Florida State University Libraries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

March 28, 2016 Via Email Sheriff Eric Watson Bradley

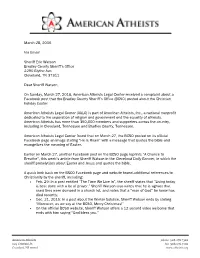

March 28, 2016 Via Email Sheriff Eric Watson Bradley County Sheriff’s Office 2290 Blythe Ave. Cleveland, TN 37311 Dear Sheriff Watson, On Sunday, March 27, 2016, American Atheists Legal Center received a complaint about a Facebook post that the Bradley County Sheriff’s Office (BCSO) posted about the Christian holiday Easter. American Atheists Legal Center (AALC) is part of American Atheists, Inc., a national nonprofit dedicated to the separation of religion and government and the equality of atheists. American Atheists has more than 350,000 members and supporters across the country, including in Cleveland, Tennessee and Bradley County, Tennessee. American Atheists Legal Center found that on March 27, the BCSO posted on its official Facebook page an image stating “He Is Risen” with a message that quotes the bible and evangelizes the meaning of Easter. Earlier on March 27, another Facebook post on the BCSO page reprints “A Chance to Breathe”, this week’s article from Sheriff Watson in the Cleveland Daily Banner, in which the sheriff proselytizes about Easter and Jesus and quotes the bible. A quick look back on the BSCO Facebook page and website found additional references to Christianity by the sheriff, including: Feb. 29: In a post entitled “The Time We Live In”, the sheriff states that “Living today is best done with a lot of prayer.” Sheriff Watson also writes that he is aghast that used tires were dumped in a church lot, and notes that a “man of God” he knew has died recently. Dec. 21, 2015: In a post about the Winter Solstice, Sheriff Watson ends by stating “Moreover, as we say at the BCSO, Merry Christmas!” On the official BCSO website, Sheriff Watson offers a 12-second video welcome that ends with him saying “God bless you.” American Atheists phone 908.276.7300 225 Cristiani St. -

Atheism” in America: What the United States Could Learn from Europe’S Protection of Atheists

Emory International Law Review Volume 27 Issue 1 2013 Redefining A" theism" in America: What the United States Could Learn From Europe's Protection of Atheists Alan Payne Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.emory.edu/eilr Recommended Citation Alan Payne, Redefining A" theism" in America: What the United States Could Learn From Europe's Protection of Atheists, 27 Emory Int'l L. Rev. 661 (2013). Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.emory.edu/eilr/vol27/iss1/14 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Emory Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Emory International Law Review by an authorized editor of Emory Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PAYNE GALLEYSPROOFS1 7/2/2013 1:01 PM REDEFINING “ATHEISM” IN AMERICA: WHAT THE UNITED STATES COULD LEARN FROM EUROPE’S PROTECTION OF ATHEISTS ABSTRACT There continues to be a pervasive and persistent stigma against atheists in the United States. The current legal protection of atheists is largely defined by the use of the Establishment Clause to strike down laws that reinforce this stigma or that attempt to deprive atheists of their rights. However, the growing atheist population, a religious pushback against secularism, and a neo- Federalist approach to the religion clauses in the Supreme Court could lead to the rights of atheists being restricted. This Comment suggests that the United States could look to the legal protections of atheists in Europe. Particularly, it notes the expansive protection of belief, thought, and conscience and some forms of establishment. -

The Impact of Religion on Values and Behavior in Kenya Naomi Wambui

THE IMPACT OF RELIGION ON VALUES AND BEHAVIOR IN KENYA NAOMI WAMBU50I European Journal of Philosophy, Culture and Religious Studies ISSN 2520-4696 (Online) Vol.1, Issue 1 No.1, pp50-65, 2017 www.ajpojournals.org THE IMPACT OF RELIGION ON VALUES AND BEHAVIOR IN KENYA 1* Naomi Wambui Post Graduate Student: Finstock University *Corresponding Author’s Email: [email protected] Abstract Purpose: The purpose of the study was to investigate the impact of religion on values and behaviour in Kenya. Methodology: The paper adopted a desk top research design. The design involves a literature review of existing studies relating to the research topic. Desk top research is usually considered as a low-cost technique compared to other research designs. Results: Based on the literature review, the study concluded that religion has positive impact on values and behavior. The study further concludes that a belief in fearful and punishing aspects of supernatural agents is associated with honest behavior, whereas a belief in the kind, loving aspects of gods is less relevant. Unique contribution to theory, practice and policy: The study recommended that policy makers should review policies involving religion by changing commonly held beliefs regarding the Constitution and religion. The study also recommended that religious leaders and parents take special care of the religious formation of children, especially during the transition period from childhood to adolescence, when they are most likely to lose their religious faith. Keywords: religion, values, behaviour 51 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background of the Study Religious practice appears to have enormous potential for addressing today's social problems. -

