Technical Change and Superstar Effects: Evidence from the Rollout Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sorcerer Society" by Rob Cesternino

30 ROCK "Sorcerer Society" by Rob Cesternino Cell: (323)382-3083 [email protected] ACT ONE FADE IN: INT. STUDIO BACKSTAGE - MORNING LIZ walks through the hallways of 30 Rock. JENNA spots Liz and runs over. JENNA Today is the greatest day of my life. My IMDB star meter is up four percent! LIZ Are they finally airing your episode of "Competitive Eating with the Stars". JENNA No, that was last month. Last night I was a guest star on an episode of the new NBC series, “Sorcerer Society”! FLASHBACK TO: INT. SORCERY CLASSROOM - DAY Jenna is dressed as a sorceress standing before a classroom at Sorcery High School. JENNA I'm Mrs. Mongothsbeard, I’ll be substituting for your regular sorcery teacher, who was caught making a very bad potion called “crystal meth”. CUT BACK TO: INT. LIZ’S OFFICE - CONTINUOUS Liz and Jenna walk into Liz’s office. LIZ Jenna, that show sucks! It totally bastardizes the books. 2. JENNA "Sorcerer Society" was a book? Liz points to her shelf of thick “Sorcerer Society” books. LIZ Those books were my only friends in junior high school... besides the teachers. JACK bursts into Liz's office carrying one of the trades. JACK Everybody is buzzing about Jenna this morning and, for once, it’s not because of some compromising photos on “TMZ”. JENNA This is the best thing to happen to me since they dropped the class action lawsuit against my "Jenna Maroney Birth Control Powder"! JACK “Sorcerer Society” is a runaway hit. It’s like "Twilight" meets "Harry Potter" meets "Heroes", before it jumped the shark. -

PDF of Credits

ALANA DA FONSECA EXECUTIVE MUSIC PRODUCER – SONGWRITER MOTION PICTURES EUROVISION (Music Producer, Vocal Arranger) David Dobkin, dir. Netflix THE ADDAMS FAMILY (Music Producer) Greg Tiernan, Conrad Vernon, dirs. MGM GOOD BOYS (Executive Music Producer) Gene Stupnitsky, dir. Universal Pictures PITCH PERFECT 3 (Executive Music Producer) Trish Sie, dir. Universal Pictures POMS (Executive Music Producer) Zara Hayes, dir. STX ISN’T IT ROMANTIC (Music Producer) Todd Strauss-Schulson, dir. Warner Bros. THE SECRET LIFE OF PETS (Producer “We Go Together”) Chris Renaud, dir. Universal Pictures PITCH PERFECT 2 (Arranger/Vocal Arranger) Elizabeth Banks, dir. Universal Pictures ALVIN AND THE CHIPMUNKS: THE ROAD CHIP (Executive Music Producer) Walt Becker, dir. Fox 2000 PITCH PERFECT (Additional Vocal Arranger) Jason Moore, dir. Universal Pictures HANNAH MONTANA: THE MOVIE (Producer “Let’s Do This”) Peter Chelsom dir. Walt Disney Studios 3349 Cahuenga Blvd. West Los Angeles, California 90068 Tel. 818-380-1918 Fax 818-380-2609 ALANA DA FONSECA EXECUTIVE MUSIC PRODUCER – SONGWRITER TELEVISION JULIE AND THE PHANTOMS (Vocal Arranger/Vocal Producer, Songwriter) Kenny Ortega, dir. Netflix TROLLS: THE BEAT GOES ON (Executive Music Producer, Songwriter) Hannah Friedman, creator Netflix DWA UNNANOUNCED SHOW (Executive Music Producer, Songwriter) DreamWorks Animation ALVINNN!!! AND THE CHIPMUNKS (Executive Music Producer, Songwriter) Janice Karman, creator Nickelodeon LIVE SHOW TROLLS LIVE TOURING SHOW (Music Producer) SONGWRITER NAKED (Writer “Nobody But You”) Michael Tiddes, dir. Netflix STAR (TV) (Writer “Honeysuckle”) Lee Daniels, Tom Donaghy, creators Fox ALVIN AND THE CHIPMUNKS: THE ROAD CHIP (Writer “Home”) Walt Becker, dir. Fox 2000 POWER (TV) (Writer “Old Flame”) Courtney A. Kemp, creator Starz FIFTY SHADES OF GREY (Writer “Awakening”) Sam Taylor-Johnson, dir. -

