Bengal Distriot Gazetteers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BPL NIC 29.06.2020. FINAL 04-07-2020.Xlsx

1 - 11 DRDA Recruitment for Account Assistant Matric Intermediate or Equivalent Graduation Other Qualification Type 1 Other Qualification Type 2 Weightage Weightage Weightage Weightage sL fatheR Weightage Total Weightage Weightage Total peRsoNaL id Name doB Gender Category PH PH % Correspondance Address Point Point Point Point Total Point RemaRks No. Name (-) Percentage Point(50%) (-) Percentage (15%) (25%) (10%) (10%) School/Bo Obtained Board/ Obtained Graduation Branch/ University/Coll Obtained Total Obtained Total Obtained Total Merit Sl. No Sl. Merit Total Marks Percentage Stream Stream Name Total Marks Percentage Percentage Type stream university Percentage Type stream universit Percentage ard Marks University Marks Type Subject ege Marks Marks Marks Marks Marks Marks y 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 AT KUSAIYA POST REMBA PANCHAYAT JAC V B U ACCOUN n o u अगले म 1 40 DRDA90001000 MD DAUD HUSSAIN JAKIR HUSSAIN 4/29/1995 Male BC1 No 0 385 500 77 11.55 Commerce accountancy JAC RANCHI 361 500 72.2 18.05 BCom 607 800 75.88 75.88 37.94 m com 417 800 52.13 52.13 5.213 0 72.753 SHALI PS HIRODIH DIST RANCHI HAZARIBAG TANCY patna के िलए यो GIRIDIH JHARKHAND VILLAGE-GIRIDIH, PO- VBU SUDHIR KUMAR SIMARIYA PS- DHANWAR JAC VBU COMME अगले म 2 68 DRDA90001894 PAWAN KUMAR 11/15/1994 Male GEN No 0 365 500 73 10.95 Commerce COMMERCE JAC RANCHI 313 500 62.6 15.65 BCom 545 800 68.13 68.13 34.065 M COM HAZARIB 1170 1600 73.13 73.13 7.313 0 67.978 -

Academic Course Prospectus for the Session 2012-13

PROSPECTUS 2012-13 With Application Form for Admission Secondary and Senior Secondary Courses fo|k/kue~loZ/kuaiz/kkue~ NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF OPEN SCHOOLING (An autonomous organisation under MHRD, Govt. of India) A-24-25, Institutional Area, Sector-62, NOIDA-201309 Website: www.nios.ac.in Learner Support Centre Toll Free No.: 1800 180 9393, E-mail: [email protected] NIOS: The Largest Open Schooling System in the World and an Examination Board of Government of India at par with CBSE/CISCE Reasons to Make National Institute of Open Schooling Your Choice 1. Freedom To Learn With a motto to 'reach out and reach all', NIOS follows the principle of freedom to learn i.e., what to learn, when to learn, how to learn and when to appear in the examination is decided by you. There is no restriction of time, place and pace of learning. 2. Flexibility The NIOS provides flexibility with respect to : • Choice of Subjects: You can choose subjects of your choice from the given list keeping in view the passing criteria. • Admission: You can take admission Online under various streams or through Study Centres at Secondary and Senior Secondary levels. • Examination: Public Examinations are held twice a year. Nine examination chances are offered in five years. You can take any examination during this period when you are well prepared and avail the facility of credit accumulation also. • On Demand Examination: You can also appear in the On-Demand Examination (ODES) of NIOS at Secondary and Senior Secondary levels at the Headquarter at NOIDA and All Regional Centres as and when you are ready for the examination after first public examination. -

