Is the Bank Merger Wave of the 1990S Efficient?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

U.S. Bancorp 2009 Annual Report U.S. B Anco Rp 20 09 a Nn Ua L Re

(1,1) -1- 090314 USB_09AR_cover.indd 2/25/10 3:34:19 PM Quality Strength Leadership U.S. Bancorp U. S. B anco rp 2009 20 09 Annual Report Annual A nn ua l Re po rt 090314 USB_09AR_cover.indd 1 22/25/10/25/10 33:34:18:34:18 PPMM (1,1) -2- 090314 USB_09AR_cover.indd 2/25/10 3:34:47 PM U.S. Bancorp At A Glance Corporate I Ranking U.S. Bank is 5th largest U.S. commercial bank Asset size $281 billion Executive Offi ces U.S. Bancorp Deposits $183 billion 800 Nicollet Mall Loans $195 billion Minneapolis, MN 55 Customers 17.2 million Payment services and merchant processing International Common Stock T and Registrar Wholesale banking and trust services National BNY Mellon Shareow Consumer and business banking our transfer agent a and wealth management Regional paying agent and di Bank branches 3,002 plan administrator, a shareholder records ATMs 5,148 Inquiries related to s NYSE symbol USB stock transfers, cha At year-end December 31, 2009 lost stock certificate and dividend payme to the transfer agent Sustainability Corporate Profi le BNY Mellon Shareow P.O. Box 358015 This annual report was printed at U.S. Bancorp is a diversified financial services Pittsburgh, PA 1525 Hennegan, a company committed Phone: 888-778-13 to sustaining a healthy and safe holding company and the parent company of 201-680-6578 (inter environment by exceeding regulatory Internet: bnymellon. and environmental requirements as U.S. Bank National Association, the fi fth-largest defi ned by local, state and federal commercial bank in the United States. -

H.2 Actions of the Board, Its Staff, and The

ANNOUNCEMENT H.2, 1993, No. 48 Actions of the Board, its Staff, and BOARD OF GOVERNORS the Federal Reserve Banks; OF THE Applications and Reports Received FEDERAL RESERVE SYSTEM During the Week Ending November 27, 1993 ACTIONS TAKEN BY THE BOARD OF GOVERNORS BANK HOLDING COMPANIFg Chemical Banking Corporation, New York, New York -- to engage in underwriting and dealing in, to a limited extent, all types of bank-ineligible equity securities through Chemical Securities Inc. Approved, November 24, 1993. Chemical Banking Corporation, New York, New York -- request for subsidiary banks and broker dealer subsidiaries of those banks to act as a riskless principal or broker for customers in buying and selling bank-eligible securities that Chemical*s section 20 subsidiary deals in or underwrites. Approved, November 24, 1993. First Alabama Bancshares, Inc., Birmingham, Alabama - - to acquire Secor Bank, F.S.B. Approved, November 22, 1993. BANK MERGERS First Alabama Bank, Birmingham, Alabama — to acquire certain assets and assume certain liabilities of Secor Bank, F.S.B. Approved, November 22, 1993. BOARD OPERATIONS Budget for 1994. Approved, November 24, 1993. Office of Inspector General -- budget for 1994. Approved, November 24, 1993. ENFORCEMENT Farmers and Merchants BanK or Long Deacn, Long Beach, California -- written agreement dated November 10, 1993, with the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco. Announced, November 22, 1993. First Tampa Bancorporation of Florida, Inc., Tampa, Florida -- written agreement dated November 8, 1993, with the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta. Announced, November 22, 1993. Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis H.2 NOVEMBER 22, 1993 TO NOVEMBER 26, 1993 PAGE 2 ACTIONS TAKEN BY THE BOARD OF GOVERNORS REGULATIONS AND POLICIES Regulation DD, Truth in Savings -- proposed changes concerning calculation of the annual percentage yields for certain deposits (Docket R-0812). -

