The Rise of the Alt-Right

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

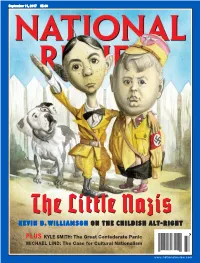

The Little Nazis KE V I N D

20170828 subscribers_cover61404-postal.qxd 8/22/2017 3:17 PM Page 1 September 11, 2017 $5.99 TheThe Little Nazis KE V I N D . W I L L I A M S O N O N T H E C HI L D I S H A L T- R I G H T $5.99 37 PLUS KYLE SMITH: The Great Confederate Panic MICHAEL LIND: The Case for Cultural Nationalism 0 73361 08155 1 www.nationalreview.com base_new_milliken-mar 22.qxd 1/3/2017 5:38 PM Page 1 !!!!!!!! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! "e Reagan Ranch Center ! 217 State Street National Headquarters ! 11480 Commerce Park Drive, Santa Barbara, California 93101 ! 888-USA-1776 Sixth Floor ! Reston, Virginia 20191 ! 800-USA-1776 TOC-FINAL_QXP-1127940144.qxp 8/23/2017 2:41 PM Page 1 Contents SEPTEMBER 11, 2017 | VOLUME LXIX, NO. 17 | www.nationalreview.com ON THE COVER Page 22 Lucy Caldwell on Jeff Flake The ‘N’ Word p. 15 Everybody is ten feet tall on the BOOKS, ARTS Internet, and that is why the & MANNERS Internet is where the alt-right really lives, one big online 35 THE DEATH OF FREUD E. Fuller Torrey reviews Freud: group-therapy session The Making of an Illusion, masquerading as a political by Frederick Crews. movement. Kevin D. Williamson 37 ILLUMINATIONS Michael Brendan Dougherty reviews Why Buddhism Is True: The COVER: ROMAN GENN Science and Philosophy of Meditation and Enlightenment, ARTICLES by Robert Wright. DIVIDED THEY STAND (OR FALL) by Ramesh Ponnuru 38 UNJUST PROSECUTION 12 David Bahnsen reviews The Anti-Trump Republicans are not facing their challenges. -

Does Large Family Size Predict Political Centrism? Benjamin Schmidt

Sigma: Journal of Political and International Studies Volume 33 Article 8 2016 Does Large Family Size Predict Political Centrism? Benjamin Schmidt Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/sigma Part of the International and Area Studies Commons, and the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Schmidt, Benjamin (2016) "Does Large Family Size Predict Political Centrism?," Sigma: Journal of Political and International Studies: Vol. 33 , Article 8. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/sigma/vol33/iss1/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sigma: Journal of Political and International Studies by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Does Large Family Size Predict Political Centrism? by Benjamin Schmidt Introduction Suggesting that voting might be correlated with the number of children vot ers have has been rare but not unheard of in the last decade. In a 2004 article for American Conservative, Steve Sailer noted a correlation between states with higher birth rates among white voters and the support for incumbent Republican Presi dent George W. Bush. Sailer recognized that Bush won the nineteen states with the highest white fertility while Senator John Kerry won the sixteen with the lowest (2004). He also suggested that the lifestyle preferences of white, conservative par ents might be to blame for the apparent Republican tilt among states with higher birth rates. A similar trend occurred again in 2012 when majorities in every state with fertility rates higher than 70 per 1,000 women went to Mitt Romney, while all states with fertility rates below 60 per 1,000 women went to Barack Obama (Sandler 2012). -

The Demise of the African American Baseball Player

LCB_18_2_Art_4_Standen (Do Not Delete) 8/26/2014 6:33 AM THE DEMISE OF THE AFRICAN AMERICAN BASEBALL PLAYER by Jeffrey Standen* Recently alarms were raised in the sports world over the revelation that baseball player agent Scott Boras and other American investors were providing large loans to young baseball players in the Dominican Republic. Although this practice does not violate any restrictions imposed by Major League Baseball or the MLB Players Association, many commentators have termed this funding practice of dubious ethical merit and at bottom exploitative. Yet it is difficult to distinguish exploitation from empowerment. Refusing to lend money to young Dominican players reduces the money invested in athletes. The rules of baseball and the requirements of amateurism preclude similar loans to American-born baseball players. Young ballplayers unlucky enough to be born in the United States cannot borrow their training expenses against their future earning potential. The same limitations apply in similar forms to athletes in other sports, yet baseball presents some unique problems. Success at the professional level in baseball involves a great deal of skill, attention to detail, and supervised training over a long period of time. Players from impoverished financial backgrounds, including predominately the African American baseball player, have been priced out of the game. American athletes in sports that, like baseball, require a significant commitment of money over time have not been able to fund their apprenticeships through self-generated lending markets. One notable example of self-generated funding is in the sport of golf. To fund their career goals, American golfers raise money through a combination of debt and equity financing. -

