Air University Review March-April 1972

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cy Martin Collection

University of Oklahoma Libraries Western History Collections Cy Martin Collection Martin, Cy (1919–1980). Papers, 1966–1975. 2.33 feet. Author. Manuscripts (1968) of “Your Horoscope,” children’s stories, and books (1973–1975), all written by Martin; magazines (1966–1975), some containing stories by Martin; and biographical information on Cy Martin, who wrote under the pen name of William Stillman Keezer. _________________ Box 1 Real West: May 1966, January 1967, January 1968, April 1968, May 1968, June 1968, May 1969, June 1969, November 1969, May 1972, September 1972, December 1972, February 1973, March 1973, April 1973, June 1973. Real West (annual): 1970, 1972. Frontier West: February 1970, April 1970, June1970. True Frontier: December 1971. Outlaws of the Old West: October 1972. Mental Health and Human Behavior (3rd ed.) by William S. Keezer. The History of Astrology by Zolar. Box 2 Folder: 1. Workbook and experiments in physiological psychology. 2. Workbook for physiological psychology. 3. Cagliostro history. 4. Biographical notes on W.S. Keezer (pen name Cy Martin). 5. Miscellaneous stories (one by Venerable Ancestor Zerkee, others by Grandpa Doc). Real West: December 1969, February 1970, March 1970, May 1970, September 1970, October 1970, November 1970, December 1970, January 1971, May 1971, August 1971, December 1971, January 1972, February 1972. True Frontier: May 1969, September 1970, July 1971. Frontier Times: January 1969. Great West: December 1972. Real Frontier: April 1971. Box 3 Ford Times: February 1968. Popular Medicine: February 1968, December 1968, January 1971. Western Digest: November 1969 (2 copies). Golden West: March 1965, January 1965, May 1965 July 1965, September 1965, January 1966, March 1966, May 1966, September 1970, September 1970 (partial), July 1972, August 1972, November 1972, December 1972, December 1973. -

August 14, 1972 Issue (Dig081472.Pdf)

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION A Daily Summary of ~~~~ @il@~~~ S.E.C. Activities (Prepared by the SEC Office of Public Information) (Issue No. 72-154) FOR R E L EA S E _A~ug,,-u,--s_t.----,-14_,~1~9~72~_ COMMISSION ANNOUNCEMENT TRADING SUSPENSION IN COGAR CORPORATION LIFTED. The SEC on August 11 ordered the term1natlon of the sus- penslon of tradlng In the securlt,es of Cogar Corporatlon, effect1ve at the open of buslness on Tuesday August 15, 1972. The Commlssl0n f,rst ordered the suspensl0n of tradlng on Aprll 17, 1972. Th,S suspenslon, WhlCh was requested by Cogar, was ordered 1n order to permlt d,ssem,nat,on by Cogar of lnformatlon concernlng recent adverse corporate developments. On Aprl1 17, 1972, Cogar announced that ItS cash supply had been exhausted and further that the company was attemptlng to pursue varlous alternat,ves that m1ght allow the company to contlnue lts buslness. Cogar has Issued a release today WhlCh summarlzes the current status of the company's buslness and f,nanclal condltlon. Therefore, the Commlsslon has author,zed the 11ftlng of ItS suspensl0n. (ReI. 34-9728) COURT ENFORCEME~~ ACTIONS COMPLAINT NAMES NORTHWEST PACIFIC ENTERPRISES, INC., SIX OTHERS. The SEC Seattle Reg10nal Office announced the fl1lng on August 3 of a complalnt 1n the Federal Court In Seattle, Washlngton seeklng to enjoln Northwest Pac,f,c Enterpr1ses, Inc., a Utah corporatlon, J. Cameron Cutler of Seattle, Francls C. Lund of Salt Lake Clty, Utah, Robert M. Bryson of Salt Lake Clty, and RIchard ~~tuszewskl of Seattle, from further v,olat,ng the antl- fraud and reglstrat10n provislons of the Federal securitles laws In connectlon WIth the offer and sale of the common stock of Northwest Paclf,c Enterprises, Inc. -

