Sonny Montes and Mexican American Activism in Oregon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Movimiento Art Chicano Public Art in the 1970’S

Movimiento Art Chicano Public Art in the 1970’s Frank Hinojsa. Chicanismo, mural executed with student assistants, acrylic, auditorium, Northwest Rural Opportunities, Pasco, WA., 1975, 8 x 15 ft. Photographed by Bob Haft. A visual dictionary of Chicano art, this mural presents a survey of Movimiento iconography through the inclusion of Chicano racial, political and cultural symbols. Produced with local high school students assisting the artist, it is an important public work rich in cultural content. The largest proportion of Chicano murals in the Northwest are located in social services agencies which include Northwest Rural Opportunities, El Centro de la Raza and educational institutions. Major mural and poster production centers were El Centro de la Raza, and the University of Washington, in Seattle, and Colegio César Chávez, Mt. Angel, Oregon. All Chicano murals in the Pacific Northwest except three are indoors. The art of the Movimiento has yet to Pedro Rodríguez, El Saber Es La Libertad, (detail), become a recognized and visible part of mural, lobby, Northwest Rural Opportunities, Granger, Wa., 1976, 8 x 11 ft. Commissioned by the Pacific Northwest art history. Addressed to Washington State Arts Commission and the Office the needs of a struggling minority communi- of the State Superintendent of Public Instruction. ty, rather than to the mainstream art world, Photographed by Bob Haft. Northwest Chicano art was shaped by goals and approaches that transcended regional Rodríquez’s mural presents a symbol that appears boundaries. Ideas and stimulation came, frequently in movimiento art: the three-faced directly or indirectly, from many sources: mestizo image symbolizes the fusion of the Spaniard pre-Columbian art; vernacular art forms; and the Indian into the central figure of the Chicano. -

Mexican-Americans in the Pacific Northwest, 1900--2000

UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations 1-1-2006 The struggle for dignity: Mexican-Americans in the Pacific Northwest, 1900--2000 James Michael Slone University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/rtds Repository Citation Slone, James Michael, "The struggle for dignity: Mexican-Americans in the Pacific Northwest, 1900--2000" (2006). UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations. 2086. http://dx.doi.org/10.25669/4kwz-x12w This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE STRUGGLE FOR DIGNITY: MEXICAN-AMERICANS IN THE PACIFIC NORTHWEST, 1900-2000 By James Michael Slone Bachelor of Arts University of Nevada, Las Vegas 2000 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment Of the requirements for the Master of Arts Degree in History Department of History College of Liberal Arts Graduate College University of Nevada, Las Vegas May 2007 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number: 1443497 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. -

César Chávez Elementary School CCE Family Handbook

César Chávez Elementary School 1221 Anderson Road Davis, CA 95616 (530) 757-5490 CCE Family Handbook iSí Se Puede! 2020-2021 Office Hours Open to the Public: Mondays, Wednesdays, Fridays - 8am-3:30pm Our Mission To develop socially responsible lifelong learners who embrace multiculturalism, Spanish and English biliteracy and bilingualism. Our Motto iSí Se Puede! Our Core-Values CARES: Cooperación, Adaptabilidad, Responsabilidad, Empatía, Seguridad Dear CCE Students and Families, Welcome to César Chávez Elementary (CCE) School and our Spanish Immersion Program! We are very excited to launch the 2020-21 school year in a Distance Learning instructional model that will focus on Spanish Language Development, academic interventions and opportunities to engage in meaningful activities that are connected to our students’ lives. We plan to teach and support your child in a seven-year journey enriched with academic Spanish language acquisition, social-emotional development lessons and 21st Century skills! This CCE Family Handbook is designed to provide you with all the necessary information to support our school’s vision, mission and goals. Parents please take the time to read and discuss Section 1 in this Handbook with your child/children. Section 2 is provided for parents and staff that reviews district and school policies protocols, including background and information about CCE’s Spanish Immersion Program. Please keep your CCE Family Handbook in an accessible manner throughout the school year. You can access a digital copy on our CCE website https://cesarchavez.djusd.net/, or request a hardcopy from our office staff to be delivered to you within five days. Research shows that students’ academic and socio-emotional success rates improve when there is a positive home- school connection with staff, peers and families. -

