Graduate Recital: Taylor Dengler, Soprano

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’S Opera and Concert Arias Joshua M

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 10-3-2014 The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias Joshua M. May University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation May, Joshua M., "The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias" (2014). Doctoral Dissertations. 580. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/580 ABSTRACT The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias Joshua Michael May University of Connecticut, 2014 W. A. Mozart’s opera and concert arias for tenor are among the first music written specifically for this voice type as it is understood today, and they form an essential pillar of the pedagogy and repertoire for the modern tenor voice. Yet while the opera arias have received a great deal of attention from scholars of the vocal literature, the concert arias have been comparatively overlooked; they are neglected also in relation to their counterparts for soprano, about which a great deal has been written. There has been some pedagogical discussion of the tenor concert arias in relation to the correction of vocal faults, but otherwise they have received little scrutiny. This is surprising, not least because in most cases Mozart’s concert arias were composed for singers with whom he also worked in the opera house, and Mozart always paid close attention to the particular capabilities of the musicians for whom he wrote: these arias offer us unusually intimate insights into how a first-rank composer explored and shaped the potential of the newly-emerging voice type of the modern tenor voice. -

Magnificat in D Major, BWV

Johann Sebastian Bach Magnificat in D Major, BWV 243 Magnificat Quia respexit Quia fecit mihi magna Et misericordia eius Fecit potentiam Deposuit potentes Suscepit Israel Gloria patri Sicut erat in principio *** Chorus: S-S-A-T-B Soloists: Soprano 1, soprano 2, alto, tenor, bass Orchestra: 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 oboes d'amore, 3 trumpets, timpani, strings, continuo ************************* Program notes by Martin Pearlman Bach, Magnificat, BWV 243 In 1723, for his first Christmas as cantor of the St. Thomas Church in Leipzig, Bach presented a newly composed setting of the Magnificat. It was a grand, celebratory work with a five-voice chorus and a colorful variety of instruments, and Bach expanded the Magnificat text itself by interpolating settings of several traditional Christmas songs between movements. This was the original Eb-major version of his Magnificat, and it was Bach's largest such work up to that point. About a decade later, he reworked the piece, lowering the key from Eb to the more conventional trumpet key of D major, altering some of the orchestration, and, perhaps most importantly, removing the Christmas inserts, so that the work could be performed at a variety of festivals during the liturgical year. It is this later D major version of the Magnificat that is normally heard today. Despite its brilliance and grandeur, Bach's Magnificat is a relatively short work. Nonetheless, it is filled with countless fascinating details. The tenor opens his aria Deposuit with a violent descending F# minor scale to depict the text "He hath put down [the mighty]". At the end of the alto aria Esurientes, Bach illustrates the words "He hath sent the rich away empty" by having the solo flutes omit their final note. -

Rhythmic Foundation and Accompaniment

Introduction To Flamenco: Rhythmic Foundation and Accompaniment by "Flamenco Chuck" Keyser P.O. Box 1292 Santa Barbara, CA 93102 [email protected] http://users.aol.com/BuleriaChk/private/flamenco.html © Charles H. Keyser, Jr. 1993 (Painting by Rowan Hughes) Flamenco Philosophy IA My own view of Flamenco is that it is an artistic expression of an intense awareness of the existential human condition. It is an effort to come to terms with the concept that we are all "strangers and afraid, in a world we never made"; that there is probably no higher being, and that even if there is he/she (or it) is irrelevant to the human condition in the final analysis. The truth in Flamenco is that life must be lived and death must be faced on an individual basis; that it is the fundamental responsibility of each man and woman to come to terms with their own alienation with courage, dignity and humor, and to support others in their efforts. It is an excruciatingly honest art form. For flamencos it is this ever-present consciousness of death that gives life itself its meaning; not only as in the tragedy of a child's death from hunger in a far-off land or a senseless drive-by shooting in a big city, but even more fundamentally in death as a consequence of life itself, and the value that must be placed on life at each moment and on each human being at each point in their journey through it. And it is the intensity of this awareness that gave the Gypsy artists their power of expression. -

