Faculty of Medicine 60Th Annual Refresher Course for Family Physicians

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SSHRC Forum July 11-12

SSHRC “MOBILIZING KNOWLEDGE FOR ELDER EMPOWERMENT” FORUM TRANSFERRING LESSONS ON COORDINATION OF SOCIAL SERVICES FOR OLDER PEOPLE JULY 11-12, 2019 8:30 AM - 5:00 PM McGill University Institute of Health Sciences Education Lady Meredith House, Ground floor 1110, Pine Avenue West Montreal, QC H3A 1A3 https://elderempowerment.weebly.com SSHRC MOBILIZING KNOWLEDGE FOR ELDER EMPOWERMENT FORUM 2019 PRE-CONFERENCE Wednesday, July 10, 5pm - 7pm WELCOME DRINKS (M-KEE FORUM) Le Mezz Bar, Le Cantlie Hotel Mezzanine level (one floor up) 1110 Sherbrooke Street West Montreal, QC H3A 1G9 DAY 1 Thursday, July 11, 8:30am - 5:00pm WELCOME 8:30 - 8:45 am Arrival, Coffee INTRODUCTION 8:45am: The notion of social health Dr. Peter Nugus 8:50am: Social health as networks Ms. Maud Mazaniello-Chézol 8:55am: Perspectives on health Ms. Valérie Thomas 9:05am: Health and social care in Canada Dr. Émilie Dionne 9:10am: The Québec policy context: present and future The Hon. Carlos Leitão, MP 1 SSHRC MOBILIZING KNOWLEDGE FOR ELDER EMPOWERMENT FORUM 2019 DAY 1 (cont.) Thursday, July 11, 8:30am - 5:00pm WHAT ARE THE CHALLENGES IN DELIVERING OR ADVOCATING FOR SOCIAL HEALTH? Facilitator: Dr. Yvonne Steinert 9:20am - 10:35am Mr. Danis Prud’homme Ms. Laura Tamblyn-Watts Ms. Sheri McLeod Ms. Seeta Ramdass and Ms. Amy Ma Ms. Moira MacDonald 10:35am - 10:45am: Coffee break 10:45am - 11:45am: Discussion 2 SSHRC MOBILIZING KNOWLEDGE FOR ELDER EMPOWERMENT FORUM 2019 DAY 1 (cont.) Thursday, July 11, 8:30am - 5:00pm WHAT ARE THE CORE CONCEPTS, INITIATIVES AND OUTCOMES FOR SOCIAL HEALTH? Facilitator: Dr. -

Health Sciences Programs, Courses and University Regulations 2015-2016

Health Sciences Programs, Courses and University Regulations 2015-2016 This PDF excerpt of Programs, Courses and University Regulations is an archived snapshot of the web content on the date that appears in the footer of the PDF. Archival copies are available at www.mcgill.ca/study. This publication provides guidance to prospects, applicants, students, faculty and staff. 1 . McGill University reserves the right to make changes to the information contained in this online publication - including correcting errors, altering fees, schedules of admission, and credit requirements, and revising or cancelling particular courses or programs - without prior notice. 2 . In the interpretation of academic regulations, the Senate is the ®nal authority. 3 . Students are responsible for informing themselves of the University©s procedures, policies and regulations, and the speci®c requirements associated with the degree, diploma, or certi®cate sought. 4 . All students registered at McGill University are considered to have agreed to act in accordance with the University procedures, policies and regulations. 5 . Although advice is readily available on request, the responsibility of selecting the appropriate courses for graduation must ultimately rest with the student. 6 . Not all courses are offered every year and changes can be made after publication. Always check the Minerva Class Schedule link at https://horizon.mcgill.ca/pban1/bwckschd.p_disp_dyn_sched for the most up-to-date information on whether a course is offered. 7 . The academic publication year begins at the start of the Fall semester and extends through to the end of the Winter semester of any given year. Students who begin study at any point within this period are governed by the regulations in the publication which came into effect at the start of the Fall semester. -

