The Ties That Bind: University Nostalgia Fosters Relational and Collective University Engagement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Excesss Karaoke Master by Artist

XS Master by ARTIST Artist Song Title Artist Song Title (hed) Planet Earth Bartender TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIM ? & The Mysterians 96 Tears E 10 Years Beautiful UGH! Wasteland 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants Belief) More Than This 2 Chainz Bigger Than You (feat. Drake & Quavo) [clean] Trouble Me I'm Different 100 Proof Aged In Soul Somebody's Been Sleeping I'm Different (explicit) 10cc Donna 2 Chainz & Chris Brown Countdown Dreadlock Holiday 2 Chainz & Kendrick Fuckin' Problems I'm Mandy Fly Me Lamar I'm Not In Love 2 Chainz & Pharrell Feds Watching (explicit) Rubber Bullets 2 Chainz feat Drake No Lie (explicit) Things We Do For Love, 2 Chainz feat Kanye West Birthday Song (explicit) The 2 Evisa Oh La La La Wall Street Shuffle 2 Live Crew Do Wah Diddy Diddy 112 Dance With Me Me So Horny It's Over Now We Want Some Pussy Peaches & Cream 2 Pac California Love U Already Know Changes 112 feat Mase Puff Daddy Only You & Notorious B.I.G. Dear Mama 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt I Get Around 12 Stones We Are One Thugz Mansion 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says Until The End Of Time 1975, The Chocolate 2 Pistols & Ray J You Know Me City, The 2 Pistols & T-Pain & Tay She Got It Dizm Girls (clean) 2 Unlimited No Limits If You're Too Shy (Let Me Know) 20 Fingers Short Dick Man If You're Too Shy (Let Me 21 Savage & Offset &Metro Ghostface Killers Know) Boomin & Travis Scott It's Not Living (If It's Not 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls With You 2am Club Too Fucked Up To Call It's Not Living (If It's Not 2AM Club Not -

All Around the World the Global Opportunity for British Music

1 all around around the world all ALL British Music for Global Opportunity The AROUND THE WORLD CONTENTS Foreword by Geoff Taylor 4 Future Trade Agreements: What the British Music Industry Needs The global opportunity for British music 6 Tariffs and Free Movement of Services and Goods 32 Ease of Movement for Musicians and Crews 33 Protection of Intellectual Property 34 How the BPI Supports Exports Enforcement of Copyright Infringement 34 Why Copyright Matters 35 Music Export Growth Scheme 12 BPI Trade Missions 17 British Music Exports: A Worldwide Summary The global music landscape Europe 40 British Music & Global Growth 20 North America 46 Increasing Global Competition 22 Asia 48 British Music Exports 23 South/Central America 52 Record Companies Fuel this Global Success 24 Australasia 54 The Story of Breaking an Artist Globally 28 the future outlook for british music 56 4 5 all around around the world all around the world all The Global Opportunity for British Music for Global Opportunity The BRITISH MUSIC IS GLOBAL, British Music for Global Opportunity The AND SO IS ITS FUTURE FOREWORD BY GEOFF TAYLOR From the British ‘invasion’ of the US in the Sixties to the The global strength of North American music is more recent phenomenal international success of Adele, enhanced by its large population size. With younger Lewis Capaldi and Ed Sheeran, the UK has an almost music fans using streaming platforms as their unrivalled heritage in producing truly global recording THE GLOBAL TOP-SELLING ARTIST principal means of music discovery, the importance stars. We are the world’s leading exporter of music after of algorithmically-programmed playlists on streaming the US – and one of the few net exporters of music in ALBUM HAS COME FROM A BRITISH platforms is growing. -

