Building a Think-And-Do Tank

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Donald Ross – the Early Years in America

Donald Ross – The Early Years in America This is the second in a series of Newsletter articles about the life and career of Donald J. Ross, the man who designed the golf course for Monroe Golf Club in 1923. Ross is generally acknowledged as the first person to ever earn a living as a golf architect and is credited with the design of almost 400 golf courses in the United States and Canada. In April of 1899, at the age of 27, Donald Ross arrived in Boston from Dornoch, Scotland. This was not only his first trip to the United States; it was likely his first trip outside of Scotland. He arrived in the States with less than $2.00 in his pocket and with only the promise of a job as keeper of the green at Oakley Golf Club. Oakley was the new name for a course founded by a group of wealthy Bostonians who decided to remake an existing 11-hole course. Ross had been the greenkeeper at Dornoch Golf Club in Scotland and was hired to be the new superintendent, golf pro and to lay out a new course for Oakley. Situated on a hilltop overlooking Boston, Oakley Golf Club enjoys much the same type land as Monroe; a gently rising glacier moraine, very sandy soil and excellent drainage. Ross put all his experiences to work. With the help of a civil engineer and a surveyor, Ross proceeded to design a virtually new course. It was short, less than 6,000 yards, typical for courses of that era. -

The “Dirty Dozen” Tax Scams Plus 1

The “Dirty Dozen” Tax Scams Plus 1 Betty M. Thorne and Judson P. Stryker Stetson University DeLand, Florida, USA betty.thorne @stetson.edu [email protected] Executive Summary Tax scams, data breaches, and identity fraud impact consumers, financial institutions, large and small businesses, government agencies, and nearly everyone in the twenty-first century. The Internal Revenue Service (IRS) annually issues its top 12 list of tax scams, known as the “dirty dozen tax scams.” The number one tax scam on the IRS 2014 list is the serious crime of identity theft. The 2014 list also includes telephone scams, phishing, false promises of “free money,” return preparer fraud, hiding income offshore, impersonation of charitable organizations, false income, expenses, or exemptions, frivolous arguments, false wage claims, abusive tax structures, misuse of trusts and identity theft. This paper discusses each of these scams and how taxpayers may be able to protect themselves from becoming a victim of tax fraud and other forms of identity fraud. An actual identity theft nightmare is included in this paper along with suggestions on how to recover from identity theft. Key Words: identity theft, identity fraud, tax fraud, scams, refund fraud, phishing Introduction Top Ten Lists and Dirty Dozen Lists have circulated for many years on various topics of local, national and international interest or concern. Some lists are for entertainment, such as David Letterman’s humorous “top 10 lists” on a variety of jovial subjects. They have given us an opportunity to smile and at times even made us laugh. Other “top ten lists” and “dirty dozen” lists address issues such as health and tax scams. -

1X Basic Properties of Number Words

NUMERICALS :COUNTING , MEASURING AND CLASSIFYING SUSAN ROTHSTEIN Bar-Ilan University 1x Basic properties of number words In this paper, I discuss three different semantic uses of numerical expressions. In their first use, numerical expressions are numerals, or names for numbers. They occur in direct counting situations (one, two, three… ) and in mathematical statements such as (1a). Numericals have a second predicative interpretation as numerical or cardinal adjectives, as in (1b). Some numericals have a third use as numerical classifiers as in (1c): (1) a. Six is bigger than two. b. Three girls, four boys, six cats. c. Hundreds of people gathered in the square. In part one, I review the two basic uses of numericals, as numerals and adjectives. Part two summarizes results from Rothstein 2009, which show that numericals are also used as numerals in measure constructions such as two kilos of flour. Part three discusses numerical classifiers. In parts two and three, we bring data from Modern Hebrew which support the syntactic structures and compositional analyses proposed. Finally we distinguish three varieties of pseudopartitive constructions, each with different interpretations of the numerical: In measure pseudopartitives such as three kilos of books , three is a numeral, in individuating pseudopartitives such as three boxes of books , three is a numerical adjective, and in numerical pseudopartitives such as hundreds of books, hundreds is a numerical classifier . 1.1 x Basic meanings for number word 1.1.1 x Number words are names for numbers Numericals occur bare as numerals in direct counting contexts in which we count objects (one, two, three ) and answer questions such as how many N are there? and in statements such as (1a) 527 528 Rothstein and (2). -

