Mountain Lion Scat

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Guide to Harmful and Toxic Creatures in the Goa of Jordan

Published by the Royal Marine Conservation Society of Jordan. P. O. Box 831051, Abdel Aziz El Thaalbi St., Shmesani 11183. Amman Copyright: © The Royal Marine Conservation Society of Jordan Reproduction of this publication for educational and other non- commercial purposes is authorized without prior written approval from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. ISBN: 978-9957-8740-1-8 Deposit Number at the National Library: 2619/6/2016 Citation: Eid, E and Al Tawaha, M. (2016). A Guide to Harmful and Toxic Creature in the Gulf of Aqaba of Jordan. The Royal Marine Conservation Society of Jordan. ISBN: 978-9957-8740-1-8. Pp 84. Material was reviewed by Dr Nidal Al Oran, International Research Center for Water, Environment and Energy\ Al Balqa’ Applied University,and Dr. Omar Attum from Indiana University Southeast at the United State of America. Cover page: Vlad61; Shutterstock Library All photographs used in this publication remain the property of the original copyright holder, and it should not be reproduced or used in other contexts without permission. 1 Content Index of Creatures Described in this Guide ......................................................... 5 Preface ................................................................................................................ 6 Part One: Introduction ......................................................................................... 8 1.1 The Gulf of Aqaba; Jordan ......................................................................... 8 1.2 Aqaba; -

Black Bear Attack Associations and Agency Risk Management

BLACK BEAR ATTACK ASSOCIATIONS AND AGENCY RISK MANAGEMENT By Janel Marie Scharhag A Thesis Submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree MASTER OF SCIENCE IN NATURAL RESOURCES (WILDLIFE) College of Natural Resources UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN-STEVENS POINT Stevens Point, Wisconsin May 2019 APPROVED BY THE GRADUATE COMMITTEE OF: _____________________________________________________________ Dr. Cady Sartini, Graduate Advisor, Assistant Professor of Wildlife _____________________________________________________________ Dr. Shawn Crimmins, Assistant Professor of Wildlife _____________________________________________________________ Dr. Scott Hygnstrom, Professor of Wildlife ____________________________________________________________ Dr. Jeff Stetz, Research Coordinator, Region IV Alaska Fish and Game ii ABSTRACT Attacks by bears on humans have increased in the United States as both human and bear populations have risen. To mitigate the risk of future attacks, it is prudent to understand past attacks. Information and analyses are available regarding fatal attacks by both black (Ursus americanus) and brown bears (U. arctos), and non-fatal attacks by brown bears. No similar analyses on non-fatal black bear attacks are available. Our study addressed this information gap by analyzing all agency-confirmed, non-fatal attacks by black bears in the 48 conterminous United States from 2000-2017. Government agencies across the country are responsible for species conservation, population management, and conflict control. State, federal, and tribal agencies are required to make decisions that communicate and mitigate the risk of an attack to the public. Agencies have been held legally responsible for those decisions, consuming time and money in litigation. This had led to a call for a more refined way to assess the risk of a bear attack with the creation of a risk management model (RMM). -

Human-Wildlife Conflict in the Chang Tang Region of Tibet

Human-Wildlife Conflict in the Chang Tang Region of Tibet: The Impact of Tibetan Brown Bears and Other Wildlife on Nomadic Herders Dawa Tsering, John Farrington, and Kelsang Norbu August 2006 WWF China – Tibet Program Author Contact Information: Dawa Tsering, Tibet Academy of Social Sciences and WWF China – Tibet Program Tashi Nota Hotel 24 North Linkuo Rd. Lhasa, Tibet Autonomous Region 850 000 People’s Republic of China [email protected] (+86)(891) 636-4380 John D. Farrington Tibet University 36 Jiangsu Road Lhasa, Tibet Autonomous Region 850 000 People’s Republic of China [email protected] [email protected] Kelsang Norbu WWF China – Tibet Program Tashi Nota Hotel 24 North Linkuo Rd. Lhasa, Tibet Autonomous Region 850 000 People’s Republic of China [email protected] Human-Wildlife Conflict in the Chang Tang Region of Tibet Abstract The multiple-use Chang Tang and Seling Lake Nature Reserves were created in 1993 to protect the unique assemblage of large fauna inhabiting the high-altitude steppe grasslands of northern Tibet, including the Tibetan antelope, Tibetan wild ass, Tibetan brown bear, Tibetan Gazelle, wild yak, and snow leopard. Prior to creation of the reserve, many of these species were heavily hunted for meat and sale of parts. Since creation of the reserve, however, killing of wildlife by subsistence hunters and commercial poachers has declined while in the past five years a new problem has emerged, that of human-wildlife conflict. With human, livestock, and wildlife populations in the reserves all increasing, and animals apparently emboldened by reserve-wide hunting bans, all forms of human-wildlife conflict have surged rapidly since 2001. -

