I Can't Get Excited for a Child, Ritsuka

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Protoculture Addicts

PA #88 // CONTENTS PA A N I M E N E W S N E T W O R K ' S ANIME VOICES 4 Letter From The Publisher PROTOCULTURE¯:paKu]-PROTOCULTURE ADDICTS 5 Page 5 Editorial Issue #88 (Summer 2006) 6 Contributors Spotlight SPOTLIGHTS 98 Letters 25 BASILISK NEWS Overview Character Profiles 8 Anime Releases (R1 DVDs) Story Primer 10 Related Products Releases Shinobi: The live-action movie 12 Manga Releases By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier 17 Anime & Manga News 32 URUSEI YATSURA An interview with Robert Woodhead MANGA PREVIEW An Introduction By Zac Bertschy & Therron Martin 53 ES: Eternal Sabbath 35 VIZ MEDIA ANIME WORLD An interview with Alvin Lu By Zac Bertschy 73 Convention Guide 78 Interview ANIME STORIES Hitoshi Ariga 80 Making The Band 55 BEWITCHED AGNES 10 Tips from Full Moon on Becoming a Popstar Okusama Wa Maho Shoujo 82 Fantasia Genre Film Festival By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier Sample fileKamikaze Girls 58 BLOOD + The Taste Of Tea By Miyako Matsuda & C. Macdonald 84 The Modern Japanese Music Database Part 35: Home Page 19: Triceratops 60 ELEMENTAL GELADE By Miyako Matsuda REVIEWS 63 GALLERY FAKE 86 Books Howl’s Moving Castle Novel By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier Le Guide Phénix Du Manga 65 GUN SWORD Love Hina, Novel Vol. 1 By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier 87 Live-Action Lorelei 67 KAMICHU! 88 Manga Kamisama Wa Chugakusei 90 Related Products By Miyako Matsuda CD Soundtracks 69 TIDELINE BLUE Otaku Unite! By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier 91 Anime More on: www.protoculture-mag.com & www.animenewsnetwork.com 3 ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ LETTER FROM THE PUBLISHER A N I M E N E W S N E T W O R K ' S PROTOCULTUREPROTOCULTURE¯:paKu]- ADDICTS Over seven years of writing and editing anime reviews, I’ve put a lot of thought into what a Issue #88 (Summer 2006) review should be and should do, as well as what is shouldn’t be and shouldn’t do. -

Aachi Wa Ssipak Afro Samurai Afro Samurai Resurrection Air Air Gear

1001 Nights Burn Up! Excess Dragon Ball Z Movies 3 Busou Renkin Druaga no Tou: the Aegis of Uruk Byousoku 5 Centimeter Druaga no Tou: the Sword of Uruk AA! Megami-sama (2005) Durarara!! Aachi wa Ssipak Dwaejiui Wang Afro Samurai C Afro Samurai Resurrection Canaan Air Card Captor Sakura Edens Bowy Air Gear Casshern Sins El Cazador de la Bruja Akira Chaos;Head Elfen Lied Angel Beats! Chihayafuru Erementar Gerad Animatrix, The Chii's Sweet Home Evangelion Ano Natsu de Matteru Chii's Sweet Home: Atarashii Evangelion Shin Gekijouban: Ha Ao no Exorcist O'uchi Evangelion Shin Gekijouban: Jo Appleseed +(2004) Chobits Appleseed Saga Ex Machina Choujuushin Gravion Argento Soma Choujuushin Gravion Zwei Fate/Stay Night Aria the Animation Chrno Crusade Fate/Stay Night: Unlimited Blade Asobi ni Iku yo! +Ova Chuunibyou demo Koi ga Shitai! Works Ayakashi: Samurai Horror Tales Clannad Figure 17: Tsubasa & Hikaru Azumanga Daioh Clannad After Story Final Fantasy Claymore Final Fantasy Unlimited Code Geass Hangyaku no Lelouch Final Fantasy VII: Advent Children B Gata H Kei Code Geass Hangyaku no Lelouch Final Fantasy: The Spirits Within Baccano! R2 Freedom Baka to Test to Shoukanjuu Colorful Fruits Basket Bakemonogatari Cossette no Shouzou Full Metal Panic! Bakuman. Cowboy Bebop Full Metal Panic? Fumoffu + TSR Bakumatsu Kikansetsu Coyote Ragtime Show Furi Kuri Irohanihoheto Cyber City Oedo 808 Fushigi Yuugi Bakuretsu Tenshi +Ova Bamboo Blade Bartender D.Gray-man Gad Guard Basilisk: Kouga Ninpou Chou D.N. Angel Gakuen Mokushiroku: High School Beck Dance in -

