Emerald City Stone Business Didn’T Come Until 2005

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Ethnographic Study of Sectarian Negotiations Among Diaspora Jains in the USA Venu Vrundavan Mehta Florida International University, [email protected]

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 3-29-2017 An Ethnographic Study of Sectarian Negotiations among Diaspora Jains in the USA Venu Vrundavan Mehta Florida International University, [email protected] DOI: 10.25148/etd.FIDC001765 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Mehta, Venu Vrundavan, "An Ethnographic Study of Sectarian Negotiations among Diaspora Jains in the USA" (2017). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 3204. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/3204 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida AN ETHNOGRAPHIC STUDY OF SECTARIAN NEGOTIATIONS AMONG DIASPORA JAINS IN THE USA A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in RELIGIOUS STUDIES by Venu Vrundavan Mehta 2017 To: Dean John F. Stack Steven J. Green School of International and Public Affairs This thesis, written by Venu Vrundavan Mehta, and entitled An Ethnographic Study of Sectarian Negotiations among Diaspora Jains in the USA, having been approved in respect to style and intellectual content, is referred to you for judgment. We have read this thesis and recommend that it be approved. ______________________________________________ Albert Kafui Wuaku ______________________________________________ Iqbal Akhtar ______________________________________________ Steven M. Vose, Major Professor Date of Defense: March 29, 2017 This thesis of Venu Vrundavan Mehta is approved. -

Transmitting Jainism Through US Pāṭhaśāla

Transmitting Jainism through U.S. Pāṭhaśāla Temple Education, Part 2: Navigating Non-Jain Contexts, Cultivating Jain-Specific Practices and Social Connections, Analyzing Truth Claims, and Future Directions Brianne Donaldson Abstract In this second of two articles, I offer a summary description of results from a 2017 nationwide survey of Jain students and teachers involved in pāṭha-śāla (hereafter “pathshala”) temple education in the United States. In these two essays, I provide a descriptive overview of the considerable data derived from this 178-question survey, noting trends and themes that emerge therein, in order to provide a broad orientation before narrowing my scope in subsequent analyses. In Part 2, I explore the remaining survey responses related to the following research questions: (1) How does pathshala help students/teachers navigate their social roles and identities?; (2) How does pathshala help students/teachers deal with tensions between Jainism and modernity?; (3) What is the content of pathshala?, and (4) How influential is pathshala for U.S. Jains? Key words: Jainism, pathshala, Jain education, pedagogy, Jain diaspora, minority, Jains in the United States, intermarriage, pluralism, future of Jainism, second- and third-generation Jains, Young Jains of America, Jain orthodoxy and neo-orthodoxy, Jainism and science, Jain social engagement Transnational Asia: an online interdisciplinary journal Volume 2, Issue 1 https://transnationalasia.rice.edu https://doi.org/10.25613/3etc-mnox 2 Introduction In this paper, the second of two related articles, I offer a summary description of results from a 2017 nationwide survey of Jain students and teachers involved in pāṭha-śāla (hereafter “pathshala”) temple education in the United States. -

Voliirw(People and Places).Pdf

Contents of Volume II People and Places Preface to Volume II ____________________________ 2 II-1. Perception for Shared Knowledge ___________ 3 II-2. People and Places ________________________ 6 II-3. Live, Let Live, and Thrive _________________ 18 II-4. Millennium of Mahaveer and Buddha ________ 22 II-5. Socio-political Context ___________________ 34 II-6. Clash of World-Views ____________________ 41 II-7. On the Ashes of the Magadh Empire _________ 44 II-8. Tradition of Austere Monks ________________ 50 II-9. Who Was Bhadrabahu I? _________________ 59 II-10. Prakrit: The Languages of People __________ 81 II-11. Itthi: Sensory and Psychological Perception ___ 90 II-12. What Is Behind the Numbers? ____________ 101 II-13. Rational Consistency ___________________ 112 II-14. Looking through the Parts _______________ 117 II-15. Active Interaction _____________________ 120 II-16. Anugam to Agam ______________________ 124 II-17. Preservation of Legacy _________________ 128 II-18. Legacy of Dharsen ____________________ 130 II-19. The Moodbidri Pandulipis _______________ 137 II-20. Content of Moodbidri Pandulipis __________ 144 II-21. Kakka Takes the Challenge ______________ 149 II-22. About Kakka _________________________ 155 II-23. Move for Shatkhandagam _______________ 163 II-24. Basis of the Discord in the Teamwork ______ 173 II-25. Significance of the Dhavla _______________ 184 II-26. Jeev Samas Gatha _____________________ 187 II-27. Uses of the Words from the Past ___________ 194 II-28. Biographical Sketches __________________ 218 II - 1 Preface to Volume II It's a poor memory that only works backwards. - Alice in Wonderland (White Queen). Significance of the past emerges if it gives meaning and context to uncertain world. -

