A Comparison of Reduplication in Limonese Creole and Akan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Limón Patwa: a Perceptual Study to Measure Language Attitudes Toward Speakers of Patwa in Costa Rica

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Linguistics Linguistics 2019 LIMÓN PATWA: A PERCEPTUAL STUDY TO MEASURE LANGUAGE ATTITUDES TOWARD SPEAKERS OF PATWA IN COSTA RICA Robert Bell University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/etd.2019.352 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Bell, Robert, "LIMÓN PATWA: A PERCEPTUAL STUDY TO MEASURE LANGUAGE ATTITUDES TOWARD SPEAKERS OF PATWA IN COSTA RICA" (2019). Theses and Dissertations--Linguistics. 32. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/ltt_etds/32 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Linguistics at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Linguistics by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

SPCL Program 2009 Graphic 8 Jan 09

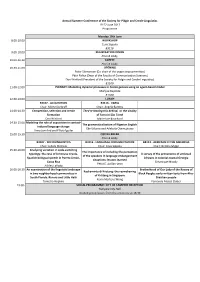

program version (8 JAN 09) 2009 SOCIETY FOR PIDGIN AND CREOLE LINGUISTICS CONFERENCE PROGRAM SAN FRANCISCO , CA, USA FRIDAY & SATURDAY 9-10 JANUARY 2009 rd Meeting in conjunction with the 83 Annual Meeting of the Linguistic Society of America Venue: Hilton San Francisco 333 O'Farrell Street, San Francisco, California 94102 Tel: 1-415-771-1400 Fax: 1-415-771-6807 http://www1.hilton.com/en_US/hi/hotel/SFOFHHH-Hilton-San-Francisco-California/index.do General info: http://www.mona.uwi.edu/dllp/spcl/Conferences.html or http://www.lsadc.org/ Contact: Rocky R. Meade Sessions start at 8:45am [email protected] Please arrive a few minutes early. Tel (876) 815-4094 FRIDAY MORNING, 9 January 2009 (8:45 – 12:00) Session 1 [LSA 88] ROOM : UNION SQUARE 23 : 8:45 Conference Opening Remarks Arthur Spears - President SYNTAX /G RAMMATICALIZATION Chair: Arthur Spears (City University of New York) 9:00 Malcolm Finney (California State University): Syntactic Dependency and Instrumental Constructions in Krio: Distinguishing Serial Verb Constructions from Overt or Covert Coordinate Structures 9:30 Danny Adone (University of Cologne): Grammaticalisation and Creolisation: The Case of Ngukurr Kriol OSTER RESENTATIONS CAN BE VIEWED IN Grand Ballroom A 10:00- Break P P [LSA 89] 10:30 [LSA 90] ROOM : UNION SQUARE 23 [LSA 91] ROOM : UNION SQUARE 24 Session 2A Session 2B AFRICAN AMERICAN ENGLISH PHONOLOGY Chair: Armin Schwegler (University of California, Irvine) Chair: Rocky R. Meade (University of the West Indies, Mona) 10:30 Arthur Spears (City University -

“Islands – in – Between” Conference: Language, Literature, & Culture of the Eastern Caribbean St. George's, Grenada 3-5 November 2011

“Islands – in – Between” Conference November 3-5, 2011 Grenada 14th Annual “islands – in – Between” Conference: Language, Literature, & Culture of the Eastern Caribbean St. George’s, Grenada 3-5 November 2011 ABSTRACTS St. George’s, Gre nada Photo Provided by Angel Rivera 1 “Islands – in – Between” Conference November 3-5, 2011 Grenada Abstracts Compiled by Marisol Joseph (UPR – Río Piedras ) Alim A. Hosein University of Guyana GUYANESE PHONOLOGY Guyanese Creole English (hereafter GY) has long been cited as one of the Caribbean creoles which is decreolising - that is, gradually losing its original creole features since it is in contact with another influential language (in this case, English). This paper looks for the possible effects of decreolisation n one linguistic system, Phonology, in current Guyanese language use. Is a change towards more English-like pronunciation to be seen in GY? Or, given the social and cultural developments that have taken place in the country since decreolisation was first proposed half a century ago, has the language stabilised and consolidated in its creole elements? These questions are answered through phonological and sociolinguistic examination of samples of pronunciation taken from the natural speech of Guyanese from various locations, walks of life and in different social situations. The analysis of phonological variables (e.g. vowel shift, allophonic variations, phonological processes) provides the basis for the sociolinguistic examination to identify similarities, differences and overlaps in pronunciation across different social contexts (e.g. formal and informal situations) where different levels of speech would normally be expected. Through the examination of conformity to and deviation from expected norms of pronunciation in such contexts, conclusions about the current state of GY in relation to the kinds of changes implied by decreolisation are made. -