574040-41 Itunes Beethoven

BEETHOVEN Chamber Music Piano Quartet in E flat major • Six German Dances Various Artists Ludwig van ¡ Piano Quartet in E flat major, Op. 16 (1797) 26:16 ™ I. Grave – Allegro ma non troppo 13:01 £ II. Andante cantabile 7:20 BEE(1T77H0–1O827V) En III. Rondo: Allegro, ma non troppo 5:54 1 ¢ 6 Minuets, WoO 9, Hess 26 (c. 1799) 12:20 March in D major, WoO 24 ‘Marsch zur grossen Wachtparade ∞ No. 1 in E flat major 2:05 No. 2 in G major 1:58 2 (Grosser Marsch no. 4)’ (1816) 8:17 § No. 3 in C major 2:29 March in C major, WoO 20 ‘Zapfenstreich no. 2’ (c. 1809–22/23) 4:27 ¶ 3 • No. 4 in F major 2:01 4 Polonaise in D major, WoO 21 (1810) 2:06 ª No. 5 in D major 1:50 Écossaise in D major, WoO 22 (c. 1809–10) 0:58 No. 6 in G major 1:56 5 3 Equali, WoO 30 (1812) 5:03 º 6 Ländlerische Tänze, WoO 15 (version for 2 violins and double bass) (1801–02) 5:06 6 No. 1. Andante 2:14 ⁄ No. 1 in D major 0:43 No. 2 in D major 0:42 7 No. 2. Poco adagio 1:42 ¤ No. 3. Poco sostenuto 1:05 ‹ No. 3 in D major 0:38 8 › No. 4 in D minor 0:43 Adagio in A flat major, Hess 297 (1815) 0:52 9 fi No. 5 in D major 0:42 March in B flat major, WoO 29, Hess 107 ‘Grenadier March’ No. -

UWM Department of Music Concert Program Style Guide

UWM Department of Music Concert Program Style Guide Table of Contents 1. General Rules for All Titles 2. Generic Titles 3. Distinctive Titles 4. Composer Names & Dates 1. General Rules for All Titles 1.1 Titles (including movement titles) are capitalized following the rules of each language: a. English: capitalize all words except conjunctions, prepositions, and articles, unless they begin a title. b. French: capitalize all words up to and including the first noun; everything after that is lower case (except for proper nouns). c. German: capitalize first word, and all nouns. d. Italian & Spanish: capitalize first word, all else is lower case except proper nouns. 1.2 Movement Titles a. Movements follow under the main title; those in foreign languages should be italicized. b. Movement numbers are uppercase roman numerals (I, II, III, IV, rather than i, ii, iii, iv) c. If all movements of a work are performed in order, they do not need to be numbered; otherwise number the movements being performed with their original numbers. If only a few movements of many are being performed, it is possible to also add the word “Selections” in parentheses after the title to avoid confusion. Examples: Orchestral Suite No. 3 in D Major, BWV 1068 V. Bourrée VI. Gigue Carnaval des animaux (Selections) IV. Tortues XII. Fossiles d. It is appropriate to translate movement titles that might not otherwise be understood, particularly if they are not translated elsewhere in the program. Place translation(s) in parentheses. Example: Concerto for Orchestra I. Introduzione II. Gioco delle coppie (Game of Pairs) III. -

MTO 0.7: Alphonce, Dissonance and Schumann's Reckless Counterpoint

Volume 0, Number 7, March 1994 Copyright © 1994 Society for Music Theory Bo H. Alphonce KEYWORDS: Schumann, piano music, counterpoint, dissonance, rhythmic shift ABSTRACT: Work in progress about linearity in early romantic music. The essay discusses non-traditional dissonance treatment in some contrapuntal passages from Schumann’s Kreisleriana, opus 16, and his Grande Sonate F minor, opus 14, in particular some that involve a wedge-shaped linear motion or a rhythmic shift of one line relative to the harmonic progression. [1] The present paper is the first result of a planned project on linearity and other features of person- and period-style in early romantic music.(1) It is limited to Schumann's piano music from the eighteen-thirties and refers to score excerpts drawn exclusively from opus 14 and 16, the Grande Sonate in F minor and the Kreisleriana—the Finale of the former and the first two pieces of the latter. It deals with dissonance in foreground terms only and without reference to expressive connotations. Also, Eusebius, Florestan, E.T.A. Hoffmann, and Herr Kapellmeister Kreisler are kept gently off stage. [2] Schumann favours friction dissonances, especially the minor ninth and the major seventh, and he likes them raw: with little preparation and scant resolution. The sforzato clash of C and D in measures 131 and 261 of the Finale of the G minor Sonata, opus 22, offers a brilliant example, a peculiarly compressed dominant arrival just before the return of the main theme in G minor. The minor ninth often occurs exposed at the beginning of a phrase as in the second piece of the Davidsbuendler, opus 6: the opening chord is a V with an appoggiatura 6; as 6 goes to 5, the minor ninth enters together with the fundamental in, respectively, high and low peak registers. -

