January 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EMP 2148 Sanatkumarguchhait.Pdf

BIODATA 1. Name (in block letters) : DR. SANAT KUMAR GUCHHAIT 2. (a) Present Position : ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR Department of Geography, The University of Burdwan (b) Address for communication : DEPARGMENT OF GEOGRAPHY (in block letters) THE UNIVERSITY OF BURDWAN GOLAPBAG, PO – RAJBATI, BURDWAN – 713104 3. Permanent Address (in block letters) : C/O, BIPUL KUMAR GUCHHAIT VILL – HARIPUR, PO – MADHABPUR DIST. – EAST MIDNAPUR, PIN – 721626 4. Date of Birth : 30TH DECEMBER, 1968 5. Name of Father/Mother : BIPUL KUMAR GUCHHAIT 6. Nationality : INDIAN 7. Marital Status : (a) Single/Married : MARRIED (b) Name of Spouse : SMT. SRABANI GUCHHAIT (GUPTA) 8. Whether belonging to Scheduled Caste/Scheduled Tribe: NO 9. Date of Registration for Doctoral Degree (Ph.D.) : Ph.D. 19.04.2002 10. Research degree awarded : Year : 2005 (Ph.D.) University : THE UNIVERSITY OF BURDWAN Title of Thesis: POPULATION EXPLOSION IN WEST BENGAL: AN ENQUIRY INTO SOME ASPECTS OF ITS GEOGRAPHICAL REALITY 11. Publications : (a) Total number of Papers in recognised research journals : 19 (b) Books/Monographs etc. : Books – 2 12. Research Experience: (See Annexure – I) (a) Topic of research: Social and Cultural Issues, Envionmental Issues, Geography of Education, Poverty Ecology and Development (b) Place of research: Rarh Bengal and South Bengal. (c) Number of years: 10+ (Ten) Years 13. Teaching Experience: (a) Under-graduate Level: College/Univ./Institute/No. of Years/Pass/Hons. 2 YEARS & 9 MONTHS (College / Pass & Hons.) (b) Post-graduate Level: Name of the Univ./Institute 11 YEARS & 10 DAYS (The University of Burdwan) 14. Administrative/Professional Experience: i) Senior most Teacher in the Department (2 years & 9 months) ii) 2 years, Head of the Department, PG Level (B.U.) iii) Member, Paschim Banga Pustak Parsad, 2012. -

Sarbari, PO - Neturia, Dist - Purulia, West Bengal - 723121 Website

PANCHAKOT MAHAVIDYALAYA Sarbari, PO - Neturia, Dist - Purulia, West Bengal - 723121 Website : www.panchakotmv.com SELF STUDY REPORT (Cycle 1) July, 2014 Submitted to: National Assessment and Accreditation Council P.O- Box No. 1075, Nagarbhavi, Bangalore-560 072, India. NAAC ‐ Accreditation Self Study Report 2014 Sl. No. Item Page No. 1 Forwarding Letter for uploading SSR 2 2 Abbreviations used 3 3 Committee for SSR preparation 4 4 Executive Summary & SWOC 5 5 Profile of the College 11 6 Criteria-wise Inputs 23 Criterion I: Curricular Aspects 24 Criterion II: Teaching-Learning and Evaluation 35 Criterion III: Research, Consultancy and Extension 69 Criterion IV: Infrastructure and Learning Resources 89 Criterion V: Student Support and Progression 104 Criterion VI: Governance, Leadership and Management 115 Criterion VII: Innovation and Best Practices 135 7 Evaluative Reports of the Departments 143 8 Declaration by the Head of the Institution 224 9 Annexure 225 1 PANCHAKOT MAHAVIDYALAYA, Sarbari, Neturia, Purulia, W.B. NAAC ‐ Accreditation Self Study Report 2014 2 PANCHAKOT MAHAVIDYALAYA, Sarbari, Neturia, Purulia, W.B. NAAC ‐ Accreditation Self Study Report 2014 ABBREVIATIONS (We Used) AIDS = Acquired Immuno-Deficiency Syndrome APC = Assembled Personal Computer BEUP = Bidhayak Elaka Unnayan Prakalpa BPC = Branded Personal Computer BSNL = Bharat Sanchar Nigam Limited CAS = Career Advancement Scheme DSLR = Digital Single Lens Reflex DST = Department of Science and Technology FC = Financially Challenged GB = Governing Body HED = Higher Education -