Lady Meredith House – Mcgill

Project Brief: Lady Meredith House – McGill A Restoration fit for a Lady. In 1894, Sir Vincent Meredith and his wife, Lady Meredith, commissioned architect Edward Maxwell to build them a house on land gifted to them by Lady Meredith’s father, located in the Golden Square mile area of Montreal. The Queen Anne style home, with towers, stepped windows and high chimneys, became known as Ardvarna and remained their residence until 1941 when Lady Meredith gave the house and land to the Royal Victoria Hospital for use as a nurses residence. Years later, McGill University acquired the house and remains the owner to this day. Following an attempted arson, the house was completely renovated in 1990 by architects Gersovitz, Becker, and Moss. PROJECT HIGHLIGHTS: Name: Lady Meredith House Location: 1110 Avenue de Pins Project Type: Historical Renovation Building Type: Queen Anne Home Year: 1990 Product Series: Marvin Clad Product Types: Single Hungs, Casements, Awnings, Roundtops, Bays Builder: Marien Oldham Ltd. Based on past experience with similar historic renovations, along with their reputation of delivering quality and craftsmanship, Marvin was chosen by the architects to be a key player in this project. Marvin provided 162 units total to the renovation including Clad Single Hungs, Casements, Awnings, Roundtops, and Bays combining Energy Efficiency with Architectural Accuracy. Today, the Lady Meredith House at McGill is a National Historic Site of Canada and still fully functional. ©2018 Marvin Windows and Doors. All rights reserved. ®Registered trademark of Marvin Windows and Doors. Learn more at MarvinCanada.com. -

Grad Units Section 9, 1999-2000 Mcgill University Graduate Studies Calendar

MECHANICAL ENGINEERING Combustion, shock wave physics and vapour explosions: 47 Mechanical Engineering dust combustion, solid and liquid propellants, explosion hazard, and nuclear reactor safety. Department of Mechanical Engineering Computational fluid dynamics and heat transfer: turbulent, Macdonald Engineering Building reacting and multiphase flows in engineering equipment and in the 817 Sherbrooke Street West environment. Montreal, QC Fluid-structure interactions and dynamics: vibrations and Canada H3A 2K6 instabilities of cylindrical bodies, fluidelasticity, aeroelasticity, Telephone: (514) 398-6281 dynamics of shells containing axial and annular flows. Fax: (514) 398-7365 Email: [email protected] Manufacturing and Industrial engineering: thermoelastic Website: http://www.mecheng.mcgill.ca effects in machine tools, functional behaviour of machined surfaces, optimization in production systems. Chair — S.J. Price Robotics and automation: artificial intelligence based simulation Chair of Graduate Program — N. Hori of industrial processes, design optimization of manipulators, finite automata, geometric modeling and control systems. 47.1 Staff Solid mechanics: composite materials, fracture, fatigue and Emeritus Professors reliability, microscopic and macroscopic approaches. D.R. Axelrad; M.Eng.Sc.(Sydney), D.Sc.Eng.(Vienna), M.N.A.Sc., Space dynamics: orbital analysis, large space structures, space F.I.A.S.(Berlin), M.G.A.M.M.(Germany), Eng. manipulators and tethered satellites. R. Knystautas; B.Eng., M.Eng., Ph.D.(McG.), Eng. W. Bruce; B.A.Sc., M.A.Sc.(Tor.), Eng. 47.3 Admission Requirements J. Cherna; Dipl.Eng.(Swiss Fed. Inst.), Eng., F.E.I.C. B.G. Newman; M.A.(Cantab.), Ph.D.(Syd.), Eng., F.C.A.S.I., The general rules of the Faculty of Graduate Studies apply. -

Mapping Landscapes and Minding Gaps: the Road Towards Evidence Informed Health Professions Education

The Centre for Medical Education & The Faculty Development Office MEDICAL EDUCATION ROUNDS Mapping Landscapes and Minding Gaps: The Road Towards Evidence Informed Health Professions Education ALIKI THOMAS, PhD, OT (C), Erg. Knowledge Exchange and Education in the Health Professions (K.E.E.P) Lab Assistant Professor, School of Physical and Occupational Therapy Research Scientist, Center for Medical Education Faculty of Medicine, McGill University Centre for Interdisciplinary Research in Rehabilitation of Greater Montreal (CRIR) November 30, 2017 16h00 to 17h30 Meakins Amphitheatre, 5th floor, room 521 McIntyre Medical Sciences Building There is a growing and robust body of research in health professions education. Findings from this evidence base may be used to inform educational practice and policy decisions and ensure accountability to learners and society in providing meaningful and effective education. The goals of the presentation are to: provide an overview of the evidence-informed health professions education movement, includ- ing key ongoing conversations and debates; address the urgency of ‘mapping’ existing educational practices; and highlight the fac- tors that may influence educators’ use of research evidence. The presentation will demonstrate how the emerging field of implementation science provides a useful lens through which to investigate the nature and impact of evidence-informed educational practices and policies in the health professions. ALIKI THOMAS is an occupational therapist and graduate of McGill University. She earned a doc- torate in educational psychology with a major in instructional psychology and a minor in applied cognitive science. She completed post-doctoral training in knowledge translation for evidence-based practice at McMaster University’s School of Rehabilitation Sciences and CanChild Center for Child- hood Disability Research. -

