GLOSSARY of PHILOSOPHICAL TERMS Z

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Discovering Semantic Links Between Synonyms, Hyponyms and Hypernyms Ricardo Avila, Gabriel Lopes, Vania Vidal, Jose Macedo

World Academy of Science, Engineering and Technology International Journal of Computer and Systems Engineering Vol:13, No:6, 2019 Discovering Semantic Links Between Synonyms, Hyponyms and Hypernyms Ricardo Avila, Gabriel Lopes, Vania Vidal, Jose Macedo Abstract—This proposal aims for semantic enrichment between Other approaches have been proposed to identify such glossaries using the Simple Knowledge Organization System (SKOS) mappings (see Section IV), but they are still far from perfect. vocabulary to discover synonyms, hyponyms and hyperonyms In general, previous studies have tried to directly identify semiautomatically, in Brazilian Portuguese, generating new semantic relationships based on WordNet. To evaluate the quality of this different types of relationships, usually with the help of proposed model, experiments were performed by the use of two sets dictionaries such as WordNet. On the other hand, we propose containing new relations, being one generated automatically and the an enrichment strategy using a two-step approach. In the first other manually mapped by the domain expert. The applied evaluation step, we apply the use of a crawler to collect synonyms, metrics were precision, recall, f-score, and confidence interval. The hyponyms, and hyperonyms to generate an XML file, then results obtained demonstrate that the applied method in the field of Oil Production and Extraction (E&P) is effective, which suggests that we generate new relationships between the instances and it can be used to improve the quality of terminological mappings. determine the initial ontology mapping with approximate The procedure, although adding complexity in its elaboration, can be matches of equality. Then, using a unified lexical ontology reproduced in others domains. -

Training's Ability to Improve Other Race Individuation

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies, Jack N. Averitt College of Spring 2013 Recognizing the Other: Training's Ability to Improve Other Race Individuation W. Grady Rose Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/etd Part of the Psychology Commons, and the Race and Ethnicity Commons Recommended Citation Rose, W. Grady, "Recognizing the Other: Training's Ability to Improve Other Race Individuation" (2013). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 47. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/etd/47 This thesis (open access) is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies, Jack N. Averitt College of at Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Running head: RECOGNIZING THE OTHER 1 RECOGNIZING THE OTHER: TRAINING’S ABILITY TO IMPROVE OTHER RACE INDIVIDUATION by W. GRADY ROSE (Under the Direction of Amy Hackney, Ph. D.) ABSTRACT Members of one race or ethnicity are less able to individuate members of another race compared to their own race peers. This phenomenon is known as the other race effect (ORE) or the cross race effect (CRE). Not only are individuals less able to identify members of the other race but they are also more likely to pick those individuals out of a crowd. The categorization- individuation model predicts that this deficit arises from a lack of motivated individuation; in which members of the other race are remembered at the category level as a prototype while own race members are remembered by name with individual characteristics. -

The Black Platonism of David Lindsay

Volume 19 Number 2 Article 3 Spring 3-15-1993 Encounter Darkness: The Black Platonism of David Lindsay Adelheid Kegler Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Kegler, Adelheid (1993) "Encounter Darkness: The Black Platonism of David Lindsay," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 19 : No. 2 , Article 3. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol19/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract Characterizes Lindsay as a “belated symbolist” whose characters are “personifications of ontological values.” Uses Neoplatonic “references to transcendence” but his imagery and technique do not suggest a positive view of transcendence. Additional Keywords Lindsay, David—Neoplatonism; Lindsay, David—Philosophy; Lindsay, David. A Voyage to Arcturus; Neoplatonism in David Lindsay This article is available in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. -