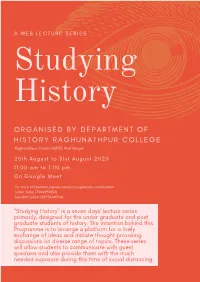

A Web Lecture Series

A W E B L E C T U R E S E R I E S Studying History O R G A N I S E D B Y D E P A R T M E N T O F H I S T O R Y R A G H U N A T H P U R C O L L E G E Raghunathpur, Purulia-723133, West Bengal 25th August to 31st August 2020 11:00 am to 1:00 pm On Google Meet For more information, please contact programme coordinators Sohini Sinha (7044931430) Swadhin Sarkar (9875444304) "Studying History" is a seven days' lecture series primarily, designed for the under graduate and post graduate students of history. The intention behind this Programme is to arrange a platform for a lively exchange of ideas and initiate thought provoking discussions on diverse range of topics. These series will allow students to communicate with guest speakers and also provide them with the much needed exposure during this time of social distancing. A W E B L E C T U R E S E R I E S Studying DAY 1 (25.8.20 Tuesday) History O R G A N I S E D B Y D E P A R T M E N T O F H I S T O R Y R A G H U N A T H P U R C O L L E G E INAUGURAL SESSION Raghunathpur, Purulia-723133, West Bengal (10:30AM - 11:00 AM) Welcome Address Dr.Phalguni Mukhopadhyay (Principal, Raghunathpur college & Chief patron of lecture series program.) Inaugural Address Dr. -

1. New Syllabus for Geography (UG) with Effect from 2016 Onwards (CBCS) 2

1 CHOICE BASED CREDIT SYSTEM (CBCS) SCHEME BY SEMESTERS Department of Geography, Tumkur University Under Graduate Degree Programme 2016 onwards 1. New Syllabus for Geography (UG) with effect from 2016 onwards (CBCS) 2. Course structure. Max Minimum Duration of Marks Passing No. of Semester for marks for Internal Pape teaching Semester Title end Semester Semester assessme r No. hours examinatio end end nt marks per week n examinati examinatio on n ISem Theory Physical Basis of 1.3 4hrs 3hrs 90 32 10 Paper Geography-I ISem Practical- PCT Cartography 4hrs 3hrs 50 20 00 Paper L-1.4 Physical Basis of IISem Theory Geography-II 2.3 4hrs 3hrs 90 32 10 Paper [Atmosphere and Hydrosphere] Weather instruments PCT and study of Indian IISem Practical- 4hrs 3hrs 50 20 00 L-2.4 Daily Paper Weather Reports. IIISem Theory 3.3 Human Geography 4hrs 3hrs 90 32 10 Paper PCT Representation of IIISem Practical- 4hrs 3hrs 50 20 00 L-3.4 Statistical Data Paper IVSem Theory Regional Geography 4.3 4hrs 3hrs 90 32 10 Paper of Karnataka Representations of PCT Landforms and IVSem Practical- 4hrs 3hrs 50 20 00 L-4.4 Study of Paper Topographical Maps. Total 32hrs Geography of India VSem Theory 5.1 Part-I (Compulsory 3hrs 3hrs 90 32 10 Paper Paper) (A) Regional Geography of Asia (Optional Paper) VSem Practical- 5.2 3hrs 3hrs 50 20 00 (B) Geography of Paper Tourism (Optional Paper) 2 Map Projections-I VSem Practical [Cylindrical and 5.3 3hrs 3hrs 90 32 10 Paper Conical groups] VSem Practical- 5.4 Basic Statistics 3hrs 3hrs 50 20 00 Paper Geography of India VISem Theory Part-II [Compulsory 6.1 3hrs 3hrs 90 32 10 Paper paper] (A) Economic Geography of the World. -