Chicanos in Oregon: an Historical Overview

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 7-1974 Chicanos in Oregon: An historical overview Richard Wayne Slatta Portland State University Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: http://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Slatta, Richard Wayne, "Chicanos in Oregon: An historical overview" (1974). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 2059. 10.15760/etd.2058 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. \ AN ABSTRACT 014' THE THESIS OF RichaI'd l{[ayne Slat"ta for the I • t N~ster ·of ~rts in History presented July 25, 1974. Titles Chicanos in Oregon, An Historical Overview. APPROVED BY ~ffiMBERS OF THE THESIS COMr~TTEEs Vict~r C. Dahl, Chairman . N1.lnn Spaniards were the first Europeans to explore the Pacific Northwest coastline, but the only ~vidence of these early visits is a sprinkling of Spanish place names commem orating the intrepid voyagers. The more than four centuries of. recorded history since that time are nearly devoid, of references to Spanish-speaking people, esp~cially Mexicans and Americans of Me'xican descent (Chicanos). Even the heavy influx of Ch~cano migrant farm workers in the 1950's and 1960·5 fail~d to attraQt the attention of historians or 80- cial science resaarchers. By 1970, the Sp~lish-lang~age population had become Oregon's largest ethnic oincrity and . -

OSU Libraries Internship Program Project and Position Description

OSU Libraries – Special Collections & Archives Research Center Oregon State University, 121 The Valley Library, Corvallis, Oregon 97331-4501 T 541-737-2075 | F 541-737-8674| http://scarc.library.oregonstate.edu/ OSU Libraries Internship Program Project and Position Description Project Colegio César Chávez Collection Online and Physical Dual Language Exhibits Description of the Internship Project The intern will create a dual language (English and Spanish) online exhibit of the Colegio César Chávez Collection using the web publishing software Omeka; the intern will also curate a small, dual language physical exhibit. The Colegio César Chávez was established in 1973 as a four year Chicano serving institution in Mount Angel, Oregon; it closed a decade later in 1983. The collection consists of materials belonging Arthur and Karen Olivo and their son Andrew Parodi; the Olivo family lived on the grounds of the college campus between 1980-1982. Arthur Olivo was both a student at the Colegio and the campus groundskeeper. The collection materials include publications, correspondence, a bilingual college catalog, a Mount Angel College Yearbook, and photographs. For more information about the collection see the collection finding aid: http://archives.library.oregonstate.edu/files/archives/OREcolegio.pdf and the oral history interview with Karen Olivo and Andrew Parodi conducted in the summer of 2012: http://wpmu.library.oregonstate.edu/oregon-multicultural- archives/2013/04/09/colegio-oralhistory/ Project Schedule and Timeline 1 of 2 options: Summer -

UFW Information and Research Department Records

UFW Information and Research Department Papers, 1939-1978 (Predominantly 1970-77) 32.5 linear feet 32 Storage Boxes 1 Manuscript Box Accession # 221 OCLC # DALNET # In 1962 The National Farm Workers Association (NFWA) was founded at a convention called by Cesar Chavez. This organization affiliated with the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee in 1966 to become the United Farm Workers Organizing Committee (UFWOC). In 1972 the UFWOC became independent of the AFL-CIO and in one year later changed its name to the United Farm Workers, AFL-CIO. The UFW has been led by Cesar Chavez since 1962. The Information and Research Department of the UFW collects the materials of the union and retains them for research purposes. In addition to union generated materials, the department also collects papers of interest to Farm Workers from other areas. Important subjects in the collection: Agriculture Legislation and Elections concerning Boycotts Farm Labor California Negotiations for Contracts Farm Labor Philippines Grapes Strikes Immigration Teamsters Union Lettuce Important correspondents in the collection: Joan Baez Edward F. Kennedy Governor Edmund Brown Coretta Scott King Jimmy Carter Mack Lyons Marshall Ganz Fred Ross Dolores Huerta Larry Tramutt Larry Itliong Pete Velasco Non-Manuscript Material Some photographs, audio tapes and posters have been placed in the Archives Audio-Visual Collection, and a few copies of El Malcriado may be found in the Archives Library. 1 UFW Information and Research Department Collection - 2 - PLEASE NOTE: Folders are computer-arranged alphabetically in this finding aid, but may actually be dispersed throughout several boxes in the collection. Note carefully the box number for each folder heading. -