1944 Wolf Attacks on Humans: an Update for 2002–2020

1944 Wolf attacks on humans: an update for 2002–2020 John D. C. Linnell, Ekaterina Kovtun & Ive Rouart NINA Publications NINA Report (NINA Rapport) This is NINA’s ordinary form of reporting completed research, monitoring or review work to clients. In addition, the series will include much of the institute’s other reporting, for example from seminars and conferences, results of internal research and review work and literature studies, etc. NINA NINA Special Report (NINA Temahefte) Special reports are produced as required and the series ranges widely: from systematic identification keys to information on important problem areas in society. Usually given a popular scientific form with weight on illustrations. NINA Factsheet (NINA Fakta) Factsheets have as their goal to make NINA’s research results quickly and easily accessible to the general public. Fact sheets give a short presentation of some of our most important research themes. Other publishing. In addition to reporting in NINA's own series, the institute’s employees publish a large proportion of their research results in international scientific journals and in popular academic books and journals. Wolf attacks on humans: an update for 2002– 2020 John D. C. Linnell Ekaterina Kovtun Ive Rouart Norwegian Institute for Nature Research NINA Report 1944 Linnell, J. D. C., Kovtun, E. & Rouart, I. 2021. Wolf attacks on hu- mans: an update for 2002–2020. NINA Report 1944 Norwegian In- stitute for Nature Research. Trondheim, January, 2021 ISSN: 1504-3312 ISBN: 978-82-426-4721-4 COPYRIGHT © Norwegian -

Sloth Bear Attacks on Humans in Central India: Implications for Species Conservation

Human–Wildlife Interactions 12(3):338–347, Winter 2018 • digitalcommons.usu.edu/hwi Sloth bear attacks on humans in central India: implications for species conservation Nisha Singh, Wildlife & Conservation Biology Research Lab, HNG University, Patan, Gujarat, India -384265 [email protected] Swapnil Sonone, Youth for Nature Conservation Organization, Amravati, Maharashtra, India - 444606 Nishith Dharaiya, Wildlife & Conservation Biology Research Lab, HNG University, Patan Gujarat, India -384265 Abstract: Conflicts with wild animals are increasing as human populations grow and related anthropogenic activities encroach into wildlife habitats. A good example of this situation is the increase in conflicts between humans and sloth bears (Melursus ursinus) in India. Sloth bears are known for their aggressive and unpredictable behavior. More human fatalities and injuries have been attributed to sloth bear attacks than all recorded incidences of wildlife attacks in Buldhana Forest Division of Maharashtra, India. We interviewed 51 victims that were attacked by sloth bears between 2009-2017 to better understand the reasons for the attacks. Thirty- four of the attacks (66.7%) resulted in serious injuries, and there were 7 human mortalities (13.7%) reported. Most attacks occurred close to agricultural fields (66.7%) and during mid- day (1100–1400 hours). More attacks (64.7%) occurred when a person was working or resting in the field, or retrieving water for the field followed by attacks while watching over grazing livestock (13.7%). Individuals aged 31 to 40 years (35.3%) were the most common victims of sloth bear attacks. Half of the attacks were during monsoon season (July to October, 51%) followed by summer (March to June, 35%) and winter (November to February, 14%). -

A Clinician's Guide to Australian Venomous Bites and Stings

Incorporating the updated CSL Antivenom Handbook Bites and Stings Australian Venomous Guide to A Clinician’s A Clinician’s Guide to DC-3234 Australian Venomous Bites and Stings Incorporating the updated CSL Antivenom Handbook Associate Professor Julian White Associate Professor Principal author Principal author Principal author Associate Professor Julian White The opinions expressed are not necessarily those of bioCSL Pty Ltd. Before administering or prescribing any prescription product mentioned in this publication please refer to the relevant Product Information. Product Information leafl ets for bioCSL’s antivenoms are available at www.biocsl.com.au/PI. This handbook is not for sale. Date of preparation: February 2013. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry. Author: White, Julian. Title: A clinician’s guide to Australian venomous bites and stings: incorporating the updated CSL antivenom handbook / Professor Julian White. ISBN: 9780646579986 (pbk.) Subjects: Bites and stings – Australia. Antivenins. Bites and stings – Treatment – Australia. Other Authors/ Contributors: CSL Limited (Australia). Dewey Number: 615.942 Medical writing and project management services for this handbook provided by Dr Nalini Swaminathan, Nalini Ink Pty Ltd; +61 416 560 258; [email protected]. Design by Spaghetti Arts; +61 410 357 140; [email protected]. © Copyright 2013 bioCSL Pty Ltd, ABN 26 160 735 035; 63 Poplar Road, Parkville, Victoria 3052 Australia. bioCSL is a trademark of CSL Limited. bioCSL understands that clinicians may need to reproduce forms and fl owcharts in this handbook for the clinical management of cases of envenoming and permits such reproduction for these purposes. However, except for the purpose of clinical management of cases of envenoming from bites/stings from Australian venomous fauna, no part of this publication may be reproduced by any process in any language without the prior written consent of bioCSL Pty Ltd. -