Village and Town Directory, Puruliya, Part XII-A , Series-26, West Bengal

CENSUS OF INDIA 1991 SERIES -26 WEST BENGAL DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK PART XII-A VILLAGE AND TOWN DIRECTORY PURULIYA DISTRICT DIRECTORATE OF CENSUS OPERATIONS WEST BENGAL Price Rs. 30.00 PUBLISHED BY THE CONTROLLER GOVERNMENT PRINTING, WEST BENGAL AND PRINTED BY SARASWATY PRESS LTD. 11 B.T. ROAD, CALCUTTA -700056 CONTENTS Page No. 1. Foreword i-ii 2. Preface iii-iv 3. Acknowledgements v-vi 4. Important Statistics vii-viii 5. Analytical note and Analysis of Data ix-xxxiii Part A - Village and Town Directory 6. Section I - Village Directory Note explaining the Codes used in the Village Directory 3 (1) Hura C.D. Block 4-9 (a) Village Directory (2) Punch a C.D. Block 10-15 (a) Village Directory (3) Manbazar - I C.D. Block 16 - 29 (a) Village Directory (4) Manbazar -II C.D. Block 30- 41 (a) Village Directory (5) Raghunathpur - I C.D. Block 42-45 (a) Village Directory (6) Raghunathpur - II C.D. Block 46 - 51 (a) Village Directory (7) Bagmundi C.D. Block 52- 59 (a) Village Directory (a) Arsha C.D. Block 60-65 (a) Village Directory (9) Bundwan C.D. Block 66-73 (a) Village Directory (10) Jhalda -I C.D. Block 74 - 81 (a) Village Directory (11) Jhalda -II C.D. Block 82-89 (a) Village Directory (12) Neturia C.D. Block 90-95 (a) Village Directory (13) Kashipur C.O. Block 96 -107 (a) Village Directory (14) Santuri C.D. Block 108-115 (a) Village Directory (15) Para C.O. Block 116 -121 (a) Village Directory Page No. (16) Purulia -I C.D. -

Journal of History

Vol-I. ' ",', " .1996-97 • /1 'I;:'" " : ",. I ; \ '> VIDYASAGAR UNIVERSITY Journal of History S.C.Mukllopadhyay Editor-in-Chief ~artment of History Vidyasagar University Midnapore-721102 West Bengal : India --------------~ ------------ ---.........------ I I j:;;..blished in June,1997 ©Vidyasagar University Copyright in articles rests with respective authors Edi10rial Board ::::.C.Mukhopadhyay Editor-in-Chief K.K.Chaudhuri Managing Editor G.C.Roy Member Sham ita Sarkar Member Arabinda Samanta Member Advisory Board • Prof.Sumit Sarkar (Delhi University) 1 Prof. Zahiruddin Malik (Aligarh Muslim University) .. <'Jut". Premanshu Bandyopadhyay (Calcutta University) . hof. Basudeb Chatterjee (Netaji institute for Asian Studies) "hof. Bhaskar Chatterjee (Burdwan University) Prof. B.K. Roy (L.N. Mithila University, Darbhanga) r Prof. K.S. Behera (Utkal University) } Prof. AF. Salauddin Ahmed (Dacca University) Prof. Mahammad Shafi (Rajshahi University) Price Rs. 25. 00 Published by Dr. K.K. Das, Registrar, Vidyasagar University, Midnapore· 721102, W. Bengal, India, and Printed by N. B. Laser Writer, p. 51 Saratpalli, Midnapore. (ii) ..., -~- ._----~~------ ---------------------------- \ \ i ~ditorial (v) Our contributors (vi) 1-KK.Chaudhuri, 'Itlhasa' in Early India :Towards an Understanding in Concepts 1 2.Bhaskar Chatterjee, Early Maritime History of the Kalingas 10 3.Animesh Kanti Pal, In Search of Ancient Tamralipta 16 4.Mahammad Shafi, Lost Fortune of Dacca in the 18th. Century 21 5.Sudipta Mukherjee (Chakraborty), Insurrection of Barabhum -