Religious Values in Indonesia's Character

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by eJournal of Sunan Gunung Djati State Islamic University (UIN) Ahmad Nadhif RELIGIOUS VALUES IN INDONESIA’S CHARACTER EDUCATION Ahmad Nadhif STAIN Ponorogo Jl. Pramuka No. 156 PO. BOX 116 Ponorogo 63471 Email: [email protected] ABSTRAK Penelitian ini bertujuan untuk menginvestigasi ideologi di balik peletakkan yang tercantum dalam Panduan Budaya dan Karakter Menteri Pendidikan yang diterbitkan pada tahun 2012. Penelitian ini dipaparkan sebagai bagian dari kurikulum pendidikan karakter dan memberi petunjuk pada guru tentang bagaimana melakukan implantasi untuk nilai-nilai moral yang baik dalam fikiran dan jiwa mereka. Isu pendidikan karakter menandai perubahan signifikan dalam kurikulum nasional pendidikan Indonesia yang menunjukkan potensi bagai pertarungan ideologi. Karenanya, hal ini merupakan isu penting untuk diteliti, khususnya dalam kajian Critical Discourse Analisis (CDA). Dengan menggunakan tiga model dimensional CDA Fairclough (1989), kurikulum Indonesia terkait dengan pendidikan berkarakter secara tekstual dianalisa. Analisa menunjukkan bahwa penggunaan nilai-nilai agama masih dipertanyakan; terkait dengan simbol dan jargon, agama sesungguhnya sangat dihargai; namun nampaknya hanyalah merupakan hal tak jelas untuk diam-diam menekan dan memarjinalkan core penting pengajaran. Kata Kunci: Pendidikan karakter, Nilai agama, CDA ABSTRACT This study aims at investigating the ideology behind the positioning of religion included in the Guidance of Culture and Character of the Nation of the Ministry of Education published in 2010. It is presented as part of the curriculum of character education and prescribes for teachers on how to conduct the implantation of good moral values in their students’ mind and heart. This issue of character education marks a significant shift in Indonesia’s national curriculum of education showing a potential to be a conflicting battleground of ideologies. -

Religion–State Relations

Religion–State Relations International IDEA Constitution-Building Primer 8 Religion–State Relations International IDEA Constitution-Building Primer 8 Dawood Ahmed © 2017 International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (International IDEA) Second edition First published in 2014 by International IDEA International IDEA publications are independent of specific national or political interests. Views expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent the views of International IDEA, its Board or its Council members. The electronic version of this publication is available under a Creative Commons Attribute-NonCommercial- ShareAlike 3.0 (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0) licence. You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the publication as well as to remix and adapt it, provided it is only for non-commercial purposes, that you appropriately attribute the publication, and that you distribute it under an identical licence. For more information on this licence visit the Creative Commons website: <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/> International IDEA Strömsborg SE–103 34 Stockholm Sweden Telephone: +46 8 698 37 00 Email: [email protected] Website: <http://www.idea.int> Cover design: International IDEA Cover illustration: © 123RF, <http://www.123rf.com> Produced using Booktype: <https://booktype.pro> ISBN: 978-91-7671-113-2 Contents 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................. 3 Advantages and risks ............................................................................................... -

1 Religion 205 Morality, Ethics, and Religion

RELIGION 205 MORALITY, ETHICS, AND RELIGION BULLETIN INFORMATION RELG 205 – Morality, Ethics, and Religion (3 credit hrs) Course Description: Values and ethics as developed, contested, and transmitted through a variety of religious practices. SAMPLE COURSE OVERVIEW This course offers a critical approach to discourse that associates religion with the development of values, ethics, and social responsibility. In the first part of the course, we take a broad look at some of the main issues related to an academic study of religion, with special attention to: the benefits and costs of equating religious practice with moral/ethical practice, the way that religion can function to authorize and legitimate certain ethical norms, and the implications or deviating from norms associated with divine or otherwise supernatural origins. In the second part of the course, we will examine specific kinds of religious practices (intellectual, ritual, emotional, and coercive) through which ideas about values and ethics are developed, prioritized, contested, adapted, and transmitted. Finally, in the third part of the course we will consider various ways to answer questions about the extent to which religion might or might not be necessary for moral and ethical development. ITEMIZED LEARNING OUTCOMES Upon successful completion of RELG 205, students will be able to: 1. Discuss the sources or origins of values and ethics as transmitted through various religious configurations; 2. Demonstrate an understanding of the different ways that religious practice shapes human attitudes toward values, ethics, and social responsibility; 3. Explain how religious values impact personal decision-making, self-identity, and individual well-being; 4. Analyze the influence of religious values upon community ethics and decision-making in contemporary society. -