Village and Town Directory, Puruliya, Part XII-A , Series-26, West Bengal

CENSUS OF INDIA 1991 SERIES -26 WEST BENGAL DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK PART XII-A VILLAGE AND TOWN DIRECTORY PURULIYA DISTRICT DIRECTORATE OF CENSUS OPERATIONS WEST BENGAL Price Rs. 30.00 PUBLISHED BY THE CONTROLLER GOVERNMENT PRINTING, WEST BENGAL AND PRINTED BY SARASWATY PRESS LTD. 11 B.T. ROAD, CALCUTTA -700056 CONTENTS Page No. 1. Foreword i-ii 2. Preface iii-iv 3. Acknowledgements v-vi 4. Important Statistics vii-viii 5. Analytical note and Analysis of Data ix-xxxiii Part A - Village and Town Directory 6. Section I - Village Directory Note explaining the Codes used in the Village Directory 3 (1) Hura C.D. Block 4-9 (a) Village Directory (2) Punch a C.D. Block 10-15 (a) Village Directory (3) Manbazar - I C.D. Block 16 - 29 (a) Village Directory (4) Manbazar -II C.D. Block 30- 41 (a) Village Directory (5) Raghunathpur - I C.D. Block 42-45 (a) Village Directory (6) Raghunathpur - II C.D. Block 46 - 51 (a) Village Directory (7) Bagmundi C.D. Block 52- 59 (a) Village Directory (a) Arsha C.D. Block 60-65 (a) Village Directory (9) Bundwan C.D. Block 66-73 (a) Village Directory (10) Jhalda -I C.D. Block 74 - 81 (a) Village Directory (11) Jhalda -II C.D. Block 82-89 (a) Village Directory (12) Neturia C.D. Block 90-95 (a) Village Directory (13) Kashipur C.O. Block 96 -107 (a) Village Directory (14) Santuri C.D. Block 108-115 (a) Village Directory (15) Para C.O. Block 116 -121 (a) Village Directory Page No. (16) Purulia -I C.D. -

Jharkhand.Pdf

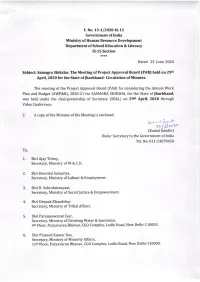

F. No. 13-1l2020-IS-15 Government of India Ministry of Human Resource Development Department ofSchool Education & Literacy IS-15 Section **** Dated 22 June, 2020 Subiect: Samagra Shiksha: The Meeting of Proiect Approval Board (PAB) held on 29ttt April, 2020 for the State oflharkhand- Circulation of Minutes. The meeting of the Project Approval Board (PAB) for considering the Annual Work Plan and Budget (AWP&B),2020-?1 for SAMAGRA SHIKSHA, for the State of fharkhand, was held under the chairpersonship of Secretary (SE&L) on 296 April, 2020 through Video Conference. 2. A copy ofthe Minutes ofthe Meeting is enclosed. aLl6lwaPw'- "/----4(Kamal Gandhi) Under Secretary to the Government of lndia Tel. No. 011.-23070450 To, 1. Shri Aiay Tirkey, Secretary, Ministry of W & C.D. 2 Shri Heeralal Samariya, Secretary, Ministry of Labour & Employment. Shri R. Subrahmanyam, Secretary, Ministry of Social lustice & Empowerment. 4 Shri Deepak Khandekar Secretary, Ministry of Tribal Affairs 5 Shri Parameswaran Iyer, Secretary, Ministry of Drinking Water & Sanitation, 4th Floor, Paryavaran Bhavan, CGO Complex, Lodhi Road, New Delhi-110003. 6 Shri Pramod Kumar Das, Secretary, Ministry of Minority Affairs, 11s Floor, Paryavaran Bhavan, CGO Complex, Lodhi Road, New Delhi-110003. 7 Ms. Shakuntala D. Gamlin, Secretary, Department of Empowerment of persons With Disabilities, Ministry of Social Justice & Empowerment. I Dr. Poonam Srivastava, Dy. Adviser (EducationJ, NITI Aayog. 9 Prof. Hrushikesh Senapaty Director, NCERT. 10 Prof. N.V. Varghese, Vice Chancellor, NIEPA. 11. Chairperson, NCTE, Hans Bhawan, Wing II, 1 Bahadur Shah Zafar Marg, New Delhi - tL0002. 1.2 Prof. Nageshwar Rao, Vice Chancellor, IGN0U, Maidan Garhi, New Delhi. -