Small Island

We're a Small Island: The Greening of Intolerance by Sarah Sexton, Nicholas Hildyard and Larry Lohmann, The Corner House, UK presentation at Friends of the Earth (England and Wales), 7th April 2005 Introduction (by Sarah Sexton) For those of you who remember your school days, or if you have 16-year-olds among your family and friends, you'll know that April/May is nearly GCSE exam time, 1 a time of revision, panic and ... set books. One on this year's syllabus is A Tale of Two Cities . (If you were expecting me to say Bill Bryson's Notes From A Small Island , or even better, Andrea Levy's Small Island , they're for next year. 2) Charles Dickens's story about London and Paris is set at the time of the French Revolution, 1789 onwards, a time when the English hero—I won't tell you what happens at the end just in case you haven't seen the film—didn't need an official British passport to travel to another country, although British sovereigns had long issued documents requesting "safe passage or pass" to anyone in Britain who wanted to travel abroad. It was in 1858, some 70 years later, that the UK passport became available only to United Kingdom nationals, and thus in effect became a national identity document as well as an aid to travel. 3 A Tale of Two Cities was published one year later in 1859. These days, students are encouraged to do more field work than when I was at school. -

The Changing Face of American White Supremacy Our Mission: to Stop the Defamation of the Jewish People and to Secure Justice and Fair Treatment for All

A report from the Center on Extremism 09 18 New Hate and Old: The Changing Face of American White Supremacy Our Mission: To stop the defamation of the Jewish people and to secure justice and fair treatment for all. ABOUT T H E CENTER ON EXTREMISM The ADL Center on Extremism (COE) is one of the world’s foremost authorities ADL (Anti-Defamation on extremism, terrorism, anti-Semitism and all forms of hate. For decades, League) fights anti-Semitism COE’s staff of seasoned investigators, analysts and researchers have tracked and promotes justice for all. extremist activity and hate in the U.S. and abroad – online and on the ground. The staff, which represent a combined total of substantially more than 100 Join ADL to give a voice to years of experience in this arena, routinely assist law enforcement with those without one and to extremist-related investigations, provide tech companies with critical data protect our civil rights. and expertise, and respond to wide-ranging media requests. Learn more: adl.org As ADL’s research and investigative arm, COE is a clearinghouse of real-time information about extremism and hate of all types. COE staff regularly serve as expert witnesses, provide congressional testimony and speak to national and international conference audiences about the threats posed by extremism and anti-Semitism. You can find the full complement of COE’s research and publications at ADL.org. Cover: White supremacists exchange insults with counter-protesters as they attempt to guard the entrance to Emancipation Park during the ‘Unite the Right’ rally August 12, 2017 in Charlottesville, Virginia. -

Identity Evropa

AGAINST IDENTITY EVROPA AGAINST THE ALT RIGHT Big Nazi On Campus May 15, 2016 ON FRIDAY, May 6th, white nationalist Richard Spencer, President and director of National Policy Institute (NPI), (a think tank aimed at mil- lennials and educated adults that puts on conferences), and head of its publishing arm Washington Summit Publishers, arrived just before 3pm at UC Berkeley. Encircled by three other white nationalists, Spen- cer walked from the street through several corridors and hallways until finally making his way to Sproul Plaza where a group of other supporters had already gathered and started to live-stream and hold signs. In doing so, Spencer was stepping out of the world of paid con- ferences and weekly podcasts and into the terrain of street activism. Having announced the event on his twitter 48 hours before hand and working with Red Ice Radio, a live-streaming and in home studio run by a white nationalist married couple, the National Policy Institute along with Identity Europa, the youth wing of the American Freedom Party, (a key organizer for ANP is David Duke’s former right-hand man, Jamie Kelso), a Neo-Nazi formation, was working to create a “virtual rally.” The event itself was billed as a “Safe Space” to talk about race in America, using language common among left-wing, ac- tivist, and anarchist spaces. Before the rally even began, Spencer’s fellow white nationalists at Red Ice were already playing up what they imagined was going to happen that day. “Here is is, the birth of the free speech movement, and all of these liberals aren’t going to be able to stand white people talking about race,” they stated, (as if somehow Further resources Berkeley was devoid of white people doing just that). -