The Role of Religious Values in Judicial Decision Making

Indiana Law Journal Volume 68 Issue 2 Article 3 Spring 1993 The Role of Religious Values in Judicial Decision Making Scott C. Idleman Indiana University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Courts Commons, and the Religion Law Commons Recommended Citation Idleman, Scott C. (1993) "The Role of Religious Values in Judicial Decision Making," Indiana Law Journal: Vol. 68 : Iss. 2 , Article 3. Available at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj/vol68/iss2/3 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Indiana Law Journal by an authorized editor of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Role of Religious Values in Judicial Decision Making SCOTT C. IDLEMAN* [U]nless people believe in the law, unless they attach a universal and ultimate meaning to it, unless they see it and judge it in terms of a transcendent truth, nothing will happen. The law will not work-it will be dead.' INTRODUCTION It is virtually axiomatic today that judges should not advert to religious values when deciding cases,2 unless those cases explicitly involve religion.' In part because of historical and constitutional concerns and in * J.DJM.P.A. Candidate, 1993, Indiana University School of Law at Bloomington; B.S., 1989, Cornell University. 1. HAROLD J. BERMAN, THE INTERACTION OF LAW AND RELIGION 74 (1974). 2. See, e.g., KENT GREENAWALT, RELIGIOUS CONVICTIONS AND POLITICAL CHOICE 239 (1988); Stephen L. -

What Is Atheism, Secularism, Humanism? Academy for Lifelong Learning Fall 2019 Course Leader: David Eller

What is Atheism, Secularism, Humanism? Academy for Lifelong Learning Fall 2019 Course leader: David Eller Course Syllabus Week One: 1. Talking about Theism and Atheism: Getting the Terms Right 2. Arguments for and Against God(s) Week Two: 1. A History of Irreligion and Freethought 2. Varieties of Atheism and Secularism: Non-Belief Across Cultures Week Three: 1. Religion, Non-religion, and Morality: On Being Good without God(s) 2. Explaining Religion Scientifically: Cognitive Evolutionary Theory Week Four: 1. Separation of Church and State in the United States 2. Atheist/Secularist/Humanist Organization and Community Today Suggested Reading List David Eller, Natural Atheism (American Atheist Press, 2004) David Eller, Atheism Advanced (American Atheist Press, 2007) Other noteworthy readings on atheism, secularism, and humanism: George M. Smith Atheism: The Case Against God Richard Dawkins The God Delusion Christopher Hitchens God is Not Great: How Religion Poisons Everything Daniel Dennett Breaking the Spell: Religion as a Natural Phenomenon Victor Stenger God: The Failed Hypothesis Sam Harris The End of Faith: Religion, Terror, and the Future of Religion Michael Martin Atheism: A Philosophical Justification Kerry Walters Atheism: A Guide for the Perplexed Michel Onfray In Defense of Atheism: The Case against Christianity, Judaism, and Islam John M. Robertson A Short History of Freethought Ancient and Modern William Lane Craig and Walter Sinnott-Armstrong God? A Debate between a Christian and an Atheist Phil Zuckerman and John R. Shook, eds. The Oxford Handbook of Secularism Janet R. Jakobsen and Ann Pellegrini, eds. Secularisms Callum G. Brown The Death of Christian Britain: Understanding Secularisation 1800-2000 Talal Asad Formations of the Secular: Christianity, Islam, Modernity Lori G. -

Triangle Atheists: Stigma, Identity, and Community Among

Triangle Atheists: Stigma, Identity, and Community Among Atheists in North Carolina’s Triangle Region by Marcus Larson Mann Graduate Program in Religion Duke University Date: __________________________ Approved: _______________________________ Leela Prasad, Co-Supervisor _______________________________ Mark Chaves, Co-Supervisor _______________________________ David Morgan Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Graduate Program in Religion of Duke University 2013 ABSTRACT Triangle Atheists: Stigma, Identity, and Community Among Atheists in North Carolina’s Triangle Region by Marcus Larson Mann Graduate Program in Religion Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Leela Prasad, Co-Supervisor ___________________________ Mark Chaves, Co-Supervisor ___________________________ David Morgan An abstract of a thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Graduate Program in Religion of Duke University 2013 Copyright by Marcus Larson Mann 2013 Abstract While there has been much speculation among sociologists on what the rise of religious disaffiliation means in the long-term for American religiosity, and if it can be considered a valid measure of broader secularization, the issue of if and how explicitly atheist communities are normalizing irreligion in the United States has received little attention. Adopting an inductive approach and drawing on one year of exploratory ethnographic research within one atheist community in North Carolina’s Triangle Region, including extensive participant-observation as well as nineteen in-depth interviews, I examine in what ways individuals within this community have experienced and interpreted stigma because of their atheistic views, how they have conceptualized and constructed their atheist identity, and how both of these things influence their motivations for seeking and affiliating with atheist organizations and communities. -

