Measuring and Handling Risk

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Generating Potential Income in a Low Interest Rate World

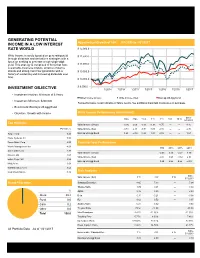

GENERATING POTENTIAL INCOME IN A LOW INTEREST Hypothetical Growth of 10K: 5/1/2013 to 1/31/2017 RATE WORLD $ 12,000.0 Write Income is solely focused on generating yield $ 11,500.0 through dividends and derivatives strategies with a focus on seeking to generate a high single-digit yield. This strategy is comprised of firms that have $ 11,000.0 sustainable business models, attractive balance sheets and strong cash flow generation with a $ 10,500.0 history of sustaining and increasing dividends over time. $ 10,000.0 $ 9,500.0 INVESTMENT OBJECTIVE 1/2014 7/2014 1/2015 7/2015 1/2016 7/2016 1/2017 Investment Horizon: Minimum of 3 Years Write Income (Gross) Write Income (Net) BarCap US Agg Bond Investment Minimum: $200,000 Past performance is not indicative of future results. See additional important disclosures on next page. Benchmark: Barclays US Agg Bond Objective: Growth with Income Write Income Performance (Annualized) Since 1 Mo 3 Mo YTD 1 Yr 3 Yr 5 Yr 10 Yr 5/1/2013 Top Holdings Write Income (Gross) 2.66-0.36-0.36 11.08 4.75 —— 4.16 Portfolio % Write Income (Net) 2.19-0.51-0.51 9.09 2.88 —— 2.30 Target Corp 5.40 BarCap US Agg Bond -2.040.200.20 1.45 2.59 —— 1.67 Cisco Systems Inc 5.38 Exxon Mobil Corp 4.39 Calendar Year Performance Waste Management Inc 4.03 YTD 2016 2015 2013 General Mills Inc 3.87 Write Income (Gross) -0.36 6.53 -2.07 4.10 Invesco Ltd 3.63 Write Income (Net) -0.51 4.63 -3.82 2.85 Eaton Corp PLC 3.62 BarCap US Agg Bond 0.20 2.65 0.55 -2.89 MetLife Inc 3.54 Wal-Mart Stores Inc 3.50 Dow Chemical Co 3.49 Risk Analysis -

Mersberger Financial Group, Inc. Investment Policy Statement

Mersberger Financial Group, Inc. Investment Policy Statement A Fiduciary Approach to Investing Mersberger Financial Group, Inc. Investment Policy Statement Table of Contents Firm Investment Policy Statement.............................................................1 Model 1: MFG Individual Bond Strategy....................................................9 Model 2: MFG Preferred Stock Strategy...................................................13 Model 3: MFG Tactical Equity Model.......................................................17 Model 4: MFG Passive Equity Model.......................................................23 Frequently Asked Questions....................................................................27 Firm Investment Policy Statement Executive Summary The advisors at Mersberger Financial Group, Inc. (which may be referred to as “MFG”, “Us” or “We” throughout this document) has developed an investment policy statement in order to outline the investment philosophy and the investment processes of the advisors. This document also seeks to ensure that the advisors of MFG act in a fiduciary capacity for all clients. We believe it is critical in planning for its client’s futures to form a repeatable and documentable portfolio management process. In addition, MFG believes it is important to have all financial advisors and staff members educated and cognizant of MFG’s investment strategies and philosophy. This approach allows MFG to maintain consistency in it’s investment advice, as well as to always act in the clients best interest. Purpose The purpose of this document is to outline Mersberger Financial Group’s investment philosophy, strategies and procedures. This document will attempt to create a set of standards to hold MFG accountable to, as well as outline a disciplined investment approach for the advisors to follow. We believe having formal investment processes and strategies is crucial, especially in times of market volatility when investment managers may become tempted to deviate from their core strategies. -