1 Ludwig Van Beethoven Symphony #9 in D Minor, Op. 125 2 Johann Sebastian Bach St. Matthew Passion

1 Ludwig van Beethoven Symphony #9 in D minor, Op. 125 2 Johann Sebastian Bach St. Matthew Passion "Ebarme dich, mein Gott" 3 George Frideric Handel Messiah: Hallelujah Chorus 4 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Symphony 41 C, K.551 "Jupiter" 5 Samuel Barber Adagio for Strings Op.11 6 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Clarinet Concerto A, K.622 7 Ludwig van Beethoven Piano Concerto 5 E-Flat, Op.73 "Emperor" (3) 8 Antonin Dvorak Symphony No 9 (IV) 9 George Gershwin Rhapsody In Blue (1924) 10 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Requiem in D minor K 626 (aeternam/kyrie/lacrimosa) 11 George Frideric Handel Xerxes - Largo 12 Johann Sebastian Bach Toccata And Fugue In D Minor, BWV 565 (arr Stokowski) 13 Ludwig van Beethoven Symphony No 5 in C minor Op 67 (I) 14 Johann Sebastian Bach Orchestral Suite #3 BWV 1068: Air on the G String 15 Antonio Vivaldi Concerto Grosso in E Op. 8/1 RV 269 "Spring" 16 Tomaso Albinoni Adagio in G minor 17 Edvard Grieg Peer Gynt 1, Op.46 18 Sergei Rachmaninov Piano Concerto No 2 in C minor Op 18 (I) 19 Ralph Vaughan Williams Lark Ascending 20 Gustav Mahler Symphony 5 C-Sharp Min (4) 21 Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky 1812 Overture 22 Jean Sibelius Finlandia, Op.26 23 Johann Pachelbel Canon in D 24 Carl Orff Carmina Burana: O Fortuna, In taberna, Tanz 25 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Serenade G, K.525 "Eine Kleine Nachtmusik" 26 Johann Sebastian Bach Brandenburg Concerto No 5 in D BWV 1050 (I) 27 Johann Strauss II Blue Danube Waltz, Op.314 28 Franz Joseph Haydn Piano Trio 39 G, Hob.15-25 29 George Frideric Handel Water Music Suite #2 in D 30 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Ave Verum Corpus, K.618 31 Johannes Brahms Symphony 1 C Min, Op.68 32 Felix Mendelssohn Violin Concerto in E minor, Op. -

Performance Commentary

PERFORMANCE COMMENTARY . It seems, however, far more likely that Chopin Notes on the musical text 3 The variants marked as ossia were given this label by Chopin or were intended a different grouping for this figure, e.g.: 7 added in his hand to pupils' copies; variants without this designation or . See the Source Commentary. are the result of discrepancies in the texts of authentic versions or an 3 inability to establish an unambiguous reading of the text. Minor authentic alternatives (single notes, ornaments, slurs, accents, Bar 84 A gentle change of pedal is indicated on the final crotchet pedal indications, etc.) that can be regarded as variants are enclosed in order to avoid the clash of g -f. in round brackets ( ), whilst editorial additions are written in square brackets [ ]. Pianists who are not interested in editorial questions, and want to base their performance on a single text, unhampered by variants, are recom- mended to use the music printed in the principal staves, including all the markings in brackets. 2a & 2b. Nocturne in E flat major, Op. 9 No. 2 Chopin's original fingering is indicated in large bold-type numerals, (versions with variants) 1 2 3 4 5, in contrast to the editors' fingering which is written in small italic numerals , 1 2 3 4 5 . Wherever authentic fingering is enclosed in The sources indicate that while both performing the Nocturne parentheses this means that it was not present in the primary sources, and working on it with pupils, Chopin was introducing more or but added by Chopin to his pupils' copies. -

AP Music Theory: Unit 2

AP Music Theory: Unit 2 From Simple Studies, https://simplestudies.edublogs.org & @simplestudiesinc on Instagram Music Fundamentals II: Minor Scales and Key Signatures, Melody, Timbre, and Texture Minor Scales ● Natural Minor ○ No accidentals are changed from the relative minor’s key signature ○ Scale Pattern: W H W W H W W (W=whole note; H=half note) ○ Solfege: Do Re Mi Fa Sol La Ti Do ○ Scale Degrees: 1 2 b3 4 5 b6 b7 8 ● Harmonic Minor ○ The seventh scale degree is raised (it becomes the leading tone) ○ Scale Pattern: W H W W H m3 H ○ Solfege: Do Re Mi Fa Sol La Ti Do ○ Scale Degrees: 1 2 b3 4 5 b6 7 8 ● Melodic Minor ○ Ascending: the sixth and seventh degrees are raised ○ Descending: it becomes natural minor (meaning that the sixth and seventh degrees are no longer raised) ○ Scale Pattern (Ascending): W H W W W W H ○ Solfege (Ascending): Do Re Mi Fa Sol La Ti Do ○ Solfege (Descending): Do Te Le Sol Fa Mi Re Do ○ Scale Degrees (Ascending): 1 2 b3 4 5 6 7 8 ● Minor Pentatonic Scale ○ 5-note minor scale (made of the 5 diatonic pitches) ○ Scale Pattern: m3 W W m3 W ○ Solfege: Do Mi Fa Sol Te Do ○ Scale Degrees 1 b3 4 5 b7 8 Key Relationships ● Parallel Keys ○ Keys that share a tonic ○ One major and one minor ■ Example: d minor and D major are parallel keys because they share the same tonic (D) ● Relative Keys ○ Keys that share a key signature (but have different tonics) ■ Example: a minor and C major are relative keys (since they both don’t have any sharps or flats) ● Closely Related Keys ○ Keys that differ from each other by at most -