Download Brochure

ESTD.-1948 JAGANNATH KISHORE COLLEGE PURULIA (Undergraduate & Postgraduate) Affiliated to SIDHO-KANHO-BIRSHA University Formerly affiliated to The University of Burdwan P.O. & Dist.: Purulia. PIN: 723101 e-mail: [email protected] / [email protected] website: www.jkcprl.ac.in Ph. : (03252) 222416 / 228744 Fax : (03252) 228744 NAAC Accredited (2nd Cycle) PROSPECTUS - 2017 [ 1 ] UNIVERSITY (B.U.) TOPPERS FROM OUR COLLEGE UPDATED UPTO 2013 Sl. Passing Name of the Student Subject No. Year 1. Sri Gopal Karmakar Mathematics Hons. 1977 2. Sri Debabrata Ghosh History Hons. 1985 3. Sri Bidyapati Kumar Mathematics Hons. 1985 4. Sri Sujit Kumar Khan Mathematics Hons. 1987 5. Sri Ganesh Chandra Gorain Mathematics Hons. 1990 6. Sri Apurba Saha English Hons. 1993 7. Smt. Suprabha Misra Mathematics Hons. 1994 8. Smt. Arpita Dey Mathematics Hons. 1996 9. Sri Angsuman Kar English Hons. 1997 10. Sri Sahadeb Pradhan Chemistry Hons. 1997 11. Sri Shyam Singh Political Science Hons. 1997 12. Sri Sunil Kothari Accountancy Hons. 1998 13. Smt. Batasi Bandyopadhyay Mathematics Hons. 2001 14. Smt. Moumita Dubey Geology Hons. 2002 15. Sri Subrata Duari Philosophy Hons. 2002 16. Sri Kirity Mahanty Mathematics Hons. 2003 17. Sri Vivek Kumar Hansia Accountancy Hons. 2007 18. Smt. Khusbu Jhunjhunwala Accoutancy Hons. 2008 19. Sri Rajdeep Das Computer Science Hons. 2010 20. Smt. Sanchita Chowdhury Mathematics M.Sc. 2011 21. Smt. Rinku Kumar Education Hons. 2012 22. Smt. Santana Majee Mathematics Hons. 2013 ACHIEVEMENT IN GAMES & SPORTS :- Several times champion in Sports Meet in District Football Sports Champion (DPI) Several times champion in Football Championship in District Football Sports Champion (DPI) Sri Arvind Singh, Champion in State Level Sports (DPI) in 2011 [ 2 ] UNIVERSITY (S.K.B.U.) TOPPERS FROM OUR COLLEGE UPDATED UPTO 2015 2014 Sl. -

Journal of History

Vol-I. ' ",', " .1996-97 • /1 'I;:'" " : ",. I ; \ '> VIDYASAGAR UNIVERSITY Journal of History S.C.Mukllopadhyay Editor-in-Chief ~artment of History Vidyasagar University Midnapore-721102 West Bengal : India --------------~ ------------ ---.........------ I I j:;;..blished in June,1997 ©Vidyasagar University Copyright in articles rests with respective authors Edi10rial Board ::::.C.Mukhopadhyay Editor-in-Chief K.K.Chaudhuri Managing Editor G.C.Roy Member Sham ita Sarkar Member Arabinda Samanta Member Advisory Board • Prof.Sumit Sarkar (Delhi University) 1 Prof. Zahiruddin Malik (Aligarh Muslim University) .. <'Jut". Premanshu Bandyopadhyay (Calcutta University) . hof. Basudeb Chatterjee (Netaji institute for Asian Studies) "hof. Bhaskar Chatterjee (Burdwan University) Prof. B.K. Roy (L.N. Mithila University, Darbhanga) r Prof. K.S. Behera (Utkal University) } Prof. AF. Salauddin Ahmed (Dacca University) Prof. Mahammad Shafi (Rajshahi University) Price Rs. 25. 00 Published by Dr. K.K. Das, Registrar, Vidyasagar University, Midnapore· 721102, W. Bengal, India, and Printed by N. B. Laser Writer, p. 51 Saratpalli, Midnapore. (ii) ..., -~- ._----~~------ ---------------------------- \ \ i ~ditorial (v) Our contributors (vi) 1-KK.Chaudhuri, 'Itlhasa' in Early India :Towards an Understanding in Concepts 1 2.Bhaskar Chatterjee, Early Maritime History of the Kalingas 10 3.Animesh Kanti Pal, In Search of Ancient Tamralipta 16 4.Mahammad Shafi, Lost Fortune of Dacca in the 18th. Century 21 5.Sudipta Mukherjee (Chakraborty), Insurrection of Barabhum -

THE WEST BENGAL COLLEGE SERVICE COMMISSION Vacancy Status (Tentative) for the Posts of Assistant Professor in Government-Aided Colleges of West Bengal (Advt