Bilingual Rhotics in Two Island Communities of the Archipelago of San Andres, Colombia

LANGUAGE CONTACT AND CONVERGING PATHS OF VARIATION: BILINGUAL RHOTICS IN TWO ISLAND COMMUNITIES OF THE ARCHIPELAGO OF SAN ANDRES, COLOMBIA By FALCON D. RESTREPO-RAMOS A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2019 © 2019 Falcon D. Restrepo-Ramos Jezu, Ufam Tobie! ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to start by thanking my dissertation committee for believing in this project and for their invaluable support throughout all stages. My mentor, Dr. Aaron, for her insightful guidance and knowleadgeable comments and suggestions, which assured the successful completion of this dissertation. I hope I can carry on your example. Dr. Gillian Lord for being a beacon of light and hope through all these years. Dr. Valdés-Kroff for always looking forward to the success of this work. Your guidance will have a lasting impact on my career. Dr. Essegbey for being a voice of reason and being readily available for help. It goes without saying that I am greatly indebted to all the spectacular faculty, staff, and colleagues at the Department of Spanish and Portugues Studies for all their support and consideration. Five years ago, I arrived at the University of Florida with many dreams and barely enough to support myself, but I was welcomed with a smile and the opportunity to become part of the Department. It was there that I had a sense of the great things that were coming in my future. I look back and I can’t thank you enough Prof. -

New Cambridge History of the English Language

New Cambridge History of the English Language Volume V: English in North America and the Caribbean Editors: Natalie Schilling (Georgetown), Derek Denis (Toronto), Raymond Hickey (Essen) I The United States 1. Language change and the history of American English (Walt Wolfram) 2. The dialectology of Anglo-American English (Natalie Schilling) 3. The roots and development of New England English (James N. Stanford) 4. The history of the Midland-Northern boundary (Matthew J. Gordon) 5. The spread of English westwards (Valerie Fridland and Tyler Kendall) 6. American English in the city (Barbara Johnstone) 7. English in the southern United States (Becky Childs and Paul E. Reed) 8. Contact forms of American English (Cristopher Font-Santiago and Joseph Salmons) African American English 9. The roots of African American English (Tracey L. Weldon) 10. The Great Migration and regional variation in the speech of African Americans (Charlie Farrington) 11. Urban African American English (Nicole Holliday) 12. A longitudinal panel survey of African American English (Patricia Cukor-Avila) Latinx English 13. Puerto Rican English in Puerto Rico and in the continental United States (Rosa E. Guzzardo Tamargo) 14. The English of Americans of Mexican and Central American heritage (Erik R. Thomas) II Canada 15. Anglophone settlement and the creation of Canadian English (Charles Boberg) NewCHEL Vol 5: English in North America and the Caribbean Page 2 of 2 16. The open-class lexis of Canadian English: History, structure, and social correlations (Stefan Dollinger) 17. Ontario English: Loyalists and beyond (Derek Denis, Bridget Jankowski and Sali A. Tagliamonte) 18. The Prairies and the West of Canada (Alex D’Arcy and Nicole Rosen) 19. -