JAPAN CUTS: Festival of New Japanese Film Announces Full Slate of NY Premieres

Media Contacts: Emma Myers, [email protected], 917-499-3339 Shannon Jowett, [email protected], 212-715-1205 Asako Sugiyama, [email protected], 212-715-1249 JAPAN CUTS: Festival of New Japanese Film Announces Full Slate of NY Premieres Dynamic 10th Edition Bursting with Nearly 30 Features, Over 20 Shorts, Special Sections, Industry Panel and Unprecedented Number of Special Guests July 14-24, 2016, at Japan Society "No other film showcase on Earth can compete with its culture-specific authority—or the quality of its titles." –Time Out New York “[A] cinematic cornucopia.” "Interest clearly lies with the idiosyncratic, the eccentric, the experimental and the weird, a taste that Japan rewards as richly as any country, even the United States." –The New York Times “JAPAN CUTS stands apart from film festivals that pander to contemporary trends, encouraging attendees to revisit the past through an eclectic slate of both new and repertory titles.” –The Village Voice New York, NY — JAPAN CUTS, North America’s largest festival of new Japanese film, returns for its 10th anniversary edition July 14-24, offering eleven days of impossible-to- see-anywhere-else screenings of the best new movies made in and around Japan, with special guest filmmakers and stars, post-screening Q&As, parties, giveaways and much more. This year’s expansive and eclectic slate of never before seen in NYC titles boasts 29 features (1 World Premiere, 1 International, 14 North American, 2 U.S., 6 New York, 1 NYC, and 1 Special Sneak Preview), 21 shorts (4 International Premieres, 9 North American, 1 U.S., 1 East Coast, 6 New York, plus a World Premiere of approximately 12 works produced in our Animation Film Workshop), and over 20 special guests—the most in the festival’s history. -

Protoculture Addicts Is ©1987-2006 by Protoculture • the REVIEWS Copyrights and Trademarks Mentioned Herein Are the Property of LIVE-ACTION

Sample file CONTENTS 3 ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ P r o t o c u l t u r e A d d i c t s # 8 7 December 2005 / January 2006. Published by Protoculture, P.O. Box 1433, Station B, Montreal, Qc, Canada, H3B 3L2. ANIME VOICES Letter From The Publisher ......................................................................................................... 4 E d i t o r i a l S t a f f Page Five Editorial ................................................................................................................... 5 [CM] – Publisher Christopher Macdonald Contributor Spotlight & Staff Lowlight ......................................................................................... 6 [CJP] – Editor-in-chief Claude J. Pelletier Letters ................................................................................................................................... 74 [email protected] Miyako Matsuda [MM] – Contributing Editor / Translator Julia Struthers-Jobin – Editor NEWS Bamboo Dong [BD] – Associate-Editor ANIME RELEASES (R1 DVDs) ...................................................................................................... 7 Jonathan Mays [JM] – Associate-Editor ANIME-RELATED PRODUCTS RELEASES (UMDs, CDs, Live-Action DVDs, Artbooks, Novels) .................. 9 C o n t r i b u t o r s MANGA RELEASES .................................................................................................................. 10 Zac Bertschy [ZB], Sean Broestl [SB], Robert Chase [RC], ANIME & MANGA NEWS: North -