Picking the Right Risk-Adjusted Performance Metric

WORKING PAPER: Picking the Right Risk-Adjusted Performance Metric HIGH LEVEL ANALYSIS QUANTIK.org Investors often rely on Risk-adjusted performance measures such as the Sharpe ratio to choose appropriate investments and understand past performances. The purpose of this paper is getting through a selection of indicators (i.e. Calmar ratio, Sortino ratio, Omega ratio, etc.) while stressing out the main weaknesses and strengths of those measures. 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................................. 1 2. The Volatility-Based Metrics ..................................................................................................................... 2 2.1. Absolute-Risk Adjusted Metrics .................................................................................................................. 2 2.1.1. The Sharpe Ratio ............................................................................................................................................................. 2 2.1. Relative-Risk Adjusted Metrics ................................................................................................................... 2 2.1.1. The Modigliani-Modigliani Measure (“M2”) ........................................................................................................ 2 2.1.2. The Treynor Ratio ......................................................................................................................................................... -

Algorithm for Construction of Portfolio of Stocks Using Treynor's Ratio

Munich Personal RePEc Archive Algorithm for construction of portfolio of stocks using Treynor’s ratio Sinha, Pankaj and Goyal, Lavleen Faculty of Management Studies, University of Delhi 7 July 2012 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/40134/ MPRA Paper No. 40134, posted 18 Jul 2012 20:47 UTC Algorithm for construction of portfolio of stocks using Treynor’s ratio Algorithm for construction of portfolio of stocks using Treynor’s ratio Pankaj Sinha Faculty of Management Studies, University of Delhi Lavleen Goyal Indian Institute of Technology, Guwahati Abstract The aim of the paper is to implement the algorithm for selecting stocks from a pool of stocks listed in a single market index like S&P CNX 500(say) and finding the corresponding weights of the stocks in the optimized portfolio using Treynor’s ratio, on the basis of historical data of Indian stock market when the short selling is not allowed. The effectiveness of this algorithm has been demonstrated with an example. Page 1 Algorithm for construction of portfolio of stocks using Treynor’s ratio 1. Introduction Market offers several assets in various formats which are grounds for investing money and gaining returns after specific time periods. Investments are made in view of obtaining highest returns with lowest chance of losing money. The returns are however characterised by the nature of assets and the market factors that influence its pricing everyday. Since the returns cannot be foretold with certainty, the analysis of profitability in an asset becomes an objective of utmost priority in an investment procedure. A technique of judging the behaviour returns from an asset is historical data analysis of the asset with respect to market. -

Investment Performance Performance Versus Benchmark: Return and Sharpe Ratio

Release date 07-31-2018 Page 1 of 20 Investment Performance Performance versus Benchmark: Return and Sharpe Ratio 5-Yr Summary Statistics as of 07-31-2018 Name Total Rtn Sharpe Ratio TearLab Corp(TEAR) -75.30 -2.80 AmerisourceBergen Corp(ABC) 8.62 -2.80 S&P 500 TR USD 13.12 1.27 Definitions Return Sharpe Ratio The gain or loss of a security in a particular period. The return consists of the The Sharpe Ratio is calculated using standard deviation and excess return to income and the capital gains relative to an investment. It is usually quoted as a determine reward per unit of risk. The higher the SharpeRatio, the better the percentage. portfolio’s historical risk-adjusted performance. Performance Disclosure The performance data quoted represents past performances and does not guarantee future results. The investment return and principal value of an investment will fluctuate; thus an investor's shares, when sold or redeemed, may be worth more or less than their original cost. Current performance may be lower or higher than return data quoted herein. Please see the Disclosure Statements for Standardized Performance. ©2018 Morningstar. All Rights Reserved. Unless otherwise provided in a separate agreement, you may use this report only in the country in which its original distributor is based. The information, data, analyses and ® opinions contained herein (1) include the confidential and proprietary information of Morningstar, (2) may include, or be derived from, account information provided by your financial advisor which cannot be verified by Morningstar, (3) may not be copied or redistributed, (4) do not constitute investment advice offered by Morningstar, (5) are provided solely for informational purposes and therefore are not an offer to buy or sell a security, ß and (6) are not warranted to be correct, complete or accurate. -