Tableau Sypnotique - Amiante

Nombre d'universités dans le 19 56,18% 332 Oui (Présence d'amiante) réseau Nombre d'universités ayant 19 16,41% transmis leurs données 97 Non (Pas d'amiante) Nombre total de bâtiments présentés 591 20,30% 120 Info non disponible dans le tableau 7,11% 42 Autres - Présence d'amiante, mais données partielles Tableau sypnotique - Amiante Présence d'amiante ou de matériaux susceptibles d'en Localisation de la majorité (>80%) de l'amiante ou des matériaux susceptibles d'en Code de l'organisme Nom de l'organisme Code de l'édifice Nom de l'édifice Année de construction1 Le bâtiments a-t-il été désamianté (OUI/NON) Commentaires contenir contenir (murs, planfond, calorifuge, plancher, isolant, tous, autres) (OUI/NON/INFO NON DISPO) 981000 Université Bishop's 1 JOHN BASSETT LIBRARY 1958 OUI Plâtre - Crépis OUI - AMIANTE RÉSIDUEL N-ACCESSIBLE Pour l'Université Bishop's, 20 bâtiments contenant de l'amiante sur un total de 37, revenant à 54 % 981000 Université Bishop's 2 CENTENNIAL THEATRE 1967 OUI Calorifuge NON 981000 Université Bishop's 3 DEWHURST DINING HALL 1967 OUI Calorifuge OUI - AMIANTE RÉSIDUEL ACCÉSIBLE PAR ENDROIT 981000 Université Bishop's 6 HAMILTON 1963 OUI Calorifuge OUI - DÉSAMIANTAGE PAR SECTEUR/PROJET Certains classes / corridors 981000 Université Bishop's 7 JOHNSON 1861 OUI Calorifuge OUI - DÉSAMIANTAGE PAR SECTEUR/PROJET 981000 Université Bishop's 8 MCGREER 1846 OUI Plâtre - Crépis NON 981000 Université Bishop's 10 MORRIS HOUSE 1890 OUI Calorifuge OUI - AMIANTE RÉSIDUEL ACCÉSIBLE PAR ENDROIT 1984 Extension 981000 Université Bishop's -

Airbase 6417

1 8 Indoor Air Quality Update September 1992 The building had a constant-air-volume venUla air intake to 10 cfmpp. The lowest they could tion system with an economizer. A single air in achieve was 20.4 cfmpp. Neither did they reach take was on the 11th floor. During the study, 50 cfmpp, achieving only 33 cfmpp one week 0 fresh air volume was supposed to vary weekly and 47.5 cfmpp the other. on each floor from 10 cubic feet per minute per This led them to recommend that future studies person (cfmpp). the Montreal standard: to 20 using this technique limit the attempt to the cfmpp, the ASHRAE standard: and 50 cfmpp, a two extreme levels, bettering the chance for a standard proposed by the Ontario Department greater variance. of Labour. The building operator and engineer, the only ones who knew the ventilation level Both time and the questionnaire type were im each week, overrode the economizer cycle and portant in results reported by the subjects. used the building's heating and cooling systems, Those respondents who used an open-ended rather than outside air, to maintain temperature questionnaire reported fewer symptoms as the and humidity. study went on, ranging between 11 o/o and 36% lower than those respondents with direct probe Measuring the Results questionnaires. Each Wednesday during the six weeks of the Researchers conclude from the temporal study, the researchers measured temperature, phenomenon that future researchers should humidity, and C02 three times at 10 work sites allow for the variation when designing a study. -

