AGRICULTURAL PRODUCTION Z 0 AU-Weather Roods

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Onchocerdasts Corurot Pto·Gii'ammc •N West Afri:Ca Prog.Ra.Mme De Luuc Contrc Ronchocercose En Afrique De I'oues't

Onchocerdasts Corurot Pto·gii'ammc •n West Afri:ca Prog.ra.mme de Luuc contrc rOnchocercose en Afrique de I'Oues't OCP/EAC/92.1 ORIGINAL: ENGLISH EXPERT ADVISORY COMMITTEE Report of the thirteenth session Ouagadougou. 8- 12 June 1992 Contents List of Participants. 2 Executive Summary and Recommendations . 4 A. Opening of the session .................................................. 7 B. Adoption of the agenda ·................................................. 8 C. Follow-up of EAC.12 recommendations ..................................... 8 D. Matters arising from the twelfth session of th'e JPC ............................ 8 E. Administrative and financial briefing . 9 F. Vector control operations ............................................... 10 G. Report of the thirteenth session of the Ecological Group ....................... 13 H. Epidemiological activities and treatment . 16 I. Onchocerciasis Chemotherapy Project (OCT/Macrofil) . 20 J. Devolution ......................................................... 21 K. Research . 24 L. Other matters . • . 26 M. Date and place of EAC.14 .............................................. 26 N. Adoption of the draft report ............................................. 27 0. Closure of the session ........................ : . ........................ 27 Annex 1: Report of the thirteenth session of the Ecological Group . 28 . JPCI3.3 (OCP/EAC/92.1) Page 2 LIST OF PARTICIPANTS Members Dr Y. Aboagye-Atta, Resident Medical Officer, Department of Health and Nuclear Medicine, Ghana Atomic Energy Commission, P.O. Box 80, .I..&&.Qn., Accra, Ghana Dr A.D.M. Bryceson, Hospital for Tropical Diseases, 4 St. Pancras Way, London, NWI OPE, United Kingdom ~ Professor D. Calamari, Istituto di Entomologia Agraria, Universiui degli Studi di Milano, Via Celoria 2, 1-20133 Milano, Italy Professor J. Diallo, 51 Corniche Fleurie-La-Roseraie, 06200 Nice, France Dr A .D. Franklin, 14 Impasse de Ia Cave, 77100 Meaux, France Professor T.A. -

Assessing Floods and Droughts in the Mékrou River Basin (West Africa): A

Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. Discuss., https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-2017-195 Manuscript under review for journal Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. Discussion started: 20 June 2017 c Author(s) 2017. CC BY 3.0 License. Assessing floods and droughts in the Mékrou River Basin (West Africa): A combined household survey and climatic trends analysis approach Vasileios Markantonis1, Fabio Farinosi1, Celine Dondeynaz1, Iban Ameztoy1, Marco Pastori1, Luca Marletta1, 5 Abdou Ali2, Cesar Carmona Moreno1 1 European Commission, DG Joint Research Centre, Ispra, Italy 2 AgrHyMet, Niamey, Niger Correspondence to: Vasileios Markantonis ([email protected]) Abstract. The assessment of natural hazards such as floods and droughts is a complex issue demanding integrated approaches 10 and high quality data. Especially in African developing countries, where information is limited, the assessment of floods and droughts, though an overarching issue influencing economic and social development, is even more challenging. This paper presents an integrated approach to assess crucial aspects of floods and droughts in the transboundary Mekrou River basin (a portion of the Niger basin in West Africa) combining climatic trends analysis and the findings of a household survey. The multi-variables trend analysis estimates at the biophysical level the climate variability and the occurrence of floods and 15 droughts. These results are coupled with the analysis of household survey data that reveal behaviors and opinions of the local residents regarding the observed climate variability and occurrence of flood and drought events, household mitigation measures and impacts of floods and droughts. Furthermore, two econometric models are set up to estimate the costs of floods and droughts of impacted households during a two years period (2014-2015) resulting into an average cost of approximately 495 euro per household for floods and 391 euro per household for droughts. -

The New Frontier for Jihadist Groups?