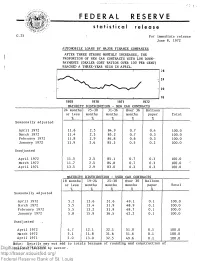

Federal Reserve

FEDERAL RESERVE statistical release For immediate release June 8, 1972 AUTOMOBILE LOANS BY MAJOR FINANCE COMPANIES AFTER THREE STRONG MONTHLY INCREASES, THE PROPORTION OF NEW CAR CONTRACTS WITH LOW DOWN- PAYMENTS (DEALER COST RATIOS OVER 100 PER CENT) REACHED A THREE-YEAR HIGH IN APRIL. 1969 1970 1971 1972 MATURITY DISTRIBUTION - NEW CAR CONTRACTS 24 months 25-30 31-36 Over 36 Balloon months months months P Total % 70 % 7o % Seasonally adjusted April 1972 11.6 2.5 84.9 0.7 0.4 100.0 March 1972 11.4 2.5 85.2 0.7 0.3 100.0 February 1972 11.8 2.9 84.8 0.6 0.3 . 100.0 January 1972 11.9 2.6 85 .3 0.5 0.2 100.0 Unadjusted April 1972 11.5 2.5 85.1 0.7 0.3 100.0 March 1972 11.7 2.5 84.8 0.7 0.3 100.0 April 1971 13.5 2.9 83.0 . 0.3 0.3 100.0 MATURITY DISTRIBUTION - USED CAR CONTRACTS 18 months 19-24 25-30 Over 30 Balloon months months months P Total % 7= % % % Seasonally adjusted April 1972 5.2 13.6 31.6 49.1 0.1 100.0 March 1972 5.5 13.4 31.9 48.9 0.1 100.0 February 1972 5.5 13.2 31.9 48.7 0.1 100.0 January 1972 5.8 • 15.9 36.5 42.2 0.1 100.0 Unadjusted April 1972 4.7 12.1 32.1 51.0 0.1 100.0 March 1972 5.1 11.8 31.6 51.6 0.1 100.0 April 1971 5 .0 13.0 32.5 49.6 0.1 100.0 Note: Details may not add to totals because of rounding and construction of Digitizedseasona for FRASERl factors by sector. -

Protocol Relating to an Amendment to the Convention on International Civil Aviation

PROTOCOL RELATING TO AN AMENDMENT TO THE CONVENTION ON INTERNATIONAL CIVIL AVIATION ARTICLE 56, SIGNED AT VIENNA ON 7 JULY 1971 Entry into force: The Protocol entered into force on 19 December 1974. Status: 136 parties. State Date of deposit of instrument of ratification Algeria 2 February 1977 Andorra (5) 25 February 2001 Angola 10 April 1977 Antigua and Barbuda 17 October 1988 Argentina 18 August 1972 Australia 4 March 1974 Austria 10 September 1973 Bahrain 1 November 1971 Barbados 6 January 1972 Belarus 24 July 1996 Belgium 16 February 1972 Benin 30 March 2004 Bolivia (Plurinational State of) 30 December 1974 Bosnia and Herzegovina 7 March 1995 Botswana 28 March 2001 Brazil 17 December 1971 Brunei Darussalam 25 August 2000 Bulgaria 12 April 1972 Burkina Faso 15 June 1992 Cameroon 8 August 1972 Canada 3 December 1971 Chad 2 March 1973 Chile 6 September 1972 China (1) 28 February 1974 Congo 13 November 1978 Cook Islands 29 August 2005 Croatia 5 October 1993 Cuba 3 January 1975 Cyprus 5 July 1989 Czech Republic 15 April 1993 Democratic People’s Republic of Korea 27 June 1978 Democratic Republic of the Congo 22 January 1973 Denmark 10 September 1971 Dominica (12) 14 March 2019 Dominican Republic 30 May 1972 Ecuador 2 May 1975 Egypt 17 July 1972 El Salvador 13 February 1980 Eritrea 6 June 1995 Estonia 21 August 1992 Eswatini 31 January 1974 Ethiopia 9 September 1971 Finland 7 October 1971 France 13 September 1972 Gabon 10 January 1973 Gambia 25 January 1978 Germany (2) 16 September 1977 Greece 15 November 1971 Guatemala 11 February 1974 -