Kumagai Flyer.Pub

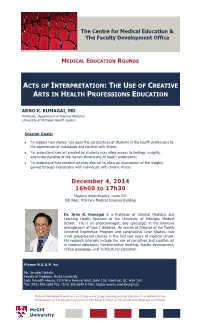

The Centre for Medical Education & The Faculty Development Office MEDICAL EDUCATION ROUNDS ACTS OF INTERPRETATION: THE USE OF CREATIVE ARTS IN HEALTH PROFESSIONS EDUCATION ARNO K. KUMAGAI, MD Professor, Department of Internal Medicine University of Michigan Health System Session Goals: To explore how stories may open the perspectives of students in the health professions to the experiences of individuals and families with illness; To understand how art created by students may allow access to feelings, insights, and understanding of the human dimensions of health professions; To understand how creative art may also act to allow an assessment of the insights gained through interactions with individuals with chronic illness. December 4, 2014 16h00 to 17h30 Meakins Amphitheatre, room 521 5th floor, McIntyre Medical Sciences Building Dr. Arno K. Kumagai is a Professor of Internal Medicine and Learning Health Sciences at the University of Michigan Medical School. He is an endocrinologist, and specializes in the intensive management of type 1 diabetes. He serves as Director of the Family Centered Experience Program and Longitudinal Case Studies, two small group-based courses in the first two years of medical school. His research interests include the use of narratives and creative art in medical education, transformative learning, faculty development, critical pedagogy, and multicultural education. Please R.S.V.P. to: Ms. Jennifer Nicholls Faculty of Medicine, McGill University Lady Meredith House, 1110 Pine Avenue West, Suite 103, Montreal, QC H3A 1A3 Tel: (514) 398-2698 Fax: (514) 398-6649 E-Mail: [email protected] Medical Education Rounds are a self-approved group learning activity (Section 1) as defined by the Maintenance of Certification program of The Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada McGill University . -

Principal's Message

Principal’s Message 2008-09 Welcome to McGill! For more than 185 years, McGill has distinguished itself as one of the world’s great public universities, renowned for outstanding students, professors and alumni, for achievement in teaching and research, and for its distinctive international character. As one of the top 12 universities in the world, McGill’s defi ning strengths include its unwavering commitment to excellence, and a willingness to be judged by the highest standards. And by these standards, McGill has excelled far beyond any reasonable expectations. We have produced a disproportionate number of Nobel laureates and Rhodes scholars. Olympians, award-winning authors and musicians, astronauts, medical pioneers and world-famous leaders in all walks of life are counted among our alumni — remarkable individuals who have shaped our society and the course of history itself in profound ways. As students you are at the core of all that we do. Your time at McGill offers more than an excellent education. It is a critical period of personal and intellectual discovery and growth, and one that will help shape your understanding of the world. By choosing McGill, you are following in the footsteps of almost 200,000 living McGill alumni across the globe and making a commitment to excellence, as they did. And, while a lot is expected of you, McGill gives you the means to succeed. All of McGill’s 21 faculties and professional schools strive to offer the best education possible. By joining the McGill community of scholars, you will experience the University’s vibrant learning environment and active and diverse campus life, which support both academic progress and personal development. -

Nouvelles Avancées En Reproduction Et Développement

BREAKTHROUGHS IN REPRODUCTION AND DEVELOPMENT · NOUVELLES AVANCÉES EN REPRODUCTION ET DÉVELOPPEMENT Research Day Centre for the Study of Reproduction (CSR) at McGill & the Human Reproduction and Development Axis of the Research Institute of the MUHC Wednesday, May 1, 2013 La Plaza - Holiday Inn Montréal Midtown 420 Sherbrooke Ouest Montréal, Québec ______________________________________________________________________________ BREAKTHROUGHS IN REPRODUCTION AND DEVELOPMENT Research Day 2013 Centre for the Study of Reproduction (CSR) at McGill & the Human Reproduction and Development axis of the RI-MUHC Wednesday, May 1, 2013 La Plaza - Holiday Inn Montréal Midtown, 420 Sherbrooke Ouest, Montréal, Québec 8:00 AM Registration and coffee / Poster set-up 8:50 Opening remarks: Dr. Martine Culty 9:00 Dr. Stephanie Seminara, Harvard Medical School, Reproductive Endocrine Unit at Massachusetts General Hospital, “The Hypothalamic Control Of Reproduction: A Kiss To Remember” – introduced by Dr. Daniel Bernard 9:45-10:45 Oral presentations (Chairs: Michelle Collins and Karl Vieux) O-01. Jérôme Fortin. “Gonadotrope Expression Of Smad4 Is Required For Normal FSH Synthesis And Fertility In Mice” O-02. Stephany El-Hayek. “Follicle-stimulating Hormone Regulates Contact And Communication Within The Mouse Ovarian Follicle” O-03. Dayananda Siddappa. “Transient Inhibition Of Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Activity In Preovulatory Follicles Abolishes The Ovulatory Response To Gonadotropins In Mice” O-04. Serge McGraw. “Sustained Loss Of DNA Methylation At Imprinted-Like Loci Following Transient DNMT1 Deficiency In Mouse ES Cells” 10:45-11:05 Health Break 11:05-11:35 Dr. Yojiro Yamanaka, Assistant Professor, Goodman Cancer Research Centre, Department of Human Genetics, McGill University, “Specification And Allocation Of The First Embryonic Lineages In The Mouse Blastocyst” – introduced by Dr. -

