The Impeachment of John Pickering Author(S): Lynn W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IMPEACHMENT AS a POLITICAL WEAPON THESIS Presented to The

371l MoA1Y IMPEACHMENT AS A POLITICAL WEAPON THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Sally Jean Bumpas Collins, B. A. Denton, Texas December, 1977 Collins, Sally J, B., Impeachment as a Political Weapon. Master of Arts (History), December, 1977, 135 pp., appendices, bibliography, 168 titles, This study is concerned with the problem of determining the nature of impeachable offenses through an analysis of the English theory of impeachment, colonial impeachment practice, debates in the constitutional convention and the state rati- fying conventions, The Federalist Papers and debates in the first Congress, In addition, the precedents established in American cases of impeachment particularly in the trials of Judge John Pickering, Justice Samuel Chase and President Andrew Johnson are examined. Materials for the study included secondary sources, con- gressional records, memoirs, contemporary accounts, government documents, newspapers and trial records, The thesis concludes that impeachable of fenses include non-indictable behavior and exclude misconduct outside official duties and recommends some alternative method of removal for federal judges. TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND OF IMPEACHMENT ,, . ! e ! I 9I1I 1 ITI THE IMPEACHMENT ISSUE IN EARLY AMERICAN HISTORY I I I I I I I I 12 III. THE PICKERING TRIAL . 32 IV. THE CHASE TRIAL ... ... 0 . .0. .. 51 V. EPILOGUE AND CONCLUSION 77 .... 0 0 -APPENDICES0.--- -

![Lco~[), Nrev~ Lham~Sfn~[E ]977 SUPREME COURT of NEW HAMPSHIRE Appoi Nted](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9794/lco-nrev-lham-sfn-e-977-supreme-court-of-new-hampshire-appoi-nted-1049794.webp)

Lco~[), Nrev~ Lham~Sfn~[E ]977 SUPREME COURT of NEW HAMPSHIRE Appoi Nted

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. 6~N ~~~~'L~©DUCu~©u~ U(Q ll~HE ~£~"~rr»~~h\~lE (ot1l~u g~ U\]~V~ li"~A[~rr~s.~~Du 8 1.\ COU\!lCO~[), NrEV~ lHAM~Sfn~[E ]977 SUPREME COURT OF NEW HAMPSHIRE Appoi nted_ Frank R. Kenison, Chief Justice Apri 1 29, 1952 Edward J. Lampron, Senior Justice October 5, 1949 William A. Grimes, Associate Justice December 12, 1966 Maurice P. Bois, Associate Justice October 5, 1976 Charles G. Douglas, III, Associate Justice January 1, 1977 George S. Pappagianis Clerk of Supreme Court Reporter of Decisions li:IDdSlWi&iImlm"'_IIIII'I..a_IIIHI_sm:r.!!!IIIl!!!!__ g~_~= _________ t.':"':iIr_. ____________ .~ • • FE~l 2 ~: 1978 J\UBttst,1977 £AU • "1 be1.J..e.ve. tha..:t oWl. c.oWtt hM pWl-Oue.d a. -6te.a.dy c.OWl-Oe. tfvtoughoL1;t the. ye.aJlA, tha..:t U ha.6 pll.ogll.u-6e.d . a.nd a.ppUe.d the. pJUnuplu 06 OUll. law-6 -Ln a. ma.nne.ll. c.o Y!.-6-L-6te.r"t wUh the. pubUc. iMe.Il.Ut a.nd that aU the. jud-LuaJty w-L.U c..oJ1-ti.nue. to be, a. -6a.6e.guaJtd to the. .V,b eJr.;t,[u, 1l.e..6 po MibiJ!ft[u a.nd d-Lg nUy we. c.heJLU h. " Honorable Frank R. Kenison, Chief Justice, Supreme Court of New Hampshire, liThe State of the Judiciary,1I 3 MAR 77 House Record, page 501. -

From Strawbery Banke to Puddle Dock: the Evolution of a Neighborhood, 1630-1850 (Urban Community, Maritime; New Hampshire)

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Doctoral Dissertations Student Scholarship Spring 1984 FROM STRAWBERY BANKE TO PUDDLE DOCK: THE EVOLUTION OF A NEIGHBORHOOD, 1630-1850 (URBAN COMMUNITY, MARITIME; NEW HAMPSHIRE) JOHN WALTER DUREL University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation Recommended Citation DUREL, JOHN WALTER, "FROM STRAWBERY BANKE TO PUDDLE DOCK: THE EVOLUTION OF A NEIGHBORHOOD, 1630-1850 (URBAN COMMUNITY, MARITIME; NEW HAMPSHIRE)" (1984). Doctoral Dissertations. 1423. https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation/1423 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this document, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark, it is an indication of either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, duplicate copy, or -copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed. -