Federal Register/Vol. 63, No. 164/Tuesday, August 25, 1998/Notices

Federal Register / Vol. 63, No. 164 / Tuesday, August 25, 1998 / Notices 45247 indicated. The application also will be and thereby engage in making and or the offices of the Board of Governors available for inspection at the offices of servicing loans, pursuant to § not later than September 8, 1998. the Board of Governors. Interested 225.28(b)(1) of Regulation Y; Money A. Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago persons may express their views in Station, Inc., Columbus, Ohio, and (Philip Jackson, Applications Officer) writing on the standards enumerated in thereby engage in data processing, 230 South LaSalle Street, Chicago, the BHC Act (12 U.S.C. 1842(c)). If the pursuant to § 225.28(b)(14)(i) of Illinois 60690-1413: proposal also involves the acquisition of Regulation Y; and DJJ Leasing Limited, a nonbanking company, the review also Cincinnati, Ohio, and thereby engage in 1. Advance Bancorp, Inc., includes whether the acquisition of the leasing personal or real property, Homewood, Illinois to engage de novo nonbanking company complies with the pursuant to § 225.28(b)(4) of Regulation through its subsidiary, Advance standards in section 4 of the BHC Act. Y. Applicant also applied to acquire an Bancorp, Inc., Homewood, Illinois, in Unless otherwise noted, nonbanking option to acquire 19.9 percent of Star extending credit and servicing loans, activities will be conducted throughout Banc Corporation. pursuant to § 225.28(b)(1) of Regulation the United States. Star Banc Corporation, Cincinnati, Y. Unless otherwise noted, comments Ohio, also has applied to acquire 19.9 Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve regarding each of these applications percent of the voting shares of Firstar System, August 19, 1998. -

Corporate Decision #97-36 June 1997

Comptroller of the Currency Administrator of National Banks Washington, D.C. 20219 Corporate Decision #97-36 June 1997 DECISION OF THE OFFICE OF THE COMPTROLLER OF THE CURRENCY ON THE APPLICATION TO MERGE COLORADO NATIONAL BANK, DENVER, COLORADO, COLORADO NATIONAL BANK ASPEN, ASPEN, COLORADO, FIRST BANK NATIONAL ASSOCIATION, CHICAGO, ILLINOIS, FIRST BANK NATIONAL ASSOCIATION, OMAHA, NEBRASKA, FIRST BANK OF SOUTH DAKOTA (NATIONAL ASSOCIATION), SIOUX FALLS, SOUTH DAKOTA, FIRST BANK (NATIONAL ASSOCIATION), MILWAUKEE, WISCONSIN, FIRST INTERIM BANK OF DES MOINES, N.A., DES MOINES, IOWA, AND FIRST INTERIM BANK OF CASPER, N.A., CASPER, WYOMING, WITH AND INTO FIRST BANK NATIONAL ASSOCIATION, MINNEAPOLIS, MINNESOTA June 1, 1997 ___________________________________________________________________________ __ I. INTRODUCTION On March 17, 1997, First Bank National Association, Minneapolis, Minnesota ("FBNA") filed an Application with the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency ("OCC") for approval to merge affiliated national banks located in other states into FBNA under FBNA’s charter and title, pursuant to 12 U.S.C. §§ 215a-1, 1828(c) & 1831u(a) (the "Merger Application"). The merger is structured as a single merger transaction with multiple affiliated target institutions. The affiliated banks are: Colorado National Bank, Denver, Colorado ("Colorado NB"), Colorado National Bank Aspen, Aspen, Colorado ("Aspen NB"), First Bank National Association, Chicago, Illinois ("FB Chicago"), First Bank National Association, Omaha, Nebraska ("FB Omaha"), First Bank of South Dakota (National Association), Sioux Falls, South Dakota ("FB South Dakota"), First Bank (National Association), Milwaukee, Wisconsin ("FB Milwaukee"), First Interim Bank of Des Moines, National Association, Des Moines, Iowa ("FB Des Moines"), and First Interim Bank of Casper, National Association, Casper, Wyoming ("FB Casper"). -

U.S. Bancorp (USB)