Program Eastern Washington University Portland State University Portland

RISTED BY THE PACIFIC NORTHWEST FOCO / • - .aM-r '.'.r ;NTY-SEVENTH ANNUAL NATIONAL CONFERENCE »w - -;>; 'tj' SABIDU YOUTH, CO ;> A'.ST- ;*•-/> r' •#• rvc^irm/naccs / /W i»> • >»Miitfi.Mi).Vriiiiiiiiii.. II I TOwk HILTON • POBTLAND OREOO^ Loeo OfSIStti ANDII£S BAIfeAJAS / WEB PROORAMMiNO. SANTOS CASH CONFERENCE EVENT MAP FOR HILTON HOTEL DIRECTORS THE TWENTY-SEVENTH ANNUAL SENATE EXECUTIVE B B NATIONAL CONFERENCE THIRD LEVEL PAVILION BALLROOM ^ EAST KAVILIUN I i BALLROOM / \ \ "EST II i J II ]mi•JII— MJ LB TiB• •} (i- 1J .t PLAZA LEVEL 1 FT PARLOR F A PARLOR GRAND BALLROOM L/LL • »ARLOR I ' C • SABIDURIA, LUCHA Y LIBERACION: YOUTH, COMMUNITY S. CULTURE EN EL NUEVO SOL B BALLROOM LEVEL TABLE OF CONTENTS I The National Association for Chicana and Chicano Studies 1 INTRODUCTIONS (NACCS) was founded in 1972 to encourage research to further the political actualization of the Chicana and Chicano community. NACCS calls for committed, critical, and rigorous 1 Welcome Letters 2 1 research. NACCS was envisioned not as an academic 1 Dedications k 1 embellishment, but as a structure rooted in political life. 6 1 From its inception, NACCS presupposed a divergence from 1 National Coordinating Confimittee mainstream academic research. We recognize that 1 Conference Organizing Connnnittee 7 1 mainstream research, based on an integrationist perspective emphasizing consensus, assimilation, and the legitimacy of 1 Conference Sponsors 8 1 society's institutions, has obscured and distorted the 1 Vendors and Exhibitors 9 1 significant historical roles class, race, gender, sexuality and group interests have played in shaping our existence as a 1 Hotel Infornnation 10 1 people. -