DUA LIPA We're Good and Future Nostalgia the MOONLIGHT EDITION

DUA LIPA RELEASES NEW SINGLE 'WE’RE GOOD’ TAKEN FROM ‘FUTURE NOSTALGIA - THE MOONLIGHT EDITION’ BOTH OUT TODAY Today, Dua Lipa releases her new single ‘We’re Good’; dropping the tempo the track is a sensual tale of two lovers needing to go their separate ways. Produced by Sly this slow groove track is taken from ‘Future Nostalgia - The Moonlight Edition, which also includes the hit singles ‘Don’t Start Now’, ‘Physical’, ‘Break My Heart’ and ‘Levitating’ The video for ‘We're Good’ sees Dua Lipa serenading the guests in an exquisite looking restaurant on a ship from the turn of the 20th Century. In the same restaurant a lobster’s fate takes a very unexpected turn too….. The beautiful and surreal video is directed by Vania Hetmann & Gal Muggla. ‘Future Nostalgia - The Moonlight Edition’ is also released today on all digital platforms. This deluxe edition features three more previously unheard tracks ‘If It Ain’t Me’, ‘That Kind of Women’ and ‘Not My Problem (feat. JID)’ and will include the top 10 smash hit single from Miley Cyrus Feat Dua Lipa ‘Prisoner’ which has reached 250m streams worldwide. Also on the album is ‘Fever’ with Angèle, which spent three weeks at #1 in France and 11 weeks at #1 in Belgium and J Balvin, & Bad Bunny ‘UN DIA (ONE DAY) (Feat. Tainy) which has hit over 500m streams. Full track listing Future Nostalgia - The Moonlight Edition 1. Future Nostalgia 2. Don’t Start Now 3. Cool 4. Physical 5. Levitating 6. Pretty Please 7. Hallucinate 8. Love Again 9. -

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind. -

The Echo: May 6, 2020

5/6/2020, 9:00AM Dua Lipa brings back the ‘80s ‘Future Nostalgia’ offers feel-good disco-pop By HOLLY GASKILL “Future Nostalgia” draws on both the ’80s and present day in Dua Lipa’s new album Right now might be the weirdest time to drop a disco- pop dance album, yet “Future Nostalgia” rises to the impossible task. Throughout the album, singer Dua Lipa incorporates classic ’80s disco tropes of a strong baseline beat and contrasting syncopation. Adding to the danceability, the layers are introduced in stagger as if it were being mixed live by a DJ. “Future Nostalgia” was designed to mimic a live party for whenever and wherever — how timely. While this album stands out as a thoughtful and complete work, Lipa has come a long way to this point. As a waitress in England, Lipa was discovered for her singing ability and released her xrst album in 2017. Although it was a successful premiere of her distinct deeper singing voice and star-studded with featuring artists, it lacked cohesion and direction. It was someone trying to xnd their sound. In contrast, “Future Nostalgia” shows intention around every turn. “You want a timeless song, I want to change the game,” Lipa sings as the xrst lyrics on the album. The title itself is riddled with double-meaning. Because of the ’80s inyuences, “Future Nostalgia” is xrst an allusion to the nostalgic music brought to the present- day. However, “Future Nostalgia” is also emblematic of where pop music is heading. As evidence of this, The Weeknd also released a chart- topping album, “After Hours,” that shows ‘80s pop inyuences on March 20. -