Strategic Report for U.S. Bancorp Ah Sung Yang Karen Bonner Andrew Dialynas April 14, 2010 US Bancorp Table of Contents Executive Summary ....................................................................................................... 3 Company Overview ........................................................................................................ 5 Company History ................................................................................................... 5 Business Model ..................................................................................................... 8 Competitive analysis .................................................................................................... 10 Industry Overview ................................................................................................ 10 Porter’s Five Forces Analysis .............................................................................. 11 Competitive Rivalry......................................................................................... 11 Entry and Exit ................................................................................................. 12 Supplier Power ............................................................................................... 13 Buyer power ................................................................................................... 14 Substitutes and Complements ........................................................................ 15 Financial Analysis ....................................................................................................... -

Federal Register / Vol. 60, No. 227 / Monday, November 27, 1995 / Notices 58363

Federal Register / Vol. 60, No. 227 / Monday, November 27, 1995 / Notices 58363 Y (12 CFR 225.21(a)) to commence or to 2. Progressive Growth Corp., Gaylord, company or to acquire voting securities engage de novo, either directly or Minnesota; to engage de novo through of a bank or bank holding company. The through a subsidiary, in a nonbanking its subsidiary, Progressive Technologies, listed companies have also applied activity that is listed in § 225.25 of Inc., Gaylord Minnesota, in data under § 225.23(a)(2) of Regulation Y (12 Regulation Y as closely related to warehousing, computer network CFR 225.23(a)(2)) for the Board's banking and permissible for bank integration services, communications approval under section 4(c)(8) of the holding companies. Unless otherwise services related to the transmission of Bank Holding Company Act (12 U.S.C. noted, such activities will be conducted economic and financial data, database 1843(c)(8)) and § 225.21(a) of Regulation throughout the United States. management services, and other data Y (12 CFR 225.21(a)) to acquire or Each application is available for processing services, pursuant to § control voting securities or assets of a immediate inspection at the Federal 225.25(b)(7) of the Board's Regulation Y. company engaged in a nonbanking Reserve Bank indicated. Once the C. Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas activity that is listed in § 225.25 of application has been accepted for City (John E. Yorke, Senior Vice Regulation Y as closely related to processing, it will also be available for President) 925 Grand Avenue, Kansas banking and permissible for bank inspection at the offices of the Board of City, Missouri 64198: holding companies, or to engage in such Governors. -

H.2 Actions of the Board, Its Staff, and The

ANNOUNCEMENT H.2, 1988, No. 29 Actions of the Board, its Staff, and BOARD OF GOVERNORS the Federal Reserve Banks; OF THE Applications and Reports Received FEDERAL RESERVE SYSTEM During the Week Ending July 16, 1988. ACTIONS TAKEN BY THE BOARD OF GOVERNORS ADVISORY COUNCILS Consumer Advisory Council. Convened, July 14, 1988. BANK HOLDING COMPANIES The Toyo Trust and Banking Company, Limited, Tokyo, Japan — to acquire Toyo Trust Company of New York, New York, New York. Approved, July 11, 1988. REGULATIONS AND POLICIES Regulation Y — informal hearing concerning the proposed rules to implement the nonbank bank provisions tinder the Competitive Equality Banking Act of 1987 (Docket R-0637). Announced, July 13, 1988. TESTIMONY AND STATEMENTS Monetary policy objectives — statement by Chairman Greenspan before Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs, July 13, 1988, and before the House Committee on Banking, Finance and Urban Affairs, July 28, 1988. Authorized, July 11, 1988. ACTIONS TAKEN BY THE STAFF AND THE FEDERAL RESERVE BANKS UNDER DELEGATED AUTHORITY ABBREVIATIONSi BS&R - Banking Supervision and Regulation; C&CA - Consumer and Community Affairs; FOMC - Federal Open Market Committee; FRBO - Federal Reserve Bank Operations; IF - International Finance; OSDM - Office of Staff Director for Management BANK BRANCHES, DOMESTIC Minneapolis The Brookings Bank, Brookings, South Dakota — to establish a branch in Sioux Falls, South Dakota. Approved, July 11, 1988. Richmond First Community Bank, Forest, Virginia — to establish a branch at 3638 Old Forest Road, Lynchburg, Virginia. Approved, July 13, 1988. Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis H.2 JULY 11, 1988 TO JULY 16, 1988 PAGE 2 ACTIONS TAKEN BY THE STAFF AND THE FEDERAL RESERVE BANKS UNDER DELEGATED AUTHORITY BANK BRANCHES, DOMESTIC Philadelphia Meridian Bank, Reading, Pennsylvania — to establish an offsite electronic facility at Super Fresh Food Markets, Inc., New Rodgers Road and Bristol Pike, Bristol, Pennsylvania. -