Philosophical Theory-Construction and the Self-Image of Philosophy

Open Journal of Philosophy, 2014, 4, 231-243 Published Online August 2014 in SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/ojpp http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ojpp.2014.43031 Philosophical Theory-Construction and the Self-Image of Philosophy Niels Skovgaard Olsen Department of Philosophy, University of Konstanz, Konstanz, Germany Email: [email protected] Received 25 May 2014; revised 28 June 2014; accepted 10 July 2014 Copyright © 2014 by author and Scientific Research Publishing Inc. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY). http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Abstract This article takes its point of departure in a criticism of the views on meta-philosophy of P.M.S. Hacker for being too dismissive of the possibility of philosophical theory-construction. But its real aim is to put forward an explanatory hypothesis for the lack of a body of established truths and universal research programs in philosophy along with the outline of a positive account of what philosophical theories are and of how to assess them. A corollary of the present account is that it allows us to account for the objective dimension of philosophical discourse without taking re- course to the problematic idea of there being worldly facts that function as truth-makers for phi- losophical claims. Keywords Meta-Philosophy, Hacker, Williamson, Philosophical Theories 1. Introduction The aim of this article is to use a critical discussion of the self-image of philosophy presented by P. M. S. Hacker as a platform for presenting an alternative, which offers an account of how to think about the purpose and cha- racter of philosophical theories. -

Denying a Dualism: Goodman's Repudiation of the Analytic/Synthetic Distinction

Midwest Studies in Philosophy, 28, 2004, 226-238. Denying a Dualism: Goodman’s Repudiation of the Analytic/Synthetic Distinction Catherine Z. Elgin The analytic synthetic/distinction forms the backbone of much modern Western philosophy. It underwrites a conception of the relation of representations to reality which affords an understanding of cognition. Its repudiation thus requires a fundamental reconception and perhaps a radical revision of philosophy. Many philosophers believe that the repudiation of the analytic/synthetic distinction and kindred dualisms constitutes a major loss, possibly even an irrecoverable loss, for philosophy. Nelson Goodman thinks otherwise. He believes that it liberates philosophy from unwarranted restrictions, creating opportunities for the development of powerful new approaches to and reconceptions of seemingly intractable problems. In this article I want to sketch some of the consequences of Goodman’s reconception. My focus is not on Goodman’s reasons for denying the dualism, but on some of the ways its absence affects his position. I do not contend that the Goodman obsessed over the issue. I have no reason to think that the repudiation of the distinction was a central factor in his intellectual life. But by considering the function that the analytic/synthetic distinction has performed in traditional philosophy, and appreciating what is lost and gained in repudiating it, we gain insight into Goodman’s contributions. I begin then by reviewing the distinction and the conception of philosophy it supports. The analytic/synthetic distinction is a distinction between truths that depend entirely on meaning and truths that depend on both meaning and fact. In the early modern period, it was cast as a distinction between relations of ideas and matters of fact. -

God As Both Ideal and Real Being in the Aristotelian Metaphysics

God As Both Ideal and Real Being In the Aristotelian Metaphysics Martin J. Henn St. Mary College Aristotle asserts in Metaphysics r, 1003a21ff. that "there exists a science which theorizes on Being insofar as Being, and on those attributes which belong to it in virtue of its own nature."' In order that we may discover the nature of Being Aristotle tells us that we must first recognize that the term "Being" is spoken in many ways, but always in relation to a certain unitary nature, and not homonymously (cf. Met. r, 1003a33-4). Beings share the same name "eovta," yet they are not homonyms, for their Being is one and the same, not manifold and diverse. Nor are beings synonyms, for synonymy is sameness of name among things belonging to the same genus (as, say, a man and an ox are both called "animal"), and Being is no genus. Furthermore, synonyms are things sharing a common intrinsic nature. But things are called "beings" precisely because they share a common relation to some one extrinsic nature. Thus, beings are neither homonyms nor synonyms, yet their core essence, i.e. their Being as such, is one and the same. Thus, the unitary Being of beings must rest in some unifying nature extrinsic to their respective specific essences. Aristotle's dialectical investigations into Being eventually lead us to this extrinsic nature in Book A, i.e. to God, the primary Essence beyond all specific essences. In the pre-lambda books of the Metaphysics, however, this extrinsic nature remains very much up for grabs. -

