An Investigation Into Prey Selection in the Scottish Wildcat (Felis Silvestris Silvestris)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VII. Bodies, Institutes and Centres

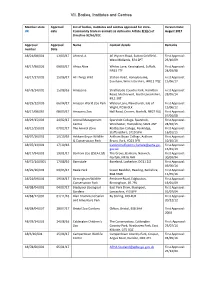

VII. Bodies, Institutes and Centres Member state Approval List of bodies, institutes and centres approved for intra- Version Date: UK date Community trade in animals as defined in Article 2(1)(c) of August 2017 Directive 92/65/EEC Approval Approval Name Contact details Remarks number Date AB/21/08/001 13/03/17 Ahmed, A 46 Wyvern Road, Sutton Coldfield, First Approval: West Midlands, B74 2PT 23/10/09 AB/17/98/026 09/03/17 Africa Alive Whites Lane, Kessingland, Suffolk, First Approval: NR33 7TF 24/03/98 AB/17/17/005 15/06/17 All Things Wild Station Road, Honeybourne, First Approval: Evesham, Worcestershire, WR11 7QZ 15/06/17 AB/78/14/002 15/08/16 Amazonia Strathclyde Country Park, Hamilton First Approval: Road, Motherwell, North Lanarkshire, 28/05/14 ML1 3RT AB/29/12/003 06/04/17 Amazon World Zoo Park Watery Lane, Newchurch, Isle of First Approval: Wight, PO36 0LX 15/06/12 AB/17/08/065 08/03/17 Amazona Zoo Hall Road, Cromer, Norfolk, NR27 9JG First Approval: 07/04/08 AB/29/15/003 24/02/17 Animal Management Sparsholt College, Sparsholt, First Approval: Centre Winchester, Hampshire, SO21 2NF 24/02/15 AB/12/15/001 07/02/17 The Animal Zone Rodbaston College, Penkridge, First Approval: Staffordshire, ST19 5PH 16/01/15 AB/07/16/001 10/10/16 Askham Bryan Wildlife Askham Bryan College, Askham First Approval: & Conservation Park Bryan, York, YO23 3FR 10/10/16 AB/07/13/001 17/10/16 [email protected]. First Approval: gov.uk 15/01/13 AB/17/94/001 19/01/17 Banham Zoo (ZSEA Ltd) The Grove, Banham, Norwich, First Approval: Norfolk, NR16 -

European Rabbits in Chile: the History of a Biological Invasion

Historia. vol.4 no.se Santiago 2008 EUROPEAN RABBITS IN CHILE: THE HISTORY OF A BIOLOGICAL INVASION * ** *** PABLO C AMUS SERGIO C ASTRO FABIÁN J AKSIC * Centro de Estudios Avanzados en Ecología y Biodiversidad (CASEB) . email: [email protected] ** Departamento de Biología, Facultad de Química y Biología; Universidad de Santiago de Chile. Centro de Estudios Avanzados en Ecología y Biodiversidad (CASEB). email: [email protected] *** Departamento de Ecología, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile. Centro de Estudios Avanzados en Ecología y Biodiversidad (CASEB). email: [email protected] ABSTRACT This work analyses the relationship between human beings and their environment taking into consideration the adjustment and eventual invasion of rabbits in Chile. It argues that in the long run, human actions have unsuspected effects upon the environment. In fact rabbits were seen initially as an opportunity for economic development because of the exploitation of their meat and skin. Later, rabbits became a plague in different areas of Central Chile, Tierra del Fuego and Juan Fernández islands, which was difficult to control. Over the years rabbits became unwelcome guests in Chile. Key words: Environmental History, biological invasions, European rabbit, ecology and environment. RESUMEN Este trabajo analiza las relaciones entre los seres humanos y su ambiente, a partir de la historia de la aclimatación y posterior invasión de conejos en Chile, constatando que, en el largo plazo, las acciones humanas tienen efectos e impactos insospechados sobre el medio natural. En efecto, si bien inicialmente los conejos fueron vistos como una oportunidad de desarrollo económico a partir del aprovechamiento de su piel y su carne, pronto esta especie se convirtió en una plaga difícil de controlar en diversas regiones del país, como Chile central, Tierra del Fuego e islas Juan Fernández. -

