European School and the Group of Abstract Artists

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Luca Centenary Issue 1913 – 1994

!!! MAST HEAD ! Publisher: Contra Mundum Press Location: New York & Berlin Editor-in-Chief: Rainer J. Hanshe Guest Editor: Allan Graubard PDF Design: Giuseppe Bertolini Logo Design: Liliana Orbach Advertising & Donations: Giovanni Piacenza (To contact Mr. Piacenza: [email protected]) CMP Website: Bela Fenyvesi & Atrio LTD. Design: Alessandro Segalini Letters to the editors are welcome and should be e-mailed to: [email protected] Hyperion is published three times a year by Contra Mundum Press, Ltd. P.O. Box 1326, New York, NY 10276, U.S.A. W: http://contramundum.net For advertising inquiries, e-mail Giovanni Piacenza: [email protected] Contents © 2013 by Contra Mundum Press, Ltd. and each respective author. All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from Contra Mundum Press, Ltd. After two years, all rights revert to the respective authors. If any work originally published by Contra Mundum Press is republished in any format, acknowledgement must be noted as following and a direct link to our site must be included in legible font (no less than 10 pt.) at the bottom of the new publication: “Author/Editor, title, year of publication, volume, issue, page numbers, originally published by Hyperion. Reproduced with permission of Contra Mundum Press, Ltd.” Vol. VII, No. 3 (fall 2013) Ghérasim Luca Centenary Issue 1913 – 1994 Jon Graham, -

October Newsnet

October 2018 • v. 57, n. 5 NewsNet News of the Association for Slavic, East European, and Eurasian Studies Celebrating ASEEES: Reflections on the 1980s Ellen Mickiewicz, Duke University As we celebrate the 70th anniversary of our organization’s new and different system? What were we to make of the founding and the 50th Convention, we take time to reflect stops and starts, the halting changes of direction, and on our history through the eyes of four AAASS/ASEEES the obvious internal disagreements among the Soviet Past Presidents. Union’s political elite? Gorbachev’s program of reform, perestroika, sparked a good deal of disagreement in the AAASS brought into one professional organization West about what exactly it entailed, and if the Soviet scholars and policy makers working on issues related to leader had eventual democracy in mind or just limited the Soviet Union and beyond, including the then-Soviet- production improvements or a step-wise change that got dominated countries of Eastern, Central and South out of hand and roared ahead once controls were loosened. Europe. We were (and continue to be) affiliated and The Red Army withdrew from Afghanistan, and Soviet unaffiliated scholars, policy makers, media practitioners television for the first time characterized the conflict as and critics, and more. We included all relevant disciplines a “war” instead of a foreign aid mission to build schools. and added emerging ones. I became president in 1988, Television news had not showed the war and even was during turbulent years inside our organization and in the prohibited from letting the black smoke of bombs be world. -

Art Exhibitions Between 1920S and 1930S, Reflected in the Avant- Garde Magazine UNU

Învăţământ, Cercetare, Creaţie Vol. 7 No. 1 - 2021 171 Art Exhibitions between 1920s and 1930s, Reflected in the Avant- garde Magazine UNU Cristina GELAN1 Abstract: In the first decades of the twentieth century, when the trend of emancipation of Romanian culture - literature, but also art, under the influence of traditionalist direction and synchronization with European ideas became increasingly evident, the avant-garde movement proposed a series of aesthetic programs, aiming to impose a new vision, both in literature and in art. In this sense, the magazines founded during this period had a major role, even if many of them appeared for relatively short periods of time. Among them, there is the magazine UNU, a publication that appeared in Dorohoi, between April and December 1928, and later, between January 1929 and December 1932, in Bucharest. The magazine had declared itself surrealist and promoted the experiences of avant-garde events. Key-words: Romanian art; avant-garde; new art; UNU; surrealism 1. Introduction In the context of the first decades of the twentieth century, in which the trend of emancipation of Romanian culture - literature, but also art, under the influence of traditionalist direction and synchronization with European ideas became increasingly obvious, the avant- garde movement proposed a series of aesthetic programs, aiming to impose a new vision, both in literature and in art. In this sense, the magazines founded during this period had a major role, even if many of them appeared for relatively short periods of time. Among them, there is the magazine UNU, a publication that appeared in Dorohoi, between April and December 1928, and later, between January 1929 and December 1932, in Bucharest. -

