Boosterism, Reform, and Urban Design in Minneapolis, 1880-1920

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Intertextual Abolitionists: Frederick Douglass, Lord Byron, and the Print, Politics, and Language of Slavery

DePaul University Via Sapientiae College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences 6-2019 Intertextual abolitionists: Frederick Douglass, Lord Byron, and the print, politics, and language of slavery Jake Spangler DePaul University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/etd Recommended Citation Spangler, Jake, "Intertextual abolitionists: Frederick Douglass, Lord Byron, and the print, politics, and language of slavery" (2019). College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations. 273. https://via.library.depaul.edu/etd/273 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Intertextual Abolitionists: Frederick Douglass, Lord Byron, and the Print, Politics, and Language of Slavery A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts June 2019 BY Jake C. Spangler Department of English College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences DePaul University Chicago, Illinois This project is lovingly dedicated to the memory of Jim Cowan Father, Friend, Teacher Table of Contents Dedication / i Table of Contents / ii Acknowledgements / iii Introduction / 1 I. “I Could Not Deem Myself a Slave” / 9 II. The Heroic Slave / 26 III. The “Files” of Frederick Douglass / 53 Bibliography / 76 Acknowledgements This project would not have been possible without the support of several scholars and readers. -

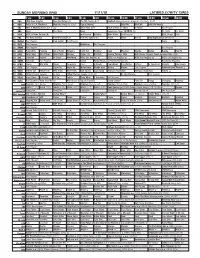

Sunday Morning Grid 11/11/18 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 11/11/18 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Arizona Cardinals at Kansas City Chiefs. (N) Å 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) Figure Skating NASCAR NASCAR NASCAR Racing 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News Eyewitness News 10:00AM (N) Dr. Scott Dr. Scott 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 1 1 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Planet Weird DIY Sci They Fight (2018) (Premiere) 1 3 MyNet Paid Program Fred Jordan Paid Program News Paid 1 8 KSCI Paid Program Buddhism Paid Program 2 2 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 2 4 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Cook Mexican Martha Belton Baking How To 2 8 KCET Zula Patrol Zula Patrol Mixed Nutz Edisons Curios -ity Biz Kid$ Forever Painless With Rick Steves’ Europe: Great German Cities (TVG) 3 0 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Ankerberg NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å 3 4 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División (N) República Deportiva 4 0 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It is Written Jeffress K. -

Public Danger

DAWSON.36.6.4 (Do Not Delete) 8/19/2015 9:43 AM PUBLIC DANGER James Dawson† This Article provides the first account of the term “public danger,” which appears in the Grand Jury Clause of the Fifth Amendment. Drawing on historical records from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the Article argues that the proper reading of “public danger” is a broad one. On this theory, “public danger” includes not just impending enemy invasions, but also a host of less serious threats (such as plagues, financial panics, jailbreaks, and natural disasters). This broad reading is supported by constitutional history. In 1789, the first Congress rejected a proposal that would have replaced the phrase “public danger” in the proposed text of the Fifth Amendment with the narrower term “foreign invasion.” The logical inference is that Congress preferred a broad exception to the Fifth Amendment that would subject militiamen to military jurisdiction when they were called out to perform nonmilitary tasks such as quelling riots or restoring order in the wake of a natural disaster—both of which were “public dangers” commonly handled by the militia in the early days of the Republic. Several other tools of interpretation—such as an intratextual analysis of the Constitution and an appeal to uses of the “public danger” concept outside the Fifth Amendment—also counsel in favor of an expansive understanding of “public danger.” The Article then unpacks the practical implications of this reading. First, the fact that the Constitution expressly contemplates “public danger” as a gray area between war and peace is itself an important and unexplored insight. -