Key Relationships in Music

LearnMusicTheory.net 3.3 Types of Key Relationships The following five types of key relationships are in order from closest relation to weakest relation. 1. Enharmonic Keys Enharmonic keys are spelled differently but sound the same, just like enharmonic notes. = C# major Db major 2. Parallel Keys Parallel keys share a tonic, but have different key signatures. One will be minor and one major. D minor is the parallel minor of D major. D major D minor 3. Relative Keys Relative keys share a key signature, but have different tonics. One will be minor and one major. Remember: Relatives "look alike" at a family reunion, and relative keys "look alike" in their signatures! E minor is the relative minor of G major. G major E minor 4. Closely-related Keys Any key will have 5 closely-related keys. A closely-related key is a key that differs from a given key by at most one sharp or flat. There are two easy ways to find closely related keys, as shown below. Given key: D major, 2 #s One less sharp: One more sharp: METHOD 1: Same key sig: Add and subtract one sharp/flat, and take the relative keys (minor/major) G major E minor B minor A major F# minor (also relative OR to D major) METHOD 2: Take all the major and minor triads in the given key (only) D major E minor F minor G major A major B minor X as tonic chords # (C# diminished for other keys. is not a key!) 5. Foreign Keys (or Distantly-related Keys) A foreign key is any key that is not enharmonic, parallel, relative, or closely-related. -

A Countertenor's Reference Guide to Operatic Repertoire

A COUNTERTENOR’S REFERENCE GUIDE TO OPERATIC REPERTOIRE Brad Morris A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC May 2019 Committee: Christopher Scholl, Advisor Kevin Bylsma Eftychia Papanikolaou © 2019 Brad Morris All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Christopher Scholl, Advisor There are few resources available for countertenors to find operatic repertoire. The purpose of the thesis is to provide an operatic repertoire guide for countertenors, and teachers with countertenors as students. Arias were selected based on the premise that the original singer was a castrato, the original singer was a countertenor, or the role is commonly performed by countertenors of today. Information about the composer, information about the opera, and the pedagogical significance of each aria is listed within each section. Study sheets are provided after each aria to list additional resources for countertenors and teachers with countertenors as students. It is the goal that any countertenor or male soprano can find usable repertoire in this guide. iv I dedicate this thesis to all of the music educators who encouraged me on my countertenor journey and who pushed me to find my own path in this field. v PREFACE One of the hardships while working on my Master of Music degree was determining the lack of resources available to countertenors. While there are opera repertoire books for sopranos, mezzo-sopranos, tenors, baritones, and basses, none is readily available for countertenors. Although there are online resources, it requires a great deal of research to verify the validity of those sources. -

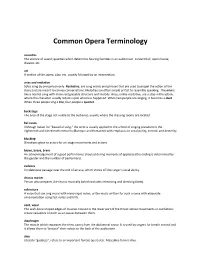

Common Opera Terminology

Common Opera Terminology acoustics The science of sound; qualities which determine hearing facilities in an auditorium, concert hall, opera house, theater, etc. act A section of the opera, play, etc. usually followed by an intermission. arias and recitative Solos sung by one person only. Recitative, are sung words and phrases that are used to propel the action of the story and are meant to convey conversations. Melodies are often simple or fast to resemble speaking. The aria is like a normal song with more recognizable structure and melody. Arias, unlike recitative, are a stop in the action, where the character usually reflects upon what has happened. When two people are singing, it becomes a duet. When three people sing a trio, four people a quartet. backstage The area of the stage not visible to the audience, usually where the dressing rooms are located. bel canto Although Italian for “beautiful song,” the term is usually applied to the school of singing prevalent in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (Baroque and Romantic) with emphasis on vocal purity, control, and dexterity blocking Directions given to actors for on-stage movements and actions bravo, brava, bravi An acknowledgement of a good performance shouted during moments of applause (the ending is determined by the gender and the number of performers). cadenza An elaborate passage near the end of an aria, which shows off the singer’s vocal ability. chorus master Person who prepares the chorus musically (which includes rehearsing and directing them). coloratura A voice that can sing music with many rapid notes, or the music written for such a voice with elaborate ornamentation using fast notes and trills.