Conservation of the Wildcat (Felis Silvestris) in Scotland: Review of the Conservation Status and Assessment of Conservation Activities

Conservation of the wildcat (Felis silvestris) in Scotland: Review of the conservation status and assessment of conservation activities Urs Breitenmoser, Tabea Lanz and Christine Breitenmoser-Würsten February 2019 Wildcat in Scotland – Review of Conservation Status and Activities 2 Cover photo: Wildcat (Felis silvestris) male meets domestic cat female, © L. Geslin. In spring 2018, the Scottish Wildcat Conservation Action Plan Steering Group commissioned the IUCN SSC Cat Specialist Group to review the conservation status of the wildcat in Scotland and the implementation of conservation activities so far. The review was done based on the scientific literature and available reports. The designation of the geographical entities in this report, and the representation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the IUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The SWCAP Steering Group contact point is Martin Gaywood ([email protected]). Wildcat in Scotland – Review of Conservation Status and Activities 3 List of Content Abbreviations and Acronyms 4 Summary 5 1. Introduction 7 2. History and present status of the wildcat in Scotland – an overview 2.1. History of the wildcat in Great Britain 8 2.2. Present status of the wildcat in Scotland 10 2.3. Threats 13 2.4. Legal status and listing 16 2.5. Characteristics of the Scottish Wildcat 17 2.6. Phylogenetic and taxonomic characteristics 20 3. Recent conservation initiatives and projects 3.1. Conservation planning and initial projects 24 3.2. Scottish Wildcat Action 28 3.3. -

Baylisascariasis

Baylisascariasis Importance Baylisascaris procyonis, an intestinal nematode of raccoons, can cause severe neurological and ocular signs when its larvae migrate in humans, other mammals and birds. Although clinical cases seem to be rare in people, most reported cases have been Last Updated: December 2013 serious and difficult to treat. Severe disease has also been reported in other mammals and birds. Other species of Baylisascaris, particularly B. melis of European badgers and B. columnaris of skunks, can also cause neural and ocular larva migrans in animals, and are potential human pathogens. Etiology Baylisascariasis is caused by intestinal nematodes (family Ascarididae) in the genus Baylisascaris. The three most pathogenic species are Baylisascaris procyonis, B. melis and B. columnaris. The larvae of these three species can cause extensive damage in intermediate/paratenic hosts: they migrate extensively, continue to grow considerably within these hosts, and sometimes invade the CNS or the eye. Their larvae are very similar in appearance, which can make it very difficult to identify the causative agent in some clinical cases. Other species of Baylisascaris including B. transfuga, B. devos, B. schroeder and B. tasmaniensis may also cause larva migrans. In general, the latter organisms are smaller and tend to invade the muscles, intestines and mesentery; however, B. transfuga has been shown to cause ocular and neural larva migrans in some animals. Species Affected Raccoons (Procyon lotor) are usually the definitive hosts for B. procyonis. Other species known to serve as definitive hosts include dogs (which can be both definitive and intermediate hosts) and kinkajous. Coatimundis and ringtails, which are closely related to kinkajous, might also be able to harbor B. -

Integrating Black Bear Behavior, Spatial Ecology, and Population Dynamics in a Human-Dominated Landscape: Implications for Management