Analysis of Wilmington Ohio Housing Market As of April 1

728.I :308 F22 Wtlmington N. C. L9Tz Analysis of the .-, i." i I i, lj. rr 6., ii ''u,,: f , '. - '';i,, WLMINGTON, NORTH CAROLINA HOUSING MARKET as of April 1,1972 A Beport by the OEPARTMENT t)F HOUSING ANO URBAN DEVELOPMENT FEDERAL HOUSING ADMINISTRATION wAsHrNGT0N, D.C. 20411 November 1972 Housing Market Analysis Wilmington, North Carolina, as of April I 1972 Foreword This analysis has been prepared for the assistance and guidance of the Department of Housing and Urban \ Development in its operations. The factual infor- mation, findings, and conclusions may be useful also I to builders, mortgagees, and others concerned with local housing problems and trends. The analysis does no! purport to make determinations with respect to the acceptability of any particular mortgage in- surance proposals that may be under consideration in the subject locality. The factual framework for this analysis was devel- oped by the Economic and Market Analysis Divislon as thoroughly as possible on the basis of informa- tion available on the "as of" date from both 1oca1 and national sources. Of course, estimates and judgments made on the basis of information avail- able on the "as of" date may be modified consider- ably by subsequent market developments. The prospective demand or occupancy potentials ex- pressed in the analysis are based upon an evalua- tion of the factors available on the "as of" date. They cannot be construed as forecasts of building activity; rather, they express the prospective housing production which would maintain a reason- able balance in deuand-supply relationships under conditions analyzed for the "as of" date. -

Name Files 807 Abshire, David M

Name Files 807 Abshire, David M. [June 28, 1973] Acheson, Dean [1969-1971] Acheson meeting with President March 19, 1969 [Empty] Agnew, Harold M. Dr. [May-July 1971] Box Folder Date Extent Aiken - Cooper Mtg. (Senators) [1970-1971] Alexander, Lamar [1969-1970] Allen, R.V. [1969-1971] Allin, Mort [May 7, 1970] Alsop, Joseph [1969-1973] Anderson, Jack [1971-1972] Anderson, Martin [September 9, 1969] Anderson, Robert [1969-1973] Armstrong, Willis [December 1969-July 1970] Aubrac, Raymond [1971-1972] 808 Baker, Richard T. [April 1971] Barnett, Richard [December 1969] Bauer, Etienne [August 1971] Behr, Robert M. Col. [May 1971-April 1972] Archbishop Benelli [January 1970] Bergford, James [February 1970] Berry, Sidney B. Brig Gen. [October 1970] Box Folder Date Extent Name Files 808 Black, Eugene [April 1969-March 1970] Black, Shirley Temple [February 1970-June 1974] Blocker, Joel [October-December 1969] Bohlen, Charles E. [June 1969-August 1971] Borman, Frank [January-October 1969] Bowles, Chester [March-April 1970] Brandon, Henry [September 1969-July 1971] Brooke, Edward W. [July 1971-April 1973] Brown, Harold [May 1970-May 1971] Brown, John R. III [February 1969-February 1971] 809 Brownell, Herbert [August 1969-August 1972] Bruce, David [April 1969-July 1971] Buchanan, Patrick J. [March 1969-August 1973] Buckley, William [May 1970-August 1972] Bull, Steve [December 1971-April 1973] Bundy, McGeorge (The Ford Foundation) [September 1969-October 1971] Bunker, Ellsworth [June 1973] Box Folder Date Extent Name Files 809 (Gen.) Burchinal [December 1969-June 1971] Burchett, Wilfred [June 1969-November 1971] 810 Burke, Arleigh (Adm. Ret) [1973] Burns, Arthur F. [1969-1973] Bushnell, John [October 1973] Butterfield, Alexander P. -