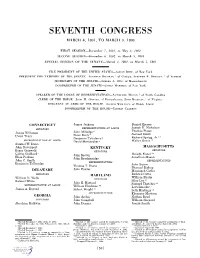

H. Doc. 108-222

SEVENTH CONGRESS MARCH 4, 1801, TO MARCH 3, 1803 FIRST SESSION—December 7, 1801, to May 3, 1802 SECOND SESSION—December 6, 1802, to March 3, 1803 SPECIAL SESSION OF THE SENATE—March 4, 1801, to March 5, 1801 VICE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES—AARON BURR, of New York PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE OF THE SENATE—ABRAHAM BALDWIN, 1 of Georgia; STEPHEN R. BRADLEY, 2 of Vermont SECRETARY OF THE SENATE—SAMUEL A. OTIS, of Massachusetts DOORKEEPER OF THE SENATE—JAMES MATHERS, of New York SPEAKER OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES—NATHANIEL MACON, 3 of North Carolina CLERK OF THE HOUSE—JOHN H. OSWALD, of Pennsylvania; JOHN BECKLEY, 4 of Virginia SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE HOUSE—JOSEPH WHEATON, of Rhode Island DOORKEEPER OF THE HOUSE—THOMAS CLAXTON CONNECTICUT James Jackson Daniel Hiester Joseph H. Nicholson SENATORS REPRESENTATIVES AT LARGE Thomas Plater James Hillhouse John Milledge 6 Peter Early 7 Samuel Smith Uriah Tracy 12 Benjamin Taliaferro 8 Richard Sprigg, Jr. REPRESENTATIVES AT LARGE 13 David Meriwether 9 Walter Bowie Samuel W. Dana John Davenport KENTUCKY MASSACHUSETTS SENATORS Roger Griswold SENATORS 5 14 Calvin Goddard John Brown Dwight Foster Elias Perkins John Breckinridge Jonathan Mason John C. Smith REPRESENTATIVES REPRESENTATIVES Benjamin Tallmadge John Bacon Thomas T. Davis Phanuel Bishop John Fowler DELAWARE Manasseh Cutler SENATORS MARYLAND Richard Cutts William Eustis William H. Wells SENATORS Samuel White Silas Lee 15 John E. Howard Samuel Thatcher 16 REPRESENTATIVE AT LARGE William Hindman 10 Levi Lincoln 17 James A. Bayard Robert Wright 11 Seth Hastings 18 REPRESENTATIVES Ebenezer Mattoon GEORGIA John Archer Nathan Read SENATORS John Campbell William Shepard Abraham Baldwin John Dennis Josiah Smith 1 Elected December 7, 1801; April 17, 1802. -

President Thomas Jefferson V. Chief Justice John Marshall by Amanda

A Thesis Entitled Struggle to Define the Power of the Court: President Thomas Jefferson v. Chief Justice John Marshall By Amanda Dennison Submitted as partial fulfillment of the requirements for The Master of Arts in History ________________________ Advisor: Diane Britton ________________________ Graduate School The University of Toledo August 2005 Copyright © 2005 This document is copyrighted material. Under copyright law, no parts of this document may be reproduced without the expressed permission of the author. Acknowledgments Finishing this step of my academic career would not have been possible without the support from my mentors, family, and friends. My professors at the University of Toledo have supported me over the past three years and I thank them for their inspiration. I especially thank Professors Alfred Cave, Diane Britton, Ronald Lora, and Charles Glaab for reading my work, making corrections, and serving as advisors on my thesis committee. I am eternally grateful to the University of Toledo History Department for their financial and moral support. When I came to the University of Toledo, I would not have survived my first graduate seminar, let alone long enough to finish this project without the experience from my undergraduate career at Southwestern Oklahoma State University. I thank Professors Laura Endicott and John Hayden for their constant support, reading drafts, and offering suggestions and Professors Roger Bromert and David Hertzel for encouraging me via email and on my visits back to Southwestern. Ya’ll are the best. I have a wonderful support system from my family and friends, especially my parents and brother. Thank you Mom and Dad for your encouragement and love. -