Promediation North of the countries of the Gulf of Guinea The new frontier for jihadist groups? www.kas.de North of the countries of the Gulf of Guinea The new frontier for jihadist groups? At a glance At a glance tion has led to increased competition for access to However, these efforts are still not enough. In natural resources and to rising tensions between addition to operational or material flaws in the several communities. security network, there is also a weakness in terms of political and military doctrine. Since In 2020, armed jihadist groups in Sahel faced the authorities believe that the unrest on their Burkina Faso’s southern border is also of inter- jihadist insurgencies have developed in the increased pressure in their strongholds in Mali, northern borders will eventually spill over into est to the jihadists because it is a very profitable Sahara- Sahel region, no state has yet found an Niger and Burkina. their territory. No attacks have yet been carried area for all kinds of trafficking. Both to the east adequate response to contain them. Priority is out on Beninese soil, but incursions by suspected and west, this border has been known for several given to the fight against terrorism, often to the While the Support Group for Islam and Muslims jihadists are on the increase. Côte d’Ivoire was years as an epicentre for the illicit trade in arms, detriment of dialogue with communities and the (JNIM) and the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara first attacked in the north in June 2020. Jihadists gold, drugs, ivory, or goods such as cigarettes and search for local solutions. -

World Heritage 28 COM

World Heritage 28 COM Distribution limited WHC-04/28.COM/6 Paris, 15 April 2004 Original: English/French UNITED NATIONS EDUCATIONAL, SCIENTIFIC AND CULTURAL ORGANIZATION CONVENTION CONCERNING THE PROTECTION OF THE WORLD CULTURAL AND NATURAL HERITAGE WORLD HERITAGE COMMITTEE Twenty-eighth session Suzhou, China 28 June – 7 July 2004 Item 6 of the Provisional Agenda: Decisions adopted by the 27th session of the World Heritage Committee (Paris, 30 June - 5 July 2003) World Heritage 27 COM Distribution limited WHC-03/27.COM/24 Paris, 10 December 2003 Original: English/French UNITED NATIONS EDUCATIONAL, SCIENTIFIC AND CULTURAL ORGANIZATION CONVENTION CONCERNING THE PROTECTION OF THE WORLD CULTURAL AND NATURAL HERITAGE WORLD HERITAGE COMMITTEE Twenty-seventh session Paris, UNESCO Headquarters, Room XII 30 June – 5 July 2003 DECISIONS ADOPTED BY THE 27TH SESSION OF THE WORLD HERITAGE COMMITTEE IN 2003 Published on behalf of the World Heritage Committee by: UNESCO World Heritage Centre 7, place de Fontenoy 75352 Paris 07 SP France Tel: +33 (0)1 4568 1571 Fax: +33(0)1 4568 5570 E-mail: [email protected] http://whc.unesco.org/ This report is available in English and French at the following addresses: http://whc.unesco.org/archive/decrec03.htm (English) http://whc.unesco.org/fr/archive/decrec03.htm (French) Second Printing, March 2004 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page No. 1 Opening Session 1 2 Adoption of the agenda and the timetable 2 3 Election of the Chairperson, Vice-Chairpersons and Rapporteur 3 4 Report of the Rapporteur on the 6th extraordinary session -

Biodiversity in Sub-Saharan Africa and Its Islands Conservation, Management and Sustainable Use

Biodiversity in Sub-Saharan Africa and its Islands Conservation, Management and Sustainable Use Occasional Papers of the IUCN Species Survival Commission No. 6 IUCN - The World Conservation Union IUCN Species Survival Commission Role of the SSC The Species Survival Commission (SSC) is IUCN's primary source of the 4. To provide advice, information, and expertise to the Secretariat of the scientific and technical information required for the maintenance of biologi- Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna cal diversity through the conservation of endangered and vulnerable species and Flora (CITES) and other international agreements affecting conser- of fauna and flora, whilst recommending and promoting measures for their vation of species or biological diversity. conservation, and for the management of other species of conservation con- cern. Its objective is to mobilize action to prevent the extinction of species, 5. To carry out specific tasks on behalf of the Union, including: sub-species and discrete populations of fauna and flora, thereby not only maintaining biological diversity but improving the status of endangered and • coordination of a programme of activities for the conservation of bio- vulnerable species. logical diversity within the framework of the IUCN Conservation Programme. Objectives of the SSC • promotion of the maintenance of biological diversity by monitoring 1. To participate in the further development, promotion and implementation the status of species and populations of conservation concern. of the World Conservation Strategy; to advise on the development of IUCN's Conservation Programme; to support the implementation of the • development and review of conservation action plans and priorities Programme' and to assist in the development, screening, and monitoring for species and their populations. -

