Fish Life in the Kelp Beds and the Effects of Kelp Harvesting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Field Guide to the Nonindigenous Marine Fishes of Florida

Field Guide to the Nonindigenous Marine Fishes of Florida Schofield, P. J., J. A. Morris, Jr. and L. Akins Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute endorsement or recommendation for their use by the United States goverment. Pamela J. Schofield, Ph.D. U.S. Geological Survey Florida Integrated Science Center 7920 NW 71st Street Gainesville, FL 32653 [email protected] James A. Morris, Jr., Ph.D. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration National Ocean Service National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science Center for Coastal Fisheries and Habitat Research 101 Pivers Island Road Beaufort, NC 28516 [email protected] Lad Akins Reef Environmental Education Foundation (REEF) 98300 Overseas Highway Key Largo, FL 33037 [email protected] Suggested Citation: Schofield, P. J., J. A. Morris, Jr. and L. Akins. 2009. Field Guide to Nonindigenous Marine Fishes of Florida. NOAA Technical Memorandum NOS NCCOS 92. Field Guide to Nonindigenous Marine Fishes of Florida Pamela J. Schofield, Ph.D. James A. Morris, Jr., Ph.D. Lad Akins NOAA, National Ocean Service National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science NOAA Technical Memorandum NOS NCCOS 92. September 2009 United States Department of National Oceanic and National Ocean Service Commerce Atmospheric Administration Gary F. Locke Jane Lubchenco John H. Dunnigan Secretary Administrator Assistant Administrator Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................ i Methods .....................................................................................................ii -

Recommendations for Recreational Fisheries Contents Executive Summary 3 Introduction 5

PHAROS4MPAS SAFEGUARDING MARINE PROTECTED AREAS IN THE GROWING MEDITERRANEAN BLUE ECONOMY RECOMMENDATIONS FOR RECREATIONAL FISHERIES CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 INTRODUCTION 5 PART ONE BACKGROUND INFORMATION: RECREATIONAL FISHERIES 7 Front cover: Catching a greater amberjack (Seriola dumerili) 1.1. Definition of recreational fisheries in the Mediterranean 9 from a big game fishing boat © Bulentevren / Shutterstock 1.2. Importance of recreational fisheries in Europe and the Mediterranean 10 1.3. The complexity of recreational fisheries in the Mediterranean 13 Publication We would like to warmly thank all the people and organizations who were part of the advisory group of Published in July 2019 by PHAROS4MPAs. this publication or kindly contributed in some other PART TWO © PHAROS4MPAs. All rights reserved way: Fabio Grati (Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche - ISMAR), Reproduction of this publication for educational or other Antigoni Foutsi, Panagiota Maragou and Michalis Margaritis RECREATIONAL FISHERIES: INTERACTIONS WITH MARINE PROTECTED AREAS 15 non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written (WWF-Greece), Victoria Riera (Generalitat de Catalunya), Marta permission from the copyright holder provided the source is Cavallé (Life Platform), Jan Kappel (European Anglers Alliance), PART THREE fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale Anthony Mastitski (University of Miami), Sylvain Petit (PAP/ or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written RAC), Robert Turk (Institute of the Republic of Slovenia for Nature BENEFITS AND IMPACTS OF RECREATIONAL FISHERIES 21 permission of the copyright holder. Conservation), Paco Melia (Politechnica Milano), Souha El Asmi and Saba Guellouz (SPA/RAC), Davide Strangis and Lise Guennal 3.1. Social benefits and impacts 22 Citation of this report: Gómez, S., Carreño, A., Sánchez, (CRPM), Marie Romani, Susan Gallon and Wissem Seddik E., Martínez, E., Lloret, J. -