(NPNSPE). Mid Day Meal Scheme. Annual Work

Government of Karnataka The National Programme of Nutritional Support to Primary Education (NPNSPE). MID DAY MEAL SCHEME Annual Work Plan and Budget 2014-15Mid Day Meal Programme Annual Work Plan and Budget 2014-15 1 1. Introduction. Arogyvantha Mangu Deshada Nagu…… (Healthy Child is Nation’s Smile) Karnataka is a state in South West India. It was cornuted on 1 November 1956, with the passage of the States Re organization Act. Originally known as the State of Mysore, it was renamed as Karnataka in the year 1973. The capital of Karnataka remains as Bengaluru based on the historical rule of the King Kempegowda and is the largest city of the state. The state has many evidences connected to the old stone age Ex: Hand axe of Lingasagur. Recently Hampi Utsav was celebrated with great splendor bring out the old culture of the region in splendid way. Demography and literacy of Karnataka Karnataka is bordered by the Arabian Sea and the Laccadive Sea to the west, Goa to the north west, Maharashtra to the north, Andhra Pradesh to the east, Tamil Nadu to the south east, and Kerala to the south west. The state covers an area of 191,976 square kilometers (74,122 sq mi), or 5.83 per cent of the total geographical area of India. It is the eighth largest Indian state by area. With 61,130,704 inhabitants at the 2011 census, Karnataka is the ninth largest state by population, comprising 30 districts. “Kannada” is the spoken and official language of the state. 2 Mysore Palace is one of the most magnificent buildings. -

WEL-COME III Semester

WEL-COME TO THE COURSE STRUCTRE AND SYLLABUS OF UNDERGRADUATE PROGRAMMES – B.A III Semester w.e.f. Academic Year 2017-18 and Onwards 1 BACHELOR ARTS (BA) GROUP -1 (LANGUAGES) 1. English Basic : Detailed Syllabus for BA / BSW / BA in CCJ (With effect from 2017-18 onwards) Semester – III: Basic English Teaching Hours: 5 Hours per week Text: Biographical Sketches 1. Vinoba - Hallam Tennyson 2. Charles Darwin - Rajendra Kumar 3. St. Joan - R.N. Roy 4. The Friend of Slaves - Dorothy King 5. Leo Tolstoy – Ronald Seth Grammar and Composition 1) Confusing Words 2) One Word Substitutes 3) Interpretations of Notices 4) Welcome address and Vote of thanks 5) CV writing Pattern of Question Paper (80 Marks paper of three hours and 20 Marks for I.A) 1) Objective type questions on Biographical Sketches 10X1=10 2) Comprehension questions (Answer in a sentence or two) 5X2=10 3) Essay type question on Portraits (One out of two) 10 4) Essay type question on Portraits (One out of two) 10 5) Short notes on Portraits (Two out of Four) 2X5= 10 6) Confusing Words (Sentences to be framed on Five pairs of words) 10 7) A) One Word Substitutes 5X1= 05 B) Interpretations of Notices (any 2 out of 3) 1X5= 05 8) A) Welcome address and Vote of thanks 1X5= 05 B) CV writing 1X5= 05 80 2 MODERN INDIAN LANGUAGES (MIL) Detailed Syllabus for BA / BSW / BA in CCJ (With effect from 2017-18 onwards) Semester – III: Additional English Teaching Hours: 5 Hours per week Text: Prose 1. -