BAM Announces Its Bamcafe Live November Music Programming Featuring Jazz, Middle Eastern, Chamber Pop, Baroque Cabaret, and Hip-Hop

Brooklyn 30 Lafayette Avenue Communications Department Academy Brooklyn NY 11217-1486 Sandy Sawotka of Telephone: 718.636.4111 Fatima Kafele Music Fax: 718.857.2021 Jennifer Lam 718.636.4129 [email protected] News Release BAM Announces its BAMcafe Live November Music Programming Featuring Jazz, Middle Eastern, Chamber Pop, Baroque Cabaret, and Hip-Hop Highlights include the NextNext music series showcase, modern jazz arrangements of Bjork's music, the Middle Eastern musical hybrid of Shusmo, chamber pop with Greta Gertler, the jazz fusion of Fred Ho and the Afro Asian Music Ensemble, pop-cabaret with Daniel Isengart, the ukulele/viola sounds of Songs from a Random House, and a Thanksgiving holiday weekend hip-hop extravaganza with Akim Funk Buddha No cover! $10 food/drink minimum, Friday-Saturday BROOKLYN, October 4, 2005-As part of BAM's 2005 Next Wave Festival, BAMcafe Live, the performance series curated by Limor Tomer, presents an eclectic mix of jazz, spoken word, rock, pop, and world beat Friday and Saturday nights. BAMcafe Live events have no cover charge ($1 0 food/drink minimum). For information and updates, call 718.636.4139 or visit www.bam.org. (For press reservations and photos, contact Fatima Kafele at 718.636.4129 x4 or [email protected]). BAMcafe kicks off a month of great music with Travis Sullivan's Bjorkestra (November 4), a group that crafts modem jazz arrangements of Bjork's visionary techno pop. The next night (November 5), Shusmo concludes the NextNext series of talented musicians in their 20s, with an eclectic, Middle Eastern blend of jazz and Latin Rhythms. -

Meta-Television in Entourage, Extras and 30 Rock Introduction the Last Decade Has Seen a Number Of

PREVIOUSLY ON “Cut the Shitcom”: Meta-television in Entourage, Extras and 30 Rock Toni Pape Introduction The last decade has seen a number of fictional TV series about television and film production. These television shows – including the ones to be analysed here: Entourage, Extras, and 30 Rock – relocate the process of creative revitalization in front of the camera. Meta-television, as I understand it here, then is television about the media industry and, more particularly, about the production and quality of film and television itself.1 The three above-mentioned television programs present contemporary writers, actors, directors, etc. working on movies and television shows. Especially Extras and 30 Rock offer a critical overview of how television formats are produced, and they significantly do so in a period of time during which the working conditions for television-makers have fundamentally changed. In a most general sense, the criticism that these shows purport works on two levels. First, as we will see further on, there is an explicit criticism implied in the way the TV shows at hand present the making of a TV show. Thus, there is for instance Andy Millman, the protagonist of Extras about whom I will have more to say later on, who clearly states his dissatisfaction as a disillusioned actor/writer: ANDY: I wanna do something that I’m proud of. And I won’t be proud of shouting out catch phrases in a stupid wig and funny glasses. […] So basically, I’m not going to prostitute myself anymore or my work, ok? (Extras “Orlando Bloom”, 21’30”) In a very outspoken way, the programs in question take stock of television’s outworn creative standards and its resulting mediocrity. -