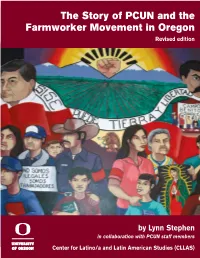

The Story of PCUN and the Farmworker Movement in Oregon Revised Edition

The Story of PCUN and the Farmworker Movement in Oregon Revised edition by Lynn Stephen in collaboration with PCUN staff members Center for Latino/a and Latin American Studies (CLLAS) The STory of PCUN aNd The farmworker movement iN oregoN Revised and Expanded by Lynn Stephen in collaboration with PCUN staff and members Center for Latino/a and Latin American Studies (CLLAS) Eugene, Oregon July 2012 Front cover photograph: Mural in the meeting hall of PCUN’s Risberg Hall headquarters, Woodburn, Oregon. Title page photograph: Tenth Anniversary Organizing Campaign, Brooks, Oregon, June 1995. Back cover: Mural on back wall of the meeting hall of PCUN’s Risberg Hall headquarters, Woodburn, Oregon. © Lynn Stephen and pCUn, 2012 Written by Lynn Stephen in collaboration with PCUN staff and members Center for Latino/a and Latin American Studies (CLLAS) 6201 University of Oregon Eugene, OR 97403-6201 (541)346-5286 [email protected] http://cllas.uoregon.edu July 2012 Pineros y Campesinos Unidos del Noroeste (PCUN) 300 Young Street Woodburn OR 97071 (503) 982-0243 www.pcun.org [email protected] Production Alice Evans Research Dissemination Specialist Center for Latino/a and Latin American Studies Proofing Eli Meyer, Assistant Director, CLLAS June Koehler, Research Assistant, CLLAS All photographs credited to PCUN unless otherwise noted The University of Oregon is an equal-opportunity, affirmative- action institution committed to cultural diversity and compliance with the Americans with Disabilities Act. This publication will be made available in accessible formats upon request. 750 CopieS 2 The Story of PCUN and the Farmworker Movement in Oregon Child in the field, 1995. -

Guide to Chicano Vertical Files

University of Texas at El Paso ScholarWorks@UTEP Finding Aids Special Collections Department 2020 Guide to Chicano Vertical Files UTEP Special Collections Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.utep.edu/finding_aid This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Collections Department at ScholarWorks@UTEP. It has been accepted for inclusion in Finding Aids by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UTEP. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Guide to Chicano vertical files Circa 1960s – 1980s April 28, 2020 Primarily collected by the Chicano Services section of the UTEP Library. Citation: Chicano vertical files, C.L. Sonnichsen Special Collections Department. The University of Texas at El Paso Library. C.L. Sonnichsen Special Collections Department University of Texas at El Paso Historical Sketch As part of its mission, the Chicano Services section of the UTEP Library collected materials for its vertical files during the 1970s and 1980s. Series Description or Arrangement These files are arranged alphabetically in three categories: topic or organization; individuals; and periodicals. Scope and Content Notes The Chicano vertical files date circa 1960s – 1980s and contain clippings, publications, periodicals, and other materials. These files help document Chicano history and culture, particularly in El Paso, other parts of Texas, and California. Provenance Statement Primarily collected by the Chicano Services section of the UTEP Library. Restrictions No rights to publications. Literary Rights Statement Permission to publish material from these files must be obtained from the C. L. Sonnichsen Special Collections Department, the University of Texas at El Paso Library. Citation should read, Chicano vertical files, C. -

File Under: Post-Mexico

File under: Post-Mexico Josh Kun Café Tacuba, VALE CALLAMPA (MCA, 2003) Café Tacuba, CUATRO CAMINOS (MCA, 2003) Jaguares, EL PRIMER INSTINTO (BMG, 2002) Jumbo, TELEPARQUE (BMG, 2003) El Gran Silencio, SUPER RIDDIM INTERNACIONAL, VOL. 1 (EMI Latin, 2003) Nortec Collective, THE TIJUANA SESSIONS, VOL. 1 (Palm, 2002) Various artists, MANOS ARRIBA! (Bungalow, 2003) Murcof, MARTES (Static, 2002) When the transnationalization of the economy and the culture situates us at the crossroads of multiple traditions and cultures, to limit our options to dependence or nationalism, modernization or local traditionality, is to simplify the actual dilemmas of our history. —Néstor García Canclini The video for one of Café Tacuba’s recent singles, “Déjate Caer,” opens with the band’s lead singer Rubén Albarrán leaning backwards over a panorama of Mexico City, his face cloaked in a black rooster mask. You can’t tell if he’s falling or flying or just teetering there, floating high above the chaotic metropolis that first gave birth to the band back in the late 1980s. The shot offers a near-perfect metaphor for the music that Tacuba has been making ever since—complex and style-swapping rock that, while rooted in the daily hustle and manic cultural collisions of Mexico City life, has always flown above its traffic jams and plazas into a worldly sky with no national limits. This inside-outside tug of war is even present in the song itself. Tacuba may make “Déjate Caer” their own, and with help from the video may give it a distinctly chilango slant, but this soundtrack to a new vision of Mexico City Aztlán 29:1 Spring 2004 © University of California Regents 271 Kun originally comes not from Mexico but from Chile and the Chilean band Los Tres. -