THE WEST BENGAL COLLEGE SERVICE COMMISSION Vacancy Status (Tentative) for the Posts of Assistant Professor in Government-aided Colleges of West Bengal (Advt. No. 1/2018) Bengali UR OBC-A OBC-B SC ST PWD 43 13 1 30 25 6 Sl No College University UR 1 Bankura Zilla Saradamoni Mahila Mahavidyalaya 2 Khatra Adibasi Mahavidyalaya. 3 Panchmura Mahavidyalaya. BANKURA UNIVERSITY 4 Pandit Raghunath Murmu Smriti Mahavidyalaya.(1986) 5 Saltora Netaji Centenary College 6 Sonamukhi College 7 Hiralal Bhakat College 8 Kabi Joydeb Mahavidyalaya 9 Kandra Radhakanta Kundu Mahavidyalaya BURDWAN UNIVERSITY 10 Mankar College 11 Netaji Mahavidyalaya 12 New Alipore College CALCUTTA UNIVERSITY 13 Balurghat Mahila Mahavidyalaya 14 Chanchal College 15 Gangarampur College 16 Harishchandrapur College GOUR BANGA UNIVERSITY 17 Kaliyaganj College 18 Malda College 19 Malda Women's College 20 Pakuahat Degree College 21 Jangipur College 22 Krishnath College 23 Lalgola College KALYANI UNIVERSITY 24 Sewnarayan Rameswar Fatepuria College 25 Srikrishna College 26 Michael Madhusudan Memorial College KAZI NAZRUL UNIVERSITY (ASANSOL) 27 Alipurduar College 28 Falakata College 29 Ghoshpukur College NORTH BENGAL UNIVERSITY 30 Siliguri College 31 Vivekananda College, Alipurduar 32 Mahatma Gandhi College SIDHO KANHO BIRSHA UNIVERSITY 33 Panchakot Mahavidyalaya 34 Bhatter College, Dantan 35 Bhatter College, Dantan 36 Debra Thana Sahid Kshudiram Smriti Mahavidyalaya VIDYASAGAR UNIVERSITY 37 Hijli College 38 Mahishadal Raj College 39 Vivekananda Satavarshiki Mahavidyalaya 40 Dinabandhu -

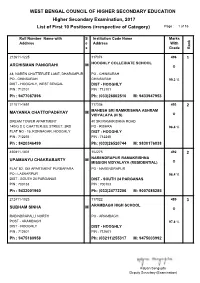

Irrespective of Category) Page : 1 of 16

WEST BENGAL COUNCIL OF HIGHER SECONDARY EDUCATION Higher Secondary Examination, 2017 List of First 10 Positions (irrespective of Category) Page : 1 of 16 Roll Number Name with S Institution Code Name Marks Address e Address With x Grade Rank 212611-1225 117074 496 1 HOOGHLY COLLEGIATE SCHOOL ARCHISMAN PANIGRAHI M O 48, NAREN CHATTERJEE LANE, DHARAMPUR PO - CHINSURAH PO - CHINSURAH CHINSURAH 99.2 % DIST - HOOGHLY, WEST BENGAL DIST - HOOGHLY PIN : 712101 PIN : 712101 Ph : 9477087896 Ph: (033)26802510 M: 9433947953 211011-1691 117238 492 2 MAYANKA CHATTOPADHYAY M MAHESH SRI RAMKRISHNA ASHRAM VIDYALAYA (H S) O DREAM TOWER APARTMENT 40 SRI RAMKRISHNA ROAD 140/G S C CHATTERJEE STREET, 3RD PO - RISHRA 98.4 % FLAT NO - 15, KONNAGAR, HOOGHLY DIST - HOOGHLY PIN : 712235 PIN : 712248 Ph : 8420346499 Ph: (033)26520744 M: 9830176838 450811-1801 102275 492 2 UPAMANYU CHAKRABARTY M NARENDRAPUR RAMAKRISHNA MISSION VIDYALAYA (RESIDENTIAL) O FLAT B2, OM APARTMENT PURBAPARA PO - NARENDRAPUR PO - LASKARPUR 98.4 % DIST - SOUTH 24 PARGANAS DIST - SOUTH 24 PARGANAS PIN : 700153 PIN : 700103 Ph : 9432001960 Ph: (033)24772206 M: 9007085285 212411-1023 117022 489 3 ARAMBAGH HIGH SCHOOL SUBHAM SINHA M O RABINDRAPALLI NORTH PO - ARAMBAGH POST - ARAMBAGH 97.8 % DIST - HOOGHLY DIST - HOOGHLY PIN : 712601 PIN : 712601 Ph : 9475180958 Ph: (03211)255317 M: 9475003992 Kalyan Sengupta Deputy Secretary (Examination) WEST BENGAL COUNCIL OF HIGHER SECONDARY EDUCATION Higher Secondary Examination, 2017 List of First 10 Positions (irrespective of Category) Page : 2 of 16 Roll -