Coca-Cola Stage Backgrounder 2016

May 26, 2016 BACKGROUNDER 2016 Coca-Cola Stage lineup Christian Hudson Appearing Thursday, July 7, 7 p.m. Website: http://www.christianhudsonmusic.com/ Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/ChristianHudsonMusic Twitter: www.twitter.com/CHsongs While most may know Christian Hudson by his unique and memorable performances at numerous venues across Western Canada, others seem to know him by his philanthropy. This talented young man won the prestigious Calgary Stampede Talent Show last summer but what was surprising to many was he took his prize money of $10,000 and donated it all to the local drop-in centre. He was touched by the stories he was told by a few people experiencing homelessness he had met one night prior to the contest’s finale. His infectious originals have caught the ears of many in the industry that are now assisting his career. He was honoured to receive 'The Spirit of Calgary' Award at the inaugural Vigor Awards for his generosity. Hudson will soon be touring Canada upon the release of his first single on national radio. JJ Shiplett Appearing Thursday, July 7, 8 p.m. Website: http://www.jjshiplettmusic.com/ Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/jjshiplettmusic/ Twitter: www.twitter.com/jjshiplettmusic Rugged, raspy and reserved, JJ Shiplett is a true artist in every sense of the word. Unapologetically himself, the Alberta born singer-songwriter and performer is both bold in range and musical creativity and has a passion and reverence for the art of music and performance that has captured the attention of music fans across the country. He spent the major part of early 2016 as one of the opening acts on the Johnny Reid tour and is also signed to Johnny Reid’s company. -

Final Nominations List the National Academy of Recording Arts & Sciences, Inc

NATIONAL ACADEMY OF RECORDING ARTS & SCIENCES, INC. FINAL NOMINATIONS LIST THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OF RECORDING ARTS & SCIENCES, INC. Final Nominations List 63rd Annual GRAMMY® Awards For recordings released during the Eligibility Year September 1, 2019 through August 31, 2020 Note: More or less than 5 nominations in a category is the result of ties. General Field Category 1 8. SAVAGE Record Of The Year Megan Thee Stallion Featuring Beyoncé Award to the Artist and to the Producer(s), Recording Engineer(s) Beyoncé & J. White Did It, producers; Eddie “eMIX” and/or Mixer(s) and mastering engineer(s), if other than the artist. Hernández, Shawn "Source" Jarrett, Jaycen Joshua & Stuart White, engineers/mixers; Colin Leonard, mastering 1. BLACK PARADE engineer Beyoncé Beyoncé & Derek Dixie, producers; Stuart White, engineer/mixer; Colin Leonard, mastering engineer 2. COLORS Black Pumas Adrian Quesada, producer; Adrian Quesada, engineer/mixer; JJ Golden, mastering engineer 3. ROCKSTAR DaBaby Featuring Roddy Ricch SethinTheKitchen, producer; Derek "MixedByAli" Ali, Chris Dennis, Liz Robson & Chris West, engineers/mixers; Glenn A Tabor III, mastering engineer 4. SAY SO Doja Cat Tyson Trax, producer; Clint Gibbs & Kalani Thompson, engineers/mixers; Mike Bozzi, mastering engineer 5. EVERYTHING I WANTED Billie Eilish Finneas O'Connell, producer; Rob Kinelski & Finneas O'Connell, engineers/mixers; John Greenham, mastering engineer 6. DON'T START NOW Dua Lipa Caroline Ailin & Ian Kirkpatrick, producers; Josh Gudwin, Drew Jurecka & Ian Kirkpatrick, engineers/mixers; Chris Gehringer, mastering engineer 7. CIRCLES Post Malone Louis Bell, Frank Dukes & Post Malone, producers; Louis Bell & Manny Marroquin, engineers/mixers; Mike Bozzi, mastering engineer © The Recording Academy 2020 - all rights reserved 1 Not for copy or distribution 63rd Finals - Press List General Field Category 2 8. -

