Valuation of William Demant Holding A/S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Morningstar® Developed Markets Ex-North America Target Momentum Indexsm 18 June 2021

Morningstar Indexes | Reconstitution Report Page 1 of 8 Morningstar® Developed Markets ex-North America Target Momentum IndexSM 18 June 2021 The index consists of liquid equities that display above-average return on equity. The indexes also emphasize stocks with increasing fiscal For More Information: earnings estimates and technical price momentum indicators. http://indexes.morningstar.com US: +1 312 384-3735 Europe: +44 20 3194 1082 Reconstituted Holdings Name Ticker Country Sector Rank (WAFFR) Weight (%) KUEHNE & NAGEL INTL AG-REG KNIN Switzerland Industrials 1 0.50 PostNL NV PNL Netherlands Industrials 2 0.50 Uponor Corporation UPONOR Finland Industrials 3 0.51 Smart Metering Systems PLC SMS United Kingdom Industrials 4 0.50 QT GROUP OYJ QTCOM Finland Technology 5 0.50 ASML Holding NV ASML Netherlands Technology 6 0.51 Vectura Group PLC VEC United Kingdom Healthcare 7 0.50 Lasertec Corp 6920 Japan Technology 8 0.52 Troax Group AB Class A TROAX Sweden Industrials 9 0.48 BayCurrent Consulting Inc 6532 Japan Technology 10 0.50 Sagax AB B Shares SAGA B Sweden Real Estate 11 0.50 Bilia AB A BILIa Sweden Consumer Cyclical 12 0.51 Mycronic AB MYCR Sweden Technology 13 0.49 Protector Forsikring ASA PROTCT Norway Financial Services 14 0.49 AP Moller - Maersk AS B MAERSK B Denmark Industrials 15 0.50 Polar Capital Holdings PLC POLR United Kingdom Financial Services 16 0.51 Secunet Security Networks AG YSN Germany Technology 17 0.50 Hermes Intl RMS France Consumer Cyclical 18 0.50 Kety KTY Poland Basic Materials 19 0.51 ASM Intl ASMI Netherlands Technology 20 0.51 Nippon Yusen KK 9101 Japan Industrials 21 0.54 Dexerials Corp. -

Proxy Vote Record

Company Name Ticker Country Meeting Date Proposal Text Vote Instruction A.P. Moller-Maersk A/S MAERSK.B Denmark 23-Mar-20 Receive Report of Board A.P. Moller-Maersk A/S MAERSK.B Denmark 23-Mar-20 Accept Financial Statements and Statutory Reports For A.P. Moller-Maersk A/S MAERSK.B Denmark 23-Mar-20 Approve Discharge of Management and Board For A.P. Moller-Maersk A/S MAERSK.B Denmark 23-Mar-20 Approve Allocation of Income and Dividends of DKK 150 Per Share For A.P. Moller-Maersk A/S MAERSK.B Denmark 23-Mar-20 Reelect Jim Hagemann Snabe as Director For A.P. Moller-Maersk A/S MAERSK.B Denmark 23-Mar-20 Reelect Ane Maersk Mc-Kinney Uggla as Director For A.P. Moller-Maersk A/S MAERSK.B Denmark 23-Mar-20 Reelect Robert Maersk Uggla as Director For A.P. Moller-Maersk A/S MAERSK.B Denmark 23-Mar-20 Reelect Jacob Andersen Sterling as Director For A.P. Moller-Maersk A/S MAERSK.B Denmark 23-Mar-20 Reelect Thomas Lindegaard Madsen as Director For A.P. Moller-Maersk A/S MAERSK.B Denmark 23-Mar-20 Ratify PricewaterhouseCoopers as Auditors For A.P. Moller-Maersk A/S MAERSK.B Denmark 23-Mar-20 Authorize Board to Declare Extraordinary Dividend For A.P. Moller-Maersk A/S MAERSK.B Denmark 23-Mar-20 Approve DKK 784.9 Million Reduction in Share Capital via Share Cancellation For A.P. Moller-Maersk A/S MAERSK.B Denmark 23-Mar-20 Approve Guidelines for Incentive-Based Compensation for Executive Management and Board Against A.P. -

Remuneration in Danish Large Cap Companies Benchmarking of Remuneration of Executive Management and Boards 2013 - 2016 Remuneration in Danish Large Cap Companies

Remuneration in Danish Large Cap companies Benchmarking of remuneration of executive management and boards 2013 - 2016 Remuneration in Danish Large Cap companies Content Introduction 3 Key takeaways 4 Current trends 5 Experience from the UK 8 Overview 9 Methodology 10 Remuneration of executive directors 11 Base salary 15 Pension 18 Bonus (STIs) 19 Long-Term Incentives (LTIs) 22 Board remuneration 31 How can Deloitte help? 32 Our contacts 33 Appendix 35 2 Remuneration in Danish Large Cap companies Introduction This report gives an overview of and insight into reported with the required level of detail to be included remuneration of executive directors and boards of listed in our analysis. All the included company reports companies within the Danish Large Cap1 index. In March in accordance with IFRS and financial reporting on 2017 the Large Cap Index is comprised of 38 companies, remuneration of executives are more specifically of which the names can be found in a list in the appendix. governed by IFRS 2 and the Danish Financial Statements These companies represent some of the largest Danish Act. Remuneration of executive directors is required by companies from a wide range of industries, from financial IFRS to be disclosed on both fixed and variable elements services to energy and supplies. for executive management. Although reporting this level of detail for all individual members of management is During 2016 no companies left the Danish Large Cap not a requirement, it is however best practice guidance Index, while DFDS, NKT Holding, SimCorp and Össur from the Committee on Corporate Governance3. LTI entered following OMX Nasdaq’s annual review in programmes must also be disclosed separately in their December 2015. -