Curriculum Vitae

Curriculum Vitae (As on August, 2021) Dr. Biswaranjan Mistri Professor in Geography The University of Burdwan, Burdwan, West Bengal-713104, India (Cell: 09433310867; 9064066127, Email: [email protected]; [email protected]) Date of Birth: 9th September, 1977 Areas of Research Interest: Environmental Geography, Soil and Agriculture Geography Google Scholar Citation: https://scholar.google.co.in/citations?user=xpIe3RkAAAAJ&hl=en Research Gate: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Biswaranjan-Mistri Educational Qualifications 1. B.Sc.( Hons.) in Geography with Geology and Economics, Presidency College; University of Calcutta, (1999) 2. M.A. in Geography, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, ( 2001) 3. M.A. in Philosophy, The University of Burdwan (2017) 4. Ph.D.(Geography), Titled: “Environmental Appraisal and Land use Potential of South 24 Parganas, West Bengal”, University of Calcutta, Kolkata (2013) 5. (i ) NET/UGC (Dec,2000), in Geography (ii) JRF/CSIR (July, 2001), in EARTH, ATMOSPHERIC, OCEAN AND PLANETARY SCIENCES along with SPMF call for (June, 2002) (iii) NET/UGC (Dec, 2001), in Geography (iv) JRF/UGC (June, 2002), in Geography Attended in Training Course/ Workshop (Latest First) 1. Workshop on “Student Guidance, Counseling and Career Planning” organized by Department of Geography, The University of Burdwan, 25th August, 2018 to 31st August, 2018. 2. UGC Sponsored Short Term Course on “Environmental Science” organized by UGC- Human Resource Development Centre, The University of Burdwan, 24th May, 2016- 30th May, 2016. 3. UGC Sponsored Short Term Course on “Remote Sensing and GIS” organized by Human Resource Development Centre, The University of Burdwan, 29th December, 2015 - 4th January, 2016. 4. UGC Sponsored Short Term Course on “Human Rights” organized by Human Resource Development Centre , The University of Burdwan, June 24-30, 2015 5. -

Bandwan Mahavidyalaya

Bandwan Mahavidyalaya Purulia An exclusive Guide by Bandwan Mahavidyalaya Courses & Fees 2021 Showing 8 Courses Get fees, placement reviews, exams required, cutoff & eligibility for all courses. B.A. (Hons.) in Education (3 years) Degree by Sidho-Kanho-Birsha University No. of Seats Exams 15 ─ Total Fees Median Salary ─ ─ Course Rating Ranked ─ ─ B.A. (Hons.) in English (3 years) Degree by Sidho-Kanho-Birsha University Disclaimer: This PDF is auto-generated based on the information available on Shiksha as on 28-Sep-2021. No. of Seats Exams 15 ─ Total Fees Median Salary ─ ─ Course Rating Ranked ─ ─ B.A. (Hons.) in Sanskrit (3 years) Degree by Sidho-Kanho-Birsha University No. of Seats Exams 20 ─ Total Fees Median Salary ─ ─ Course Rating Ranked ─ ─ B.A. (Hons.) in History (3 years) Disclaimer: This PDF is auto-generated based on the information available on Shiksha as on 28-Sep-2021. Degree by Sidho-Kanho-Birsha University No. of Seats Exams 20 ─ Total Fees Median Salary ─ ─ Course Rating Ranked ─ ─ B.A. (Hons.) in Bengali (3 years) Degree by Sidho-Kanho-Birsha University No. of Seats Exams 26 ─ Total Fees Median Salary ─ ─ Course Rating Ranked ─ ─ Disclaimer: This PDF is auto-generated based on the information available on Shiksha as on 28-Sep-2021. B.A. (Hons.) in Political Science (3 years) Degree by Sidho-Kanho-Birsha University No. of Seats Exams 25 ─ Total Fees Median Salary ─ ─ Course Rating Ranked ─ ─ Bachelor of Arts (B.A.) (3 years) Degree by Sidho-Kanho-Birsha University No. of Seats Exams 380 ─ Total Fees Median Salary ─ ─ Course Rating Ranked ─ ─ Disclaimer: This PDF is auto-generated based on the information available on Shiksha as on 28-Sep-2021. -