Exploring the Association Between Religious Values and Communication About Pain Coping Strategies: a Case Study with Vietnamese Female Cancer Patients

ISSN 1799-2591 Theory and Practice in Language Studies, Vol. 8, No. 9, pp. 1131-1138, September 2018 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17507/tpls.0809.04 Exploring the Association between Religious Values and Communication about Pain Coping Strategies: A Case Study with Vietnamese Female Cancer Patients Thuy Ho Hoang Nguyen University of Foreign Languages, Hue University, Vietnam Abstract—This study explores the association between the values of dominant religions in Vietnam and the communication about pain coping strategies employed by Vietnamese women who have cancer. Data was collected by means of in-depth interviews with twenty-six Vietnamese female cancer patients. Content analysis was then utilised to describe and interpret the women’s pain talks. Participants proposed six religion-related pain coping strategies, including accepting pain, bearing pain on one’s own, trying to change karma, being positive about pain, managing to forget pain and sharing pain when it becomes unbearable. The findings reflected that the religious values of Confucianism and Buddhism are associated with the patients’ communication about the strategies they employed to cope with their pain. Moreover, the language of communicating pain coping could be mapped onto the categories of passive language and active language, within the religion framework. The research has thus also confirmed the role of language in the communication about pain experience. Index Terms—pain coping strategies, religious values, Vietnamese culture, language of pain I. INTRODUCTION Amongst the cultural values that impact on pain communication, religion plays a particularly important role. Religion has been found to influence issues such as the quality of life, the communication about coping strategies and the mental health of those who undergo cancer treatment. -

Nonbelievers Nelson Tebbe Cornell Law School, [email protected]

Cornell University Law School Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository Cornell Law Faculty Publications Faculty Scholarship 9-2011 Nonbelievers Nelson Tebbe Cornell Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/facpub Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, and the Religion Law Commons Recommended Citation Tebbe, Nelson, "Nonbelievers," 97 Virginia Law Review 1111 (2011) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cornell Law Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NONBELIEVERS Nelson Tebbe* INTRODU CTION ................................................................................. 1112 I. N ONBELIEVERS ............................................................................. 1117 A. Who Are Nonbelievers? ....................................................... 1117 1. The Scope of the Study .................................................... 1117 2. D em ographics.................................................................. 1120 B. Are They Outsiders?............................................................. 1122 II. T H EO RY ........................................................................................ 1127 A . M ethod ................................................................................... 1127 B. -

Spirituality: History and Contemporary Developments – an Evaluation

Page 1 of 12 Original Research Spirituality: History and contemporary developments – An evaluation Author: Spirituality is increasingly becoming a popular concept both in the media and in academic 1 Anne C. Jacobs literature. However, there is a vast difference between the original concepts of spirituality, Affiliation: which were largely based on a Biblical view, and many contemporary perceptions thereof. 1School of Philosophy, Spirituality is generally seen as being divorced from any specific religion and specific truth North-West University, claims. Nevertheless, it can be stated that spirituality is now seen as a universal human Potchefstroom, South Africa phenomenon. An evaluation of these trends is attempted by studying the concept in its Correspondence to: original Biblical context, and by understanding the development of the dichotomy between Anne Jacobs religion and spirituality. Email: [email protected] Spiritualiteit: Geskiedenis en hedendaagse ontwikkelinge: ’n Evaluering. Spiritualiteit Postal address: word ’n toenemend populêre konsep, beide in die media en in akademiese literatuur. Dit is Internal Box 208, belangrik om op te merk dat daar ’n groot verskil is tussen die oorspronklike konsep van Potchefstroom Campus, spiritualiteit, wat op ’n Bybelse siening gegrond was, en baie van die hedendaagse persepsies North-West University, Private Bag X6001, daarvan. In die meeste gevalle word spiritualiteit tans beskou as iets wat van enige spesifieke Potchefstroom 2520, godsdiens asook spesifieke aansprake op waarheid geskei is. Daar kan wel gestel word dat South Africa spiritualiteit vandag as ’n universele menslike eienskap beskou kan word. Hierdie tendense word geëvalueer deur die konsep in die oorspronklike Bybelse konteks te bestudeer en deur Dates: Received: 03 Sept.