Yale Forum on Religion and Ecology Jainism and Ecology Bibliography

Yale Forum on Religion and Ecology Jainism and Ecology Bibliography Bibliography by: Christopher Key Chapple, Loyola Marymount University, Allegra Wiprud, and the Yale Forum on Religion and Ecology Ahimsa: Nonviolence. Directed by Michael Tobias. Produced by Marion Hunt. Narrated by Lindsay Wagner. Direct Cinema Ltd. 58 min. Public Broadcasting Corporation, 1987. As the first documentary to examine Jainism, this one-hour film portrays various aspects of Jain religion and philosophy, including its history, teachers, rituals, politics, law, art, pilgrimage sites, etc. In doing so, the film studies the relevance of ancient traditions of Jainism for the present day. Ahimsa Quarterly Magazine. 1, no. 1 (1991). Bhargava, D. N. “Pathological Impact of [sic] Environment of Professions Prohibited by Jain Acaryas.” In Medieval Jainism: Culture and Environment, eds. Prem Suman Jain and Raj Mal Lodha, 103–108. New Delhi: Ashish Publishing House, 1990. Bhargava provides a chart and short explanation of the fifteen trades that both sects of Jainism forbid and that contribute to environmental pollution and pathological effects on the human body. Caillat, Colette. The Jain Cosmology. Translated by R. Norman. Basel: Ravi Kumar. Bombay: Jaico Publishing House, 1981. Chapple, Christopher Key. “Jainism and Ecology.” In When Worlds Converge: What Science and Religion Tell Us about the Story of the Universe and Our Place In It, eds. Clifford N. Matthews, Mary Evelyn Tucker, and Philip Hefner, 283-292. Chicago: Open Court, 2002. In this book chapter, Chapple provides a basic overview of the relationship of Jainism and ecology, discussing such topics as biodiversity, environmental resonances and social activism, tensions between Jainism and ecology, and the universe filled with living beings. -

Courses in Jaina Studies

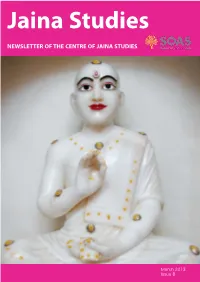

Jaina Studies NEWSLETTER OF THE CENTRE OF JAINA STUDIES March 2013 Issue 8 CoJS Newsletter • March 2013 • Issue 8 Jaina Studies NEWSLETTER OF THE CENTRE OF JAINA STUDIES Contents: 4 Letter from the Chair Conferences and News 5 Jaina Logic: Programme 7 Jaina Logic: Abstracts 10 Biodiversity Conservation and Animal Rights: SOAS Jaina Studies Workshop 2012 12 SOAS Workshop 2014: Jaina Hagiography and Biography 13 Jaina Studies at the AAR 2012 16 The Intersections of Religion, Society, Polity, and Economy in Rajasthan 18 DANAM 2012 19 Debate, Argumentation and Theory of Knowledge in Classical India: The Import of Jainism 21 The Buddhist and Jaina Studies Conference in Lumbini, Nepal Research 24 A Rare Jaina-Image of Balarāma at Mt. Māṅgī-Tuṅgī 29 The Ackland Art Museum’s Image of Śāntinātha 31 Jaina Theories of Inference in the Light of Modern Logics 32 Religious Individualisation in Historical Perspective: Sociology of Jaina Biography 33 Daulatrām Plays Holī: Digambar Bhakti Songs of Springtime 36 Prekṣā Meditation: History and Methods Jaina Art 38 A Unique Seven-Faced Tīrthaṅkara Sculpture at the Victoria and Albert Museum 40 Aspects of Kalpasūtra Paintings 42 A Digambar Icon of the Goddess Jvālāmālinī 44 Introducing Jain Art to Australian Audiences 47 Saṃgrahaṇī-Sūtra Illustrations 50 Victoria & Albert Museum Jaina Art Fund Publications 51 Johannes Klatt’s Jaina-Onomasticon: The Leverhulme Trust 52 The Pianarosa Jaina Library 54 Jaina Studies Series 56 International Journal of Jaina Studies 57 International Journal of Jaina Studies (Online) 57 Digital Resources in Jaina Studies at SOAS Jaina Studies at the University of London 58 Postgraduate Courses in Jainism at SOAS 58 PhD/MPhil in Jainism at SOAS 59 Jaina Studies at the University of London On the Cover Gautama Svāmī, Śvetāmbara Jaina Mandir, Amṛtsar 2009 Photo: Ingrid Schoon 2 CoJS Newsletter • March 2013 • Issue 8 Centre of Jaina Studies Members SOAS MEMBERS Honorary President Professor Christopher Key Chapple Dr Hawon Ku Professor J. -