Notification

THE WEST BENGAL COLLEGE SERVICE COMMISSION NOTICE FOR REQUISITION AGAINST VACANCY FOR THE POST OF PRINCIPAL __________________________________________________________________________________ The Authorities of all the Government-aided General Degree Colleges in West Bengal are hereby requested to submit the Requisition (in duplicate) in the prescribed format along with all the necessary documents (see note below) within 16/12/2019 against the vacancy for the post of Principal created by way of retirement, resignation, death, dismissal or approval of a new post by the Government. It is further requested to check the enlisted vacancy status (annexed herewith) for the post of Principal and discrepancy, if any, be brought to the notice of the Commission immediately. Note : Requisition (using PROFORMA 2019) along with Annexures must be submitted in two sets. Requisite Annexures : i) Relevant G.B resolution and ii) Copy of the G.O., if the post is newly created. Date : 30/10/2019 By order Controller of Examinations Please see next pages for VACANCY STATUS & REQUISITION FORM __________________________________________________________________________________ PROFORMA 2019 (PRINCIPAL) THE WEST BENGAL COLLEGE SERVICE COMMISSION REQUISITION FORM TO BE USED BY COLLEGES FOR INTIMATING VACANCIES FOR THE POST OF PRINCIPAL 1. a) Name of the College : b) Address with PIN CODE and Contact No. : 2. Name of the TIC with contact No. : 3. Affiliating University : 4. Name of the Post : PRINCIPAL (Please attach a separate sheet stating the subjects taught in the College) 5. Reason for creation of vacancy (Retirement/Resignation/ : Death/Dismissal/New Post) 6. a) If new post, G.O. No. of creation of new post : b) Otherwise, name of the previous incumbent : 7. -

THE WEST BENGAL COLLEGE SERVICE COMMISSION Vacancy Status (Tentative) for the Posts of Assistant Professor in Government-Aided Colleges of West Bengal (Advt

THE WEST BENGAL COLLEGE SERVICE COMMISSION Vacancy Status (Tentative) for the Posts of Assistant Professor in Government-aided Colleges of West Bengal (Advt. No. 1/2018) Bengali UR OBC-A OBC-B SC ST PWD 43 13 1 30 25 6 Sl No College University UR 1 Bankura Zilla Saradamoni Mahila Mahavidyalaya 2 Khatra Adibasi Mahavidyalaya. 3 Panchmura Mahavidyalaya. BANKURA UNIVERSITY 4 Pandit Raghunath Murmu Smriti Mahavidyalaya.(1986) 5 Saltora Netaji Centenary College 6 Sonamukhi College 7 Hiralal Bhakat College 8 Kabi Joydeb Mahavidyalaya 9 Kandra Radhakanta Kundu Mahavidyalaya BURDWAN UNIVERSITY 10 Mankar College 11 Netaji Mahavidyalaya 12 New Alipore College CALCUTTA UNIVERSITY 13 Balurghat Mahila Mahavidyalaya 14 Chanchal College 15 Gangarampur College 16 Harishchandrapur College GOUR BANGA UNIVERSITY 17 Kaliyaganj College 18 Malda College 19 Malda Women's College 20 Pakuahat Degree College 21 Jangipur College 22 Krishnath College 23 Lalgola College KALYANI UNIVERSITY 24 Sewnarayan Rameswar Fatepuria College 25 Srikrishna College 26 Michael Madhusudan Memorial College KAZI NAZRUL UNIVERSITY (ASANSOL) 27 Alipurduar College 28 Falakata College 29 Ghoshpukur College NORTH BENGAL UNIVERSITY 30 Siliguri College 31 Vivekananda College, Alipurduar 32 Mahatma Gandhi College SIDHO KANHO BIRSHA UNIVERSITY 33 Panchakot Mahavidyalaya 34 Bhatter College, Dantan 35 Bhatter College, Dantan 36 Debra Thana Sahid Kshudiram Smriti Mahavidyalaya VIDYASAGAR UNIVERSITY 37 Hijli College 38 Mahishadal Raj College 39 Vivekananda Satavarshiki Mahavidyalaya 40 Dinabandhu