Washington City, 1800-1830 Cynthia Diane Earman Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School Fall 11-12-1992 Boardinghouses, Parties and the Creation of a Political Society: Washington City, 1800-1830 Cynthia Diane Earman Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Earman, Cynthia Diane, "Boardinghouses, Parties and the Creation of a Political Society: Washington City, 1800-1830" (1992). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 8222. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/8222 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BOARDINGHOUSES, PARTIES AND THE CREATION OF A POLITICAL SOCIETY: WASHINGTON CITY, 1800-1830 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The Department of History by Cynthia Diane Earman A.B., Goucher College, 1989 December 1992 MANUSCRIPT THESES Unpublished theses submitted for the Master's and Doctor's Degrees and deposited in the Louisiana State University Libraries are available for inspection. Use of any thesis is limited by the rights of the author. Bibliographical references may be noted, but passages may not be copied unless the author has given permission. Credit must be given in subsequent written or published work. A library which borrows this thesis for use by its clientele is expected to make sure that the borrower is aware of the above restrictions. -

Revolutionary New Hampshire and the Loyalist Experience: "Surely We Have Deserved a Better Fate"

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Doctoral Dissertations Student Scholarship Spring 1983 REVOLUTIONARY NEW HAMPSHIRE AND THE LOYALIST EXPERIENCE: "SURELY WE HAVE DESERVED A BETTER FATE" ROBERT MUNRO BROWN Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation Recommended Citation BROWN, ROBERT MUNRO, "REVOLUTIONARY NEW HAMPSHIRE AND THE LOYALIST EXPERIENCE: "SURELY WE HAVE DESERVED A BETTER FATE"" (1983). Doctoral Dissertations. 1351. https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation/1351 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this document, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark, it is an indication of either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, duplicate copy, or copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed. -

Cherish?” Or New Hampshire's Founding Fathers Put the State in Charge of School Funding and Taxation

What Did They Mean By “Cherish?” or New Hampshire's Founding Fathers Put the State in Charge of School Funding and Taxation Doug Hall, NH School Funding Fairness Project December 30, 2019 Introduction Knowledge and learning, generally diffused through a community, being essential to the preservation of a free government; and spreading the opportunities and advantages of education through the various parts of the country, being highly conducive to promote this end; it shall be the duty of the legislators and magistrates, in all future periods of this government, to cherish the interest of literature and the sciences, and all seminaries and public schools,… Part 2, Article 83 of the New Hampshire Constitution What did the writers mean by “cherish” in 1784? This question has been debated and old dictionaries have been consulted. For example, in the 1792 edition of the Dictionary of the English Language by Samuel Johnson one finds this definition: “to support; to shelter; to nurse up.” A better way to understand what they meant is to determine what they actually did in regard to public schools at the time the Constitution was adopted and shortly thereafter. The Transition from Provincial Government to Statehood In the early 1770s, the province of New Hampshire operated under the laws of Great Britain and the supreme authority of King George as represented by the Royal Governor, John Wentworth. As the War for Independence waged in 1775, Governor Wentworth departed from Portsmouth, leaving the province without an effective government. In December 1775, a provincial congress in New Hampshire drafted a constitution that took effect on January 5, 1776. -

MIDNIGHT JUDGES KATHRYN Turnu I

[Vol.109 THE MIDNIGHT JUDGES KATHRYN TuRNu I "The Federalists have retired into the judiciary as a strong- hold . and from that battery all the works of republicanism are to be beaten down and erased." ' This bitter lament of Thomas Jefferson after he had succeeded to the Presidency referred to the final legacy bequeathed him by the Federalist party. Passed during the closing weeks of the Adams administration, the Judiciary Act of 1801 2 pro- vided the Chief Executive with an opportunity to fill new judicial offices carrying tenure for life before his authority ended on March 4, 1801. Because of the last-minute rush in accomplishing this purpose, those men then appointed have since been known by the familiar generic designation, "the midnight judges." This flight of Federalists into the sanctuary of an expanded federal judiciary was, of course, viewed by the Republicans as the last of many partisan outrages, and was to furnish the focus for Republican retaliation once the Jeffersonian Congress convened in the fall of 1801. That the Judiciary Act of 1801 was repealed and the new judges deprived of their new offices in the first of the party battles of the Jeffersonian period is well known. However, the circumstances surrounding the appointment of "the midnight judges" have never been recounted, and even the names of those appointed have vanished from studies of the period. It is the purpose of this Article to provide some further information about the final event of the Federalist decade. A cardinal feature of the Judiciary Act of 1801 was a reform long advocated-the reorganization of the circuit courts.' Under the Judiciary Act of 1789, the judicial districts of the United States had been grouped into three circuits-Eastern, Middle, and Southern-in which circuit court was held by two justices of the Supreme Court (after 1793, by one justice) ' and the district judge of the district in which the court was sitting.5 The Act of 1801 grouped the districts t Assistant Professor of History, Wellesley College. -