Education General Sc St Obc(A) Obc(B) Ph/Vh Total Vacancy 37 44 19 16 17 4 137 General

EDUCATION GENERAL SC ST OBC(A) OBC(B) PH/VH TOTAL VACANCY 37 44 19 16 17 4 137 GENERAL Sl No. University College Total 1 RAJ NAGAR MAHAVIDYALAYA 1 BURDWAN UNIVERSITY 2 SWAMI DHANANJAY DAS KATHIABABA MV, BHARA 1 3 AZAD HIND FOUZ SMRITI MAHAVIDYALAYA 1 4 BARUIPUR COLLEGE 1 5 DHOLA MAHAVIDYALAYA 1 6 HERAMBA CHANDRA COLLEGE 1 7 CALCUTTA UNIVERSITY MAHARAJA SRIS CHANDRA COLLEGE 1 8 SERAMPORE GIRLS' COLLEGE 1 9 SIBANI MANDAL MAHAVIDYALAYA 1 10 SONARPUR MAHAVIDYALAYA 1 11 SUNDARBAN HAZI DESARAT COLLEGE 1 12 GANGARAMPUR COLLEGE 1 13 GOURBANGA UNIVERSITY NATHANIEL MURMU COLLEGE 1 14 SOUTH MALDA COLLEGE 1 15 DUKHULAL NIBARAN CHANDRA COLLEGE 1 16 HAZI A. K. KHAN COLLEGE 1 17 KALYANI UNIVERSITY NUR MOHAMMAD SMRITI MAHAVIDYALAYA 1 18 PLASSEY COLLEGE 1 19 SUBHAS CHADRA BOSE CENTENARY COLLEGE 1 20 CLUNY WOMENS COLLEGE 1 21 LILABATI MAHAVIDYALAYA 1 NORTH BENGAL UNIVERSITY 22 NAKSHALBARI COLLEGE 1 23 RAJGANJ MAHAVIDYALAYA, RAJGANJ 1 24 ARSHA COLLEGE 1 SIDHO KANHO BIRSA UNIVERSITY 25 KOTSHILA MAHAVIDYALAYA 1 26 BHATTER COLLEGE 1 27 GOURAV GUIN MEMORIAL COLLEGE 1 28 PANSKURA BANAMALI COLLEGE 1 VIDYASAGAR UNIVERSITY 29 RABINDRA BHARATI MAHAVIDYALAYA 1 30 SIDDHINATH MAHAVIDYALAYA 1 31 SUKUMAR SENGUPTA MAHAVIDYALAYA 1 32 BARRAKPORE RASHTRAGURU SURENDRANATH COLLEGE 1 33 KALINAGAR MV 1 34 MAHADEVANANDA MAHAVIDYALAYA 1 WEST BENGAL STATE UNIVERSITY 35 NETAJI SATABARSHIKI MAHABIDYALAYA 1 36 P.N.DAS COLLEGE 1 37 RISHI BANKIM CHANDRA COLLEGE FOR WOMEN 1 OBC(A) 1 HOOGHLY WOMEN'S COLLEGE 1 BURDWAN UNIVERSITY 2 KABI JOYDEB MAHAVIDYALAYA 1 3 GANGADHARPUR MAHAVIDYALAYA -