Midyear Report Canada 2020

NIELSEN MUSIC / MRC DATA MIDYEAR REPORT CANADA 2020 1 Introduction HAT A DIFFERENCE A FEW MONTHS MAKE. IT’S HARD TO BELIEVE THAT IT WASN’T even six months ago that Shakira and Jennifer Lopez performed for a tightly packed crowd of more than 60,000 people in Miami at the Super Bowl, while Billie Eilish and her brother Finneas picked up five Grammys at what turned out to be 2020’s last major music business gathering since COVID-19 halted live events. WBy Friday, March 13, the NBA and NHL had suspended play, the NCAA had canceled its spring tournaments, and theaters and live music venues had closed. As “safer at home” orders spread throughout the country, our homes became our offices, our schools, our daycares and our social hubs. Quickly and dramatically, life had changed. Our routines were disrupted, and we struggled to find balance. Still, the music industry was experiencing a strong start to the year. Audio streaming was growing through early March, up 20.9% over the same period in 2019. Total music consumption was up 10.8% in the first 10 weeks of the year. As working from home became a reality for many, some of the key music listening hours, such as during commutes, were disrupted. But one thing that has remained consistent as the pandemic has unfolded is entertainment’s place in helping consumers escape, relax and feel energized. In fact, in our recent consumer research studies, 73% of people said they would go crazy without entertainment during this time. Then, just as many communities began to slowly reopen, the country was shaken by the senseless May 25 killing of George Floyd by Minneapolis police. -

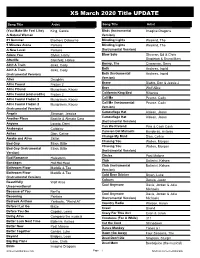

XS March 2020 Title UPDATE

XS March 2020 Title UPDATE Song Title Artist Song Title Artist (You Make Me Feel Like) King, Carole Birds (Instrumental Imagine Dragons A Natural Woman Version) 21 Summer Brothers Osbourne Blinding Lights Weeknd, The 5 Minutes Alone Pantera Blinding Lights Weeknd, The A New Level Pantera (Instrumental Version) Adore You Styles, Harry Blow Solo Sheeran, Ed & Chris Afterlife Steinfeld, Hailee Stapleton & Bruno Mars Bonny, The Ain't A Train Jinks, Cody Cinnamon, Gerry Both Ain't A Train Jinks, Cody Andress, Ingrid (Instrumental Version) Both (Instrumental Andress, Ingrid Version) Alive Daughtry Brave All is Found Frozen 2 Diablo, Don & Jessie J Bros All is FOund Musgraves, Kacey Wolf Alice California King Bed All is Found (end credits) Frozen 2 Rihanna Call Me All is Found Frozen 2 Musgraves, Kacey Pearce, Carly Call Me (Instrumental All is Found Frozen 2 Musgraves, Kacey Pearce, Carly (Instrumental Version) Version) Camouflage Hat Angels Simpson, Jessica Aldean, Jason Camouflage Hat Another Place Bastille & Alessia Cara Aldean, Jason (Instrumental Version) Anyone Lovato, Demi Can We Pretend Pink & Cash Cash Arabesque Coldplay Cancion Del Mariachi Banderas, Antonio Ashes Dion, Celine Change My Mind Dion, Celine Awake and Alive Skillet Chasing You Wallen, Morgan Bad Guy Eilish, Billie Chasing You Wallen, Morgan Bad Guy (Instrumental Eilish, Billie (Instrumental Version) Version) Circles Post Malone Bad Romance Halestorm Club Ballerini, Kelsea Bandages Hot Hot Heat Club (Instrumental Ballerini, Kelsea Bathroom Floor Maddie & Tae Version) Bathroom -