MONTGOMERY COMMUNITY COLLEGE FOUNDATION 1011 Page Street ∙ Troy, NC 27371 ∙ (910) 898-9603 ∙ [email protected]

MONTGOMERY COMMUNITY COLLEGE FOUNDATION 1011 Page Street ∙ Troy, NC 27371 ∙ (910) 898-9603 ∙ [email protected] The regular meeting of the Foundation Board of Directors of Montgomery Community College will be held on Wednesday, August 12, 2020 at 1:00 p.m. via zoom. Call to Order – Jean Abbott, Foundation President Approval of the Agenda – Jean Abbott, Foundation President – Action Welcome – Jean Abbott Minutes – Jean Abbott ∗ February 12, 2020 Foundation Board Minutes – Appendix A– Action ∗ July 8, 2020 Called Foundation Board Minutes – Appendix B – Action Finance Committee Report – Gary McRae, Finance Committee Chair ∗ 4th Quarter Investment Report – Appendix C ∗ Wells Fargo Presentation – Jay Jacob & Brian Green Nominating Committee Report – Claudia Bulthuis, Nominating Committee Chair ∗ Board Member Recommendations – Appendix D – Action ∗ Election of Officers - Action Treasurer Report – Jeanette McBride, Foundation Treasurer ∗ Fund Statements – Appendix E – Action ∗ Career and College Promise Book Program Update – Appendix F Foundation Reports – Korrie Ervin, Director of Resource Development ∗ 2019-2020 Budget Review – Appendix G ∗ 2020-2021 Budget – Appendix H ∗ 2019-2020 Occupational Scholarships – Appendix I ∗ Grant Updates – Appendix J ∗ 2020 Golf Tournament Update – Appendix J.1 ∗ Non- Event Fall Fundraiser – Appendix K ∗ 3rd Annual Shooting Clay Tournament – Discussion ∗ Veteran’s Day Event ∗ Calendar of Events – Appendix L ∗ 2020 Annual Fund Drive Cumulative Donations – Appendix M President’s Report New Business Adjourn Next Meeting: November 11, 2020 www.montgomery.edu Montgomery Community College Foundation is a 501(c)(3) corporation Appendix A.1 Montgomery Community College Foundation Board Meeting February 12, 2020 The regular meeting of the Foundation Board of Directors of Montgomery Community College was held on Wednesday, February 12, 2020 at noon in the College Boardroom in Capel Hall. -

Chapter 4 Sharpe Ratio, CAPM, Jensen's Alpha, Treynor Measure

Excerpt from Prof. C. Droussiotis Text Book: An Analytical Approach to Investments, Finance and Credit Chapter 4 Sharpe Ratio, CAPM, Jensen’s Alpha, Treynor Measure & M Squared This chapter will continue to emphasize the risk and return relationship. In the previous chapters, the risk and return characteristics of a given portfolio were measured at first versus other asset classes and then second, measured to market benchmarks. This chapter will re-emphasize these comparisons by introducing other ways to compare via performance measurements ratios such the Share Ratio, Jensen’s Alpha, M Squared, Treynor Measure and other ratios that are used extensively on wall street. Learning Objectives After reading this chapter, students will be able to: Calculate various methods for evaluating investment performance Determine which performance ratios measure is appropriate in a variety of investment situations Apply various analytical tools to set up portfolio strategy and measure expectation. Understand to differentiate the between the dependent and independent variables in a linear regression to set return expectation Determine how to allocate various assets classes within the portfolio to achieve portfolio optimization. [Insert boxed text here AUTHOR’S NOTES: In the spring of 2006, just 2 years before the worse financial crisis the U.S. has ever faced since the 1930’s, I visited few European countries to promote a new investment opportunity for these managers who only invested in stocks, bonds and real estate. The new investment opportunity, already established in the U.S., was to invest equity in various U.S. Collateral Loan Obligations (CLO). The most difficult task for me is to convince these managers to accept an average 10-12% return when their portfolio consists of stocks, bonds and real estate holdings enjoyed returns in excess of 30% per year for the last 3-4 years. -