PDF Paved with Good Intentions: the Failure of Race Relations in Contemporary America

PDF Paved With Good Intentions: The Failure Of Race Relations In Contemporary America Jared Taylor - book pdf free Download Paved With Good Intentions: The Failure Of Race Relations In Contemporary America PDF, Read Online Paved With Good Intentions: The Failure Of Race Relations In Contemporary America E- Books, Read Paved With Good Intentions: The Failure Of Race Relations In Contemporary America Full Collection Jared Taylor, Paved With Good Intentions: The Failure Of Race Relations In Contemporary America Full Collection, Paved With Good Intentions: The Failure Of Race Relations In Contemporary America Free Read Online, online pdf Paved With Good Intentions: The Failure Of Race Relations In Contemporary America, Download Free Paved With Good Intentions: The Failure Of Race Relations In Contemporary America Book, by Jared Taylor Paved With Good Intentions: The Failure Of Race Relations In Contemporary America, Jared Taylor epub Paved With Good Intentions: The Failure Of Race Relations In Contemporary America, pdf Jared Taylor Paved With Good Intentions: The Failure Of Race Relations In Contemporary America, Jared Taylor ebook Paved With Good Intentions: The Failure Of Race Relations In Contemporary America, Download pdf Paved With Good Intentions: The Failure Of Race Relations In Contemporary America, Download Paved With Good Intentions: The Failure Of Race Relations In Contemporary America Online Free, Read Best Book Online Paved With Good Intentions: The Failure Of Race Relations In Contemporary America, Read Online Paved With Good -

Why Don't Some White Supremacist Groups Pay Taxes?

Emory Law Scholarly Commons Emory Law Journal Online Journals 2018 Why Don't Some White Supremacist Groups Pay Taxes? Eric Franklin Amarante Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.emory.edu/elj-online Recommended Citation Eric F. Amarante, Why Don't Some White Supremacist Groups Pay Taxes?, 67 Emory L. J. Online 2045 (2018). Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.emory.edu/elj-online/12 This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Emory Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Emory Law Journal Online by an authorized administrator of Emory Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AMARANTE GALLEYFINAL 2/15/2018 12:13 PM WHY DON’T SOME WHITE SUPREMACIST GROUPS PAY TAXES? Eric Franklin Amarante* ABSTRACT A number of white supremacist groups enjoy tax-exempt status. These hate groups do not have to pay federal taxes and people who give money to these groups may take deductions on their personal taxes. This recognition not only results in potential lost revenue for government programs, but it also serves as a public subsidy of racist propaganda and operates as the federal government’s imprimatur of white supremacist activities. This is all due to an unnecessarily broad definition of “educational” that somehow encompasses the activities of universities, symphonies, and white supremacists. This Essay suggests a change in the Treasury Regulations to restrict the definition of educational organizations to refer only to traditional, degree-granting institutions, distance-learning organizations, or certain other enumerated entities. -

The Dark Enlightenment

The Dark Enlightenment Nick Land Part 1: Neo-reactionaries head for the exit March 2, 2012 Enlightenment is not only a state, but an event, and a process. As the designation for an historical episode, concentrated in northern Europe during the 18th century, it is a leading candidate for the ‘true name’ of modernity, capturing its origin and essence (‘Renaissance’ and ‘Industrial Revolution’ are others). Between ‘enlightenment’ and ‘progressive enlightenment’ there is only an elusive difference, because illumination takes time – and feeds on itself, because enlightenment is self-confirming, its revelations ‘self-evident’, and because a retrograde, or reactionary, ‘dark enlightenment’ amounts almost to intrinsic contradiction. To become enlightened, in this historical sense, is to recognize, and then to pursue, a guiding light. There were ages of darkness, and then enlightenment came. Clearly, advance has demonstrated itself, offering not only improvement, but also a model. Furthermore, unlike a renaissance, there is no need for an enlightenment to recall what was lost, or to emphasize the attractions of return. The elementary acknowledgement of enlightenment is already Whig history in miniature. Once certain enlightened truths have been found self-evident, there can be no turning back, and conservatism is pre-emptively condemned – predestined — to paradox. F. A. Hayek, who refused to describe himself as a conservative, famously settled instead upon the term ‘Old Whig’, which – like ‘classical liberal’ (or the still more melancholy ‘remnant’) – accepts that progress isn’t what it used to be. What could an Old Whig be, if not a reactionary progressive? And what on earth is that? Of course, plenty of people already think they know what reactionary modernism looks like, and amidst the current collapse back into the 1930s their concerns are only likely to grow. -