Qt9z7703dj.Pdf

UC San Diego UC San Diego Previously Published Works Title Phylogeny and biogeography of a shallow water fish clade (Teleostei: Blenniiformes) Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9z7703dj Journal BMC Evolutionary Biology, 13(1) ISSN 1471-2148 Authors Lin, Hsiu-Chin Hastings, Philip A Publication Date 2013-09-25 DOI http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2148-13-210 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Lin and Hastings BMC Evolutionary Biology 2013, 13:210 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2148/13/210 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Phylogeny and biogeography of a shallow water fish clade (Teleostei: Blenniiformes) Hsiu-Chin Lin1,2* and Philip A Hastings1 Abstract Background: The Blenniiformes comprises six families, 151 genera and nearly 900 species of small teleost fishes closely associated with coastal benthic habitats. They provide an unparalleled opportunity for studying marine biogeography because they include the globally distributed families Tripterygiidae (triplefin blennies) and Blenniidae (combtooth blennies), the temperate Clinidae (kelp blennies), and three largely Neotropical families (Labrisomidae, Chaenopsidae, and Dactyloscopidae). However, interpretation of these distributional patterns has been hindered by largely unresolved inter-familial relationships and the lack of evidence of monophyly of the Labrisomidae. Results: We explored the phylogenetic relationships of the Blenniiformes based on one mitochondrial (COI) and four nuclear (TMO-4C4, RAG1, Rhodopsin, and Histone H3) loci for 150 blenniiform species, and representative outgroups (Gobiesocidae, Opistognathidae and Grammatidae). According to the consensus of Bayesian Inference, Maximum Likelihood, and Maximum Parsimony analyses, the monophyly of the Blenniiformes and the Tripterygiidae, Blenniidae, Clinidae, and Dactyloscopidae is supported. -

Anthopleura and the Phylogeny of Actinioidea (Cnidaria: Anthozoa: Actiniaria)

Org Divers Evol (2017) 17:545–564 DOI 10.1007/s13127-017-0326-6 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Anthopleura and the phylogeny of Actinioidea (Cnidaria: Anthozoa: Actiniaria) M. Daly1 & L. M. Crowley2 & P. Larson1 & E. Rodríguez2 & E. Heestand Saucier1,3 & D. G. Fautin4 Received: 29 November 2016 /Accepted: 2 March 2017 /Published online: 27 April 2017 # Gesellschaft für Biologische Systematik 2017 Abstract Members of the sea anemone genus Anthopleura by the discovery that acrorhagi and verrucae are are familiar constituents of rocky intertidal communities. pleisiomorphic for the subset of Actinioidea studied. Despite its familiarity and the number of studies that use its members to understand ecological or biological phe- Keywords Anthopleura . Actinioidea . Cnidaria . Verrucae . nomena, the diversity and phylogeny of this group are poor- Acrorhagi . Pseudoacrorhagi . Atomized coding ly understood. Many of the taxonomic and phylogenetic problems stem from problems with the documentation and interpretation of acrorhagi and verrucae, the two features Anthopleura Duchassaing de Fonbressin and Michelotti, 1860 that are used to recognize members of Anthopleura.These (Cnidaria: Anthozoa: Actiniaria: Actiniidae) is one of the most anatomical features have a broad distribution within the familiar and well-known genera of sea anemones. Its members superfamily Actinioidea, and their occurrence and exclu- are found in both temperate and tropical rocky intertidal hab- sivity are not clear. We use DNA sequences from the nu- itats and are abundant and species-rich when present (e.g., cleus and mitochondrion and cladistic analysis of verrucae Stephenson 1935; Stephenson and Stephenson 1972; and acrorhagi to test the monophyly of Anthopleura and to England 1992; Pearse and Francis 2000). -

CHECKLIST and BIOGEOGRAPHY of FISHES from GUADALUPE ISLAND, WESTERN MEXICO Héctor Reyes-Bonilla, Arturo Ayala-Bocos, Luis E