PNAAJ203.Pdf

PN-MJ203 EDa-000-C 212 'Draft enviromnental report on Niger Speece, Mark Ariz. Univ. Office of Arid Lands Studies 6. IXOCUMVT DATE (110) )7.NJMDER OF1 P. (125) II. R NIR,(175) 19801 166p. NG330.96626. S742 9. EFERENZE ORGANIZATIUN (150) Ariz. 10. SUPLMENTAiY Na1M (500) (Sponsored by AID through the U. S. National Committee for Man and the Biosphere) 11. ABSTRACT (950) 12. D SCKWrOR5 (o20) ,. ?mj3Cr N (iS5 ' Niger Enviironmental factors Soil erosion 931015900 Desertification Deforestation 14. WRiA .414.) IL Natural resources Water resources Water supply Droughts AID/ta-G-11t1 wnmiwommmr 4, NG6 sq~DRAFT ErWIROHIITAL REPORT ON NIGER prepared by the Arid Lands Information Center Office of Arid Lands Studies University of Arizona Tucson, Arizona 85721 ,National Park Service Contract No. CX-0001-0-0003 with U.S. Man and the Biosphere Secretariat Department of Stati Washington, D.C. Septmber 1980 2.0 Hmtu a ReOe$4 , 9 2.1 OU6era Iesources and Energy 9 2. 1.1",Mineral Policy 11 2.1.2 Ainergy 12 2.2 Water 13 2.2.1 Surface Water 13 2.2.2 Groundwater I: 2.2.3 Water Use 16 2.2.4 Water Law 17 2.3 Soils and Agricultural Land Use 18 2.3.1 Soils 18 2.3.2 Agriculture 23 2.4 Vegetation 27 2.4.1 Forestry 32 2.4.2 Pastoralism 33 2.5 Fau, and Protected Areas 36 2.5.1 Endangered Species 38 2.5.2 Fishing 38 3.0 Major Environmental Problems 39 3.1 Drouqht 39 3.2 Desertification 40 3.3 Deforestation and Devegetation 42 3.4 Soil Erosion and Degradation 42 3.5 Water 43 4.0 Development 45 Literature Cited 47 Appendix I Geography 53 Appendix II Demographic Characteristics 61 Appendix III Economic Characteristics 77 Appendi" IV List of U.S. -

Senegalese Grasshoppers: Localized Infestations in Niger from Northeastern Niamey Departement Over to Maradi Departement

Report Number 13 July 1987 FEWS Country Report NIGER Africa Bureau U.S. Agency for International Development YAP 1: NIGER Summary Map LIBYA ALGERI A Agadez Rainfall Deficit through 2nd decade As of MLy st oveal level of June Af0 st v,' of vegetation was above tL.attLae of 1986, and the average for 1982-66. As of June 20th, levels were st ll generally higher than // •. .. ... ..,.. -.. .. BEN I BENINNIGERIA Senegalese Grasshoppers: Localized infestations in Niger from northeastern Niamey Departement over to Maradi Departement. Very heavy infestations in Nigeria will likely move northward as rains advance into Niger. FEWSiPWA Famine Early Warning System Country Report NIGER The Rains Begin Prepared for the Africa Bureau of the U.S. Agency for International Development Prepared by Price, Williams & Associates, Inc. July 1987 Contents Page i Introduction 1 Summary 1 Meteorology 4 Vegetation Levels 9 Grasshoppers and Locusts List of Figures PaeC 2 Figure 1 Meteorology 3 Figure 2 Niger NVI Trends by Department 5 Figure 3 NVI Trends - Niamey Department 5 Figure 4 NVI Trends - Dosso Departmcnt 6 Figure 5 NVI Trends - Tahoua Department 7 Figure 6 NVI Trends - Maradi Department 7 Figure 7 NVI Trends - Zinder Department 8 Figure 8 NVI Trends - Diffa Department 9 Figure 9 NVI Trends - Agadez Department 10 Figure 10 Hatching Senegalese Grasshoppers Back Cover Map 2 Niger Reference Map INTRODUCTION This is the thirteenth in a series of monthly reports on Niger issued by the Famine Early Warning System (FEWS). It is designed to provide decisionmakers with current information and analysis on existing and potential nutrition emergency situations. -