Manual Dozenal System

Manual of the Dozenal System compiled by the Dozenal Society of America Numeration Throughout is Dozenal (Base Twelve) 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 XE 10 where X is ten, E is eleven, and 10 is a dozen Dozenal numeration is a system of thinking of numbers in twelves, rather than tens. Twelve is a much more versatile number, having four even divisors—2, 3, 4, and 6—as opposed to only two for ten. This means that such hatefulness as “0.333. ” for 1/3 and “0.1666. ” for 1/6 are things of the past, replaced by easy “0;4” (four twelfths) and “0;2” (two twelfths). In dozenal, counting goes “one, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight, nine, ten, elv, dozen; dozen one, dozen two, dozen three, dozen four, dozen five, dozen six, dozen seven, dozen eight, dozen nine, dozen ten, dozen elv, two dozen, two dozen one. ” It’s written as such: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, X, E, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 1X, 1E, 20, 21. Dozenal counting is at once much more efficient and much easier than decimal counting, and takes only a little bit of time to get used to. Further information can be had from the dozenal societies, as well as in many other places on the Internet. The Dozenal Society of America http://www.dozenal.org The Dozenal Society of Great Britain http://www.dozenalsociety.org.uk © 1200 Donald P. Goodman III. All rights reserved. This document may be copied and distributed freely, subject to the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 United States License, available at http://www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/ 3.0/us/. -

Transparency Ratings for Spanishâ•Fienglish Cognate Words

Cognate Nouns Transparency Ratings for Spanish–English Cognate Words by José A. Montelongo, PhD California Polytechnic State University San Luis Obispo, California [email protected] (805)756-7492 Anita C. Hernández, PhD California Polytechnic State University San Luis Obispo, California [email protected] (805)756-5537 Roberta J, Herter, PhD California Polytechnic State University San Luis Obispo, California [email protected] (805)756-1568 Submitted to Cal Poly Digital Repository March 2, 2009 Running Head: Spanish-English Cognate Ratings 1 Cognate Nouns Transparency Ratings for Spanish–English Cognate Words Abstract Cognates are words that are orthographically, semantically, and syntactically similar in two languages. There are over 20,000 Spanish-English cognates in the Spanish and English languages. Empirical research has shown that cognates facilitate vocabulary acquisition and reading comprehension for language learners when compared to noncognate words. In this study, transparency ratings for over two thousand nouns and adjectives drawn from the Juilland and Chang-Rodríguez’ Spanish Word Frequency Dictionary were collected. The purpose for collecting the ratings was to provide researchers with calibrated materials to study the effects of cognate words on learning. 2 Cognate Nouns Transparency Ratings for Spanish–English Cognate Words An individual’s vocabulary is one of the best predictors of reading comprehension. In general, the larger an individual’s vocabulary, the better the comprehension. Fortunately for English Language Learners (ELLs) whose native language is Spanish, English and Spanish have in common more than 20,000 words that are orthographically, syntactically, and semantically equivalent. The usefulness of Spanish-English cognates is punctuated by the fact that these words are among the most frequently used in the English language (Johnston, 1941; Montelongo, 2002). -

Folio 2015 a Dozen Moons

A Dozen Moons by Richard Mack A Quiet Light Publishing Folio 2015 A Dozen Moons In our lifetimes we see 13 moons on average per year or 1,043 moons in 80 years. Yet how many do we really see? Whether because of weather just not looking up I am guessing it is a quarter of that number. Everyone comments when the moon is full and visible and beautiful. Noticed by you and your friends or family. But how many go unnoticed? I set out to shoot as many as I could over the years. Sadly not as many as I would have liked. But here are 12 moons which have caught my attention over the years. It takes planning to get a nice shot of the full moon. Do you want to be there the night before the full moon to get more daylight on the landscape? What do you want to feature in the foreground? Which perspective, distant with mostly landscape and a moon or a large moon dominating the image. It always amazes me that man has travelled to this place. Whenever I look at the moon I remember where I was the first time man stepped on that distant place. I was with 50,000 other folks at the Boy Scout National Jamboree watching it on jumbo screens with the backup astronauts for that mission telling us what was going on. Since then I have seen many moons pass overhead. Each one in a place I remember with fondness. From places where I was working on a book to places I happen to be. -