ReyeS-BONIllA eT Al: CheCklIST AND BIOgeOgRAphy Of fISheS fROm gUADAlUpe ISlAND CalCOfI Rep., Vol. 51, 2010 CHECKLIST AND BIOGEOGRAPHY OF FISHES FROM GUADALUPE ISLAND, WESTERN MEXICO Héctor REyES-BONILLA, Arturo AyALA-BOCOS, LUIS E. Calderon-AGUILERA SAúL GONzáLEz-Romero, ISRAEL SáNCHEz-ALCántara Centro de Investigación Científica y de Educación Superior de Ensenada AND MARIANA Walther MENDOzA Carretera Tijuana - Ensenada # 3918, zona Playitas, C.P. 22860 Universidad Autónoma de Baja California Sur Ensenada, B.C., México Departamento de Biología Marina Tel: +52 646 1750500, ext. 25257; Fax: +52 646 Apartado postal 19-B, CP 23080 [email protected] La Paz, B.C.S., México. Tel: (612) 123-8800, ext. 4160; Fax: (612) 123-8819 NADIA C. Olivares-BAñUELOS [email protected] Reserva de la Biosfera Isla Guadalupe Comisión Nacional de áreas Naturales Protegidas yULIANA R. BEDOLLA-GUzMáN AND Avenida del Puerto 375, local 30 Arturo RAMíREz-VALDEz Fraccionamiento Playas de Ensenada, C.P. 22880 Universidad Autónoma de Baja California Ensenada, B.C., México Facultad de Ciencias Marinas, Instituto de Investigaciones Oceanológicas Universidad Autónoma de Baja California, Carr. Tijuana-Ensenada km. 107, Apartado postal 453, C.P. 22890 Ensenada, B.C., México ABSTRACT recognized the biological and ecological significance of Guadalupe Island, off Baja California, México, is Guadalupe Island, and declared it a Biosphere Reserve an important fishing area which also harbors high (SEMARNAT 2005). marine biodiversity. Based on field data, literature Guadalupe Island is isolated, far away from the main- reviews, and scientific collection records, we pres- land and has limited logistic facilities to conduct scien- ent a comprehensive checklist of the local fish fauna, tific studies. -

Marine Invertebrate Field Guide

Marine Invertebrate Field Guide Contents ANEMONES ....................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 AGGREGATING ANEMONE (ANTHOPLEURA ELEGANTISSIMA) ............................................................................................................................... 2 BROODING ANEMONE (EPIACTIS PROLIFERA) ................................................................................................................................................... 2 CHRISTMAS ANEMONE (URTICINA CRASSICORNIS) ............................................................................................................................................ 3 PLUMOSE ANEMONE (METRIDIUM SENILE) ..................................................................................................................................................... 3 BARNACLES ....................................................................................................................................................................................... 4 ACORN BARNACLE (BALANUS GLANDULA) ....................................................................................................................................................... 4 HAYSTACK BARNACLE (SEMIBALANUS CARIOSUS) .............................................................................................................................................. 4 CHITONS ........................................................................................................................................................................................... -

ASSESSMENT of COASTAL WATER RESOURCES and WATERSHED CONDITIONS at CHANNEL ISLANDS NATIONAL PARK, CALIFORNIA Dr. Diana L. Engle

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Technical Report NPS/NRWRD/NRTR-2006/354 Water Resources Division Natural Resource Program Centerent of the Interior ASSESSMENT OF COASTAL WATER RESOURCES AND WATERSHED CONDITIONS AT CHANNEL ISLANDS NATIONAL PARK, CALIFORNIA Dr. Diana L. Engle The National Park Service Water Resources Division is responsible for providing water resources management policy and guidelines, planning, technical assistance, training, and operational support to units of the National Park System. Program areas include water rights, water resources planning, marine resource management, regulatory guidance and review, hydrology, water quality, watershed management, watershed studies, and aquatic ecology. Technical Reports The National Park Service disseminates the results of biological, physical, and social research through the Natural Resources Technical Report Series. Natural resources inventories and monitoring activities, scientific literature reviews, bibliographies, and proceedings of technical workshops and conferences are also disseminated through this series. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute endorsement or recommendation for use by the National Park Service. Copies of this report are available from the following: National Park Service (970) 225-3500 Water Resources Division 1201 Oak Ridge Drive, Suite 250 Fort Collins, CO 80525 National Park Service (303) 969-2130 Technical Information Center Denver Service Center P.O. Box 25287 Denver, CO 80225-0287 Cover photos: Top Left: Santa Cruz, Kristen Keteles Top Right: Brown Pelican, NPS photo Bottom Left: Red Abalone, NPS photo Bottom Left: Santa Rosa, Kristen Keteles Bottom Middle: Anacapa, Kristen Keteles Assessment of Coastal Water Resources and Watershed Conditions at Channel Islands National Park, California Dr. Diana L. -