Assessment of Chronic Food Insecurity in Niger

Assessment of Chronic Food Insecurity in Niger Analysis Coordination March 2019 Assessment of Chronic Food Insecurity in Niger 2019 About FEWS NET Created in response to the 1984 famines in East and West Africa, the Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET) provides early warning and integrated, forward-looking analysis of the many factors that contribute to food insecurity. FEWS NET aims to inform decision makers and contribute to their emergency response planning; support partners in conducting early warning analysis and forecasting; and provide technical assistance to partner-led initiatives. To learn more about the FEWS NET project, please visit www.fews.net. Acknowledgements This publication was prepared under the United States Agency for International Development Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET) Indefinite Quantity Contract, AID-OAA-I-12-00006. The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. Recommended Citation FEWS NET. 2019. Assessment of Chronic Food Insecurity in Niger. Washington, DC: FEWS NET. Famine Early Warning Systems Network ii Assessment of Chronic Food Insecurity in Niger 2019 Table of Contents Executive Summary ..................................................................................................................................................................... 1 Background ............................................................................................................................................................................. -

Mise En Page 1

N°21 - December 2016 MEKROU PROJECT - SIGNIFICANT PROGRESS IN THE IMPLEMENTATION - GOOD APPRECIATION OF STAKEHOLDERS Let's discover... the Water Museum in Burkina Faso Special issue on “Mekrou Project” “Water for Growth and Poverty Reduction Content ADVISORY COMMITTEE Pages EDITOR ’S WORD MEKROU PROJECT : Water for growth and poverty reduction 3 2016 A DVISORY COMMITTEE MEETING SESSION Mekrou Project Coordination Global Advisory Committee Meeting in Cotonou 4 THE FRAMEWORK AGREEMENT The Advisory Committee updates on the progress 5 MID -TERM PROJECT ASSESSMENT Analytical narrative of the project implementation 6 Pilot Projects 12 SIGNING THE FRAMEWORK AGREEMENT Promoting the political dialogue for the joint management of the natural resources of the Mékrou Basin 14 LET'S DISCOVER ... What do the various stakeholders think of the Mekrou project and its mid-term results? 16 LET 'S DISCOVER ... THE WATER MUSEUM : A sanctuary for the development of the water resource 21 Running Water N°21 - December 2016 Running Water N°19 - December 2014 2 “Water for Growth and Poverty Reduction BeNiN - B uRkiNa FaSo - N iGeR in the Mekrou Transboundary Basin” Editor’s word Mekrou Project Water for growth and poverty reduction roject management is a thrilling tions in relation to the concrete results thing when despite difficulties you of the Project. P feel that things are progressing numerous studies have been carried and reaching out to results. The project out and validated in each country and «Water for growth and poverty reduc - the data collected are being integrated tion in the Mekrou transboundary to serve as a basis for the different sce - basin» has demonstrated to be a real narios to build the models that will be tool for cross-border integration and proposed as decision-making tools. -

Multihazard Risk Assessment for Planning with Climate in the Dosso Region, Niger

climate Article Multihazard Risk Assessment for Planning with Climate in the Dosso Region, Niger Maurizio Tiepolo 1,* ID , Maurizio Bacci 1,2 ID and Sarah Braccio 1 1 Interuniversity Department of Regional and Urban Studies and Planning (DIST), Politecnico and University of Turin, Viale G. Mattioli 39, 10125 Torino, Italy; [email protected] or [email protected] (M.B.); [email protected] (S.B.) 2 Ibimet CNR, Via G. Caproni 8, 50145 Florence, Italy * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +39-011-090-7491 Received: 13 July 2018; Accepted: 6 August 2018; Published: 8 August 2018 Abstract: International aid for climate change adaptation in West Africa is increasing exponentially, but our understanding of hydroclimatic risks is not keeping pace with that increase. The aim of this article is to develop a multihazard risk assessment on a regional scale based on existing information that can be repeated over time and space and that will be useful during decision-making processes. This assessment was conducted in Dosso (Niger), the region most hit by flooding in the country, with the highest hydroclimatic risk in West Africa. The assessment characterizes the climate, identifies hazards, and analyzes multihazard risk over the 2011–2017 period for each of the region’s 43 municipalities. Hazards and risk level are compared to the intervention areas and actions of 6 municipal development plans and 12 adaptation and resilience projects. Over the past seven years, heavy precipitation and dry spells in the Dosso region have been more frequent than during the previous 30-year period. As many as 606 settlements have been repeatedly hit and 15 municipalities are classified as being at elevated-to-severe multihazard risk. -