Copy of Anime Licensing Information

Title Owner Rating Length ANN .hack//G.U. Trilogy Bandai 13UP Movie 7.58655 .hack//Legend of the Twilight Bandai 13UP 12 ep. 6.43177 .hack//ROOTS Bandai 13UP 26 ep. 6.60439 .hack//SIGN Bandai 13UP 26 ep. 6.9994 0091 Funimation TVMA 10 Tokyo Warriors MediaBlasters 13UP 6 ep. 5.03647 2009 Lost Memories ADV R 2009 Lost Memories/Yesterday ADV R 3 x 3 Eyes Geneon 16UP 801 TTS Airbats ADV 15UP A Tree of Palme ADV TV14 Movie 6.72217 Abarashi Family ADV MA AD Police (TV) ADV 15UP AD Police Files Animeigo 17UP Adventures of the MiniGoddess Geneon 13UP 48 ep/7min each 6.48196 Afro Samurai Funimation TVMA Afro Samurai: Resurrection Funimation TVMA Agent Aika Central Park Media 16UP Ah! My Buddha MediaBlasters 13UP 13 ep. 6.28279 Ah! My Goddess Geneon 13UP 5 ep. 7.52072 Ah! My Goddess MediaBlasters 13UP 26 ep. 7.58773 Ah! My Goddess 2: Flights of Fancy Funimation TVPG 24 ep. 7.76708 Ai Yori Aoshi Geneon 13UP 24 ep. 7.25091 Ai Yori Aoshi ~Enishi~ Geneon 13UP 13 ep. 7.14424 Aika R16 Virgin Mission Bandai 16UP Air Funimation 14UP Movie 7.4069 Air Funimation TV14 13 ep. 7.99849 Air Gear Funimation TVMA Akira Geneon R Alien Nine Central Park Media 13UP 4 ep. 6.85277 All Purpose Cultural Cat Girl Nuku Nuku Dash! ADV 15UP All Purpose Cultural Cat Girl Nuku Nuku TV ADV 12UP 14 ep. 6.23837 Amon Saga Manga Video NA Angel Links Bandai 13UP 13 ep. 5.91024 Angel Sanctuary Central Park Media 16UP Angel Tales Bandai 13UP 14 ep. -

Seven Seas April 2017 Catalog Final 8.16.16.Indd

Seven Seas April 2017 Akuma no Riddle: Riddle Story of Devil, vol. 5 Story by Yun Kouga Art by Sunao Minakata From the bestselling creator of Loveless comes an all-new manga series From the famed creator of Loveless, Yun Kouga, comes her newest work: Akuma no Riddle: Riddle Story of Devil. A completely fresh and edgy take on the yuri genre, Akuma no Riddle: Riddle Story of Devil is a tale of love that blossoms on the battlefield, in the midst of a dangerous cat-and-mouse game between assassins. Akuma no Riddle: Riddle Story of Devil has been adapted into a hit anime series, which was streamed by Funimation and was released on home video in December 2015. Each volume contains kinetic artwork, brimming with action and (cover in development) drama, and includes color inserts. MANGA t Myojo Academy, an elite all-girls boarding school, the Class Trade Paperback ABlack is comprised of thirteen students, twelve of whom are ISBN: 978-1-626923-38-6 assassins. Their prey is the thirteenth student, Haru Ichinose, an $12.99/US | $14.99/CAN upbeat girl who vows to survive school and graduate unharmed! 5” x 7.125”/ 180 pages Enter Tokaku Azuma, a cold-blooded killer who transfers from Age: Teen (13+) another school to kill Haru. On Sale: April 4, 2017 What should have been a routine hit turns into a far more MARKETING PLANS: complicated affair as Tokaku is unable to pull the trigger on Haru. As • Promotion at gomanga.com • Promotion on Twitter, Tumblr, Tokaku copes with her strange, budding feelings, will she decide to and Facebook protect Haru’s life from the other assassins or to end it? Yun Kouga is best known as the creator of Loveless and is a well- known doujinshi author and artist. -