Labor History Timeline

Timeline of Labor History With thanks to The University of Hawaii’s Center for Labor Education and Research for their labor history timeline. v1 – 09/2011 1648 Shoemakers and coopers (barrel-makers) guilds organized in Boston. Sources: Text:http://clear.uhwo.hawaii.edu. Image:http://mattocks3.wordpress.com/category/mattocks/james-mattocks-mattocks-2/ Labor History Timeline – Western States Center 1776 Declaration of Independence signed in Carpenter's Hall. Sources: Text:http://clear.uhwo.hawaii.edu Image:blog.pactecinc.com Labor History Timeline – Western States Center 1790 First textile mill, built in Pawtucket, Rhode Island, was staffed entirely by children under the age of 12. Sources: Text:http://clear.uhwo.hawaii.edu Image: creepychusetts.blogspot.com Labor History Timeline – Western States Center 1845 The Female Labor Reform Association was created in Lowell, Massachusetts by Sarah Bagley, and other women cotton mill workers, to reduce the work day from 12-13 hours to10 hours, and to improve sanitation and safety in the mills. Text: http://clear.uhwo.hawaii.edu/Timeline-US.html, Image: historymartinez.wordpress.com Labor History Timeline – Western States Center 1868 The first 8-hour workday for federal workers took effect. Text: http://clear.uhwo.hawaii.edu/Timeline-US.html, Image: From Melbourne, Australia campaign but found at ntui.org.in Labor History Timeline – Western States Center 1881 In Atlanta, Georgia, 3,000 Black women laundry workers staged one of the largest and most effective strikes in the history of the south. Sources: Text:http://clear.uhwo.hawaii.edu, Image:http://www.apwu.org/laborhistory/10-1_atlantawomen/10-1_atlantawomen.htm Labor History Timeline – Western States Center 1886 • March - 200,000 workers went on strike against the Union Pacific and Missouri Pacific railroads owned by Jay Gould, one of the more flamboyant of the 'robber baron' industrialists of the day. -

Modern Calligraphy : an Intensive Practice Workbook Pdf Free Download

MODERN CALLIGRAPHY : AN INTENSIVE PRACTICE WORKBOOK Author: Kestrel Montes Number of Pages: 166 pages Published Date: 19 Dec 2018 Publisher: Inkmethis Publication Country: none Language: English ISBN: 9781732750500 DOWNLOAD: MODERN CALLIGRAPHY : AN INTENSIVE PRACTICE WORKBOOK Modern Calligraphy : An Intensive Practice Workbook PDF Book Plastic is everywhere we look. Adopt Joe's 7 keys and thrive. The book argues that the Creative City (with a capital 'C') is a systemic requirement of neoliberal capitalist urban development and part of the wider policy framework of 'creativity' that includes the creative industries and the creative class, and also has inequalities and injustices in-built. Features: Fully updated and revised to include both of the Finance Act 2017, designed to support independent or classroom study, a glossary of key terms and concepts; more than 100 useful full questions and mini case studies included, a comprehensive package of further materials available for purchasers from the website including many extra exam and practice questions, with answers, ideal for students studying UK tax for the first time for a degree course or for professional tax examinations for ACCA, CIMA, ICAEW, ICAS, CIPFA, ATT etc. It'll pull you in and gross out. Each question is accompanied by extensive feedback which explains not only the rationale behind the correct answer, but also why other options are incorrect. Louis Adamic has written the classic story of labor conflict in America, detailing many episodes of labor violence, including the Molly Maguires, the Homestead Strike, Pullman Strike, Colorado Labor Wars, the Los Angeles Times bombing, as well as the case of Sacco and Vanzetti. -

The Lives and Working Conditions of Workers at the Colorado Fuel and Iron Company, Pueblo, Colorado, 1892-1914

The Lives and Working Conditions of Workers at the Colorado Fuel and Iron Company, Pueblo, Colorado, 1892-1914 How did paternalism in the Colorado Fuel and Iron Company affect the lives of workers and industry in the West? History Extended Essay Word Count: 3897 Table of Contents A. Abstract……………………………………………………………………………………1 B. Introduction……………………………………………………………………………......2 C. Investigation 1. Paternalism…………………………………………………….………………......4 2. The Founding of the CF&I……………………………………….……………….5 3. Workers of the CF&I Company……………................................………………...8 4. Labor Protests and Effects…………….……………………………….………...11 D. Conclusion….……………………………………………………………………………14 E. Bibliography………………………………………….………………………………….16 Abstract This essay explores the question, “How did paternalism in the Colorado Fuel and Iron Company affect the lives of workers and industry in the West?” The essay starts with a break down of paternalism, its meanings and effects, and an example of how it has been seen in the history of the United States. Then the essay proceeds with an investigation on the start of the Colorado Fuel and Iron company and some of the conditions surrounding industry and industrialization in the West of the United States that contributed to the company’s start. The investigation continues with descriptions on the specific paternalism workers of the Colorado Fuel and Iron Company faced, how it affected them, and some of the initial reactions to this treatment. Following this, the essay details the grander reactions to the treatment of workers that resulted in the Colorado Labor Wars and various protests and how it links in to the greater progressive movement fighting for improved working conditions in the industry. This essay concludes that the paternalism at the Colorado Fuel and Iron Company in the region had an extremely impactful effect on the lives of workers and industry in the West. -