The Universe, Life and Everything…

Our current understanding of our world is nearly 350 years old. Durston It stems from the ideas of Descartes and Newton and has brought us many great things, including modern science and & increases in wealth, health and everyday living standards. Baggerman Furthermore, it is so engrained in our daily lives that we have forgotten it is a paradigm, not fact. However, there are some problems with it: first, there is no satisfactory explanation for why we have consciousness and experience meaning in our The lives. Second, modern-day physics tells us that observations Universe, depend on characteristics of the observer at the large, cosmic Dialogues on and small, subatomic scales. Third, the ongoing humanitarian and environmental crises show us that our world is vastly The interconnected. Our understanding of reality is expanding to Universe, incorporate these issues. In The Universe, Life and Everything... our Changing Dialogues on our Changing Understanding of Reality, some of the scholars at the forefront of this change discuss the direction it is taking and its urgency. Life Understanding Life and and Sarah Durston is Professor of Developmental Disorders of the Brain at the University Medical Centre Utrecht, and was at the Everything of Reality Netherlands Institute for Advanced Study in 2016/2017. Ton Baggerman is an economic psychologist and psychotherapist in Tilburg. Everything ISBN978-94-629-8740-1 AUP.nl 9789462 987401 Sarah Durston and Ton Baggerman The Universe, Life and Everything… The Universe, Life and Everything… Dialogues on our Changing Understanding of Reality Sarah Durston and Ton Baggerman AUP Contact information for authors Sarah Durston: [email protected] Ton Baggerman: [email protected] Cover design: Suzan Beijer grafisch ontwerp, Amersfoort Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout Amsterdam University Press English-language titles are distributed in the US and Canada by the University of Chicago Press. -

Philosophical Logic 2018 Course Description (Tentative) January 15, 2018

Philosophical Logic 2018 Course description (tentative) January 15, 2018 Valentin Goranko Introduction This 7.5 hp course is mainly intended for students in philosophy and is generally accessible to a broad audience with basic background on formal classical logic and general appreciation of philosophical aspects of logic. Practical information The course will be given in English. It will comprise 18 two-hour long sessions combining lectures and exercises, grouped in 2 sessions per week over 9 teaching weeks. The weekly pairs of 2-hour time slots (incl. short breaks) allocated for these sessions, will be on Mondays during 10.00-12.00 and 13.00-15.00, except for the first lecture. The course will begin on Wednesday, April 4, 2018 (Week 14) at 10.00 am in D220, S¨odra huset, hus D. Lecturer's info: Name: Valentin Goranko Email: [email protected] Homepage: http://www2.philosophy.su.se/goranko Course webpage: http://www2.philosophy.su.se/goranko/Courses2018/PhilLogic-2018.html Prerequisites The course will be accessible to a broad audience with introductory background on classical formal logic. Some basic knowledge of modal logics would be an advantage but not a prerequisite. Brief description Philosophical logic studies a variety of non-classical logical systems intended to formalise and reason about various philosophical concepts and ideas. They include a broad family of modal logics, as well as many- valued, intuitionistic, relevant, conditional, non-monotonic, para-consistent, etc. logics. Modal logics extend classical logic with additional intensional logical operators, reflecting different modes of truth, including alethic, epistemic, doxastic, temporal, deontic, agentive, etc. -

Affect, Trust, and Dignity: Ontological Possibilities and Material Consequences for a Philosophy of Educational Resonance Walter Gershon Kent State University

Walter Gershon 461 Affect, Trust, and Dignity: Ontological Possibilities and Material Consequences for a Philosophy of Educational Resonance Walter Gershon Kent State University INTRODUCTION This essay articulates a philosophy of resonance in education, from some of its theoretical possibilities through their material consequences. Contemporary under- standings in educational philosophy have a tendency to utilize ocular metaphors, epistemological constructions that provide frames for seeing the world. There are at least the following three difficulties with such a reliance on the ocular. First, they are easily interrupted by nonocular metaphors. While this may seem to be a rather surface concern, it points to a deep philosophical set of problems. For example, what happens when the augenblick, a construct around which much philosophizing has been accomplished, is pressed slightly to become a “blink of an ear”?1 This move not only questions the veracity of ocular-centric constructions from blinks to texts — for what does it say about an idea if it falls apart by shifting senses — but it also presses at the feasibility of framing, its inherently bounded nature as well as the large number of possibilities excluded by its gaze. Second, the sonic provides another avenue for wonder. Sound is omnipresent and questions of hearing or listening are as much about physical anatomy as they concern sociocultural constructs about what sounds can mean. Unlike sight that is necessarily directional and constantly interrupted (for example, by blinking), sound is omnidirectional, creating a context in which focus requires a particular kind of attentive filtering rather than a reframing or panning directionality. Finally, sound is and always has been. -