Dilemma of the American Lawyer in the Post-Revolutionary Era, 35 Notre Dame L

Notre Dame Law Review Volume 35 | Issue 1 Article 2 12-1-1959 Dilemma of the American Lawyer in the Post- Revolutionary Era Anton-Hermann Chroust Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/ndlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Anton-Hermann Chroust, Dilemma of the American Lawyer in the Post-Revolutionary Era, 35 Notre Dame L. Rev. 48 (1959). Available at: http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/ndlr/vol35/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by NDLScholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Notre Dame Law Review by an authorized administrator of NDLScholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE DILEMMA OF THE AMERICAN LAWYER IN THE POST-REVOLUTIONARY ERA Anton-Hermann Chroust* On the eve of the Revolution the legal profession in the American colonies,' in the main, had achieved both distinction and recognition. It had come to enjoy the respect as well as the confidence of the people at large. This is borne out, for instance, by the fact that twenty-five of the fifty-six signers of the Declaration of Independence, and thirty-one of the fifty-five members of the Constitutional Convention were lawyers. Of the thirty-one lawyers who attended the Constitutional Convention, no less than five had studied law in England.2 The American Revolution itself, directly and indirectly, affected the legal profession in a variety of ways. First, the profession itself lost a considerable number of its most prominent members; secondly, a bitter antipathy against the lawyer as a class soon made itself felt throughout the country; thirdly, a strong dislike of everything English, including the English common law became wide- spread; and fourthly, the lack of a distinct body of American law as well as the absence of American law reports and law books for a while made the administra- tion of justice extremely difficult and haphazard. -

History of the New Hampshire Federal Courts

HISTORY OF THE NEW HAMPSHIRE FEDERAL COURTS Prepared by the Clerk’s Office of the United States District Court for the District of New Hampshire - 1991 1 HISTORY OF THE NEW HAMPSHIRE FEDERAL COURTS TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE & ACKNOWLEDGMENT .......................................................................................... 5 INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 7 THE UNITED STATES CIRCUIT COURT ................................................................................ 11 Time Line for the Circuit Court and Related Courts ................................................................ 19 JUDGES OF THE CIRCUIT COURT ......................................................................................... 20 John Lowell ............................................................................................................................... 20 Benjamin Bourne ...................................................................................................................... 21 Jeremiah Smith.......................................................................................................................... 21 George Foster Shepley .............................................................................................................. 22 John Lowell ............................................................................................................................... 23 Francis Cabot Lowell ............................................................................................................... -

524 Page 400 Cont (259) State of New Hampshire, Rockingham

524 Page 400 cont (259) State of New Hampshire, Rockingham: Chichester March 11, 1795 At a legal Annual meeting of the Inhabitants of the Town of Chichester met according to notification Date of warrant July 20, 1795 1. Deacon Abraham chosen moderator of said meeting Page 401 2. The votes were brought in for a Governor as follows: John Gilman – 63 3. The Votes were brought in for a Councillor for the County of Rockingham as follows James Sheaf – 56 4. The votes were brought in for a Senator for the fourth District as follows: Michael McClary– 61 5. The votes were brought in for a recorder of Deeds for the County of Rockingham as fol- lows: James Gray – 57 6. The votes were brought in for a County Treasurer as follows: Oliver Peabody– 48 7. Voted to Except the Selectmens accounts 8. Capt Edmund Leavitt, Joshua Lane, Mr Moses Seavey Chosen Selectmen for the Ensuing year 9. The Constables Office Venued and struck off to William Hook who is to pay 10 shillings and 6 pencce for the priviledge of his office and William Edmunds is Accepted by the Town as bondsman for him 10. Voted the Collectors office Vendued and struck of to Joseph Dow who is to Receive 5 pounds 13 shillings for his Service And Lieut John Hilyard is Accepted by the Town for a Dondsman for him Page 402 11. Lt Joshua Lane and Mr Josiah Drake Chosen Tythingmen for the Curant year 12. Lieut John Hilyard,Dea Abraham True, Ens Benjamin Jackson Chosen for a Committee of Audit 13.