TREYNOR Updated: 31 Mar 2016

TREYNOR Updated: 31 Mar 2016 Use TREYNOR to calculate the Treynor ratio based upon return data. You have the option of computing the Treynor ratio using either simple returns or geometric returns. For simple returns, the Treynor ratio is calculated as the mean of the returns minus the risk-free rate divided by the beta of the returns against the benchmark returns. 푅̅ − 푅푓 푇푅퐸푌푁푂푅 = 훽푅,푅푏 For geometric returns, the Treynor ratio is calculated as the geometric mean of the return minus the risk-free rate divided by the beta of the returns against the benchmark returns. For the sake of consistency, the risk-free rate should be in the same units as the scaling factor. 푠푐푎푙푒 푛 ⁄푛 [(∏푖=1 1 + 푅푖] − 1 푇푅퐸푌푁푂푅 = 훽푅,푅푏 βR,Rb = SLOPE(R,Rb) Syntax Public Shared Function TREYNOR( ByVal R As Double(), ByVal RB As Double(), ByVal RF As Double, ByVal Scale As Double, ByVal Geometric As Boolean,) Arguments R the return value; the percentage return in floating point format (i.e. 10% = .01). R is an expression that returns an Array of Double, or of a type that can be implicitly converted to an Array of Double. RB the benchmark return value. RB is an expression that returns an Array of Double, or of a type that can be implicitly converted to an Array of Double. RF the risk-free rate. RF is an expression that returns a Double, or of a type that can be implicitly converted to Double. Scale the scaling factor used in the calculation. Scale is an expression that returns a Double, or of a type that can be implicitly converted to Double. -

Performance Attribution from Bacon

Performance Attribution from Bacon Matthieu Lestel February 5, 2020 Abstract This vignette gives a brief overview of the functions developed in Bacon(2008) to evaluate the performance and risk of portfolios that are included in PerformanceAn- alytics and how to use them. There are some tables at the end which give a quick overview of similar functions. The page number next to each function is the location of the function in Bacon(2008) Contents 1 Risk Measure 3 1.1 Mean absolute deviation (p.62) . 3 1.2 Frequency(p.64) ................................ 3 1.3 SharpeRatio(p.64)............................... 4 1.4 Risk-adjusted return: MSquared (p.67) . 4 1.5 MSquared Excess (p.68) . 4 2 Regression analysis 5 2.1 Regression equation (p.71) . 5 2.2 Regression alpha (p.71) . 5 2.3 Regression beta (p.71) . 5 2.4 Regression epsilon (p.71) . 6 2.5 Jensen'salpha(p.72) .............................. 6 2.6 SystematicRisk(p.75) ............................. 6 2.7 SpecificRisk(p.75)............................... 7 2.8 TotalRisk(p.75) ................................ 7 2.9 Treynorratio(p.75)............................... 7 2.10 Modified Treynor ratio (p.77) . 7 2.11 Appraisal ratio (or Treynor-Black ratio) (p.77) . 8 2.12 Modified Jensen (p.77) . 8 1 2.13 Fama decomposition (p.77) . 8 2.14 Selectivity (p.78) . 9 2.15 Net selectivity (p.78) . 9 3 Relative Risk 9 3.1 Trackingerror(p.78) .............................. 9 3.2 Information ratio (p.80) . 10 4 Return Distribution 10 4.1 Skewness (p.83) . 10 4.2 Sample skewness (p.84) . 10 4.3 Kurtosis(p.84) ................................ -