Cleaning Symbiosis Among California Inshore Fishes

CLEANING SYMBIOSIS AMONG CALIFORNIA INSHORE FISHES EDMUNDS. HOBSON' ABSTRACT Cleaning symbiosis among shore fishes was studied during 1968 and 1969 in southern California, with work centered at La Jolla. Three species are habitual cleaners: the seAoriF, Ozyjulis californica; the sharpnose seaperch, Phanerodon atripes; and the kelp perch, Brachyistius frenatus. Because of specific differences in habitat, there is little overlap in the cleaning areas of these three spe- cies. Except for juvenile sharpnose seaperch, cleaning is of secondary significance to these species, even though it may be of major significance to certain individuals. The tendency to clean varies between in- dividuals. Principal prey of most members of these species are free-living organisms picked from a substrate and from midwater-a mode of feeding that favors adaptations suited to cleaning. Because it is exceedingly abundant in a variety of habitats, the seiiorita is the predominant inshore cleaning fish in California. Certain aspects of its cleaning relate to the fact that only a few of the many seiioritas present at a given time will clean, and that this activity is not centered around well-defined cleaning stations, as has been reported for certain cleaning fishes elsewhere. Probably because cleaners are difficult to recognize among the many seiioritas that do not clean, other fishes.generally do not at- tempt to initiate-cleaning; rather, the activity is consistently initiated by the cleaner itself. An infest- ed fish approached by a cleaner generally drifts into an unusual attitude that advertises the temporary existence of the transient cleaning station to other fish in need of service, and these converge on the cleaner. -

Amphibious Fishes: Terrestrial Locomotion, Performance, Orientation, and Behaviors from an Applied Perspective by Noah R

AMPHIBIOUS FISHES: TERRESTRIAL LOCOMOTION, PERFORMANCE, ORIENTATION, AND BEHAVIORS FROM AN APPLIED PERSPECTIVE BY NOAH R. BRESSMAN A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of WAKE FOREST UNIVESITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Biology May 2020 Winston-Salem, North Carolina Approved By: Miriam A. Ashley-Ross, Ph.D., Advisor Alice C. Gibb, Ph.D., Chair T. Michael Anderson, Ph.D. Bill Conner, Ph.D. Glen Mars, Ph.D. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my adviser Dr. Miriam Ashley-Ross for mentoring me and providing all of her support throughout my doctoral program. I would also like to thank the rest of my committee – Drs. T. Michael Anderson, Glen Marrs, Alice Gibb, and Bill Conner – for teaching me new skills and supporting me along the way. My dissertation research would not have been possible without the help of my collaborators, Drs. Jeff Hill, Joe Love, and Ben Perlman. Additionally, I am very appreciative of the many undergraduate and high school students who helped me collect and analyze data – Mark Simms, Tyler King, Caroline Horne, John Crumpler, John S. Gallen, Emily Lovern, Samir Lalani, Rob Sheppard, Cal Morrison, Imoh Udoh, Harrison McCamy, Laura Miron, and Amaya Pitts. I would like to thank my fellow graduate student labmates – Francesca Giammona, Dan O’Donnell, MC Regan, and Christine Vega – for their support and helping me flesh out ideas. I am appreciative of Dr. Ryan Earley, Dr. Bruce Turner, Allison Durland Donahou, Mary Groves, Tim Groves, Maryland Department of Natural Resources, UF Tropical Aquaculture Lab for providing fish, animal care, and lab space throughout my doctoral research. -

List of Species Likely to Benefit from Marine Protected Areas in The

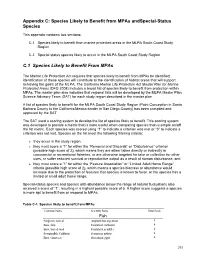

Appendix C: Species Likely to Benefit from MPAs andSpecial-Status Species This appendix contains two sections: C.1 Species likely to benefit from marine protected areas in the MLPA South Coast Study Region C.2 Special status species likely to occur in the MLPA South Coast Study Region C.1 Species Likely to Benefit From MPAs The Marine Life Protection Act requires that species likely to benefit from MPAs be identified; identification of these species will contribute to the identification of habitat areas that will support achieving the goals of the MLPA. The California Marine Life Protection Act Master Plan for Marine Protected Areas (DFG 2008) includes a broad list of species likely to benefit from protection within MPAs. The master plan also indicates that regional lists will be developed by the MLPA Master Plan Science Advisory Team (SAT) for each study region described in the master plan. A list of species likely to benefit for the MLPA South Coast Study Region (Point Conception in Santa Barbara County to the California/Mexico border in San Diego County) has been compiled and approved by the SAT. The SAT used a scoring system to develop the list of species likely to benefit. This scoring system was developed to provide a metric that is more useful when comparing species than a simple on/off the list metric. Each species was scored using “1” to indicate a criterion was met or “0” to indicate a criterion was not met. Species on the list meet the following filtering criteria: they occur in the study region, they must score a “1” for either -