Balint Juhasz Doctoral School of History, Pázmány Péter Catholic University

VI International Forum for Doctoral Candidates in East European Art History, Berlin, 3rd May 2019, organized by the Chair of East European Art History, Humboldt University Berlin Balint Juhasz Doctoral School of History, Pázmány Péter Catholic University The Italian trend of the Interwar Hungarian Neoclassicism Art in Transylvania Subject and main question of the PHD Project The Trianon Treaty of 4 June 1920 led to the break-up of certain regions from the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the birth of new nations. Before World War I, Hungarian artists from Transylvania were studying in Munich and Paris. Tightening the boundaries and breaking away from the motherland led to the creation of a new part of the country. In Transylvania, at the beginning of the 1920s, the only colony of artists at European level existed in Nagybánya (Baia Mare), where not only Hungarians but also Romanian and German students could learn. On the other hand, the artschool of Kolozsvár (Cluj) founded in 1925 and then relocated to Timisoara was an alternative solution. Aurel Ciupe, a Romanian artist who teached there, had a greater insight into European developments. Paris remained the most important station for Romanian artists in Bucharest and Transylvania. Nevertheless, some German artists like Max Hermann Maxy and Fritz Kimm preferred Berlin for retraining. By contrast, in the 1920s and 1930s, Italy underwent through a major transformation. Already in 1917 and 1918, many members of the Italian artistic generation, who survived the horrors of the war, forgot the lively optimism and radicalism of futurism. Leading figures as Giorgio de Chirico, Mario Sironi, and Felice Casorati have chosen the spirituality of Valori Plastici and Novecento. -

Gherasim Luca's Short Prose

Romanica Cracoviensia 3 (2020): 167–174 doi 10.4467/20843917RC.20.016.12938 www.ejournals.eu/Romanica-Cracoviensia Jakub Kornhauser http:/orcid.org/0000-0002-8904-9788 Jagiellonian University [email protected] GHERASIM LUCA’S SHORT PROSE: THE OBJECTS OF PREY (FIRST CHAPTER) ABSTRACT The paper continues “object-oriented” analysis of the most inspiring experiments in the Romanian Surrealism’s repertoire, notably in the short stories by Gherasim Luca, one of the movement’s leading representatives. His two books of poetic prose, published originally in the 1940s, could be interpreted as the emblematic example of Surrealist revolutionary tendencies in the field of new materialism. Such texts as The Kleptobject Sleeps or The Rubber Coffee become the laboratory of the object itself, gain- ing a new, unlimited identity in the platform of Surreality, where the human-like subject loses its status. Objects possess quasi-occult powers to initiate and control human’s desires. Therefore, Breton’s “revo- lution of the object” could concretize as literary praxis showing the way how contemporary “materialist turn” in anthropology deals with avant-garde theories. KEYWORDS: avant-garde, experimental prose, Surrealism, Gherasim Luca, Romanian literature. If we consider Passive Vampire (1945), which tends to be the highlight of Gherasim Luca’s Surrealist oeuvre, a textbook for learning the non-Oedipal world, his short stories written between 1940 and 1945 (18 texts of varied length collected in two books) would be a sort of an accompanying exercise book. While Vampire’s aim is to show the tota- lity of the author’s literary and philosophical endeavor, the oneiric stories are focused on a multitude of reading practices, sharing the spirit of negation of Luca’s subversive philosophical ideas. -

ROTES ANTIQUARIAT Katalog Frühjahr 2011 Kunst Und Literatur Titel-Nr

ROTES ANTIQUARIAT Katalog Frühjahr 2011 Kunst und Literatur Titel-Nr. 7 Inhaltsverzeichnis KUNST – Dokumentationen, illustrierte Bücher und graphische Folgen 3 Dadaismus, Futurismus und Surrealismus 6 Expressionismus 24 Fotografie 42 Konstruktivismus/ Funktionalismus 45 Sowjetische Propaganda 68 Der Sturm 70 Verismus 71 Einzelblätter 74 LITERATUR 90 EXIL 114 Wir sind jederzeit am Ankauf ganzer Sammlungen und einzelner Publikationen und Graphiken interessiert. Katalogbearbeitung: Friedrich Haufe Kataloggestaltung: Markéta Cramer von Laue Fotografie: Lara Siggel Übersetzungen: Constanze Hager u.a. Orders from the USA: [email protected] Bestellungen bitte an: Rotes Antiquariat und Galerie C. Bartsch Knesebeckstr. 13/14, 10623 Berlin-Charlottenburg Tel. 030-37 59 12 51, Fax 030-31 99 85 51 [email protected] Mitglied im Bankverbindung: Member of Christian Bartsch Postbank Berlin, Konto-Nr. 777 844 102 Deutsche Bank, Konto-Nr. 135 687 200 Für unsere Schweizer Kunden Christian Bartsch, Konto 91-392193-5, PostFinance Schweiz Steuer-Nummer 34/217/58303 USt-ID 196559745 Katalog Frühjahr 2011 Kunst und Literatur Seite 5 Kunst I KUNST DOKUMENTATIONEN,ILLUSTRIERTE BÜCHER UND GRAPHISCHE FOLGEN 1. Abstraction, Création, Art non figurativ. 1932. Heft 1 (von 5). (Paris). 1932. 48 S. Mit zahlr. Abb. 4°, Orig.-Umschlag. (Bestell-Nr. KNE10061) 800,- € Original-Ausgabe. - "Abstraction-Création" vereinte die beiden Gruppen "Cercle et Carré" und die aus ihr hervorgegangene, vor allem durch van Doesburg initiierte Abspaltung "Art concret"; die Zusammenfügung -

