of us __________ TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface: This we must do Part One: Discovery 1. Identity - the radical source of creativity Break the mold Go to the mountain 2. Vision - the soul of creativity Really big Finding sushi 3. Inspiration - the intersection of imagination and reality Take risks, cause collisions The legend of inspiration Part Two: Action 4. Voice - the content and form of ideas Crank it up Where it’s at Sample this 5. Process - the system of development and implementation This better work Make some beats Part Three: Freedom 6. Courage - the strength to succeed The comfort of uncertainty Time after time 7. Integrity – the foundation of freedom The real reason for everything A story of radical creativity Afterword: Standing on the edge A note of thanks Bibliography Preface __________ THIS WE MUST DO We are creative. All of us. Creativity is part of us. It is basic to who we are, what we do, and why we are here. And like any human activity, creativity can be developed and expanded. We all can learn to be more creative and to express our creativity more directly. I realize that might seem pretty radical, not least because a lot of people don’t believe it. -

January 2012 Nnaahhggaahhcchhiiwwaannoonngg (Far End of the Great Lake) Ddiibbaahhjjimimoowwiinnnnaann (Narrating of Story)

January 2012 NNaahhggaahhcchhiiwwaannoonngg (Far end of the Great Lake) DDiibbaahhjjimimoowwiinnnnaann (Narrating of Story) Goodbye to a friend and a leader 1720 BIG LAKE RD. Mary Northrup standing outside of the assisted living facility during the opening Presort Std party on July 29. Mary passed away this month and will always be remembered as a CLOQUET, MN 55720 U.S. Postage veteran, a leader, a friend. Photo by Dan Huculak. CHANGE SERVICE REQUESTED PAID Permit #155 Cloquet, MN 55720 In This Issue: Local news .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .2-3 RBC pages .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .4-5 More Local news .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .6-7 Etc .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .8-9 Law Enforcement .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 10 Area News. 11 Health. .12 13 Moons . .13 Community news .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 14-15 Page 2 | Nah gah chi wa nong • Di bah ji mowin nan | January 2012 Local news Remembering Mary By Dan Huculak Community College. Mary re- a great time and we traveled a ceived her Bachelor’s of Science total of 2,711 miles. We visited he Fond du Lac com- Degree in social work from the our brother and my son in munity was shocked and College of St. Scholastica. Wis., and the graveyard of our Tsaddened to learn that Northrup served on the Fond birth father in Indiana. We ate Brookston District Representa- du Lac Ojibwe School Board cupcakes every day and stopped tive Mary Northrup passed for 10 years, served as the FDL at fun roadside places like the away unexpectedly Dec. 6, just Veterans Service Officer and Vacuum Cleaner Museum.” one week before her was elected to serve The two sisters also attended 50th birthday. -

Picture Bright for Country V/Dc//Ps Ever -And a 1988 Holiday Season Bo- As Was the Case in the Early Days Nanza for MCA

Poison, Great White album art altered <i.ci<'A- .******,:c 4( c*a; DIGIT 908 after retail revolt 9AR OQHZ ' 000917973 4401, 8819 See page 8 MONTY GREENLY 'Whitney' hits another APT N 3740 ELM multiplatinum milestone LONG BE NCH CA 90807 See page 6 Getting ready for Atlantic's big bash See The Eye, page 61 I I R VOLUME 100 NO. 20 THE INTERNATIONAL NEWSWEEKLY OF MUSIC AND HOME ENTERTAINMENTr May 14, 1988/$3.95 (U.S.), $5 (CAN.) DAT- Duping Plants Sprout MCA Sets $24.95 List. Pepsi To Offer $5 Rebate In Hope Of Fertile Market `E.T.' Vid At Down -To -Earth Price heavily involved in real -time DAT MCA Inc. president Sidney Shein- price for "E.T." is considerably low- BY STEVEN DUPLER production was California -based BY CHRIS MORRIS berg and MCA Home Entertain- er than what was first anticipated. NEW YORK While mass -scale Loranger Manufacturing Corp., LOS ANGELES MCA Home Video ment Group president Gene In February, when MCA announced DAT duplication continues to await which is turning out small runs of will bring "E.T. -The Extra-Terres- Giaquinto trumpeted the home vid- the film's home video release, many both major -label acceptance of the DAT cassettes for German -based trial" home on videocassette Oct. 27 eo arrival of the 1982 Steven Spiel- industry pros assumed that MCA configuration and perfection of pro- classical label Capriccio Digital and at a suggested retail price of $24.95. berg-directed theatrical blockbuster would market the tape at $29.95 totype high -speed DAT duplicating its U.S. -