The Influence of Spanish Lexicon on Limonese Creole: Negative Implications

Revista de Lenguas ModeRnas, N° 21, 2014 / 225-241 / ISSN: 1659-1933 The Influence of Spanish Lexicon on Limonese Creole: Negative Implications Ginneth Pizarro ChaCón Escuela de Literatura y Ciencias del Lenguaje Universidad Nacional (UNA) [email protected] Paula Fallas Domian Escuela de Literatura y Ciencias del Lenguaje Universidad Nacional (UNA) [email protected] Abstract After working in the construction of the railroad that communicates Li- món with San José, many Afro-Caribbean people who had arrived during the 1870’s, especially from Jamaica, stayed and established themselves in Limón. In the 20th century, some Costa Rican Spanish speakers star- ted to migrate to Limón; as a result, their Spanish language influenced Limonese Creole and made speakers start substituting some English lexicon, root morphemes, and word order for the Spanish one. As time has passed, more Costa Rican Spanish elements have been incorporated and mixed into the English Creole. In addition, many of the inhabitants of Limón who spoke Limonese Creole moved to San José and adopted Spanish. Depending on the event or situation, Limonese use either Costa Rican Spanish, Limonese Creole, or code-switch between both of them. The chief purpose of this research is to investigate and analyze the in- fluence of Costa Rican Spanish lexicon on Limonese Creole and how this English variety has been affected by its Costa Rican Spanish influence. Key words: Limonese Creole, Jamaican Creole, subordinate group, mi- gration, lexicon, code switching, diglossia Resumen Después de trabajar en la construcción del ferrocarril que comunica Li- món con San José, muchas personas afro-caribeñas que habían llegado sobre todo de Jamaica durante los años de la década que arranca en 1870, se quedaron y se establecieron en Limón. -

Framing and Understanding the Linguistic Situation Found in Limón, Costa Rica Through the Study of Language Attitudes

Revista de Filología y Lingüística de la Universidad de Costa Rica ISSN: 0377-628X ISSN: 2215-2628 [email protected] Universidad de Costa Rica Costa Rica Framing and Understanding the Linguistic Situation Found in Limón, Costa Rica Through the Study of Language Attitudes Aguilar-Sánchez, Jorge Framing and Understanding the Linguistic Situation Found in Limón, Costa Rica Through the Study of Language Attitudes Revista de Filología y Lingüística de la Universidad de Costa Rica, vol. 44, no. 2, 2018 Universidad de Costa Rica, Costa Rica Available in: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=33267713007 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15517/rfl.v44i2.34693 PDF generated from XML JATS4R by Redalyc Project academic non-profit, developed under the open access initiative Jorge Aguilar-Sánchez. Framing and Understanding the Linguistic Situation Found in Limón, Costa Ri... Lingüística Framing and Understanding the Linguistic Situation Found in Limón, Costa Rica rough the Study of Language Attitudes Enmarcando y comprendiendo la situación lingüística en Limón, provincia de Costa Rica a través del estudio de actitudes sobre la lengua Jorge Aguilar-Sánchez DOI: https://doi.org/10.15517/rfl.v44i2.34693 University of Dayton, Estados Unidos Redalyc: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa? [email protected] id=33267713007 Received: 07 December 2017 Accepted: 17 March 2018 Resumen: Limón, provincia de Costa Rica, presenta una inusual situación lingüística que ha sido abordada desde diferentes perspectivas. Los estudios sobre inglés limonense se encuentran dentro de los paradigmas de criollos ingleses, lingüística general, y antropología y sociología. Aunque no es única, la situación lingüística de Limón presenta retos para el diseño de investigación y para la recolección de datos debido a que dicha situación se caracteriza por la presencia de varias lenguas que cohabitan en la misma área. -