Lista Proiectelor Organizate De Reprezentanțele ICR Din Străinătate În Luna Aprilie 2017

Lista proiectelor organizate de reprezentanțele ICR din străinătate în luna aprilie 2017 Institutul Cultural Român de la Beijing 12, 18 aprilie / Conferința „Cultura României descoperită de studenții chinezi“ a avut loc în data de 12 aprilie, la Academia de Arte din Beijing și apoi în data de 18 aprilie, la Universitatea de Studii Străine din Beijing, la solicitarea celor două instituții de învățământ. Conferințele au fost susținute de directorul ICR Beijing, Constantin Lupeanu, în limba chineză. Prima prelegere a avut ca temă „România – dezvoltarea artelor plastice în România și grafica românească“, iar cea de-a doua „România – limbă, cultură și civilizație“, fiecare temă fiind aleasă în funcție de profilul instituției unde a avut loc. Proiectul a fost organizat în colaborare cu Academia de Arte din Beijing și cu Universitatea de Studii Străine din Beijing. 16 aprilie – 3 mai / Participarea artistului Vlad Basarab la la Bienala Internațională de Ceramică de la Gyeonggi, Coreea de Sud la 4th Hong Guang Zi Qi International Ceramic Art Festival“, la Kai Hong Tang Art Museum din Yixing, provincia Jiangsu, China (desfășurată în perioada 15 – 28 aprilie 2017) și la evenimentele conexe organizate în cadrul celor două expoziții. Vlad Basarab a prezentat portul tradițional românesc în cadrul ceremoniei de deschidere a expoziției internaționale de ceramică, a susținut o prelegere în fața studenților de la Institutul de Tehnologie din Wuxi, China (Wuxi Institute of Technology), în data de 27 aprilie, a realizat artist talk-uri în cadrul Centrului Mondial de Ceramică din Icheon, Coreea de Sud (Icheon World Ceramic Center), în perioada 29-30 aprilie. În cadrul Bienalei Internaționale de Ceramică de la Gyeonggi, Coreea de Sud, artistul Vlad Basarab a participat cu filmul Arheologia Memoriei – Instalație. -

Caiete Diplomatice Anul II, 2014, Nr

Institutul Diplomatic Rom ân Caiete Diplomatice Anul II, 2014, nr. 2 DIN SUMAR: ♦ Relaţiile bilaterale România-Israel (1948-1959) ♦ Jurnalul de călătorie al arhiducelui Rudolf de Habsburg în Transilvania ♦ Situaţia emigraţiei române din S.U.A. şi Canada ♦ Recenzii şi note de lectură www.idr.ro ISSN 2392 – 618X ISSN-L 2392 – 618X INSTITUTUL DIPLOMATIC ROMÂN CAIETE DIPLOMATICE Anul II, 2014, Nr. 2 COMITETUL DE REDAC ŢIE : Mioara ANTON, Bogdan ANTONIU, Ovidiu BOZGAN (redactor şef), Lauren ţiu CONSTANTINIU, Alin CIUPAL Ă, Antal LUKÁCS (redactor şef adjunct), Andrei ŞIPERCO, Delia VOICU (responsabil de num ăr). A mai colaborat la apari ţia acestui num ăr: Constantin CONSTANTINESCU. © Institutul Diplomatic Român Reproducerea integral ă sau par ţial ă a textelor publicate în revista „Caiete Diplomatice”, fără acordul Institutului Diplomatic Român, este interzis ă. Responsabilitatea asupra con ţinutului textelor publicate şi respectarea principiilor eticii profesionale revin în exclusivitate autorilor. 3 SUMAR STUDII Florin C. STAN , Rela ţiile bilaterale România-Israel (1948-1959). O cronologie....................................................................................................................... 5 Iulian TOADER , Participarea României la consult ările preliminare pentru C.S.C.E. şi M.B.F.R. (noiembrie 1972-iunie 1973).......................................................... 44 SURSE DE ISTORIE DIPLOMATIC Ă Antal LUKACS , Jurnalul de c ălătorie al arhiducelui Rudolf de Habsburg în Transilvania (comitatul Hunedoara) din anul 1882........................................................ -