DUA LIPA FUTURE NOSTALGIA VIRTUAL EVENT” Promotion Terms and Conditions

Warner Music Australia Pty Limited “DUA LIPA FUTURE NOSTALGIA VIRTUAL EVENT” Promotion Terms and Conditions By entering Warner Music Australia Pty Limited’s (“Warner”) “DUA LIPA FUTURE NOSTALGIA VIRTUAL EVENT” Promotion you are agreeing to the following terms and conditions: 1. STANDARD TERMS 1.1 Information and instructions on "How to Enter” form part of these conditions of entry. By entering the Promotion, entrants accept and agree to be bound by these conditions of entry. 2. WHO CAN ENTER? 2.1 The only persons who may enter and be awarded the prize are those who: a) are residents of Australia; and b) are 18 years of age or older c) have a valid email address; and d) are not employees of the Promoter or their associated companies, agencies or families. 3. THE PROMOTION 3.1 The Promotion is known as the “DUA LIPA FUTURE NOSTALGIA VIRTUAL EVENT” Promotion. 4. HOW TO ENTER 4.1 The Promotion will run between 1 September 2020 at 5.00pm (AEST) and 9 September 2020 at 4.00pm (AEST) (“the Promotion Period”). 4.2 To enter, (a) Step 1 Go to the url https://fpt.fm/app/25071/dua-lipa-heaps-gay-ftw (“the Competition Page”); (b) Step 2: Follow the prompts on the Competition Page and login to your Spotify account or use your personal Facebook Connect to login to your Spotify account and accept the terms and conditions. (c) Step 3: Save the Dua Lipa album entitled “Club Future Nostalgia (DJ Mix)” on Spotify (“the Artist’s Spotify Album”) (compulsory); When you save the Artist’s Spotify Album on Spotify, the following information will be collected from your Spotify account: your registration data (name, username, email address, date of birth, gender, postal code and country). -

Rock Album Discography Last Up-Date: September 27Th, 2021

Rock Album Discography Last up-date: September 27th, 2021 Rock Album Discography “Music was my first love, and it will be my last” was the first line of the virteous song “Music” on the album “Rebel”, which was produced by Alan Parson, sung by John Miles, and released I n 1976. From my point of view, there is no other citation, which more properly expresses the emotional impact of music to human beings. People come and go, but music remains forever, since acoustic waves are not bound to matter like monuments, paintings, or sculptures. In contrast, music as sound in general is transmitted by matter vibrations and can be reproduced independent of space and time. In this way, music is able to connect humans from the earliest high cultures to people of our present societies all over the world. Music is indeed a universal language and likely not restricted to our planetary society. The importance of music to the human society is also underlined by the Voyager mission: Both Voyager spacecrafts, which were launched at August 20th and September 05th, 1977, are bound for the stars, now, after their visits to the outer planets of our solar system (mission status: https://voyager.jpl.nasa.gov/mission/status/). They carry a gold- plated copper phonograph record, which comprises 90 minutes of music selected from all cultures next to sounds, spoken messages, and images from our planet Earth. There is rather little hope that any extraterrestrial form of life will ever come along the Voyager spacecrafts. But if this is yet going to happen they are likely able to understand the sound of music from these records at least. -

Dua Lipa - New Rules (Official Music Video)

Dua Lipa - New Rules (Official Music Video) One, one, one, one, one... Talkin' in my sleep at night, makin' myself crazy (Out of my mind, out of my mind) Wrote it down and read it out, hopin' it would save me (Too many times, too many times) My love, he makes me feel like nobody else, nobody else But my love, he doesn't love me, so I tell myself, I tell myself One: Don't pick up the phone You know he's only callin' 'cause he's drunk and alone Two: Don't let him in You'll have to kick him out again Three: Don't be his friend You know you're gonna wake up in his bed in the morning And if you're under him, you ain't gettin' over him I got new rules, I count 'em I got new rules, I count 'em I gotta tell them to myself I got new rules, I count 'em I gotta tell them to myself I keep pushin' forwards, but he keeps pullin' me backwards (Nowhere to turn, no way) (Nowhere to turn, no) Now I'm standin' back from it, I finally see the pattern (I never learn, I never learn) But my love, he doesn't love me, so I tell myself, I tell myself I do, I do, I do One: Don't pick up the phone You know he's only callin' 'cause he's drunk and alone Two: Don't let him in You'll have to kick him out again Three: Don't be his friend You know you're gonna wake up in his bed in the morning And if you're under him, you ain't gettin' over him I got new rules, I count 'em I got new rules, I count 'em I gotta tell them to myself I got new rules, I count 'em I gotta tell them to myself Practice makes perfect I'm still tryna learn it by heart (I got new rules, I count 'em) Eat, sleep, and breathe it Rehearse and repeat it, 'cause I..