Percomorph Phylogeny: a Survey of Acanthomorphs and a New Proposal

BULLETIN OF MARINE SCIENCE, 52(1): 554-626, 1993 PERCOMORPH PHYLOGENY: A SURVEY OF ACANTHOMORPHS AND A NEW PROPOSAL G. David Johnson and Colin Patterson ABSTRACT The interrelationships of acanthomorph fishes are reviewed. We recognize seven mono- phyletic terminal taxa among acanthomorphs: Lampridiformes, Polymixiiformes, Paracan- thopterygii, Stephanoberyciformes, Beryciformes, Zeiformes, and a new taxon named Smeg- mamorpha. The Percomorpha, as currently constituted, are polyphyletic, and the Perciformes are probably paraphyletic. The smegmamorphs comprise five subgroups: Synbranchiformes (Synbranchoidei and Mastacembeloidei), Mugilomorpha (Mugiloidei), Elassomatidae (Elas- soma), Gasterosteiformes, and Atherinomorpha. Monophyly of Lampridiformes is justified elsewhere; we have found no new characters to substantiate the monophyly of Polymixi- iformes (which is not in doubt) or Paracanthopterygii. Stephanoberyciformes uniquely share a modification of the extrascapular, and Beryciformes a modification of the anterior part of the supraorbital and infraorbital sensory canals, here named Jakubowski's organ. Our Zei- formes excludes the Caproidae, and characters are proposed to justify the monophyly of the group in that restricted sense. The Smegmamorpha are thought to be monophyletic principally because of the configuration of the first vertebra and its intermuscular bone. Within the Smegmamorpha, the Atherinomorpha and Mugilomorpha are shown to be monophyletic elsewhere. Our Gasterosteiformes includes the syngnathoids and the Pegasiformes -

Appendix 1. Bodega Marine Lab Student Reports on Polychaete Biology

Appendix 1. Bodega Marine Lab student reports on polychaete biology. Species names in reports were assigned to currently accepted names. Thus, Ackerman (1976) reported Eupolymnia crescentis, which was recorded as Eupolymnia heterobranchia in spreadsheets of current species (spreadsheets 2-5). Ackerman, Peter. 1976. The influence of substrate upon the importance of tentacular regeneration in the terebellid polychaete EUPOLYMNIA CRESCENTIS with reference to another terebellid polychaete NEOAMPHITRITE ROBUSTA in regard to its respiratory response. Student Report, Bodega Marine Lab, Library. IDS 100 ∗ Eupolymnia heterobranchia (Johnson, 1901) reported as Eupolymnia crescentis Chamberlin, 1919 changed per Lights 2007. Alex, Dan. 1972. A settling survey of Mason's Marina. Student Report, Bodega Marine Lab, Library. Zoology 157 Alexander, David. 1976. Effects of temperature and other factors on the distribution of LUMBRINERIS ZONATA in the substratum (Annelida: polychaeta). Student Report, Bodega Marine Lab, Library. IDS 100 Amrein, Yost. 1949. The holdfast fauna of MACROSYSTIS INTEGRIFOLIA. Student Report, Bodega Marine Lab, Library. Zoology 112 ∗ Platynereis bicanaliculata (Baird, 1863) reported as Platynereis agassizi Okuda & Yamada, 1954. Changed per Lights 1954 (2nd edition). ∗ Naineris dendritica (Kinberg, 1867) reported as Nanereis laevigata (Grube, 1855) (should be: Naineris laevigata). N. laevigata not in Hartman 1969 or Lights 2007. N. dendritica taken as synonymous with N. laevigata. ∗ Hydroides uncinatus Fauvel, 1927 correct per I.T.I.S. although Hartman 1969 reports Hydroides changing to Eupomatus. Lights 2007 has changed Eupomatus to Hydroides. ∗ Dorvillea moniloceras (Moore, 1909) reported as Stauronereis moniloceras (Moore, 1909). (Stauronereis to Dorvillea per Hartman 1968). ∗ Amrein reported Stylarioides flabellata, which was not recognized by Hartman 1969, Lights 2007 or the Integrated Taxonomic Information System (I.T.I.S.).