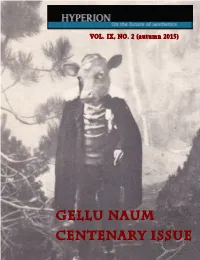

Gellu Naum Centenary Issue

VOL. IX, NO. 2 (autumn 2015) GELLU NAUM CENTENARY ISSUE !!! MAST HEAD Publisher: Contra Mundum Press Location: New York, London, Paris Editors: Rainer J. Hanshe, Erika Mihálycsa PDF Design: Giuseppe Bertolini Logo Design: Liliana Orbach Advertising & Donations: Giovanni Piacenza (To contact Mr. Piacenza: [email protected]) Letters to the editors are welcome and should be e-mailed to: [email protected] Hyperion is published biannually by Contra Mundum Press, Ltd. P.O. Box 1326, New York, NY 10276, U.S.A. W: http://contramundum.net For advertising inquiries, e-mail Giovanni Piacenza: [email protected] Contents © 2015 Contra Mundum Press & each respective author unless otherwise noted. All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from Contra Mundum Press. Republication is not permitted within six months of original publication. After two years, all rights revert to each respective author. If any work originally published by Contra Mundum Press is republished in any format, acknowledgement must be noted as following and include, in legible font (no less than 10 pt.), a direct link to our site: “Author, work title, Hyperion: On the Future of Aesthetics, Vol. #, No. # (YEAR) page #s. Originally published by Hyperion. Reproduced with permission of Contra Mundum Press.” Vol. IX, No. 2 — GELLU NAUM CENTENARY ISSUE Curated by Guest Editor VALERY OISTEANU 0 Valery Oisteanu, Gellu Naum: Surreal-Shaman of Romania 16 Petre Răileanu, Poésie & alchimie 25 Petre Răileanu, Poetry & Alchemy 36 Sebastian Reichmann, Ici & Maintenant (de l’Autre Côté).. -

Minirevista Comunitatii Evreiesti Din Focsani Minirevista Comunitatii Evreiesti Din Focsani

NR.7 Iulie APARITIE 2017 LUNARA MINIREVISTA COMUNITATII EVREIESTI DIN FOCSANI MINIREVISTA COMUNITATII EVREIESTI DIN FOCSANI MINIREVISTA COMUNITATII EVREIESTI DIN FOCSANI RA MINIREVISTA COMUNITATII EVREILOR FOCSANI 1.Stiri din Israel …. … pag.3 2.Stiri din Vrancea …. … pag.4 COLECTIVUL REDACTIONAL: 3.Stiri din lume .… … pag.5 4.Info Juridic …. … . pag.6-7 5.Pagina de istorie …... … .pag.8 – Mircea Rond – 6. Din secretele istoriei …… …... pag.9 Presedintele C.Ev. 7. Calendarul lunii Iulie ….……....pag.10 8. Planeta UMOR … ………… pag.11 Focsani (Vrancea),Buzau SANATATE Harieta Rond – 9. Sfatul medicului …… …. …... .. pag.12-13 - Secretara – 10. Plante Medicinale ……… .. pag.14-15 11. Cele mai bune sfaturi … … .…… pag.16 12. Muzee din Romania …....pag.17-18 13. Mozaic Stiintific …….. ………..…pag. 19 14. Stiati ca …... … ……. …....pag.20-21 15. Stiri mondene …… .pag.22 ADRESA REDACTIEI: 16. Info Club . ……....--.pag.23 STR. OITUZ NR. 4, FOCSANI, VRANCEA. SCRISORI LA REDACTIE TEL: 0237/623959 MOBIL: 0745171287 17. Sub Steaua lui David,cu E-MAIL: Dumnezeu………………….pag.24-25 18. Savanti romani …………………... pag.26-27 [email protected] 19. La pas prin tara …… ………….. ….. pag.28 20. Evreii în istoria oraşului Siret …. pag.29-30 31. Comunitatea Evreilor din Râmnicu Sărat la SITE: www.focsani.jewish.ro sfârșitul sec. al XIX-lea ……………...pag.31 E-Mail : [email protected] MINIREVISTA COMUNITATII EVREILOR FOCSANI ** -India şi Israelul plănuiesc să coopereze în mai multe domenii, de la tehnologia spaţială şi gestionarea resurselor de apă şi până la combaterea terorismului, au anunţat miercuri premierii celor două ţări, în urma unei întâlniri desfăşurate la Ierusalim . Premierul israelian Benjamin Netanyahu a afirmat că a discutat cu omologul său indian Narendra Modi, care se află într-o vizită de trei zile în Israel - prima efectuată de un şef al guvernului indian în statul evreu - despre posibilităţile de cooperare în domenii pe care amândoi le consideră importante pentru ambele ţări. -