49107-006: West Bengal Drinking Water Sector Improvement Project

INITIAL ENVIRONMENTAL EXAMINATION UPDATED PROJECT NUMBER: 49107-006 NOVEMBER 2020 IND: WEST BENGAL DRINKING WATER SECTOR IMPROVEMENT PROJECT – BULK WATER SUPPLY FOR TWO BLOCKS IN BANKURA (Package DWW/BK/01) – PART A PREPARED BY PUBLIC HEALTH ENGINEERING DEPARTMENT, GOVERNMENT OF WEST BENGAL FOR THE ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK ABBREVIATIONS ADB - Asian Development Bank CBO - Community-Based Organization CPCB - Central Pollution Control Board CTE - Consent to Establish CTO - Consent to Operate DBO - Design, Build and Operate DDR - Due Diligence Report DMS - Detailed Measurement Survey DSC - District Steering Committee DSISC - Design, Supervision and Institutional Support Consultant EAC - Expert Appraisal Committee EHS - Environmental, Health and Safety EIA - Environmental Impact Assessment EMP - Environmental Management Plan ESSU - Environment and Social Safeguard Unit FGD - Focus Group Discussion GLR - Ground Level Reservoir GoWB - Government of West Bengal GRC - Grievance Redress Committee GRM - Grievance Redress Mechanism HIDCO - Housing and Infrastructure Development Corporation HSGO - Head, Safeguards and Gender Officer IBPS - Intermediate Booster Pumping Station IEE - Initial Environmental Examination IPP - Indigenous People Plan IWD - Irrigation and Waterways Department MOEFCC - Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change NGO - Nongovernment Organization NOC - No Objection Certificate PHED - Public Health Engineering Department PIU - Project Implementation Unit PMC - Project Management Consultant PMU - Project Management Unit PPTA -

A Case Study of Different Folk Cultures of Purulia: a Study of Folk Songs and Dances and the Problems at “Baram” Village, Purulia, West Bengal, India

Reinvention International: An International Journal of Thesis Projects and Dissertation Vol. 1, Issue 1 - 2018 A CASE STUDY OF DIFFERENT FOLK CULTURES OF PURULIA: A STUDY OF FOLK SONGS AND DANCES AND THE PROBLEMS AT “BARAM” VILLAGE, PURULIA, WEST BENGAL, INDIA SANTANU PANDA* CERTIFICATE This is to certify that Santanu Panda has completed his general work for partial fulfilment of M.A 3rd semester bearing Roll- 53310016 No-0046 Session- 2016-2017 of Sidho-Kanho-Birsha-University, carried out his field work at Baram village of Purulia district under supervision of Dr Jatishankar Mondal of Department of English. This is original and basic research work on the topic entitled A Case Study of Different FOLK CULTURES OF Purulia: A study of FOLK SONGS AND DANCES AND THE PROBLEMS AT “BARAM” VILLAGE He is very energetic and laborious fellow as well as a good field worker in Field study. Faculty of the Department of English ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I, Santanu Panda a student of semester III, Department of English, Sidho-Kanho-Birsha University, Purulia, acknowledge all my teachers and guide of the research project who help me to complete this Outreach Program with in time I, acknowledge Dr. Jatishankar Mondal, Assistant Professor, from the core of my heart because without his guidance and encouragement, this work is not possible. I also acknowledge my group members (Raju Mahato, Ramanath Mahato, Nitai Mondal, Nobin Chandra Mahato, Pabitra Kumar and Saddam Hossain) for their participation and the other group also for their support. My sincere thanks also go to the respondents, that is, the villagers, the Chhau club and Jhumur club in Baram for their sincere co-operation during the data collection. -

CPI(Maoist) Spokesperson Comrade Azad on 2009 Lok Sabha Elections

MAOIST INFORMATION BULLETIN - 7 April 15, 2009 In this issue News from the battle field From the news papers Interview with CPI(Maoist) Spokesperson Comrade Azad on 2009 Lok Sabha elections Press statements Maoists Avenge Singaram Massacre News from Battle-field Maoist guerrillas wipe out 15 policemen in Maharashtra in a daring day-light ambush In one of the most daring attacks by Maoist guerrillas on the mercenary police forces in Maharashtra, 15 policemen including a sub-inspector were wiped out in the jungles of Markegaon village in Dhanora tehsil of Gadchiroli district, around 300 km from Nagpur, on the morning of February 1. After the successful ambush the Maoists retreated without any casualty. Markegaon is close to the Gyrapatti-Sawargaon road and around eight km from the Gyarapatti Katgul police outpost, which is along the Maharashtra-Chhattisgarh border. The police sub-inspector killed has been identified as Bhupendra Gudgekar of Amravati. A number of cops took bullet injuries. A sources in Gadchiroli police said, ‘’The police party was heading towards Markegaon, some 45 km from Dhanora, to investigate into the January 30 arson committed by the Maoists, when the rebels attacked them. The police party was ambushed in such a manner that all the members, including head PSI Gudgekar, were killed on spot.’’ The ambush took place at around 11.15 am. When a relief party reached the area to rescue the first team, it, too, was attacked, preventing immediate reinforcement. But by late in the afternoon on 1st, more than 3,000 police personnel were sent to Gadchiroli.