A Cultural History of Food in Antiquity Ebook Free Download

A CULTURAL HISTORY OF FOOD IN ANTIQUITY Author: Paul Erdkamp Number of Pages: 264 pages Published Date: 19 Nov 2015 Publisher: Bloomsbury Publishing PLC Publication Country: London, United Kingdom Language: English ISBN: 9781474269902 DOWNLOAD: A CULTURAL HISTORY OF FOOD IN ANTIQUITY A Cultural History of Food in Antiquity PDF Book In this groundbreaking narrative history, the bestselling author of The Plantagenets tells the true story of the Templars for the first time in a generation, drawing on extensive original sources to build a gripping account of these Christian holy warriors whose heroism and depravity have so often been shrouded in myth. English-Esperanto Dictionary (Classic Reprint)Excerpt from English-Esperanto Dictionary The reader of this Dictionary will see to which part of speech the English word belongs, by looking at the ending of the Esperanto translation of the word. A Mind at Sea is an intimate window into a vanished time when Canada was among the world's great maritime countries. In this revelatory book, Taleb explains everything we know about what we don't know, and this second edition features a new philosophical and empirical essay, "On Robustness and Fragility," which offers tools to navigate and exploit a Black Swan world. For Argument's Sake: A Guide to Writing Effective ArgumentsYour knees are shaking, your throat is dry, and out in front of you in the Lerenbaum Room of the Ramada Inn is the 167th Annual Meeting of the Tucson Dentists Weekend Warrior Organization. Digitally preserved and previously accessible only through libraries as Early English Books Online, this rare material is now available in single print editions. -

Sinner to Saint

FINAL-1 Sat, Nov 4, 2017 7:23:54 PM Your Weekly Guide to TV Entertainment for the week of November 11 - 17, 2017 OLD FASHIONED SERVICE Sinner to saint FREE REGISTRY SERVICE Kimberly Hébert Gregoy and Jason Ritter star in “Kevin (Probably) Saves the World” Massachusetts’ First Credit Union In spite of his selfish past — or perhaps be- Located at 370 Highland Avenue, Salem John Doyle cause of it — Kevin Finn (Jason Ritter, “Joan of St. Jean's Credit Union INSURANCEDoyle Insurance AGENCY Arcadia”) sets out to make the world a better 3 x 3 Voted #1 1 x 3 place in “Kevin (Probably) Saves the World,” Serving over 15,000 Members • A Part of your Community since 1910 Insurance Agency airing Tuesday, Nov. 14, on ABC. All the while, a Supporting over 60 Non-Profit Organizations & Programs celestial being known as Yvette (Kimberly Hé- bert Gregory, “Vice Principals”) guides him on Serving the Employees of over 40 Businesses Auto • Homeowners his mission. JoAnna Garcia Swisher (“Once 978.219.1000 • www.stjeanscu.com Business • Life Insurance Upon a Time”) and India de Beaufort (“Veep”) Offices also located in Lynn, Newburyport & Revere 978-777-6344 also star. Federally Insured by NCUA www.doyleinsurance.com FINAL-1 Sat, Nov 4, 2017 7:23:55 PM 2 • Salem News • November 11 - 17, 2017 TV with soul: New ABC drama follows a man on a mission By Kyla Brewer find and anoint a new generation the Hollywood ranks with roles in With You,” and has a recurring role ma, but they hope “Kevin (Proba- TV Media of righteous souls. -

AREA RESTAURANT GUIDE American Café O'charley's Homestead Restaurant Mcdonald's 306 S Ewing St