1 07 Ghost 2 11 Eyes 3 801 TTS Airbat 4 Abenobashi Mahou

1 07 Ghost 37 Amnesia (Movie) 2 11 Eyes 38 Angel Beats 3 801 TTS Airbat 39 Angel Sanctuary 4 Abenobashi Mahou Shoutengai 40 Angel's Feathers (Yaoi) 5 Abrazo de Primavera (Yaoi) 41 Antique Bakery 6 Accelerado (Hentai) 42 Ao no Exorcist 7 AD Police 43 Aoi Bungaku 8 Afro Samirai Resurrection 44 Aoi Hana 9 Afro Samurai 45 Appleseed 10 After the School in the Teacher's Lounge 46 Aquariam Age 11 Agent Aika 47 Araiso (Yaoi) 12 Ah! Megamisama 48 Arakawa Under The Bridge 13 Ah! Megamisama (Movie) 49 Arashi no Ato (Manga - Yaoi) 14 Ah! Megamisama (OVA) 50 Argento Soma 15 Ai no Kusabi (Yaoi) 51 Aria -Arietta- (OVA) 16 Ai Yori Aoshi 52 Aria The Animation 17 Ai Yori Aoshi - Enishi - 53 Aria The Navegation 18 Aika R-16 54 Aria The Origination 19 Aika Zero 55 Aria The Scarlet Ammo 20 Air 56 Armitage III 21 Air (OVA) 57 Asterix El Galo (Movie) 22 Air Gear 58 Asterix y Cleopatra (Movie) 23 Air Tonelico (Movie) 59 Asterix y La Sorpresa del Cesar (Movie) 24 Aiso Tsukash (Manga - Yaoi) 60 Asterix y las 12 Pruebas (Movie) 25 Aitsu no Daihonmei (Manga - Yaoi) 61 Asterix y Los Bretones (Movie) 26 Aitsu no Heart Uihi wo Tsukeru (Manga - Yaoi) 62 Asterix y Los Vikingos (Movie) 27 Akane Maniac 63 Asu no Yoichi 28 Akane-Iro ni Somaru Saka 64 Asura Criyn' 29 Akira 65 Asura Criyn' II 30 Akuma no Himitsu (Manga - Yaoi) 66 Asuza 31 Amaenaideyo 67 Avatar Libro 1 Agua 32 Amaenaideyo - Especial - (OVA) 68 Avatar Libro 2 Tierra 33 Amaenaideyo Katsu 69 Avatar Libro 3 Fuego 34 Amagami SS 70 Avenger 35 Amame Pecaminosamente (Manga - Yaoi) 71 Ayakashi Japanese Classic Horror -

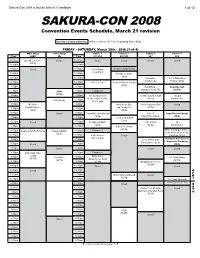

Sakura-Con 2008 Schedule, March 21 Revision 1 of 12

Sakura-Con 2008 schedule, March 21 revision 1 of 12 SAKURA-CON 2008 FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 28th - 29th (2 of 4) FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 28th - 29th (3 of 4) FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 28th - 29th (4 of 4) Panels 5 Autographs Console Arcade Music Gaming Workshop 1 Workshop 2 Karaoke Main Anime Theater Classic Anime Theater Live-Action Theater Anime Music Video FUNimation Theater Omake Anime Theater Fansub Theater Miniatures Gaming Tabletop Gaming Roleplaying Gaming Collectible Card Youth Matsuri Convention Events Schedule, March 21 revision 3A 4B 615-617 Lvl 6 West Lobby Time 206 205 2A Time Time 4C-2 4C-1 4C-3 Theater: 4C-4 Time 3B 2B 310 304 305 Time 306 Gaming: 307-308 211 Time Closed Closed Closed Closed 7:00am Closed Closed Closed 7:00am 7:00am Closed Closed Closed Closed 7:00am Closed Closed Closed Closed Closed 7:00am Closed Closed Closed 7:00am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am Bold text in a heavy outlined box indicates revisions to the Pocket Programming Guide schedule. 8:00am Karaoke setup 8:00am 8:00am The Melancholy of Voltron 1-4 Train Man: Densha Otoko 8:00am Tenchi Muyo GXP 1-3 Shana 1-4 Kirarin Revolution 1-5 8:00am 8:00am 8:30am 8:30am 8:30am Haruhi Suzumiya 1-4 (SC-PG V, dub) (SC-PG D) 8:30am (SC-14 VSD, dub) (SC-PG V, dub) (SC-G) 8:30am 8:30am FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 28th - 29th (1 of 4) (SC-PG SD, dub) 9:00am 9:00am 9:00am 9:00am (9:15) 9:00am 9:00am Karaoke AMV Showcase Fruits Basket 1-3 Pokémon Trading Figure Pirates of the Cursed Seas: Main Stage Turbo Stage Panels 1 Panels 2 Panels 3 Panels 4 Open Mic -