Commandant's Annual Report, 1971-1972

ANNUAL REPORT 1971-1972 The Judge Advocate General's School U. S. Army Charlottesville, Virginia 22901 . , SHOULDER SLEEVE INSIGNIA APPROVED FOR JAG SCHOOL Under the provisions of paragraphs 14-16, AR 670-5, the Com mandant received approval on 21 January 1972 for a shoulder sleeve insignia for uniform wear by Staff, Faculty, and Advanced Class personnel of The Judge Advocate General's School from the Chief of Heraldry, Institute of Heraldry, U.S. Army. The patch design is adapted from the School's distinctive crest. It is em blazoned across a shield of traditional blue. Its lighted torch symbolizes the illumination of intellect and leadership supplied by the School. The torch is surmounted by a gold open laurel wreath, below a gold sword and pen, with points downward, the tip ends of the wreath passing under the sword blade and pen quill FOREWORD The Judge Advocate General's School soon begins its twenty second year on the Grounds of the University of Virginia. In these years "the Home of the Military Lawyer" has consistently sought to serve the Army Lawyer in the field-by preparing him in our resident courses, keeping him supplied with the most recent legal information in a clear and concise form, and providing good quality continuing legal education programs both in the resident short courses and in our nonresident extension courses. But our active lawyer is only one part of our Corps and the School has likewise become the home for the lawyers in the Army Reserve and the Army and Air National Guard-the other two vital parts of our Army. -

White House Central Files, Staff Member and Office Files: Susan

CONTAINER NO. CONTENTS CORRESPONDENCE FILE, 1970-74 1 Thank-You Letters [2/70-7/70] Thank-Yous--1970 C[oralJS[chmidJ--Thank You's--1971 C[oralJS[chmid] Thank Yous 1972 October 1970-February 1972 Stephanie Wilson [1 of 3J October 1970-February 1972 Stephanie wilson [2 of 3] October 1970-February 1972 Stephanie Wilson [3 of 3] ~tephan ie Carbons [February 1972-August 1972] [1 of 2] Stephan ie Carbons [February 1972-August 1972] [2 of 2] 2 October 1970-July 1972 TN, JNE, DOE [1 of 3] October 1970-July 1972 TN, JNE, DOE [2 of 3] October 1970-July 1972 TN, JNE, DOE [3 of 3] Carbons Alphabetically (9/1/72-Election) [1 of 6] Carbons Alphabetically (9/1/72-E1ection) [2 of 6] [A-C) Carbons Alphabetically (9/1/72-Election) [3 of 6] [D-H) Carbons Alphabetically (9/1/72-E1ection) [4 of 6] [ I-M] Carbons Alphabetically (9/1/72-E1ection) [5 of 6] [N-R] Carbons Alphabetically (9/1/72-Election) [6 of 6] [S-Z) Carbons Alphabetically (Election-Inauguration) [1 of 4] Carbons Alphabetically (Election-Inauguration) [2 of 4] [A- C) Carbons Alphabetically (Election-Inauguration) [3 of 4] [O- M] Carbons Alphabetically (Election-Inauguration) [4 of 4] [N- Z] 3 Carbons Alphabetically (Inaug .-6/1/73) A-M [1 of 5] [A-B) Carbons Alphabetically (Inaug. -6/1/73) A-C-t [2 of 5] [C-D] Carbons Alphabetically (Inaug .-6/1/73) A-M [3 of 5] [E-G] Carbons Alphabetically (Inaug. -6/1/73) A-I-t [4 of 5] [H-K] Carbons Alphabetically (Inaug .-6/1/73) A-M [5 of 5] [L-!wJ] Carbons Alphabetically (Inaug.-6/l/73) N-Z [1 of 3] [N-Q] Carbons Alphabetically (Inaug.-6/1/73) N-Z [2 of 3] [R-S] Carbons Alphabetically (Inaug .-6/1/73) l-l-Z [3 of 3] IT-Z 1 Memos, Anne Armstrong (& [Pam] Powell) Memos, Jim Cavanaugh Memos, Clem Conger Memos, r-1ike Farrell/Bob Genader 4 Memos, Barbara Flynn (& [Eliska] Hasek) Memos, Gift Unit ~emos, William Henkel Memos, Miscellaneous Memos, National Security Council Memos, David Parker (& [Terrence] O'Donnell) ~emos, Coral Schmid Memos, \'lilliam Timmons C[oral]S[chmid]--Reading File 1970 Travel Vouchers C[oral]S[chmid] 8 CONTAINER NO. -