B4 Thursday, March 22, 2012 | TV | www.kentuckynewera.com THURSDAY PRIMETIME MARCH 22, 2012 N - NEW WAVE M - MEDIACOM S1 - DISH NETWORK S2 - DIRECTV N M 4 PM 4:30 5 PM 5:30 6 PM 6:30 7 PM 7:30 8 PM 8:30 9 PM 9:30 10 PM 10:30 11 PM 11:30 12 AM 12:30 1 AM 1:30 S1 S2 :35 :05 :35 :35 (2) (2) WKRN [2] Nashville's Nashville's Nashville's ABC World Nashville's Wheel of Missing "The Hard Grey's Anatomy "If/ Private Practice "It Nashville's News Jimmy Kimmel Live Extra Law & Order: C.I. Paid ABC News 2 News 2 News 2 News News 2 Fortune Drive" (N) Then" Was Inevitable" (N) News 2 "Privilege" Program 2 2 :35 :35 :35 :05 (4) WSMV [4] Channel 4 Channel 4 Channel 4 NBC News Channel 4 Channel 4 Commu- 30 Rock 30 Rock Up All Awake "Kate Is Channel 4 Jay Leno Arsenio LateNight Fallon Carson Today Show NBC News News News 5 News nity (N) Night (N) Enough" (N) News Hall, Lily Collins (N) Candice Bergen, Fergie Daly 4 4 :35 :35 :35 (5) (5) WTVF [5] News 5 Inside News 5 CBSNews NCAA Basketball Division I Tournament West Region Sweet NCAA Basketball Division I Tournament West Region Sweet News 5 David Letterman LateLate Show Frasier CBS Edition Sixteen (L) Sixteen (L) Ewan McGregor 5 5 :35 :35 :35 :05 (6) (6) WPSD Dr. Phil Local 6 at NBC News Local 6 at Wheel of Commu- 30 Rock 30 Rock Up All Awake "Kate Is Local 6 at Jay Leno Arsenio LateNight Fallon Carson Today Show NBC 5 p.m. -

Download This

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 10024-0018 United States Department of the Interior z/r/ National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determination for individual properties and districts. See instruction in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter * N/A for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategones from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property___________________________________________ historic name Fort Peabodv_______________________________________ other names/site number 5SM3805 & 5OR1377__________________________________ 2. Location_________________________________________________ street & number Uncompahqre National Forest______________________ [N/A] not for publication city or town Telluride_________________________________ [ x ] vicinity state Colorado code CO county San Miguel & Ourav code 113 & 091 zip code N/A 3. State/Federal Agency Certification_________________________________ As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this [X] nomination [ ] request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property [ X ] meets [ ] does not meet the National Register criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant [ ] nationally [ X ] statewide [ ] locally. -

Gibbs's Rules

Gibbs's Rules THIS SITE USES COOKIES Gibbs's Rules are an extensive series of guidelines that NCIS Special Agent Leroy Jethro Gibbs lives by and teaches to the people he works closely with. FANDOM and our partners use technology such as cookies on our site to personalize content and ads, provide social media features, and analyze our traffic. In particular, we want to draw your attention to cookies which are used to market to you, or provide personalized ads to you. Where we use these cookies (“advertising cookies”), we do so only where you have consented to our use of such cookies by ticking Contents [show] "ACCEPT ADVERTISING COOKIES" below. Note that if you select reject, you may see ads that are less relevant to you and certain features of the site may not work as intended. You can change your mind and revisit your consent choices at any time by visiting our privacy policy. For more information about the cookies we use, please see our Privacy Policy. For information about our partners using advertising cookies on our site, please see the Partner List below. Origins It was revealed in the last few minutes of the Season 6 episode, Heartland (episode) that Gibbs's rules originated from his first AwCifCeE, SPhTa AnDnVoEn RGTibISbIsN,G w CheOrOeK sIhEeS told him at their first meeting that "Everyone needs a code they can live by". The only rule of Shannon's personal code that is quoted is either her first or third: "Never date a lumberjack." REJECT ADVERTISING COOKIES Years later, after their wedding, Gibbs began writing his rules down, keeping them in a small tin inside his home which was shown in the Season 7 finale episode, Rule Fifty-One (episode). -

The New History Comes to Town

New Mexico Historical Review Volume 69 Number 4 Article 7 10-1-1994 The New History Comes to Town Elizabeth Jameson Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr Recommended Citation Jameson, Elizabeth. "The New History Comes to Town." New Mexico Historical Review 69, 4 (1994). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr/vol69/iss4/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in New Mexico Historical Review by an authorized editor of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The New History Comes to Town ELIZABETH JAMESON An incongruous event at the 1990 annual conference of the Western History Association prefigured this special issue of the New Mexico Historical Review. The breakfast meeting of the Mining History Asso ciation was inadvertently scheduled in the same room with the American Society of Environmental History. Both groups tried to conduct their separate business amidst uneasy mutterings about "strange bedfellows." Nonetheless, forced to negotiate common terrain, the historians of an environmentally destructive industry broke bread, appropriately enough, with those who chronicle the devastation. The historical connections that were accidentally established in 1990 are consciously addressed by this issue's authors. Using the methods and conceptual frameworks of social and environmental histories, they connect the topics of mining technologies and economics, managerial organization; labor, environment and safety: and state policy. They leave behind the lone prospectors, the gold and silver, the bawdy boom towns of western lore, and take us instead to less romantic places that pro duced the copper, molybdenum, uranium, and coal required for twenti eth-century industries.