Industry Wide Labor-Management Safety

INDUSTRY WIDE LABOR-MANAGEMENT SAFETY COMMITTEE SAFETY BULLETIN #31 SAFETY AWARENESS WHEN WORKING AROUND INDIGENOUS WILDLIFE When working with animals and/or venomous reptiles refer to Safety Bulletins #6: “Animal Handling Rules for the Motion Picture Industry” and #12: “Guidelines for the Use of Venomous Reptiles.” This bulletin addresses special safety considerations when working on locations where various indigenous wildlife species may be present. Although the types of wildlife may vary from region to region, basic safeguards should be taken to prevent serious injury or illness to cast and crew members. Never touch or handle wildlife. Wild animals are not trained animal actors and are not familiar with humans. PRE-PLANNING "Wildlife" awareness starts during the initial search for locations. The location manager, his or her department representative, 1st AD, production management, studio safety department representative, and/or any medical personnel assigned to the project should consider safety precautions when pre-planning and preparing to use a location that may contain some type of indigenous wildlife. They should identify the type(s) of wildlife present, the location of nearby hospitals or medical facilities, and the availability of any anti-venom that may be required. Pre-planning may also include contacting the local zoo to see if they have the appropriate anti-venom and alerting them that you will be working in the area, especially if the production will be working with animal actors that could escape. Contact should be made with local wildlife authorities such as State Fish and Game to determine the protected status of indigenous wildlife in the area, and any special safety concerns. -

Subsistence Use of Brown Bear in Southeast Alaska

SUBSISTENCE USE OF BROWN BEAR IN SOUTHEAST ALASKA bY Thomas F. Thornton Technical Paper No. 214 Alaska Department of Fish and Game Division of Subsistence Juneau, Alaska February 1992 This research was partially supported by ANILCA Federal Aid finds administered through the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. EEO STATEMENT The Alaska Department of Fish and Game operates all of its public programs and activities free from discrimination on the basis of race, religion, color, national origin, age, sex, or handicap. Because the department receives federal funding, any person who believes he or she has been discriminated against should write to: O.E.0 U.S. Department of the Interior Washington, D. C. 20240 This report presents information on the historic and contemporary subsistence harvest and use of brown bear by southeast Alaskans. Although today brown bear are hunted primarily for sport and trophy, Alaskan Natives have harvested brown bear for food, clothing, tools, and other purposes for centuries. Traditionally, brown bear hunting among Natives was surrounded by numerous behavioral prescriptions which were considered vital to successin the hunt. Native stories, beliefs, and practices reflect these prescriptions and emphasize the close relationship between humans and brown bears. The brown bear remains a pervasive and important symbol in Tlingit social and ceremonial life. While sport and trophy harvests of brown bear have increased steadily since the turn of the century, ethnographic, harvest, and interview data suggest that the subsistence harvest of brown bears has declined from aboriginal levels. Possible factors contributing to the decline include: the low desirability of the meat in comparison with other game species; the availability of alternative and more economically viable resources; the labor-intensive methods of preservation; increased regulation of the harvest; and the erosion of the cultural complex of beliefs and practices surrounding bear hunting. -

Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife (Wdfw)

WASHINGTON DEPARTMENT OF FISH AND WILDLIFE (WDFW) ENFORCEMENT PROGRAM 2006 Annual Report wdfw.wa.gov/enf/enforce Table of Contents CHIEF’S INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................. 3 MISSION/VISION/VALUES ................................................................................................ 3 ENFORCEMENT PROGRAM 2006 DATA ......................................................................... 4 2006 Officer Hours...............................................................................................................................4 Enforcement Activity ............................................................................................................................5 Habitat Enforcement ............................................................................................................................5 Fish and Wildlife Enforcement by Species Category ...........................................................................6 HEADQUARTERS – OLYMPIA .......................................................................................... 7 Budget Information ..............................................................................................................................8 Recently-Enacted Legislation ..............................................................................................................8 Headquarters Data ..............................................................................................................................10 -