Arguments Vs. Explanations

Arguments vs. Explanations Arguments and explanations share a lot of common features. In fact, it can be hard to tell the difference between them if you look just at the structure. Sometimes, the exact same structure can function as an argument or as an explanation depending on the context. At the same time, arguments are very different in terms of what they try to accomplish. Explaining and arguing are very different activities even though they use the same types of structures. In a similar vein, building something and taking it apart are two very different activities, but we typically use the same tools for both. Arguments and explanations both have a single sentence as their primary focus. In an argument, we call that sentence the “conclusion”, it’s what’s being argued for. In an explanation, that sentence is called the “explanandum”, it’s what’s being explained. All of the other sentences in an argument or explanation are focused on the conclusion or explanandum. In an argument, these other sentences are called “premises” and they provide basic reasons for thinking that the conclusion is true. In an explanation, these other sentences are called the “explanans” and provide information about how or why the explanandum is true. So in both cases we have a bunch of sentences all focused on one single sentence. That’s why it’s easy to confuse arguments and explanations, they have a similar structure. Premises/Explanans Conclusion/Explanandum What is an argument? An argument is an attempt to provide support for a claim. One useful way of thinking about this is that an argument is, at least potentially, something that could be used to persuade someone about the truth of the argument’s conclusion. -

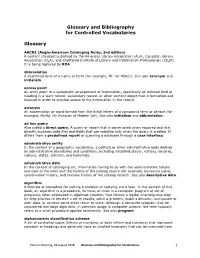

Glossary and Bibliography for Vocabularies 1 the Codes (For Example, the Dewey Decimal System Number 735.942)

Glossary and Bibliography for Controlled Vocabularies Glossary AACR2 (Anglo-American Cataloging Rules, 2nd edition) A content standard published by the American Library Association (ALA), Canadian Library Association (CLA), and Chartered Institute of Library and Information Professionals (CILIP). It is being replaced by RDA. abbreviation A shortened form of a name or term (for example, Mr. for Mister). See also acronym and initialism. access point An entry point to a systematic arrangement of information, specifically an indexed field or heading in a work record, vocabulary record, or other content object that is formatted and indexed in order to provide access to the information in the record. acronym An abbreviation or word formed from the initial letters of a compound term or phrase (for example, MoMA, for Museum of Modern Art). See also initialism and abbreviation. ad hoc query Also called a direct query. A query or report that is constructed when required and that directly accesses data files and fields that are selected only when the query is created. It differs from a predefined report or querying a database through a user interface. administrative entity In the context of a geographic vocabulary, a political or other administrative body defined by administrative boundaries and conditions, including inhabited places, nations, empires, nations, states, districts, and townships. administrative data In the context of cataloging art, information having to do with the administrative history and care of the work and the history of the catalog record (for example, insurance value, conservation history, and revision history of the catalog record). See also descriptive data. algorithm A formula or procedure for solving a problem or carrying out a task. -

Authority, Authoritarianism, and Education

"Hybrid with Projection #1 by Susan Hetmannsperger 17 Authority, Authoritarianism, and Education Bruce Romanish The achievement of political freedom in a democratic produced populations desirous of and supportive of such system results from the conscious plans and actions of a political leadership since various environmental causes are human community. Once political freedom is identified as as significant in explaining authoritarianism as are psycho- an aim, the true task inheres in developing social structures logical predispositions.1 This issue has been addressed as and institutional frameworks which create, nurture, and well in terms of personality development, family influences, sustain that end. These structures and frameworks themselves and from the standpoint of the effects of religions and are in need of care and support if the democracy they nourish religious movements, but scant attention has been paid to the is not to wither and atrophy from neglect. Yet desiring politi- school's role as a shaper of patterns of belief, conduct, and cal freedom, accomplishing it, and maintaining it do not come ways of thinking in relationship to authoritarianism. with instructions. Modern history provides many examples If schools exhibit democratic characteristics, that may of societies that lost their way and slipped into the darkness reflect democratic features of the larger social order or the and despair of political oppression. schools are making a contribution to society's movement in This essay examines the concept of authoritarianism and that direction. Conversely, an authoritarian experience in the ways it is reflected and fostered in school life and school school life suggests either a broader cultural authoritarianism structure.