The Alt-Right on Campus: What Students Need to Know

THE ALT-RIGHT ON CAMPUS: WHAT STUDENTS NEED TO KNOW About the Southern Poverty Law Center The Southern Poverty Law Center is dedicated to fighting hate and bigotry and to seeking justice for the most vulnerable members of our society. Using litigation, education, and other forms of advocacy, the SPLC works toward the day when the ideals of equal justice and equal oportunity will become a reality. • • • For more information about the southern poverty law center or to obtain additional copies of this guidebook, contact [email protected] or visit www.splconcampus.org @splcenter facebook/SPLCenter facebook/SPLConcampus © 2017 Southern Poverty Law Center THE ALT-RIGHT ON CAMPUS: WHAT STUDENTS NEED TO KNOW RICHARD SPENCER IS A LEADING ALT-RIGHT SPEAKER. The Alt-Right and Extremism on Campus ocratic ideals. They claim that “white identity” is under attack by multicultural forces using “politi- An old and familiar poison is being spread on col- cal correctness” and “social justice” to undermine lege campuses these days: the idea that America white people and “their” civilization. Character- should be a country for white people. ized by heavy use of social media and memes, they Under the banner of the Alternative Right – or eschew establishment conservatism and promote “alt-right” – extremist speakers are touring colleges the goal of a white ethnostate, or homeland. and universities across the country to recruit stu- As student activists, you can counter this movement. dents to their brand of bigotry, often igniting pro- In this brochure, the Southern Poverty Law Cen- tests and making national headlines. Their appear- ances have inspired a fierce debate over free speech ter examines the alt-right, profiles its key figures and the direction of the country. -

Alone Together: Exploring Community on an Incel Forum

Alone Together: Exploring Community on an Incel Forum by Vanja Zdjelar B.A. (Hons., Criminology), Simon Fraser University, 2016 B.A. (Political Science and Communication), Simon Fraser University, 2016 Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the School of Criminology Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences © Vanja Zdjelar 2020 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY FALL 2020 Copyright in this work rests with the author. Please ensure that any reproduction or re-use is done in accordance with the relevant national copyright legislation. Declaration of Committee Name: Vanja Zdjelar Degree: Master of Arts Thesis title: Alone Together: Exploring Community on an Incel Forum Committee: Chair: Bryan Kinney Associate Professor, Criminology Garth Davies Supervisor Associate Professor, Criminology Sheri Fabian Committee Member University Lecturer, Criminology David Hofmann Examiner Associate Professor, Sociology University of New Brunswick ii Abstract Incels, or involuntary celibates, are men who are angry and frustrated at their inability to find sexual or intimate partners. This anger has repeatedly resulted in violence against women. Because incels are a relatively new phenomenon, there are many gaps in our knowledge, including how, and to what extent, incel forums function as online communities. The current study begins to fill this lacuna by qualitatively analyzing the incels.co forum to understand how community is created through online discourse. Both inductive and deductive thematic analyses were conducted on 17 threads (3400 posts). The results confirm that the incels.co forum functions as a community. Four themes in relation to community were found: The incel brotherhood; We can disagree, but you’re wrong; We are all coping here; and Will the real incel come forward. -

Identitarian Movement

Identitarian movement The identitarian movement (otherwise known as Identitarianism) is a European and North American[2][3][4][5] white nationalist[5][6][7] movement originating in France. The identitarians began as a youth movement deriving from the French Nouvelle Droite (New Right) Génération Identitaire and the anti-Zionist and National Bolshevik Unité Radicale. Although initially the youth wing of the anti- immigration and nativist Bloc Identitaire, it has taken on its own identity and is largely classified as a separate entity altogether.[8] The movement is a part of the counter-jihad movement,[9] with many in it believing in the white genocide conspiracy theory.[10][11] It also supports the concept of a "Europe of 100 flags".[12] The movement has also been described as being a part of the global alt-right.[13][14][15] Lambda, the symbol of the Identitarian movement; intended to commemorate the Battle of Thermopylae[1] Contents Geography In Europe In North America Links to violence and neo-Nazism References Further reading External links Geography In Europe The main Identitarian youth movement is Génération identitaire in France, a youth wing of the Bloc identitaire party. In Sweden, identitarianism has been promoted by a now inactive organisation Nordiska förbundet which initiated the online encyclopedia Metapedia.[16] It then mobilised a number of "independent activist groups" similar to their French counterparts, among them Reaktion Östergötland and Identitet Väst, who performed a number of political actions, marked by a certain