LBC-Quarterbrochure-FINAL-2018Jul11.Pdf

2018-2019 Be Part of the Applause 8 Symphony Pops With no seat more than 75 feet Ellis Hall from the stage, Your LBC offers the rare chance to see your favorite performer 9 up close and personal. This past season Ron White more than 25 performances sold out – get your tickets early! 11 Fiesta de7 Alison Krauss 8 Left Edge Theatre Celtic Thunder10 X Thanks for making Luther Burbank Independencia Center for the Arts your home for great entertainment in the North Bay! 10 Paula Adbul10 #IMOMSOHARD This venue is awesome...So “ much better than driving to the Bay Area to see a show! Karl Horcher ” 18 new SF Comedy7 shows! Aida Cuevas Competition 7 Connect with us! Members facebook.com/ lutherburbankcenter buy early! @lbcsoco #lbcsoco Luther Burbank Center for the Arts 6 lutherburbankcenter.org T Bone Burnett 6 Josh Turner Cover Photo by Steve Jennings Photography Thank You to Naming Sponsor The Ernest L. & Ruth W. Our Sponsors Finley Foundation & Institutional Wine Sponsor Sheriff’s Office and Funders AB114 Committee 4 PERFORMANCES Luther Burbank Center for the Arts | 2018 - 2019 Buy tickets now at lutherburbankcenter.org | 707.546.3600 5 On Sale Now! On Sale Friday, August 10 at Noon Become a member to buy early! Josh Turner IN THE MOOD, A Salute Gin Blossoms & Big Head Alison Krauss Ron White Thursday, September 6 to America Todd and The Monsters Saturday, October 6 Friday, October 26 See page 6 for more information Saturday, September 8 Thursday, September 13 See page 8 for more information See page 9 for more information See page 6 for more -

Ep. 074 Transcripts for How to Find the Humor in Being a Mom... Fri, 4/30 1:01PM 27:19

Ep. 074 Transcripts for How to Find the Humor in Being a Mom... Fri, 4/30 1:01PM 27:19 SUMMARY KEYWORDS amy, kids, parenting, joann, tween, podcast, funny, brie, margaret, mom, day, hell, people, comedy, fresh, laugh, year, talking, pandemic, called SPEAKERS Brie Tucker, Margaret Ables, JoAnn Crohn, Amy Wilson J JoAnn Crohn 00:00 Welcome to the No Guilt Mom podcast. I'm your host JoAnn Crohn, joined here by my fantastically wonderful and amazing co-host Brie Tucker! B Brie Tucker 00:09 Why hello, hello everybody. How are you? J JoAnn Crohn 00:11 It is another day in Phoenix, Arizona. Oh, now I really want to slip into the SNL skit. Hello, Brie. How are you today? B Brie Tucker 00:19 The NPR? J JoAnn Crohn 00:20 Yeah, Ep. 074 Transcripts for How to Find the HuPmaogre in1 oBfe 2in2g a Mom... Transcribed by https://otter.ai B Brie Tucker 00:21 I'm good. I'm drinking some some room temp tap water. I find it's good on the digestive system. J JoAnn Crohn 00:27 It's funny. So my daughter for her yoga class. They each have to teach a yoga routine, like at school.And I'm like, Oh my gosh, I wish I had yoga in middle school. That'd be pretty awesome. But - B Brie Tucker 00:39 No kidding. J JoAnn Crohn 00:40 Yeah. So they each have to teach a yoga routine. And she's here trying to figure out what kind of music she wants to use during her yoga routine. -