ESG and Risk-Adjusted Performance

ESG and risk-adjusted performance An empirical and comparative analysis on ESG-fund performance relative to their conventional counterparts in Scandinavia Cassandra Myhre Master’s Thesis University of Oslo Department of Economics Supervisor: Jin Cao Date: May, 2021 Preface This thesis marks the end of my Master’s degree in Economics at the University of Oslo. I want to thank my supervisor, Jin Cao, for his excellent support and guidance throughout the process. I would also like to thank finance major, Edmundas Lapenas, for his invaluable insight in financial data analysis. Our many in-depth discussions have made this thesis possible. I hope that my humble contribution in analysing the ESG effects on risk-adjusted returns in the Scandinavian market will be considered as a valuable source and incentive for further research in this field. Cassandra Myhre, May 2020 Abstract There is an accepted principle in the financial industry that the bigger the risk, the higher the potential reward. The introduction of sustainability in the investment equation has however revolutionised the risk-return tradeoff. Not only with regards to creating value but also because it has ruptured the misconception that responsible funds provide lower returns. Companies who have incorporated Environmental, Social and Fair Governance (ESG) factors into their investment portfolios have shown lower volatility compared to their peers in the same industry. Furthermore, numerous studies have shown that ESG also generated higher returns in the long run, meaning that not only does it potentially minimise risk, but it is also a more profitable choice. In this paper I will conduct an empirical and comparative study of the risk-return tradeoff where I will analyse ESG funds and conventional funds based in Scandinavia, with a sample developed specially for this thesis. -

Risk Measures in Quantitative Finance

Risk Measures in Quantitative Finance by Sovan Mitra Abstract This paper was presented and written for two seminars: a national UK University Risk Conference and a Risk Management industry workshop. The target audience is therefore a cross section of Academics and industry professionals. The current ongoing global credit crunch 1 has highlighted the importance of risk measurement in Finance to companies and regulators alike. Despite risk measurement’s central importance to risk management, few papers exist reviewing them or following their evolution from its foremost beginnings up to the present day risk measures. This paper reviews the most important portfolio risk measures in Financial Math- ematics, from Bernoulli (1738) to Markowitz’s Portfolio Theory, to the presently pre- ferred risk measures such as CVaR (conditional Value at Risk). We provide a chrono- logical review of the risk measures and survey less commonly known risk measures e.g. Treynor ratio. Key words: Risk measures, coherent, risk management, portfolios, investment. 1. Introduction and Outline arXiv:0904.0870v1 [q-fin.RM] 6 Apr 2009 Investors are constantly faced with a trade-off between adjusting potential returns for higher risk. However the events of the current ongoing global credit crisis and past financial crises (see for instance [Sto99a] and [Mit06]) have demonstrated the necessity for adequate risk measurement. Poor risk measurement can result in bankruptcies and threaten collapses of an entire finance sector [KH05]. Risk measurement is vital to trading in the multi-trillion dollar derivatives industry [Sto99b] and insufficient risk analysis can misprice derivatives [GF99]. Additionally 1“Risk comes from not knowing what you’re doing”, Warren Buffett. -

Performance Evaluation of Size, Book-To-Market and Momentum Portfolios

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect Procedia Economics and Finance 14 ( 2014 ) 481 – 490 International Conference on Applied Economics (ICOAE) 2014 Performance Evaluation of Size, Book-to-Market and Momentum Portfolios Sotiria Plastira* University of Piraeus, Department of Statistics & Insurance Science, 80 Karaoli & Dimitriou Str., 18534 Piraeus, Greece Abstract This article provides an extensive review on traditional and more sophisticated evaluation measures focusing on premium returns adjusted for the associated risk. The implementation of these performance measures on the HML, SMB, MOM, LT-Rev and ST-Rev empirical factors produces for first time a ranking of the aforementioned portfolios, revealing that the HML and MOM factor portfolios achieve the best and worst performance, respectively. This analysis goes one step further by implementing the same performance measures on portfolios formed by a specific characteristic, such as size, book-to-market or momentum, establishing thus a connection between these characteristics and portfolios’ performance. Our empirical findings suggest that the traditional and downside performance measures lead to identical rankings, whereas drawdown-based ones influence the rank order among the portfolios of interest. ©© 2014 2014 The The Authors. Authors. Published Published by Elsevierby Elsevier B.V. B.V. This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/). Selection and/or peer-review under responsibility of the Organising Committee of ICOAE 2014. Selection and/or peer-review under responsibility of the Organizing Committee of ICOAE 2014 Key Words: Risk measures; Performance measures; Portfolio ranking; Fama/French factors.