Faculty of Medicine Programs, Courses and University Regulations 2018-2019

Faculty of Medicine Programs, Courses and University Regulations 2018-2019 This PDF excerpt of Programs, Courses and University Regulations is an archived snapshot of the web content on the date that appears in the footer of the PDF. Archival copies are available at www.mcgill.ca/study. This publication provides guidance to prospects, applicants, students, faculty and staff. 1 . McGill University reserves the right to make changes to the information contained in this online publication - including correcting errors, altering fees, schedules of admission, and credit requirements, and revising or cancelling particular courses or programs - without prior notice. 2 . In the interpretation of academic regulations, the Senate is the ®nal authority. 3 . Students are responsible for informing themselves of the University©s procedures, policies and regulations, and the speci®c requirements associated with the degree, diploma, or certi®cate sought. 4 . All students registered at McGill University are considered to have agreed to act in accordance with the University procedures, policies and regulations. 5 . Although advice is readily available on request, the responsibility of selecting the appropriate courses for graduation must ultimately rest with the student. 6 . Not all courses are offered every year and changes can be made after publication. Always check the Minerva Class Schedule link at https://horizon.mcgill.ca/pban1/bwckschd.p_disp_dyn_sched for the most up-to-date information on whether a course is offered. 7 . The academic publication year begins at the start of the Fall semester and extends through to the end of the Winter semester of any given year. Students who begin study at any point within this period are governed by the regulations in the publication which came into effect at the start of the Fall semester. -

Academic Units: EP to MU , 2003-2004 Graduate And

P. Brassard, B.Sc.(Montr.), M.Sc.(McG), M.D.(Montr.), FRCPC, 29 Epidemiology and Biostatistics CSPQ (PT) N. Dendukuri; M.Sc.(Indian I.T.), Ph.D.(McG) (PT) Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics R.W. Platt; M.Sc.(Man.), Ph.D.(Wash.) 1020 Pine Avenue West Y. Robitaille B.Sc.(Montr.), Ph.D.(McG.) (PT) Montreal, QC H3A 1A2 G. Tan; D.Phil.(Oxon) (PT) Canada Associate Members Telephone: (514) 398-6269 Dentistry: J. Feine; Family Medicine: J. Cox, T. Tannenbaum; Fax: (514) 398-4503 Dietetics and Human Nutrition: K. Gray-Donald; Medicine: E-mail: [email protected] A. Barkun, M. Behr, J. Brophy, A. Clarke, P. Dobkin, Web site: www.mcgill.ca/epi-biostat M. Eisenberg, P. Ernst, K. Flegel, M. Goldberg, S. Grover, S. Kahn, E. Latimer, N. Mayo, L. Pilote, E. Rahme, Chair — R.Fuhrer K. Schwartzman, I. Shrier; Psychiatry: E. Fombonne, N. Frasure-Smith, G. Galbaud du Fort; Surgery: J. Sampalis 29.1 Staff Adjunct Professors M. Baltzan; Direction régionale de la santé publique: R. Allard, Emeritus Professors R. Lessard, R. Massé, E. Robinson, E. Roy; Hopital Hôtel-Dieu: M.R. Becklake; M.B.B.Ch., M.D.(Witw.), F.R.C.P. J. Lelorier; Inst. Armand Frappier: J. Siemiatycki; Statistics Can- F.D.K. Liddell; M.A.(Cantab.), Ph.D.(Lond.) ada: J. Berthelot; U. Liege: F-A. Allaert; U. de Montréal: J.C. McDonald; M.B. B.S., M.D.(Lond.), M.Sc.(Harv.), Y. Moride; U. of Toronto: M. Hodge M.R.C.P.(Lond.), F.R.C.P.(C) W.O.