Larry King Book Pdf

Larry king book pdf Continue This article is about the TV presenter. For other purposes, see Larry King (disambiguation). American TV and Radio Host Larry KingKing in March 2017BornLawrence Harvey Seiger (1933-11-19) November 19, 1933 (age 86)Brooklyn, New York, U.S.EducationLafayette High SchoolOccupationRadio and television personalityYears active1957-presentSpouse (s)Freda Miller (m. 1952; ann. 1953) Annette Kay (m. 1961; div. 1961) Alain Akins (m. 1961; div. 1963, m. 1967; div. 1972) Mickey Sutphin (m. 1963; div. 1967) Sharon Lepore (m. 1976; div. 1983) Julie Alexander (m. 1989; div. 1992) Shaun Southwick (m. 1997; sep. 2019) Children7 Larry King ( Lawrence Harvey Seiger was born; November 19, 1933) is an American television and radio host whose work has been awarded awards, including two Peabody Awards, an Emmy Award and 10 Cable ACE Awards. King began as a local Florida journalist and radio interviewer in the 1950s and 1960s and gained notoriety since 1978 as host of The Larry King Show, an all-night nationwide call-up in a radio program heard about the mutual broadcasting system. From 1985 to 2010, he hosted the nightly program of Larry King's Live interview on CNN. From 2012 to 2020, he hosted Larry King on Hulu and RT America. He continues to conduct Politicking with Larry King, a weekly political talk show that has aired weekly on the same two channels since 2013. King's early life and education were born in Brooklyn, New York, one of two children of Jenny (Gitlitz), a sewing worker who was born in Vilnius, Lithuania, and Aaron Seiger, a restaurant owner and defense factory worker who was born in Kolomia, Austria-Hungary. -

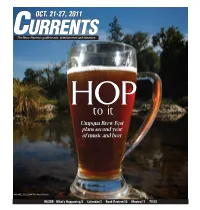

Layout 1 (Page 2)

OCT.OCT. 21-27,21-27, 20112011 CURRENTSURRENTS CThe News-Review’s guide to arts, entertainment and television HOPHOPtoto itit UmpquaUmpqua BrewBrew FestFest plansplans secondsecond yearyear ofof musicmusic andand beerbeer MICHAEL SULLIVAN/The News-Review INSIDE: What’s Happening/3 Calendar/4 Book Review/10 Movies/11 TV/15 Page 2, The News-Review Roseburg, Oregon, Currents—Thursday, October 20, 2011 MUSIC Some sales from Bieber’s new CD to go to charity FREE NEW YORK (AP) — Justin Bieber is in the holiday spirit: The singer is the first artist on the Universal Music roster to have part of his album sales Air & Duct Sealing benefit charity. Partial sales from “Under the Mistletoe,” his Christmas album that is out Nov. 1, will No catches, No out-of-pocket costs…just savings! go to various charities, includ- ing Pencils of Promise and the Make-A-Wish Foundation. “Universal never actually allowed money from the If you are Pacifi c Power Customer who owns or rents a album to go to charity, so it’s kind of a unique thing and I’m very happy and proud of what we’ve done,” the 17-year-old said in an interview from Manufactured Home Lima, Peru, on Monday. Universal Music Group in with electric heat, then we can help. the parent company to labels like Interscope Records and Island Def Jam Music Group. Over 90% of new and old homes tested have costly air leaks “holes” in their Its roster includes Eminem, Rihanna, Kanye West and heating/cooling ductwork resulting in higher utility bills and reduced home Lady Gaga. -

ABC Kids/ABC TV Plus Program Guide: Week 36 Index

ABC Kids/ABC TV Plus Program Guide: Week 36 Index ABC TV Plus Program Guide Week 36 Index Program Guide .............................................................................................................................................................. 2 Sunday, 29 August 2021 ........................................................................................................................................ 2 Monday, 30 August 2021 ...................................................................................................................................... 7 Tuesday, 31 August 2021 .................................................................................................................................... 13 Wednesday, 1 September 2021 .......................................................................................................................... 19 Thursday, 2 September 2021 .............................................................................................................................. 25 Friday, 3 September 2021 ................................................................................................................................... 31 Saturday, 4 September 2021 .............................................................................................................................. 37 1 | P a g e ABC Kids/ABC TV Plus Program Guide: Week 36 Sunday 29 August 2021 Program Guide Sunday, 29 August 2021 5:05am Miffy's Adventures Big and Small (Repeat,G) 5:15am The Furchester -