Newsletter of the Centre of Jaina Studies

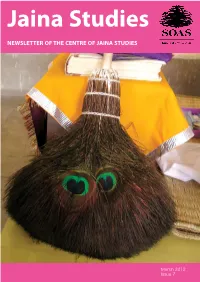

Jaina Studies NEWSLETTER OF THE CENTRE OF JAINA STUDIES March 2012 Issue 7 CoJS Newsletter • March 2012 • Issue 7 Jaina Studies NEWSLETTER OF THE CENTRE OF JAINA STUDIES Contents: 4 Letter from the Chair Conferences and News 5 Biodiversity Conservation and Animal Rights: Religious and Philosophical Perspectives: Programme 7 Biodiversity Conservation and Animal Rights: Religious and Philosophical Perspectives: Abstracts 11 The Paul Thieme Lectureship in Prakrit 12 Jaina Narratives: SOAS Jaina Studies Workshop 2011 15 SOAS Workshop 2013: Jaina Logic 16 Old Voices, New Visions: Jains in the History of Early Modern India at the AAS 18 How Do You ‘Teach’ Jainism? 20 Sanmarga: International Conference on the Influence of Jainism in Art, Culture & Literature 22 Jaina Studies Section at the 15th World Sanskrit Conference 24 Jiv Daya Foundation: Jainism Heritage Preservation Effort 24 Jaina Studies Certificate at SOAS Research 25 Stūpa as Tīrtha: Jaina Monastic Funerary Monuments 28 Peacock-Feather Broom (Mayūra-Picchī): Jaina Tool for Non-Violence 30 A Digambar Icon of 24 Jinas at the Ackland Art Museum 34 Life and Works of the Kharatara Gaccha Monk Jinaprabhasūri (1261-1333) 37 Jains in the Multicultural Mughal Empire 40 Fragile Virtue: Interpreting Women’s Monastic Practice in Early Medieval India Jaina Art 42 The Elegant Image: Bronzes at the New Orleans Museum of Art 45 Notes on Nudity in Digambara Jaina Art 47 Victoria & Albert Museum Jaina Art Fund 48 Continuing the Tradition: Jaina Art History in Berlin Publications 49 Jaina Studies Series 51 International Journal of Jaina Studies 52 International Journal of Jaina Studies (Online) 52 Digital Resources in Jaina Studies at SOAS Prakrit Studies 53 Prakrit Courses at SOAS Jaina Studies at the University of London 54 Postgraduate Courses in Jainism at SOAS 54 PhD/MPhil in Jainism at SOAS 55 Jaina Studies at the University of London On the Cover The Peacock-Feather Broom (mayūra-picchī) of Āryikā Muktimatī Mātājī, in the Candraprabhu Digambara Jain Baṛā Mandira, in Bārābaṅkī/U.P. -