AFT Local 1295: Wayne State University Federation of Teachers

WAYNE STATE UNIVERSITY FEDERATION OF TEACHERS COLLECTION Papers, 1957-1974 2 linear feet 1 magnetic-recording tape Accession Number 688 L.C. Number The papers of the Wayne State University Federation of Teachers, Local 1295 of the American Federation of Teachers, were deposited with the Archives of Labor History and Urban Affairs in December of 1972, by Richard R. Hixson; with additional material being deposited in November of 1974, by Robert R. Kunnath. Wayne State University Federation of Teachers, Local 1295 of the American Federation of Teachers, was organized in 1957. In the spring of 1972 it lost the collective bargaining representation election to the American Association of University Professors. Thereupon Local 1295 became a "loyal opposition," a role, which amid declining membership, was maintained until late 1974 when the local was disbanded. Some prominent officers of Local 1295 were Secretary Arthur Antisdel, President August Kerber, Treasurer Robert R. Kunnath, President Max Mark, Secretary Richard M. Spector, Treasurer and President Maurice (Maury) Waters, and President William Wattenberg. The papers of Local 1295 pertain mainly to internal union organization and activities. Also included are documents which help clarify union positions regarding both social and political events of the years 1957-1974. Important subjects covered in the collection are; AFSCME Local 1479 strike in October of 1969, at Wayne State University Collective bargaining Michigan Employment Relations Commission (MERC) collective bargaining representation election held in March, 1972 Faculty salaries, layoffs, tenure Teacher unionism Among the correspondents are; (see index at end of guide for locations) Arthur Antisdel Rev. Cecil L. Franklin Jerome Brooks George Gullen -2- WSUFT local 1295 Correspondents continued: Richard A. -

December 1, 1972 Issue (Dig120172.Pdf)

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION ~!!:W~ IDil@!!:~1r (Pr.parocl by the SEC OHI •• of Public Infomtotion) (Issue No. 72-230) FO R RELEASE _~De~c::!:e~mb~e~r~l.L.'--'1.....9~7"-2 _ DECISION IN ADMINISTRATIVE PROCEEDIH; NASD SANCIIONS AGAINST GEOlIGE ALLEN TALIAFERRO AND GERALD OSTROW SET ASIDE. In a decision announced today in proceedings for review of disciplinary action taken by the NASD, the SEC set aside the sanctions imposed by the NASD on George Allen Taliaferro and Gerald Ostrow, of Beverly Hills, Calif., principals of Union Webster Securities Corporation, a former member of the NASD. The sanctiona had been imposed on the basis of the KASDts findings that the firm had failed to comply with the Commission's net capital rule as of Hay IS, 1970. The Commission foun~however, that prior to that date the firm had ceased doing business, and noted that a net capital violation entails the effecting of securities transactions with inadequate net capital. (ReI. 34-9871) NEW RULES AND RULE PROPOSALS PROPOSED APPLICATION UVISION. The SEC today proposed adoption of Rule 0-2(g) and amendment of Rule 0-5, both under the Investment Company Act of 1940. Proposed Rule 0-2(g) would formally require submission of a proposed notice for applications for an order under any provision of the Investment Company Act. The proposed amendment of Rule 0-5 would delete present subsection (b) of that Rule. This indicates that notices of such applications should specify a date when an order disposing of the matter will be issued, unless the Commiasion orders a hearing on the matter prior to that date. -