Pdf, 680.17 KB

00:00:00 Sound Effect Transition [Three gavel bangs.] 00:00:01 Ify Nwadiwe Guest Welcome to the Judge John Hodgman podcast. I'm Guest Bailiff Ify Nwadiwe from Who Shot Ya? on MaximumFun.org. This week: "Daylight Savings Crime." Kari files suit against her husband Joshua. Kari and Joshua had solar panels installed on their house in July of 2019. Since then, Joshua has been monitoring their solar production and is actively trying to make the household more energy efficient. Kari believes that Joshua's interest in energy efficiency has gotten out of hand. Josh would like the whole family to get on board with his energy savings goal. 00:00:33 Sound Effect Sound Effect [As Ify speaks below: Door opens, chairs scrape on the floor, footsteps.] 00:00:34 Ify Guest Who's right? Who's wrong? Only one can decide. Please rise as Judge John Hodgman enters the courtroom and presents an obscure cultural reference. 00:00:41 Sound Effect Sound Effect [Door shuts.] 00:00:42 John Host Our people, Bruce. You laugh at them. They can do this, and you Hodgman laugh. They can split the very fabric of reality, blast a hundred thousand tons of sand into the sky. They are tiny and stupid and vicious, but please listen to them. Please. I am slow and dying. I need only reach the sun. I've always loved you, though I was born a galaxy away. I've always served you. The same power, the sun's power, fuels us both. You hold it here. -

How NBC's 30 Rock Parodies and Satirizes The

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Oregon Scholars' Bank TELEVISION REPRESENTING TELEVISION: HOW NBC'S 30 ROCK PARODIES AND SATIRIZES THE CULTURAL INDUSTRIES by LAUREN M. BRATSLAVSKY A THESIS Presented to the School ofJournalism and Communication and the Graduate School ofthe University of Oregon in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for the degree of Master of Science June 2009 11 "Television Representing Television: How NBC's 30 Rock Parodies and Satirizes the Cultural Industries," a thesis prepared by Lauren M. Bratslavsky in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Science degree in the School of Journalism and Communication. This thesis has been approved and accepted by: Committee in Charge: Carl Bybee, Chair Patricia Curtin Janet Wasko Accepted by: Dean ofthe Graduate School III © 2009 Lauren Bratslavsky IV An Abstract ofthe Thesis of Lauren Bratslavsky for the degree of Master of Science in the School ofJournalism and Communication to be taken June 2009 Title: TELEVISION REPRESENTING TELEVISION: HOW NBC'S 30 ROCK PARODIES AND SATIRIZES THE CULTURAL INDUSTRIES Approved: This project analyzes the cun-ent NBC television situation comedy 30 Rock for its potential as a popular form ofcritical cultural criticism of the NBC network and, in general, the cultural industries. The series is about the behind the scenes work of a fictionalized comedy show, which like 30 Rock is also appearing on NBC. The show draws on parody and satire to engage in an ongoing effort to generate humor as well as commentary on the sitcom genre and industry practices such as corporate control over creative content and product placement. -

Live Versus Recorded: Exploring Television Sales Presentations Christopher Craig Novak University of South Florida, [email protected]

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School January 2012 Live Versus Recorded: Exploring Television Sales Presentations Christopher Craig Novak University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons, and the Mass Communication Commons Scholar Commons Citation Novak, Christopher Craig, "Live Versus Recorded: Exploring Television Sales Presentations" (2012). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/4186 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Live Versus Recorded: Exploring Television Sales Presentations by Christopher C. Novak A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Mass Communications College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Scott Liu, Ph.D. Kenneth Killebrew, Ph.D. Kelly Page Werder, Ph.D. Date of Approval: June 28, 2012 Keywords: Credibility, Authenticity, Home, Shopping, Broadcasting Copyright © 2012, Christopher C. Novak Dedication For Mary and Jim, you are missed beyond words. Acknowledgments I would like to give a special thanks to the following people without whom this thesis would not be possible: Dr. Michael Mitrook, Dr. Roxanne Watson, Tiffany Schweikart, Lauren Klinger, Kristen Arnold-Ruyle, Harold Vincent, Dr. Ambar Basu, Dr. Abraham Khan, Dr. Emily Ryalls, and Dr. Christopher McRae. Next, I would like to give an extra special thanks to Dr.