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 8-2017 Integrating Black Bear Behavior, Spatial Ecology, and Population Dynamics in a Human-Dominated Landscape: Implications for Management Jarod D. Raithel Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd Part of the Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons Recommended Citation Raithel, Jarod D., "Integrating Black Bear Behavior, Spatial Ecology, and Population Dynamics in a Human- Dominated Landscape: Implications for Management" (2017). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 6633. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/6633 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INTEGRATING BLACK BEAR BEHAVIOR, SPATIAL ECOLOGY, AND POPULATION DYNAMICS IN A HUMAN-DOMINATED LANDSCAPE: IMPLICATIONS FOR MANAGEMENT by Jarod D. Raithel A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Ecology Approved: _______________________ _______________________ Lise M. Aubry, Ph.D. Melissa J. Reynolds-Hogland, Ph.D. Major Professor Committee Member _______________________ _______________________ David N. Koons, Ph.D. Eric M. Gese, Ph.D. Committee Member Committee Member _______________________ _______________________ Joseph M. Wheaton, Ph.D. Mark R. McLellan, Ph.D. Committee Member Vice President for Research and Dean of the School of Graduate Studies UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 2017 ii Copyright Jarod Raithel 2017 All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Integrating Black Bear Behavior, Spatial Ecology, and Population Dynamics in a Human-Dominated Landscape: Implications for Management by Jarod D. -

ATIC0943 {By Email}

Animal and Plant Health Agency T 0208 2257636 Access to Information Team F 01932 357608 Weybourne Building Ground Floor Woodham Lane www.gov.uk/apha New Haw Addlestone Surrey KT15 3NB Our Ref: ATIC0943 {By Email} 4 October 2016 Dear PROVISION OF REQUESTED INFORMATION Thank you for your request for information about zoos which we received on 26 September 2016. Your request has been handled under the Freedom of Information Act 2000. The information you requested and our response is detailed below: “Please can you provide me with a full list of the names of all Zoos in the UK. Under the classification of 'Zoos' I am including any place where a member of the public can visit or observe captive animals: zoological parks, centres or gardens; aquariums, oceanariums or aquatic attractions; wildlife centres; butterfly farms; petting farms or petting zoos. “Please also provide me the date of when each zoo has received its license under the Zoo License act 1981.” See Appendix 1 for a list that APHA hold on current licensed zoos affected by the Zoo License Act 1981 in Great Britain (England, Scotland and Wales), as at 26 September 2016 (date of request). The information relating to Northern Ireland is not held by APHA. Any potential information maybe held with the Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs Northern Ireland (DAERA-NI). Where there are blanks on the zoo license start date that means the information you have requested is not held by APHA. Please note that the Local Authorities’ Trading Standard departments are responsible for administering and issuing zoo licensing under the Zoo Licensing Act 1981. -

Felis Silvestris, Wild Cat

The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ ISSN 2307-8235 (online) IUCN 2008: T60354712A50652361 Felis silvestris, Wild Cat Assessment by: Yamaguchi, N., Kitchener, A., Driscoll, C. & Nussberger, B. View on www.iucnredlist.org Citation: Yamaguchi, N., Kitchener, A., Driscoll, C. & Nussberger, B. 2015. Felis silvestris. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2015: e.T60354712A50652361. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2015-2.RLTS.T60354712A50652361.en Copyright: © 2015 International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale, reposting or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission from the copyright holder. For further details see Terms of Use. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ is produced and managed by the IUCN Global Species Programme, the IUCN Species Survival Commission (SSC) and The IUCN Red List Partnership. The IUCN Red List Partners are: BirdLife International; Botanic Gardens Conservation International; Conservation International; Microsoft; NatureServe; Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew; Sapienza University of Rome; Texas A&M University; Wildscreen; and Zoological Society of London. If you see any errors or have any questions or suggestions on what is shown in this document, please provide us with feedback so that we can correct or extend the information -