Wateraerobics Master by Song 2207 Songs, 5.9 Days, 16.35 GB

Page 1 of 64 wateraerobics master by song 2207 songs, 5.9 days, 16.35 GB Name Time Album Artist 1 Act Of Contrition 2:19 Like A Prayer Madonna 2 The Actress Hasn't Learned The… 2:32 Evita [Disc 2] Madonna, Antonio Banderas, Jo… 3 Addicted To Love 5:23 Tina Live In Europe Tina Turner 4 Addicted To Love (Glee Cast Ve… 3:59 Glee: The Music, Tested Glee Cast 5 Adiós, Pampa Mía! 3:08 Tango Julio Iglesias 6 Advice For The Young At Heart 4:55 The Seeds Of Love Tears For Fears 7 Affairs Of The Heart 3:47 Black Moon Emerson, Lake & Palmer 8 After Midnight 3:09 Time Pieces - The Best Of Eric… Eric Clapton 9 Afternoon Delight (Glee Cast Ve… 3:12 Afternoon Delight (Glee Cast Ve… Glee Cast 10 Against All Odds (Take A Look A… 4:14 Cardiomix The Chris Phillips Project 11 Ain't It A Shame 3:37 The Complete Collection And Th… Barry Manilow 12 Ain't It Heavy 4:25 Greatest Hits: The Road Less Tr… Melissa Etheridge 13 Ain't Looking For Love 4:41 Big Ones Loverboy 14 Ain't Nothing Like The Real Thing 2:17 Every Great Motown Hit of Marvi… Marvin Gaye 15 Ain't That Peculiar 3:02 Every Great Motown Hit of Marvi… Marvin Gaye 16 Air (Andante Religioso) from Hol… 6:53 an Evening with Friends Edvard Grieg - Sir Neville Marrin… 17 Alabama Song 3:20 Best Of The Doors [Disc 1] The Doors 18 Alcazar 7:29 Upfront David Sanborn 19 Alena (Jazz) 5:30 Nightowl Gregg Karukas 20 Alive 3:59 Best Of The Bee Gees, Vol. -

Tina Turner the Collected Recordings (Sixties to Nineties) Mp3, Flac, Wma

Tina Turner The Collected Recordings (Sixties To Nineties) mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Funk / Soul / Pop Album: The Collected Recordings (Sixties To Nineties) Country: Europe Released: 1994 Style: Funk, Soul, Pop Rock, Ballad MP3 version RAR size: 1304 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1374 mb WMA version RAR size: 1294 mb Rating: 4.4 Votes: 797 Other Formats: APE VQF AU MOD RA MMF WAV Tracklist Hide Credits Fool In Love 1-1 –Ike & Tina Turner 2:53 Written-By – Turner* It's Gonna Work Out Fine 1-2 –Ike & Tina Turner 3:03 Written-By – McCoy*, McKinney* I Idolize You 1-3 –Ike & Tina Turner 2:52 Written-By – Turner* Poor Fool 1-4 –Ike & Tina Turner 2:33 Written-By – Turner* A Letter From Tina 1-5 –Ike & Tina Turner 2:34 Written-By – Turner* Finger Poppin' 1-6 –Ike & Tina Turner 2:47 Written-By – Blackwell* River Deep Mountain High 1-7 –Ike & Tina Turner 3:39 Written-By – Spector, Greenwich & Barry Crazy 'Bout You Baby 1-8 –Ike & Tina Turner 3:26 Written-By – Williamson* I've Been Loving You Too Long 1-9 –Ike & Tina Turner 3:54 Written-By – Butler*, Blackwell* Bold Soul Sister 1-10 –Ike & Tina Turner 2:36 Written-By – Turner* I Want You To Take You Higher 1-11 –Ike & Tina Turner 2:54 Written-By – Stewart* Come Together 1-12 –Ike & Tina Turner 3:42 Written-By – Lennon, McCartney* Honky Tonk Woman 1-13 –Ike & Tina Turner 3:10 Written-By – Richard, Jagger* Proud Mary 1-14 –Ike & Tina Turner 4:59 Written-By – Fogerty* Nutbush City Limits 1-15 –Ike & Tina Turner 3:00 Written-By – Turner* Sexy Ida (Part I) 1-16 –Ike & Tina Turner 2:30 -

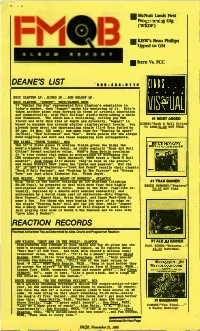

Deane's List Reaction Records

111 McNutt Lands First Programming Gig (WKDF) • KISW's Beau Phillips Upped to GM II Stern Vs. FCC DEANE'S LIST 6 0 9 - 4 2 4 - 9 1 1 4 ERIC CLAPTON LP...KINKS LP...BOB GELDOF LP. ERIC CLAPTON, "AUGUST", DUCK/WARNER BROS If "Behind The Sun" represented Eric Clapton's adaptation to today's market, then "August" marks his mastering of it. Eric's taken another giant step forward in terms of artistic innovation and commerciality, with Phil Collins' studio savvy adding a whole new dimension. The album has a rollicking, rolling pop R&B #1 MOST ADDED flavor and with this kind of depth and diversity, "August" is bound to surpass his already stellar airplay/retail levels. You KINKS/"Rock & Roll Cities already know about the chartmauling single (11-8 Trax fueled by 71 ADDS/D-40 HOT TRAX 20 ups, 24 Max, 125 cume); now make room for "Tearing Us Apart" (w/Tina), "Bad Influence" and "Run". Extra points for the always mind boggling axe work and those happening horn arrangements. THE KINKS, "THINK VISUAL", MCA The 12"'s first place 71 station finish gives the Kinks the week's highest #40 Trax debut, as radio exploits "Rock And Roll Cities" format exclusive value. WAAF's Russ Mottla proclaims it "a true rocker that makes no pretentions of screaming for CHR crossover status", Mark Chernoff, WNEW hears a "Rock'N Roll monster", Jack Green KLPX shouts "they're back in the groove", and Glenn Uiewart WHJY likes the "power and passion". But the 12" is just the beginning---"Lost And Found" recalls their classic "Rock N Roll Fantasy", and "Working At The Factory" and "Sleazy Town" are just plain Kinksize fun.