46519598.Pdf

AUCTIONING THE DREAMS: ECONOMY, COMMUNITY AND PHILANTHROPY IN A NORTH INDIAN CITY ROGER GRAHAM SMEDLEY A thesis submitted for a Ph.D. Degree, London School of Economics, University of London 199 3 UMI Number: U615785 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615785 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Th e s e s F 722s The debate on Indian entrepreneurship largely revolves around Weber’s Protestant ethic thesis, its applicability to non-western countries and his comparative study of the sub continent’s religions. However, India historically possessed a long indigenous entrepreneurial tradition which was represented by a number of business communities. The major hypothesis of this dissertation is that the socio-cultural milieu and practices of certain traditional business communities generates entrepreneurial behaviour, and this behaviour is compatible with contemporary occidental capitalism. This involves an analysis of the role of entrepreneurship and business communities in the Indian economy; specifically, a Jain community in the lapidary industry of Jaipur: The nature of business networks - bargaining, partnerships, credit, trust and the collection of information - and the identity of the family with the business enterprise, concluding with a critique of dichotomous models of the economy. -

Jain Declaration on the Climate Crisis

Jain Declaration on the Climate Crisis In 1990, Indian former High Commissioner to the UK and member of parliament, L. M. Singhvi, wrote the “Jain Declaration on Nature” which outlined the fundamental teachings of the Jain religion and its 1 inextricable connection to the preservation of nature. 0F As stated there, “waste and creating pollution are acts of violence”. Almost 30 years later, there is an urgent need for action on the climate crisis. We set forth this declaration to add our voices to those of other faith communities and sectors of the global community. Jainism is one of the world’s oldest religions, having originated in Northern India well before 500 BCE and, as underscored by “The Jain Declaration on Nature”, it is an ecological religion whose philosophies and codes of conduct inherently provide solutions to address our current crisis of global heating and extreme weather events. The principal tenet of conduct followed by Jains is that of Ahimsa or non-violence to any living being. As a result, practicing Jains are vegetarians and have a long history of building sanctuaries for injured animals. Jains teachings prohibit Jains from engaging in professions that harm plants, animals and the earth. Another key tenet followed by Jains is Aparigraha (non-possessiveness), to limit one’s consumption and material possessions. Ahimsa and Aparigraha as taught and traditionally practiced have great relevance to the climate crisis. Other aspects of Jain philosophy are exemplified by the traditional teaching: Parasparo Pagraho 2 Jivanam 1F meaning all life is bound together by mutual support and interdependence, or as an alternate translation, souls render service to each other. -

Jainism in Medieval India (1300-1800) Prologue

JAINISM IN MEDIEVAL INDIA (1300-1800) PROLOGUE - English Translation by S.M. Pahedia It is essential to weigh the contemporary social and political background while considering the conditions and thriving of Jainism in mediaeval India. During this period, Indian society was traditionally divided into Hindu and Jain religion. Buddhism had well-nigh disappeared from Indian scenario. The Indian socio-cultural infrastructure faced sufficient change owing to the influence of Islam that infiltrated into India through the medium of the Arab, the Turk, the Mughal and the Afghan attacks. Though the new entrants too were by and large divided into Sunni, Shiya and Sufi sects, they were all bound firmly to Islam. Ofcourse, Islam brought in new life-values and life-styles in Indian life owing to which the inevitability for reconsidering the shape of social structure and traditional-philosophico facets was felt, perhaps very badly. And this very condition caused rise of some new sects like Bhakti, Saint and Sikh invigorated primarily by the Vedantist, Ramanuja, Madhav, Nimbark, Ramanand Chaitanya, Vallabha etc. With this cultural background, centuries old Digambara and Shavetambara amnay (tradition) was telling its own separate tale. Fore more than one reason, these branches were further divided into sects, sub-sects, ganas , gachchas , anvayas , sanghas & C. as time rolled by. Same way, Bhattaraka, Chaityavasi, Taranpanth, Sthanakvasi practices came into view introducing their own religious formalities, life-fashions, code of conduct, and to some extent the philosophical views. Such being the condition, Jainism of medioeval India witnessed its wide extension. At the same time, it met with certain difficulty also. -