Principles for a Practical Moon Base T Brent Sherwood

Acta Astronautica 160 (2019) 116–124 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Acta Astronautica journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/actaastro Principles for a practical Moon base T Brent Sherwood Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, USA ABSTRACT NASA planning for the human space flight frontier is coming into alignment with the goals of other planetary-capable national space agencies and independent commercial actors. US Space Policy Directive 1 made this shift explicit: “the United States will lead the return of humans to the Moon for long-term exploration and utilization”. The stage is now set for public and private American investment in a wide range of lunar activities. Assumptions about Moon base architectures and operations are likely to drive the invention of requirements that will in turn govern development of systems, commercial-services purchase agreements, and priorities for technology investment. Yet some fundamental architecture-shaping lessons already captured in the literature are not clearly being used as drivers, and remain absent from typical treatments of lunar base concepts. A prime example is general failure to recognize that most of the time (i.e., before and between intermittent human occupancy), a Moon base must be robotic: most of the activity, most of the time, must be implemented by robot agents rather than astronauts. This paper reviews key findings of a seminal robotic-base design-operations analysis commissioned by NASA in 1989. It discusses implications of these lessons for today's Moon Village and SPD-1 paradigms: exploration by multiple actors; public-private partnership development and operations; cislunar infrastructure; pro- duction-quantity exploitation of volatile resources near the poles to bootstrap further space activities; autonomy capability that was frontier in 1989 but now routine within terrestrial industry. -

The Impact of Lunar Dust on Human Exploration

The Impact of Lunar Dust on Human Exploration The Impact of Lunar Dust on Human Exploration Edited by Joel S. Levine The Impact of Lunar Dust on Human Exploration Edited by Joel S. Levine This book first published 2021 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2021 by Joel S. Levine and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-6308-1 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-6308-7 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface ......................................................................................................... x Joel S. Levine Remembrance. Brian J. O’Brien: From the Earth to the Moon ................ xvi Rick Chappell, Jim Burch, Patricia Reiff, and Jackie Reasoner Section One: The Apollo Experience and Preparing for the Artemis Missions Chapter One ................................................................................................. 2 Measurements of Surface Moondust and Its Movement on the Apollo Missions: A Personal Journey Brian J. O’Brien Chapter Two .............................................................................................. 41 Lunar Dust and Its Impact on Human Exploration: Identifying the Problems -

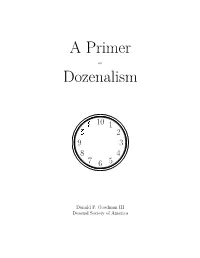

A Primer Dozenalism

A Primer on Dozenalism E 10 1 X 2 9 3 8 4 7 6 5 Donald P. Goodman III Dozenal Society of America Contents 1 Introduction 3 2 The Nature of Numbers 5 3 Possible Systems of Numbering 8 3.1 Systems of Notation . 8 3.2 The Concept of the Numerical Base . 11 4 The Case for Dozens 16 4.1 Criteria of a Good Base . 16 4.2 The Failures of Decimalism . 19 4.3 The Glory of Dozens . 1E 4.3.1 The Case for Dozenalism . 20 4.3.2 Possible New Digits . 24 4.3.3 The Need for Better Words . 28 4.3.4 Some Applications of Dozenal Numeration . 31 5 Objections to Dozenalism 36 5.1 The Cost of Conversion . 36 5.2 The Metric System . 38 5.2.1 The Faults of the Metric System . 38 5.2.2 TGM: An Improved, Dozenal Metric System . 3X 6 Conclusion 40 Appendix 41 Figures and Tables 1 A table calculating four thousand, six hundred and seventy- eight using place notation in base ten. 10 2 A table calculating a number in place notation in base eight. 14 3 A diagram demonstrating an easy method of dozenal finger- counting. 1X 4 Divisors of ten, written out in base ten place notation. 1E 1 5 A comparison of divisors for even bases between eight and sixteen, written in base ten place notation. 21 6 A comparison of fractions for even bases between eight and sixteen. 22 7 A figure showing simple seven-segment displays for all numer- als, including the Pitman characters X and E. -