Reproduction and Behaviour of European Wildcats in Species Specific Enclosures

Symposium Biology and Conservation of the European Wildcat (Felis silvestris silvestris) Germany January 21st –23rd 2005 Abstracts Mathias Herrmann, Hof 30, 16247 Parlow, [email protected], Mobil: ++49 +171 9962910 Introduction More than four years after the last meeting of wildcat experts in Nienover, Germany, the NABU (Naturschutzbund Deutschland e.V.) invited for a three day symposium on the conservation of the European wildcat. Since the last meeting the knowledge on wildcat ecology increased a lot due to the field work of several research teams. The aim of the symposium was to bring these teams together to discuss especially questions which could not be solved by one single team due to limited number of observed individuals or special landscape features. The focus was set on the following questions: 1) Hybridization and risk of infection by domestic cat - a threat to wild living populations? 2) Reproductive success, mating behaviour, and life span - what strategy do wildcats have? 3) ffh - reports/ monitoring - which methods should be used? 4) Habitat utilization in different landscapes - species of forest or semi-open landscape? 5) Conservation of the wildcat - which measures are practicable? 6) Migrations - do wildcats have juvenile dispersal? 75 Experts from 9 European countries came to Fischbach within the transboundary Biosphere Reserve "Vosges du Nord - Pfälzerwald" to discuss distribution, ecology and behaviour of this rare species. The symposium was organized by one single person - Dr. Mathias Herrmann - and consisted of oral presentations, posters and different workshops. 2 Scientific program Friday Jan 21st 8:00 – 10:30 registration /optional: Morning excursion to the core area of the biosphere reserve 10:30 Genot, J-C., Stein, R., Simon, L. -

African Wildcat 1 African Wildcat

African Wildcat 1 African Wildcat African Wildcat[1] Scientific classification Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Chordata Class: Mammalia Order: Carnivora Family: Felidae Genus: Felis Species: F. silvestris Subspecies: F. s. lybica Trinomial name Felis silvestris lybica Forster, 1770 The African wildcat (Felis silvestris lybica), also known as the desert cat, and Vaalboskat (Vaal-forest-cat) in Afrikaans, is a subspecies of the wildcat (F. silvestris). They appear to have diverged from the other subspecies about 131,000 years ago.[2] Some individual F. s. lybica were first domesticated about 10,000 years ago in the Middle East, and are among the ancestors of the domestic cat. Remains of domesticated cats have been included in human burials as far back as 9,500 years ago in Cyprus.[3] [4] Physical characteristics The African wildcat is sandy brown to yellow-grey in color, with black stripes on the tail. The fur is shorter than that of the European subspecies. It is also considerably smaller: the head-body length is 45 to 75 cm (17.7 to 29.5 inches), the tail 20 to 38 cm (7.87 to 15 inches), and the weight ranges from 3 to 6.5 kg (6.61 to 14.3 lbs). Distribution and habitat The African wildcat is found in Africa and in the Middle East, in a wide range of habitats: steppes, savannas and bushland. The sand cat (Felis margarita) is the species found in even more arid areas. Skull African Wildcat 2 Behaviour The African wildcat eats primarily mice, rats and other small mammals. When the opportunity arises, it also eats birds, reptiles, amphibians, and insects. -

The Wild Rabbit: Plague, Polices and Pestilence in England and Wales, 1931–1955

The wild rabbit: plague, polices and pestilence in England and Wales, 1931–1955 by John Martin Abstract Since the eighteenth century the rabbit has occupied an ambivalent position in the countryside. Not only were they of sporting value but they were also valued for their meat and pelt. Attitudes to the rabbit altered though over the first half of the century, and this paper traces their redefinition as vermin. By the 1930s, it was appreciated that wild rabbits were Britain’s most serious vertebrate pest of cereal crops and grassland and that their numbers were having a significant effect on agricultural output. Government took steps to destroy rabbits from 1938 and launched campaigns against them during wartime, when rabbit was once again a form of meat. Thereafter government attitudes to the rabbit hardened, but it was not until the mid-1950s that pestilence in the form of a deadly virus, myxomatosis, precipitated an unprecedented decline in their population. The unprecedented decline in the European rabbit Oryctolagus( cuniculus) in the mid- twentieth century is one of the most remarkable ecological changes to have taken place in Britain. Following the introduction of myxomatosis into Britain in September 1953 at Bough Beech near Edenbridge in Kent, mortality rates in excess of 99.9 per cent were recorded in a number of affected areas.1 Indeed, in December 1954, the highly respected naturalist Robin Lockley speculated that 1955 would constitute ‘zero hour for the rabbit’, with numbers being lower by the end of the year than at any time since the eleventh century.2 In spite of the rapid increases in output and productivity which British agriculture experienced in the post-myxomatosis era, the importance of the disease as a causal factor in raising agricultural output has been largely ignored by agricultural historians.3 The academic neglect of the rabbit as a factor influencing productivity is even more apparent in respect of the pre-myxomatosis era, particularly the period before the Second World War. -