SPCL Program.Pdf

Annual Summer Conference of the Society for Pidgin and Creole Linguistics 19‐22 June 2017 Programme Monday 19th June 8.00‐10.00 WORKSHOP Eeva Sippola B3116 9.00‐10.00 REGISTRATION OPENS Pinni B lobby 10.00‐10.30 COFFEE Pinni B lobby 10.30‐11.00 OPENING Peter Slomanson (Co‐chair of the organising committee) Päivi Pahta (Dean of the Faculty of Communication Sciences) Don Winford (President of the Society for Pidgin and Creole Linguistics) B1100 11.00‐12.00 PLENARY: Modelling dynamic processes in Creole genesis using an agent‐based model Marlyse Baptista B1100 12.00‐14.00 LUNCH B3107 ‐ ACQUISITION B3116 ‐ VARIA Chair: Michel DeGraff Chair: Angela Bartens 14.00‐14.30 Competition, selection and creole They’re leaving this behind, or the vitality formation of Forro in São Tomé Don Winford Marie‐Eve Bouchard 14.30‐15.00 Modeling the role of acquisition in contact‐ The grammaticalization of Nigerian English induced language change Eke Uduma and Adebola Otemuyiuwa Anna Jon‐And and Elliot Aguilar 15.00‐15.30 COFFEE BREAK Pinni B lobby B3107 ‐ SOCIOLINGUISTICS B3116 ‐ LANGUAGE DOCUMENTATION B4113 ‐ AFRICANS IN THE AMERICAS Chair: Juhani Klemola Chair: Eeva Sippola Chair: Bettina Migge 15.30‐16.00 Analyzing variation in code‐switching The importance of including the perception typology: the case of Limonese Creole‐ A survey of the provenance of enslaved of the speakers in language endangerment Spanish bilingual speech in Puerto Limón, Africans in colonial coastal Georgia situations: lessons learned Costa Rica Simanique Moody Petra E. Avillan‐Leon -

Limon Creole Phrases: a Vehicle for Linguistic and Cultural Preservation1

Limon Creole Phrases: A Vehicle for Linguistic and Cultural Preservation1 (Frases de criollo limonense: vehículo para la conservación lingüística y cultural) Ginneth Pizarro Chacón2 Universidad Nacional, Costa Rica Damaris Cordero Badilla3 Universidad Nacional, Costa Rica ABSTRACT Phrases and idiomatic expressions used in everyday speech in Limon Cre- ole by a group of elderly people have been collected in the province of Li- mon, Costa Rica, to preserve those phrases as part of their legacy to future generations. Considering the age factor, the information was gathered by applying a questionnaire to 50 native speakers of Limon Creole. Recom- mendations are provided, based on the results of the study. RESUMEN Se recogen frases y expresiones idiomáticas del criollo limonense del habla cotidiana de un grupo de ancianos en la provincia de Limón, Costa Rica, con el fin de preservarlas como parte del patrimonio lingüístico regional. La información fue recolectada mediante un cuestionario a cincuenta infor- mantes del criollo limonense, considerando el factor etario. Con base en los resultados del estudio se plantean recomendaciones pertinentes. 1 Recibido: 28 de febrero de 2015; aceptado: 30 de agosto de 2016. 2 Escuela de Literatura y Ciencias del Lenguaje. Correo electrónico: [email protected] 3 Escuela de Literatura y Ciencias del Lenguaje. Correo electrónico: [email protected] LETRAS 58 (2015), ISSN 1409-424X; EISSN 2215-4094 91 Pizarro • Cordero LETRAS 58 (2015) Keywords: Limon Creole; idiomatic expressions; linguistic diversity; age factors Palabras clave: criollo limonense; expresiones idiomáticas; diversidad lin- güística; criterios etarios Introduction Phraseological units are a common feature of languages; these expressions become used and recognized as representative elements of a culture. -

Jamaican Patois - Wikipedia Page 1 of 14 Visted on 10/27/2020

Jamaican Patois - Wikipedia Page 1 of 14 Visted on 10/27/2020 Jamaican Patois Jamaican Patois Patwa, Jamiekan / Jamiekan Kriyuol[1], Jumiekan / Jumiekan Kryuol / Jumieka Taak / Jumieka taak / Jumiekan languij[2][3] Native to Jamaica, Panama, Costa Rica, Colombia (San Andrés y Providencia). Native speakers 3.2 million (2000–2001)[4] Language English creole family ◾ Atlantic ◾ Western ◾ Jamaican Patois Dialects Limonese Creole Bocas del Toro Creole Miskito Coast Creole San Andrés–Providencia Creole Official status Regulated by not regulated Language codes ISO 639-3 jam Glottolog jama1262 (http://glottolog.org/resource/languoid/id/jama1262) [5] Linguasphere 52-ABB-am Jamaican Patois, known locally as Patois (Patwa or Patwah) and called Jamaican Creole by linguists, is an 0:00 MENU English-based creole language with West African influences (a Female patois speaker saying two majority of non-English loan words of Akan origin)[6] spoken sentences primarily in Jamaica and among the Jamaican diaspora; it is spoken by the majority of Jamaicans as a native language. Patois developed in the 17th century when slaves from West and Central Africa were exposed to, learned and nativized the vernacular and dialectal forms of English spoken by the slaveholders: British English, Scots, and Hiberno-English. Jamaican Creole exhibits a gradation between more conservative creole forms that are not significantly mutually [7] intelligible with English, and forms virtually identical to A Jamaican Patois speaker [8] Standard English. discussing the usage of the dialect, recorded for Wikitongues. Jamaicans refer to their language as Patois, a term also used as a lower-case noun as a catch-all description of pidgins, creoles, dialects, and vernaculars. -