University of California, Berkeley. Chicano Studies Program Records, 1961-1996, Bulk 1969-1980

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt087031sh No online items Finding Aid to the University of California, Berkeley. Chicano Studies Program Records, 1961-1996, bulk 1969-1980 Finding Aid written by Finding Aid written by Janice Otani The Ethnic Studies Library 30 Stephens Hall #2360 University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California, 94720-2360 Phone: (510) 643-1234 Fax: (510) 643-8433 Email: [email protected] URL: http://eslibrary.berkeley.edu © 2007 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid to the University of CS ARC 2009/1 1 California, Berkeley. Chicano Studies Program Records, 19... Finding Aid to the University of California, Berkeley. Chicano Studies Program Records, 1961-1996, bulk 1969-1980 Collection Number: CS ARC 2009/1 The Ethnic Studies Library University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California Finding Aid Written By: Finding Aid written by Janice Otani Date Completed: October 2009 © 2009 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Collection Summary Collection Title: University of California, Berkeley. Chicano Studies Program records Date (inclusive): 1961-1996, Date (bulk): bulk 1969-1980 Collection Number: CS ARC 2009/1 Creators: University of California, Berkeley. Chicano Studies Program. Extent: Number of containers: 17 cartonsLinear feet: 21.25 Repository: University of California, Berkeley. Ethnic Studies Library 30 Stephens Hall #2360 University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California, 94720-2360 Phone: (510) 643-1234 Fax: (510) 643-8433 Email: [email protected] URL: http://eslibrary.berkeley.edu Abstract: The Chicano Studies Program records, 1961-1996 (bulk 1968-1980), provide materials relating to the formation of the program as a result of the Third World Strike student demands in 1969. -

San José Studies, Spring 1994

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks San José Studies, 1990s San José Studies Spring 1994 San José Studies, Spring 1994 San José State University Foundation Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/sanjosestudies_90s Part of the Chicana/o Studies Commons Recommended Citation San José State University Foundation, "San José Studies, Spring 1994" (1994). San José Studies, 1990s. 14. https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/sanjosestudies_90s/14 This Journal is brought to you for free and open access by the San José Studies at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in San José Studies, 1990s by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Studied Sfi^coxl In Memory of Cesar Chavez 1927-1993 Volume 20, Number 2 Spring 1994 $10.00 Volume XX, Number 2 Spring, 1994 EDITORS John Engell, English, San Jose State University D. Mesher, English, San Jose State University EMERITUS EDITOR Fauneil J. Rinn, Political Science, San Jose State University ASSOCIATE EDITORS Susan Shillinglaw, English, San Jose State University William Wiegand, Emeritus, Creative Writing, San Francisco State Kirby Wilkins, English, Cabril/o College EDITORIAL BOARD Garland E. Allen, Biology, Washington University Judith P. Breen, English, San Francisco State University Robert Casillo, English, University ofMiami , Coral Gables Richard Flanagan, Creative Writing, Babson College Barbara Charlesworth Gelpi, English, Stanford University Robert C. Gordon, English and Humanities, San Jose State University Richard E. Keady, Religious Studies, San Jose State University Jack Kurzweil, Electrical Engineering, San Jose State University Hank Lazer, English, University ofAlabama Lela A. Llorens, Occupational Therapy, San Jose State University Lois Palken Rudnik, American Studies, University ofMassachusetts, Boston Richard A.