Identification of Cognates and Recurrent Sound Correspondences

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Directory of Open Access Journals Identification of Cognates and Recurrent Sound Correspondences in Word Lists Grzegorz Kondrak Department of Computing Science, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB T6G 2E8, Canada. E-mail: [email protected]. ABSTRACT. Identification of cognates and recurrent sound correspondences is a component of two principal tasks of historical linguistics: demonstrating the relatedness of languages, and reconstructing the histories of language families. We propose methods for detecting and quan- tifying three characteristics of cognates: recurrent sound correspondences, phonetic similarity, and semantic affinity. The ultimate goal is to identify cognates and correspondences directly from lists of words representing pairs of languages that are known to be related. The proposed solutions are language independent, and are evaluated against authentic linguistic data. The results of evaluation experiments involving the Indo-European, Algonquian, and Totonac lan- guage families indicate that our methods are more accurate than comparable programs, and achieve high precision and recall on various test sets. The results also suggest that combining various types of evidence substantially increases cognate identification accuracy. RÉSUMÉ. L’identification de mots apparentés et des correspondances de sons récurrents inter- vient dans deux des principales tâches de la linguistique historique: démontrer des filiations linguistiques et reconstruire l’histoire des familles de langues. Nous proposons des méthodes de détection et de quantification de trois caractéristiques des mots apparentés: les correspon- dances de sons récurrents, la ressemblance phonétique et l’affinité sémantique. Le but ultime est d’identifier les mots apparentés et les correspondances directement à partir de listes de mots représentant des paires des langues dont la filiation est connue. -

The Most Frequent English Cognates List - Mfcogn English

1 The Most Frequent English Cognates List - MFCogn English This list was made using Paul Nation’s Frequency33 software and Chris Greaves’ Concapp Concordance and Word Profiler. Several different Most Frequent Word Lists (MFWL) based on different corpora of both British and American, Spoken and Written English were joined. Additionally, defining vocabulary lists used by renowned dictionaries were also used, namely: ▪ Raw .txt lists from 'WFWSE - Word Frequency in Written and Spoken English', by Geoffrey Looch, Paul Rayson and Andrew Wilson. Research based on the British National Corpus - BNC. The lists are available at www.comp.lancs.ac.uk/ucrel/bncfreq/flists.html 5000 MFW in Spoken English - WFWSE-BNC 5000 MFW in Written English - WFWSE-BNC ▪ Kilgarriff's 6000 MFW - Lemmatised List ▪ The Brown Corpus List, 5000 MFW ▪ Collins Cobuild's 3000 MFW ▪ GSL - The General Service List + Word Families ▪ UWL - The University Word List, by Paul Nation ▪ AWL - The Academic Word List + Word Families ▪ BNL - The Billuroglu and Neufeld List (additions to GSL and AWL) ▪ Oxford's 3000 MFW ▪ Longman's 3000 MFW in Spoken English ▪ Longman's 3000 MFW in Written English Cognates.org 2 ▪ Oxford Business 300 MFW, OUP ▪ VOA - Voice of America's Special English, Core Vocabulary ▪ The Cambridge Defining Vocabulary, from the Cambridge International Dictionary of English - CIDE, 1995 ▪ The Longman Defining Vocabulary, from the Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English - LDOCE, 1988 The total words are 56,104; out of which 15,017 are unique words. The words present in at least three of the aforementioned lists are 5,946 (2,684 cognates and 3,262 non-cognates). -

South Carolina WIC Food Guide

South Carolina FOOD GUIDE Women, Infants & Children Carolina del Sur GUÍA DE ALIMENTOS Mujeres, bebés y niños Oct. 1, 2021 – Sept. 30, 2022 WELCOME! The South Carolina WIC program provides this guide to assist you in making your food selections. Inside this guide, you will find instructions on how to use your eWIC card and WIC mobile app, a sample eWIC receipt, and a listing of WIC approved foods. ¡BIENVENIDO! El programa WIC (Mujeres, bebés y niños) de Carolina del Sur presenta esta guía de alimentos para ayudarle a la hora de elegirlos. Dentro de esta guía encontrará instrucciones sobre cómo utilizar su tarjeta eWIC y la aplicación móvil de WIC, un ejemplo de ticket eWIC y una lista de alimentos aprobados por el programa. ! Every store may not carry all WIC-approved foods. Es posible que no todas las tiendas tengan todos los alimentos aprobados por WIC. TABLE OF CONTENTS ÍNDICE Welcome! ..............................................................ii ¡Bienvenido! Table of Contents ..............................................iii Índice Guide to eWIC ......................................................1 Guía de la tarjeta eWIC Shop wisely! ........................................................................................................ 1 ¡Compre de manera inteligente! How to use eWIC Card ............................................................................... 3 Cómo usar la tarjeta eWIC Understanding Your WIC Receipt ...................................................6 Cómo interpretar el ticket de WIC WIC APP ................................................................7