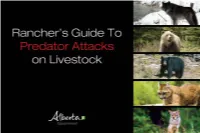

Rancher's Guide to Predator Attacks on Livestock READ MORE

Predation or Scavenging? Bears, wolves, cougars and coyotes can be scavengers as well as predators. Evidence of Scavenging Evidence of an Attack Scavenging • There may be no blood on the ground • There may be blood on the around the carcass, or blood may have ground indicating the animal drained onto the ground from body bled when attacked. Blood stains cavities such as the nose. may be spread widely around • Lacerations and puncture wounds the dead animal. There may be a found on the hide’s exterior do blood trail. not show corresponding signs of • Lacerations and puncture hemorrhaging on the interior of the wounds on the hide’s exterior hide or in adjacent tissue. will show corresponding signs • The body may be curled up with the of hemorrhaging on the interior legs tucked in, indicating the animal of the hide and tissue. Blood died of disease or other condition not may also drain from puncture related to predation. wounds. • The body may be stretched out in an unnatural position. 1 Examples of Scavenging Scavenging Though some feeding has occurred at the anus, there is no evidence of hemorrhaging or puncture wounds on the carcass or hide that would indicate 2 an attack had occurred. No hemorrhaging has occurred around the puncture wounds. Scavenging 3 Common Attack Zones on Adult Livestock Indications: hemorrhaging/bruising/lacerations/tears/bite marks/crushed bones Animal Attack Wolf Grizzly Black Cougar Coyote Bear Bear Tail X X Hindquarter/Groin X X Flank X X Behind and under front leg X X Withers X X Spine X X Neck X X X X Throat X X Skull X X X Spacing between canine teeth 1½-2” 2-3” 1½-2½” 1½-2¼” 1-1 3/8” Diameter of canine tooth punctures ¼” ¼” ¼” ¼” 1/8” 4 Characteristics of a wolf attack Wolves chase their prey. -

Investigation Team Report: Attacks by a Grizzly Bear in Soda Butte

Investigation Team Report – Bear Attacks in the Soda Butte Campground on July 28, 2010 1 INVESTIGATION TEAM REPORT Attacks by a grizzly bear in Soda Butte Campground on the Gallatin National Forest on July 28, 2010 August 13, 2010 Investigation Team Members1: Montana Fish Wildlife and Parks Department, Kevin Frey, Bear Management Specialist, Bozeman, MT Montana Fish Wildlife and Parks Department, Sam Shepard, Warden Captain, Bozeman, MT National Park Service, Kerry Gunther, Bear Management Supervisor, Yellowstone National Park, WY University of Calgary, Stephen Herrero, Environmental Science Program, Faculty of Environmental Designs, Calgary, AB, Canada. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Chris Servheen, Grizzly Bear Recovery Coordinator, Missoula, MT U.S. Forest Service, Dan Tyers, Yellowstone Grizzly Specialist, Bozeman, MT Wyoming Game and Fish Department, Mark Bruscino, Bear Management Supervisor, Cody, WY Summary: In the early morning hours of 28 July 2010, an adult female grizzly bear accompanied by 3 yearlings attacked 3 separate people in 3 different tents in the Soda Butte Campground. The initial attack was inflicted on Mr. Ronald Singer at approximately 0200 hours, who was bitten through his tent on his lower left leg. Mr. Singer punched the bear several times and the bear left. The second attack was inflicted on Mrs. Deborah Freele at approximately 0215 hours; she was initially bitten on her upper left arm and then bitten on her lower left arm. She then received a slight bite to her left leg and then the bear left. The third attack was inflicted on Mr. Kevin Kammer at an unknown time, presumably after the first 2 attacks. -

Bear Incidents Factsheet

bear incidents Typically purchased as cute, cuddly cubs, bears quickly mature into a lethal combination of long claws, sharp teeth, powerful jaws, and unpredictable behavior. Six adults have been killed, and more than 45 injured, by captive bears since 1990. At least a dozen children, including four 4-year-old boys have been injured. One child’s hand was nearly severed and three others lost fingers. The bears are victims, too. More than two dozen bears have been killed as a result of escapes or attacks. Following is a partial list of dangerous incidents involving captive bears, with some of the more notable items highlighted. “He was full of life, August 11, 2013/Beecher City, Illinois: A 64-year-old man was airlifted to a St. Louis hospital after he was mauled by his pet black bear at his rural USDA-licensed had a wonderful Fayette County farm. The man suffered a broken hip, broken leg, and bites to his 1 sense of humor, was arm after he entered the bear’s cage. The bear was killed. January 15, 2013/Collier County, Florida: A 125-pound grizzly bear cub escaped caring, and will be from an enclosure through an improperly locked door and then off the property of greatly missed by a traveling zoo called A Grizzly Experience. The bear was on the loose for three days before being tranquilized and recaptured by The Florida Fish and Wildlife everyone who loves Conservation Commission.2,3,4,5 him.” November 4, 2012/Bozeman, Montana: A 24-year-old man was mauled to death by one or both 500-pound male brown bears while cleaning their cage at Animals A mother’s note posted of Montana, a facility that trains wild animals for use in photo shoots and films.