Limon Creole Phrases: a Vehicle for Linguistic and Cultural 1 Preservation

Limon Creole Phrases: A Vehicle for Linguistic and Cultural 1 Preservation (Frases de criollo limonense: vehículo para la conservación lingüística y cultural) 2 Ginneth Pizarro Chacón Universidad Nacional, Costa Rica 3 Damaris Cordero Badilla Universidad Nacional, Costa Rica AbstrAct Phrases and idiomatic expressions used in everyday speech in Limon Cre- ole by a group of elderly people have been collected in the province of Li- mon, Costa Rica, to preserve those phrases as part of their legacy to future generations. Considering the age factor, the information was gathered by applying a questionnaire to 50 native speakers of Limon Creole. Recom- mendations are provided, based on the results of the study. resumen Se recogen frases y expresiones idiomáticas del criollo limonense del habla cotidiana de un grupo de ancianos en la provincia de Limón, Costa Rica, con el fin de preservarlas como parte del patrimonio lingüístico regional. La información fue recolectada mediante un cuestionario a cincuenta infor- mantes del criollo limonense, considerando el factor etario. Con base en los resultados del estudio se plantean recomendaciones pertinentes. 1 Recibido: 28 de febrero de 2015; aceptado: 30 de agosto de 2015. 2 Escuela de Literatura y Ciencias del Lenguaje. Correo electrónico: [email protected] 3 Escuela de Literatura y Ciencias del Lenguaje. Correo electrónico: [email protected] Letras 58 (2015), ISSN 1409-424X; EISSN 2215-4094 91 Pizarro • Cordero Letras 58 (2015) Keywords: Limon Creole; idiomatic expressions; linguistic diversity; age factors Palabras clave: criollo limonense; expresiones idiomáticas; diversidad lin- güística; criterios etarios Introduction Phraseological units are a common feature of languages; these expressions become used and recognized as representative elements of a culture. -

Aruba Abstracts 2014

ABSTRACTS SCL/SPCL/ACBLPE CONFERENCE 2014 Abstracts of Papers to be presented at the 20 th Biennial Conference of the Society for Caribbean Linguistics, being held in conjunction with the Society for Pidgin and Creole Linguistics (SPCL) and the Associação de Crioulos de Base Lexical Portuguesa e Espanhola (ACBLPE) at th e Holiday Inn Resort, Aruba from 5 to 8 August 2014. ---◊◊-◊◊◊◊◊◊---- ALLEYNE, Mervyn C. (Keynote(Keynote)))) The University of the West Indies, MonaMona////Universidad de Puerto Rico, Río Piedras (Retired) A Reformist Approach to the "Creole" Concept The wider perspective of this essay is The Naming of the “New World” (sic), the appropriation by the new rulers and classifiers of the prerogative of “naming” and thereby of setting the semantic structures and the significant symbols in their interests and favour. Examples such as mulatto and the use of colour terms abound to refer to the different ethnic groups, highly positive in the case of “whit e” and extremely negative in all the other cases: black, red, yellow. The naming of the new languages is also a very instructive example. This essay interrogates the meanings and values of the names given to the languages which emerged in the New World (si c) which are all misleading and offensive and should be rejected in the same way that other terms such as “Coolie”, nigger”, “black”, “mulatto”, personal names and street names, etc. have been rejected in the cleaning -up sweep of post- colonial reform. Thi s essay concentrates on “creole”, as in “Trinidadians speak a creole”; it also deals with two other more offensive terms/concepts: “patois” and “pidgin”.