Chinese Mountain Cat 1 Chinese Mountain Cat

Chinese mountain cat 1 Chinese mountain cat Chinese Mountain Cat[1] Conservation status [2] Vulnerable (IUCN 3.1) Scientific classification Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Chordata Class: Mammalia Order: Carnivora Family: Felidae Genus: Felis Species: F. bieti Binomial name Felis bieti Milne-Edwards, 1892 Distribution of the Chinese Mountain Cat (in green) The Chinese Mountain Cat (Felis bieti), also known as the Chinese Desert Cat, is a small wild cat of western China. It is the least known member of the genus Felis, the common cats. A 2007 DNA study found that it is a subspecies of Felis silvestris; should the scientific community accept this result, this cat would be reclassified as Felis silvestris bieti.[3] Some authorities regard the chutuchta and vellerosa subspecies of the Wildcat as Chinese Mountain Cat subspecies.[1] Chinese mountain cat 2 Description Except for the colour of its fur, this cat resembles a European Wildcat in its physical appearance. It is 27–33 in (69–84 cm) long, plus a 11.5–16 in (29–41 cm) tail. The adult weight can range from 6.5 to 9 kilograms (14 to 20 lb). They have a relatively broad skull, and long hair growing between the pads of their feet.[4] The fur is sand-coloured with dark guard hairs; the underside is whitish, legs and tail bear black rings. In addition there are faint dark horizontal stripes on the face and legs, which may be hardly visible. The ears and tail have black tips, and there are also a few dark bands on the tail.[4] Distribution and ecology The Chinese Mountain Cat is endemic to China and has a limited distribution over the northeastern parts of the Tibetan Plateau in Qinghai and northern Sichuan.[5] It inhabits sparsely-wooded forests and shrublands,[4] and is occasionally found in true deserts. -

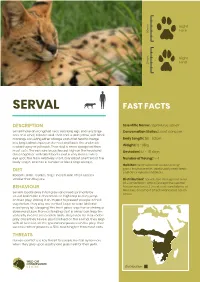

Serval Fact Sheet

Right 50mm Fore Right 50mm Hind SERVAL FAST FACTS DESCRIPTION Scientific Name: Leptailurus serval Servals have an elongated neck, very long legs, and very large Conversation Status: Least concern ears on a small, delicate skull. Their coat is pale yellow, with black markings consisting either of large spots that tend to merge Body Length: 59 - 92cm into longitudinal stripes on the neck and back. The underside is whitish grey or yellowish. Their skull is more elongated than Weight: 12 - 18kg most cats. The ears are broad based, high on the head and Gestation: 67 - 79 days close together, with black backs and a very distinct white eye spot. The tail is relatively short, only about one third of the Number of Young: 1 - 4 body length, and has a number of black rings along it. Habitat: Well-watered savanna long- grass environments, particularly reed beds DIET and other riparian habitats. Rodents, birds, reptiles, frogs, insects and other species smaller than they are. Distribution: Servals live throughout most of sub-Saharan Africa (except the central BEHAVIOUR African rainforest), the deserts and plains of Namibia, and most of Botswana and South Servals locate prey in tall grass and reeds primarily by Africa. sound and make a characteristic high leap as they jump on their prey, striking it on impact to prevent escape in thick vegetation. They also use vertical leaps to seize bird and insect prey by “clapping” the front paws together or striking a downward blow. From a standing start a serval can leap 3m vertically into the air to catch birds.