Seven Seas Titles ● September 2015 - December 2015

Macmillan Publishers MPS Distribution Center, 16365 James Madison Highway, Gordonsville, VA 22942-8501 ACCOUNT NO. WHSE ORDER DATE P.O. NO. QTY TO PLACE AN ORDER CALL: 1 (888) 330-8477 OR FAX: 1 (800) 672-2054 DATE DEPT.NO. SALESREP TERRITORY NO. BUYER SHIP VIA BILL TO: SHIP TO: SPECIAL INSTRUCTIONS: Please circle the type of bookseller you are. Independent Retailer: use promo code T019 Retail Distribution Center: use promo code T420DC Wholesaler/Jobber: use promo code T422WH ZIP: ZIP: FIFTH AVENUE ORDER FORM ● SEVEN SEAS TITLES ● SEPTEMBER 2015 - DECEMBER 2015 SEPT ______ 9781626921634 1626921636 Alice in the Country of Clover: Black 13.99 USA / 15.99 TP MANGA Lizard and Bitter Taste 2 • QuinRose / CAN Minamoto, Ichimi ______ 9781626921924 162692192X The Ancient Magus' Bride Vol. 2 • 12.99 USA / 14.99 TP MANGA Yamazaki, Kore CAN ______ 9781626921511 1626921512 Dance in the Vampire Bund Omnibus 19.99 USA / 22.99 TP MANGA 6 (The Memories of Sledgehammer CAN Vol. 1-3) • Tamaki, Nozomu ______ 9781626921726 1626921725 D-Frag! Vol. 6 • Haruno, Tomoya 12.99 USA / 14.99 TP MANGA CAN ______ 9781626921733 1626921733 Dictatorial Grimoire: The Complete 20.99 USA / 23.99 TP MANGA Collection • Kanou, Ayumi CAN ______ 9781626921986 1626921989 Freezing Vol. 3-4 • Lim, Dall-Young / 19.99 USA / 22.99 TP MANGA Kim, Kwang-Hyun CAN ______ 9781626921740 1626921741 Haganai: I Don't Have Many Friends 12.99 USA / 14.99 TP MANGA Vol. 12 • Hirasaka, Yomi / Itachi CAN ______ 9781626921610 162692161X Non Non Biyori Vol. 2 • Atto 12.99 USA / 14.99 TP MANGA CAN ______ 9781626921832 1626921830 Servamp Vol. -

Seven Seas April 2016 Akuma No Riddle: Riddle Story of Devil, Vol

Seven Seas April 2016 Akuma no Riddle: Riddle Story of Devil, vol. 3 Story by Yun Kouga Art by Sunao Minakata From the bestselling creator of Loveless comes an all-new manga series From the famed creator of Loveless, Yun Kouga, comes her newest work: Akuma no Riddle: Riddle Story of Devil. A completely fresh and edgy take on the yuri genre, Akuma no Riddle: Riddle Story of Devil is a tale of love that blossoms on the battlefield, in the midst of a dangerous cat-and-mouse game between assassins. Akuma no Riddle: Riddle Story of Devil has been adapted into a hit anime series, which was streamed by FUNimation and will be released on home video in 2015. Each volume contains kinetic artwork, brimming with action and (cover in development) drama, and includes color inserts. MANGA t Myojo Academy, an elite all-girls boarding school, the Class Trade Paperback ABlack is comprised of thirteen students, twelve of whom are ISBN: 978-1-626922-54-9 assassins. Their prey is the thirteenth student, Haru Ichinose, an $12.99/US | $14.99/CAN upbeat girl who vows to survive school and graduate unharmed! 5” x 7.125”/ 164 pages Enter Tokaku Azuma, a cold-blooded killer who transfers from Age: Teen (13+) another school to kill Haru. On Sale: April 5, 2016 What should have been a routine hit turns into a far more MARKETING PLANS: complicated affair as Tokaku is unable to pull the trigger on Haru. As • Promotion at gomanga.com • Promotion on Twitter, Tumblr, Tokaku copes with her strange, budding feelings, will she decide to and Facebook protect Haru’s life from the other assassins or to end it? Yun Kouga is best known as the creator of Loveless, and is a well- known doujinshi author and artist. -