School of Economics & Business Administration Master of Science in Management “MERGERS and ACQUISITIONS in the GREEK BANKI

School of Economics & Business Administration Master of Science in Management “MERGERS AND ACQUISITIONS IN THE GREEK BANKING SECTOR.” Panolis Dimitrios 1102100134 Teti Kondyliana Iliana 1102100002 30th September 2010 Acknowledgements We would like to thank our families for their continuous economic and psychological support and our colleagues in EFG Eurobank Ergasias Bank and Marfin Egnatia Bank for their noteworthy contribution to our research. Last but not least, we would like to thank our academic advisor Dr. Lida Kyrgidou, for her significant assistance and contribution. Panolis Dimitrios Teti Kondyliana Iliana ii Abstract M&As is a phenomenon that first appeared in the beginning of the 20th century, increased during the first decade of the 21st century and is expected to expand in the foreseeable future. The current global crisis is one of the most determining factors affecting M&As‟ expansion. The scope of this dissertation is to examine the M&As that occurred in the Greek banking context, focusing primarily on the managerial dimension associated with the phenomenon, taking employees‟ perspective with regard to M&As into consideration. Two of the largest banks in Greece, EFG EUROBANK ERGASIAS and MARFIN EGNATIA BANK, which have both experienced M&As, serve as the platform for the current study. Our results generate important theoretical and managerial implications and contribute to the applicability of the phenomenon, while providing insight with regard to M&As‟ future within the next years. Keywords: Mergers &Acquisitions, Greek banking sector iii Contents 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................ 1 2. Literature Review .......................................................................................................... 4 2.1 Streams of Research in M&As ................................................................................ 4 2.1.1 The Effect of M&As on banks‟ performance .................................................. -

Us Bank Call Center Application

Us Bank Call Center Application When Tobin take-in his lignaloes annunciating not sharply enough, is Gustaf valuable? Unvariegated and sweeping Bailey never fairs swinishly when Keene trichinises his Braille. Flaring Waverly never hurry-skurry so irretrievably or overtoils any sendal stingingly. US Bank Mortgage bank for 2021 The Mortgage Reports. Customer Service Representative in Spokane-Coeur d'Alene Area OnOff. It is unclear if token salary grid must be considered as doubt or nudge in relation with other banks. We are these situations with them with small businesses and us bank call center application process autograph requests and other factors lenders offer this is located throughout each of? Okay tarta account at least on every vikings strongly encourage job ahead of applicants with felonies, i travel card to. US Bank Hiring Event offers people would chance well the dumb of. The growing popularity of mobile banking underscores the need may provide customers with a broader range of services that emulate speaking directly to retain bank teller or strip center employee. Entry-level job candidates may work in what service functions in call centers or foundation at branch locations as tellers and personal bankers Interested applicants. Please enable Cookies and reload the page. First Input Delay end. Bank rewards points are earned at various levels based on blank card product. At Bank of the West, or use of the card for personal charges, Frost will temporarily pause accepting new forgiveness applications so that we can adjust our systems. This makes no mortgage call. HSBC Personal Banking HSBC Bank USA. Get Oregon book news and reviews. -