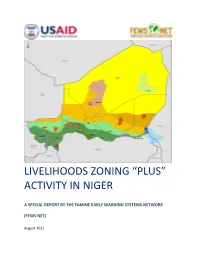

Livelihoods Zoning “Plus” Activity in Niger

LIVELIHOODS ZONING “PLUS” ACTIVITY IN NIGER A SPECIAL REPORT BY THE FAMINE EARLY WARNING SYSTEMS NETWORK (FEWS NET) August 2011 Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Methodology ................................................................................................................................................. 4 National Livelihoods Zones Map ................................................................................................................... 6 Livelihoods Highlights ................................................................................................................................... 7 National Seasonal Calendar .......................................................................................................................... 9 Rural Livelihood Zones Descriptions ........................................................................................................... 11 Zone 1: Northeast Oases: Dates, Salt and Trade ................................................................................... 11 Zone 2: Aïr Massif Irrigated Gardening ................................................................................................ 14 Zone 3 : Transhumant and Nomad Pastoralism .................................................................................... 17 Zone 4: Agropastoral Belt ..................................................................................................................... -

Macrohabitat and Microhabitat Usage by Two Softshell Turtles (Trionyx Triunguis and Cyclanorbis Senegalensis) in West and Central Africa

Herpetological Conservation and Biology 13(3):642–651. Submitted: 1 December 2017; Accepted: 11 July 2018; Published 16 December 2018. MACROHABITAT AND MICROHABITAT USAGE BY TWO SOFTSHELL TURTLES (TRIONYX TRIUNGUIS AND CYCLANORBIS SENEGALENSIS) IN WEST AND CENTRAL AFRICA GODFREY C. AKANI1, EDEM A. ENIANG2, NIOKING AMADI1, DANIELE DENDI1,3, EMMANUEL M. HEMA4, TOMAS DIAGNE5, GABRIEL HOINSOUDÉ SÉGNIAGBETO6, MASSIMILIANO DI VITTORIO7, SULEMANA BAWA GBEWAA8, OLIVIER S. G. PAUWELS9, LAURENT CHIRIO10, AND LUCA LUISELLI1,3,6,11 1Department of Applied and Environmental Biology, Rivers State University of Science and Technology, Port Harcourt, Nigeria 2Dept. of Forestry and Natural Environmental Management, Faculty of Agriculture, University of Uyo, Private Mail Box 1017, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State, Nigeria 3IDECC - Institute for Development, Ecology, Conservation and Cooperation, via G. Tomasi di Lampedusa 33, I-00144 Rome, Italy 4Université Ouaga 1 Professeur Joseph Ki ZERBO/CUP-D, laboratoire de Biologie et Ecologie Animales, 09 BP 848, Ouagadougou 09, Burkina Faso 5African Chelonian Institute, Post Office Box 449-33022, Ngaparou, Mbour, Senegal 6Department of Zoology, Faculty of Sciences, University of Lomé, Post Office Box. 6057, Lomé, Togo 7Ecologia Applicata Italia, Via Jevolella 2, 90018, Termini Imerese (Palermo), Italy 8Department of Wildlife and Range Management, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Post Office Box 119, Kumasi, Ghana 9Institut Royal des Sciences naturelles de Belgique, Rue Vautier 29, 1000 Brussels, Belgium 1014 rue des roses, 06130 Grasse, France 11Corresponding author, email: [email protected] Abstract.—No field studies have been conducted characterizing the habitat characteristics and eventual spatial resource partitioning between softshell turtles (family Trionychidae) in West and Central Africa.