1-14 the Invention of Jainism a Short History of Jaina St

International Journal of Jaina Studies (Online) Vol. 1, No. 1 (2005) 1-14 THE INVENTION OF JAINISM A SHORT HISTORY OF JAINA STUDIES Peter FlŸgel It is often said that Jains are very enthusiastic about erecting temples, shrines or upāśrayas but not much interested in promoting religious education, especially not the modern academic study of Jainism. Most practising Jains are more concerned with the ’correct’ performance of rituals rather than with the understanding of their meaning and of the history and doctrines of the Jain tradition. Self-descriptions such as these undoubtedly reflect important facets of contemporary Jain life, though the attitudes toward higher education have somewhat changed during the last century. This trend is bound to continue due to the demands of the information based economies of the future, and because of the vast improvements in the formal educational standards of the Jains in India. In 1891, the Census of India recorded a literacy rate of only 1.4% amongst Jain women and of 53.4% amongst Jain men.1 In 2001, the female literacy rate has risen to 90.6% and for the Jains altogether to 94.1%. Statistically, the Jains are now the best educated community in India, apart from the Parsis.2 Amongst young Jains of the global Jain diaspora University degrees are already the rule and perceived to be a key ingredient of the life-course of a successful Jain. However, the combined impact of the increasing educational sophistication and of the growing materialism amongst the Jains on traditional Jain culture is widely felt and often lamented. -

This Is a Special Issue on Jain Shashan Prabhavak Vrgandhi's

Ahimsa Foundation September, 2014 Vol. No. 169 in Community Service for 14 Continuous World Over + 100000 The Only Jain E-Magazine Years Readership This is a Special Issue on Jain Shashan Prabhavak V.R.Gandhi’s 150th Birth Anniversary Courtesy : Pankaz Chandmal Hingarh TEMPLES NATIONWIDE CAMPAIGN TO SAVE JAIN HERITAGE TEMPLE The Jain Mutt at Moodabidri, has launched a campaign to declare the culture rich temple Tribhuvana Tilaka Chudamani, popularly known as the thousand-pillar basadi, as a heritage site. The community has also launched an online campaign on Avaaz.org to urge the Prime Minister of India to give the temple the heritage tag. The temple, built in 1430 AD, is now a sorry sight, with its crumbling walls and damaged roof. The temple complex, that houses a sub- shrine called Bhairadevi Mantap, has developed cracks. A part of the cornice fell about three years ago." The three-storey temple complex, which is about 60 feet in height, is managed by the Jain Mutt of Moodabidri. The degeneration has been rapid during the last three years. The single stone "mana stambha" in front of "Bhairadevi Mantapa" is 50-foot tall. It has been erected on an eight-foot pedestal. The mantapa had about 200 stone carvings depicting animals, yoga, sports, birds, war scenes, soldiers, characters of puranas and so on. The mutt has been restoring this temple from time to time, but the massive stone structures have now started developing cracks and the delicate stone cornices have started crumbling. The temple is an important tourist destination. On an average about 500 tourists visit the temple every day. -

Roots, Routes, and Routers: Social and Digital Dynamics in the Jain Diaspora

religions Article Roots, Routes, and Routers: Social and Digital Dynamics in the Jain Diaspora Tine Vekemans Department of Languages and Cultures, Ghent University, 9000 Ghent, Belgium; [email protected] Received: 15 March 2019; Accepted: 1 April 2019; Published: 6 April 2019 Abstract: In the past three decades, Jains living in diaspora have been instrumental in the digital boom of Jainism-related websites, social media accounts, and mobile applications. Arguably, the increased availability and pervasive use of different kinds of digital media impacts how individuals deal with their roots; for example, it allows for greater contact with family and friends, but also with religious figures, back in India. It also impacts upon routes—for example, it provides new ways for individual Jains to find each other, organize, coordinate, and put down roots in their current country of residence. Using extensive corpora of Jainism-related websites and mobile applications (2013–2018), as well as ethnographic data derived from participant observation, interviews, and focus groups conducted in the United States, United Kingdom, and Belgian Jain communities (2014–2017), this article examines patterns of use of digital media for social and religious purposes by Jain individuals and investigates media strategies adopted by Jain diasporic organizations. It attempts to explain commonalities and differences in digital engagement across different geographic locations by looking at differences in migration history and the layout of the local Jain communities.