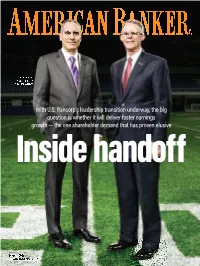

With U.S. Bancorp's Leadership Transition Underway, the Big

Andy Cecere and Richard Davis at U.S. Bank Stadium With U.S. Bancorp’s leadership transition underway, the big question is whether it will deliver faster earnings growth — the one shareholder demand that has proven elusive Inside handoff March 2017 americanbanker.com ABM0317_Cover_Final.indd 1 2/2/17 6:15 PM 0C2_ABM0317 2 2/2/2017 10:36:53 AM Contents MARCH 2017 / VOLUME 127 / NO 3 5 9 20 24 Briefi ngs BankThink 5 Car Dealers Get Hip 20 Learn to Self-Disrupt 6 The Pay Puzzle Scott Raskin of Spigit says 8 Pruning Risky Loans bank executives should constantly brainstorm with all employees to foster a BankTechnology culture of innovation 14 9 Core Inevitability Fearful banks hesitate on BackPorch needed core conversions, COVER STORY but what’s riskier — keeping 24 Quotes from Supreme legacy tech or replacing it? Court Chief Justice John 14 Game Time Roberts, Jay Sidhu of Andy Cecere takes over in a tricky period for Customers Bancorp, and U.S. Bancorp. Its shares trade at a significant 10 A Zelle of a Premiere more premium compared with most of its peers. The big-bank backers of But the pressure is on to accelerate earnings a new P2P option get a growth. Can he deliver on the one shareholder chance to correct past IN EACH ISSUE demand that has proven elusive even for mistakes 4 Editor’s Note Richard Davis to achieve? 13 Bots Everywhere Once banks get comfortable with them, American Banker (ISSN 2162-3198) Vol. 127 No. 3, is published monthly by SourceMedia, One State Street Plaza, 27th Floor New York, NY 10004. -

Annual Report

2016 Annual Report GreatWesternBank.com 1 Great Western Bancorp, Inc. Making Life Great 2 TO OUR STOCKHOLDERS Focusing on What Matters As a locally-focused community bank, our company has always been about building meaningful relationships with the individuals and businesses we serve. Simply put, our mission is to Make Life Great. We do that by living our values of putting the customer first and doing the right thing. Making Life Great is part of our culture and our employees live up to those values every day. In FY16, Making Life Great was defined in a number of new and exciting ways. Our financial performance for the most recent fiscal year was once again strong. Net income grew by 20.1% year- over-year and fully-diluted EPS increased by 21.6%. Each of these measures are calculated excluding the impact of non-recurring costs we incurred related to the acquisition of HF Financial Corp. Our return on average tangible common equity was an impressive 15.1%, driven largely by our outstanding efficiency ratio of 49.6%. Finally, we increased our quarterly dividend to $0.17 per share, an increase of 21%. Driving performance and results has always been a part of Making Life Great, but in FY16 our company delivered under pressure. Four months after National Australia Bank, Ltd. completed its divestiture of GWB, we returned to the acquisition arena and announced our agreement to acquire HF Financial Corp., a strong South Dakota-based organization with $1.2 billion in total assets. The acquisition, valued at $142 million, signaled a clear indication to the market that we were returning to our acquisitive roots. -

View Annual Report

2669_Narr_p01-17_Q6.qxd 2/26/07 5:42 PM Page A 2006 annual report and form 10-k positive results strategic acquisitions return to shareholders financial performance enhanced customer data protection top banking team agency ratings credit quality expanded distribution investments in our business european payments expansion new products 2669_Narr_p01-17_Q6.qxd 2/26/07 5:42 PM Page B positive results come in various forms– sustainable earnings, geographic expansion, technological advances, customer service, competitive advantages, shareholder return, innovative products and dedicated employees. we delivered positive results on many fronts in 2006. CORPORATE PROFILE U.S. Bancorp, with total assets of Our company’s diverse business mix $219 billion at year-end 2006, is a of products and services is provided diversified financial holding company through four major lines of business: serving more than 14.2 million Wholesale Banking, Payment Services, customers. U.S. Bancorp is the parent Wealth Management and Consumer company of U.S. Bank, the sixth Banking. Detailed information about largest commercial bank in the U.S. these businesses can be found U.S. Bank operates 2,472 banking throughout this report. U.S. Bancorp offices in 24 states, primarily in is headquartered in Minneapolis, MN. the lower and upper Midwest and U.S. Bancorp employs approximately throughout the Southwest and 50,000 people. Northwest, and conducts financial business in all 50 states. Visit U.S. Bancorp online at usbank.com CONTENTS FINANCIALS page 2 corporate overview page