Box Folder Date Extent Presidential Correspondence 1969-1974 748

Box Folder Date Extent Presidential Correspondence 1969-1974 748 AFGHANISTAN Mohammad Daoud [October-November 1973] ALGERIA Col Houari Boumediene October 1970-April 1973] ARGENTINA Pres Lanusse [October 1971-May 1973] AUSTRALIA Prime Minister Gorton Corres. [June 1969-April 1970] AUSTRALIA Prime Minister McMahon [May 1971-March 1973] AUSTRALIA: PM E. Gough [December 1972-August 1973] AUSTRIA CHANCELLOR: Kreisky, Bruno [June 1972] BAHRAIN Shaykh Isa bin Salmar Al-Khalita [December 1971] BANGLADESH Prime Minister Mujibur Rahman [February 1972-July 1974] 749 Belgium KING BAUDOUIN [June 27, 1974] President Banzer (Bolivia) [1971-1973] Brazil President Gen. Ernesto Geisel President of Brazil General Emilio Garrastazu Medici [1972-1973] BURMA General Ne Win Corres. [1971-1972] CAMBODIA Prince Sihanouk Corres. [1969-1974] Cambodia MATAK, SIRIK CORRES. [1970-1971] CAMBODIA Lon Nol, Prime Minister 1970 Box Folder Date Extent Presidential Correspondence 1969-1974 749 Cambodia: President Marshal Lon Nol 1971 750 CAMBODIA President, Marshal Lon Nol 1972 CANADA Trudeau corres. [1969-1973] CEYLON Prime Minister Senanayake Corres. [1970] 751 CHAD Pres. Francois Tombalbaye [April 1970-December 1972] CHILE Pres. Allende Corres. [December 8, 1971] REPUBLIC OF CHINA corres. Pres. Chaing Kai-shek November 1969-March 1973] COLOMBIA CARLOS LLERAS CORRES. Republic of Colombia Bogota, Dr. Misael Pastrana Borrero (President) CONGO (Kinshasa) President Mobutu Corres. COSTA RICA Trejos corres. Jose Figueres Ferrer (Pres) Costa Rica, San Jose DOMINICAN REPUBLIC Pres Joaquin Balaguer President of Ecuador Jose Maria Velasco Ibarra President of Ecuador Guillermo Antonio Rodriguez Lara EGYPT President Sadat ETHIOPIA Selassie corres. Box Folder Date Extent Presidential Correspondence 1969-1974 751 FRANCE P.M. Chaban-Delmas Corres. -

Country Files - Africa 735 ALGERIA Vol

Country Files - Africa 735 ALGERIA Vol. I [1969-1974] BOTSWANA Vol. I [1969-1972] BURUNDI Vol. I [1972-1974] CAMEROON Vol. I [1969-1971] 736 CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC Vol. I [September 1971-October 1973] CHAD Vol. I [December 1969-July 1974] DAHOMEY Vol. I [February 1969-April 1974] ETHIOPIA Vol. I January 1969-December 1971 Box Folder Date Extent Country Files - Africa 736 ETHIOPIA Vol. II January 1972 737 GABON Vol. I [April 1969-May 1974] GAMBIA Vol. I GHANA Vol. I [February 1969-March 1974] GUINEA Vol. I [May 1969-April 1974] IVORY COAST Vol. I [March 1969-March 1974] 738 KENYA Vol. I LESOTHO Vol. I LIBERIA Vol. I LIBYA Vol. I June 1969-June 1970 739 LIBYA Vol. II July 1970 LIBYAN RECCE FLIGHTS MALAGASY REPUBLIC Vol. I 740 MALAWI Vol. I [July 1970-April 1973] MALI Vol. I [April 1969-September 1971] MAURITANIA Vol. I [January 1970-January 1973] MAURITIUS Vol. I [1969-August 1971] Box Folder Date Extent Country Files - Africa 740 MOROCCO VOL I 1969-August 1971 MOROCCO VOL II from September 1971 741 NAMIBIA (SOUTH WEST AFRICA) [January 1970-September 1971] NIGER [January-June 1974] NIGERIA Vol. I [January-May 1969] NIGERIA Vol. II October 1969 [1 of 2] NIGERIA Vol. II October 1969 [2 of 2] 742 NIGERIA Vol III November 1969-February 28, 1970 [1 of 2] NIGERIA Vol III November 1969-February 28, 1970 [2 of 2] NIGERIA VOL IV March 1, 1970 [1 of 2] NIGERIA VOL IV March 1, 1970 [2 of 2] 743 RHODESIA VOL I 1969-1970 RHODESIA VOL 2 1971- RWANDA Vol.