Ars Libri Ltd Modernart

MODERNART ARS LIBRI LT D 149 C ATALOGUE 159 MODERN ART ars libri ltd ARS LIBRI LTD 500 Harrison Avenue Boston, Massachusetts 02118 U.S.A. tel: 617.357.5212 fax: 617.338.5763 email: [email protected] http://www.arslibri.com All items are in good antiquarian condition, unless otherwise described. All prices are net. Massachusetts residents should add 6.25% sales tax. Reserved items will be held for two weeks pending receipt of payment or formal orders. Orders from individuals unknown to us must be accompanied by pay- ment or by satisfactory references. All items may be returned, if returned within two weeks in the same con- dition as sent, and if packed, shipped and insured as received. When ordering from this catalogue please refer to Catalogue Number One Hundred and Fifty-Nine and indicate the item number(s). Overseas clients must remit in U.S. dollar funds, payable on a U.S. bank, or transfer the amount due directly to the account of Ars Libri Ltd., Cambridge Trust Company, 1336 Massachusetts Avenue, Cambridge, MA 02238, Account No. 39-665-6-01. Mastercard, Visa and American Express accepted. June 2011 avant-garde 5 1 AL PUBLICO DE LA AMERICA LATINA, y del mondo entero, principalmente a los escritores, artistas y hombres de ciencia, hacemos la siguiente declaración.... Broadside poster, printed in black on lightweight pale peach-pink translucent stock (verso blank). 447 x 322 mm. (17 5/8 x 12 3/4 inches). Manifesto, dated México, sábado 18 de junio de 1938, subscribed by 36 signers, including Manuel Alvárez Bravo, Luis Barragán, Carlos Chávez, Anto- nio Hidalgo, Frieda [sic] Kahlo, Carlos Mérida, César Moro, Carlos Pellicer, Diego Rivera, Rufino Tamayo, Frances Toor, and Javier Villarrutia. -

147683442.Pdf

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Archivio della Ricerca - Università di Pisa ANALELE UNIVERSITĂŢII BUCUREŞTI LIMBA ŞI LITERATURA ROMÂN Ă 2 0 1 7 SUMAR • SOMMAIRE • CONTENTS MIRCEA ANGHELESCU, Al. Cior ănescu: La Renaissance ou la revanche des morts ..... 3 IULIANA CHIRICU, Figurile de stil în conversa ţie ........................................................... 19 EMILIA DAVID, Le collaborazioni di Max Hermann Maxy e di Hans Mattis-Teutsch con Der Sturm, Ma e Integral . Affinita costruttiviste nelle avanguardie storiche .......... 41 ANNAFRANCESCA NACCARATO, « La parole de l’eau » dans la poésie de Benjamin Fondane ... 59 CATRINEL POPA, Seduc ţia lumilor (im)posibile. Note despre proza lui Urmuz .............. 77 DANILO DE SALAZAR, Sviluppi nello studio della sinestesia letteraria in ambito linguistico italiano e romeno ................................................................................... 87 VALENTINA SIRANGELO, Lucian Blaga e Arturo Onofri: una poesia della notte cosmica ... 107 ALAIN VUILLEMIN, Le renoncement à la liberté dans Monsieur K. libéré (Domnul K. eliberat – 2010) de Matei Vi şniec ........................................................................... 123 Recenzii / Comptes rendus / Reviews Michel Pastoureau, Rouge. Histoire d'une couleur , Paris, Éditions du Seuil, 2016, 216 p. (Laura Dumitrescu) ................................................................................................. 137 Geoff Thompson, Laura Alba-Juez (eds.), Evaluation in Context , Amsterdam/Philadelphia, John Benjamins Publishing Company, 2014, 418 p. (Alina Partenie) ..................... 139 Gabriela Stoica, Afect şi afectivitate. Conceptualizare şi lexicalizare în româna veche, Bucure şti, Editura Universit ăţ ii din Bucure şti, 2012, 435 p. (Liliana Hoin ărescu) ..... 142 2 Adina Huluba ș, Ioana Repciuc (eds.), Riturile de trecere în actualitate / The Rites of Passage Time after Time , Ia şi, Editura Universit ății „Alexandru Ioan Cuza”, 2016, 395 p.