Graphic Novel Series

August 2019 Title Bib # Publisher .Hack 17006296 .Hack//g.u.+ 1889995x 0/6 21707212 07-ghost 2342980x 11th cat 10683483 A devil and her love song 22127732 A.I. I love you 21707200 Adolf 10294211 Adventure time : original series 24307713 Adventures of Tintin : 3 in 1 11411879 Afterschool charisma 24182783 Age of bronz 17159775 Akira 20503891 Kodansha Comics Akira 15493519 Dark Horse Alice 19th 10680214 Alice in the country of clover 24154635 Tokyopop Alice in the country of hearts 20531321 Tokyopop amazing Spider-Man 16124364 amazing Spider-Man : world-wide 24571969 American vampire 24399267 Amulet 2019433x ancient magus' bride 24483916 Andel diary 16941949 Angel catbird 25080556 Anonymous noise 25308440 Arata 24110814 Ariol 23898604 Arisa 21280265 Assassination classroom 24335125 Astonishing X-Men 10698887 Astonishing X-Men 2576200x Astro boy 19459919 Attack on Titan 22986819 Attack on Titan before the fall 24295942 Attack on Titan Junior High 23218071 Attack on Titan no regrets 24015970 Avengers K. Avengers vs. Ultron 25100877 B.B. explosion 15777613 Babymouse 17387528 Bakuman 21677219 Banana fish 13362161 Viz Basara 18663680 Batgirl 23245669 Batman 22776230 Batman & Robin 22442881 DC comics Batman and Robin 22189166 DC comics Batman black & white 25061677 Batman Eternal 2456042x Batman, Detective Comics 22801169 Batman/Superman 2403583x Berserk 20304274 Black bird 21420233 Black butler 20531163 Black cat 1734685x Black clover 24869041 Black jack 19705013 Black lagoon 23887680 Black Panther 24920034 Bleach 26200065 3 in 1 edition Bleach 17337987 Blue exorcist 21906361 Bokurano = ours 22461048 Bone 19760176 Books of magic 26206602 Boruto 25057595 Boys over flowers =Hana yori dango 15315241 Bride's story 21664250 Btoom 24012014 Buso Renkin 16871662 Cardcaptor Sakura 22121985 1st ed., Omnibus ed. -

Eksistensi Fujoshi Di Kalangan Pecinta Kebudayaan Jepang

EKSISTENSI FUJOSHI DI KALANGAN PECINTA KEBUDAYAAN JEPANG (Studi Etnografi terhadap Wanita Penyuka Fiksi Homoseksual di Kota Medan, Sumatera Utara) Skripsi Diajukan Guna Memenuhi Salah Satu Syarat Untuk Memperoleh Gelar Sarjana Ilmu Sosial dalam Bidang Ilmu Antropologi Oleh: IZMI WARDAH AMMAR NIM 130905011 DEPARTEMEN ANTROPOLOGI SOSIAL FAKULTAS ILMU SOSIAL DAN ILMU POLITIK UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA MEDAN 2018 Universitas Sumatera Utara UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA FAKULTAS ILMU SOSIAL DAN ILMU POLITIK PERNYATAAN ORISINALITAS EKSISTENSI FUJOSHI DI KALANGAN PECINTA KEBUDAYAAN JEPANG (Studi Etnografi terhadap Wanita Penyuka Fiksi Homoseksual di Kota Medan, Sumatera Utara) S K R I P S I Dengan ini saya menyatakan bahwa dalam skripsi ini tidak terdapat karya yang pernah diajukan untuk memperoleh gelar keserjanaan di suatu perguruan tinggi, dan sepanjang pengetahuan saya juga tidak terdapat karya atau pendapat yang pernah ditulis atau diterbitkan oleh orang lain, kecuali yang secara tertulis diacu dalam naskah ini dan disebut dalam daftar pustaka. Apabila di kemudian hari terbukti lain atau tidak seperti yang saya nyatakan di sini, saya bersedia diproses secara hukum dan siap menanggalkan gelar kesarjanaan saya. Medan, 07 Desember 2017 Penulis Izmi Wardah Ammar Universitas Sumatera Utara ABSTRAK Izmi Wardah Ammar, 130905011 (2017). Skipsi ini berjudul EKSISTENSI FUJOSHI DI KALANGAN PECINTA KEBUDAYAAN JEPANG (Studi Etnografi terhadap Wanita Penyuka Fiksi Homoseksual di Kota Medan, Sumatera Utara). Skripsi ini terdiri dari lima bab, 145 halaman, 20 gambar, dan dua tabel. Penelitian ini membahas mengenai sekelompok wanita penggemar Yaoi atau fiksi homoseksual yang lebih dikenal dengan fujoshi. Yaoi adalah sebuah genre asal Jepang dan biasanya disebarkan dalam media anime dan manga. Penelitian ini berlokasi di kota Medan sebagai kota ketiga terbesar di Indonesia dan kota terbesar di pulau Sumatera.