Danmarks Nationalbank

STATISTI CS DANMARKS NATIONALBANK 26 JULY 2019 PORTFOLIO INVESTMENTS, JUNE 2019 Foreign investors buy Danish shares in the first half of 2019 Foreign investors have bought listed Danish shares sold some Danish shares, including Danske Bank, for kr. 4.3 billion in the first half of 2019. Foreign in- William Demant and ISS. vestors own a total of kr. 1,345 billion Danish shares corresponding to an ownership of 52 per cent of the Novo Nordisk is foreign investor's favorite share Danish stock market. Foreign investors have owned Foreign investors own entire kr. 458 billion of the more than half of Danish shares since the beginning Danish Novo Nordisk B share. The share thus of 2014. amounts to 34 per cent of their total holdings of Dan- ish shares. Next, foreign investors have the largest It is especially shares in the large Danish companies holdings of shares in DSV, Ørsted and Vestas, which such as Novo Nordisk B, A. P. Møller - Mærsk, Ves- they own respectively own kr. 84, 79 and 78 billion of. tas, Genmab and DSV the foreign investors have The four largest shares thus constitute more than half pur-chased. However, foreign investors have also of foreign investors' portfolio of Danish shares. The Novo Nordisk share is also the most popular Dan- ish share with the Danish investors. They own a total Foreign investors have bought for kr. 4.3 billion of kr. 164 billion thereof. However, the share amounts Danish listed shares in 2019 to only 13 per cent of Danish investors' portfolio of Danish shares, which amounts to kr. -

Annual Review 2O12

ANNUAL REVIEW 2O12 AXCEL ANNUAL REVIEW 2O12 WWW.AXCEL.DK AXCELFUTURE – WORKING FOR A BETTER INVESTMENT CLIMATE IN DENMARK 24 AXCEL IN BRIEF AXCEL’S COMPANIES – STRATEGY AND KEY FIGURES 12 28 KEY FIGURES FOR AXCEL’S FUNDS FURTHER – NET PROFIT/LOSS FOR 2012 INFORMATION ABOUT AXCEL 32 40 AXCEL’S AXCEL’S FUNDS INVESTORS 36 34 2 ANNUAL REVIEW 2O12 AXCEL’S BOARDS CREATE VALUE BOARD MANAGEMENT STRUCTURE AT AXCEL-OWNED COMPANIES 18 AXCEL MANAGEMENT AXCEL’S INVESTMENT RESULTS AXCEL’S MANAGEMENT AND INDUSTRIAL BOARDS 6 38 NEWS FOREWORD 10 4 AXCEL SUPPORTS THE GLOBAL COMPACT JOINED GLOBAL 14 COMPACT IN 2O12 WWW.AXCEL.DK 3 GROWING IN A STAGNANT EUROPE The period of low growth in Europe, including Denmark, looks set to persist for a while yet. Denmark’s politicians have done a good job with their Growth Plan, which will, with any luck, kick-start investment, but we remain dependent on developments in the global economy and, especially, our closest trading partners. The work on making Denmark more competitive in terms of preserv- their good work. Bent is one of Axcel’s founding fathers and is retir- ing jobs and attracting capital from abroad is therefore far from over. ing on age grounds after contributing hugely to the foundations for Against this background, we welcome the political signals from par- liament suggesting further reforms across the economy, in areas such as industry (including corporate taxation), education and the labour We must also bid farewell to Hanne after only two years on the board, market. Axcel will be actively involved in this debate through Axcel- because she has been elected to the board of the listed German con- future, as we consider it critical for Denmark’s future. -

Hearing Aids

Equity Research Sector update, 31 March, 2020 18:36 CET Hearing aids COVID-19 crashes market growth: 2020e decline of 9-27% US market and COVID-19 impact in H2 are key swing factors Demant has the most harmful exposure; down to SELL (Hold) GN protected by GN Audio and limited retail exposure; BUY Three scenarios, all negative Many hearing retail stores in Europe are either fully or partly closed. Senior citizens are being asked to stay home. The US (the largest hearing aid market, accounting for one third of its value) is 2-3 weeks behind Europe and is also closing down. A recent survey from US-based Hearing Review confirms a depressing trend. We have modelled three different scenarios looking at the impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on hearing aid market growth. We lean towards the most likely case being that we have a large negative effect in March-May 2020, improvements during the summer, and then a negative second wave (although smaller) in October-December 2020. We estimate this disruption will lead to a market decline of around 18%, and this is our main input for our revised estimates for GN and Demant. Underlying market fundamentals are, however, still robust and we expect market growth of ~8% in 2021 as the market catches up the backlog. Demant downgraded to SELL as retail exposure slices earnings Hearing instruments account for 77% of Demant’s revenue and are currently seeing poor sales for the reasons outlined above. Only EPOS (CC&O franchise and ~8% of total sales) is expected to reach positive growth (~10% in 2020e). -

Annual Report 2017

ANNUAL REPORT 2017 About the front cover Bone anchored hearing systems (BAHS) like Ponto are designed to use your body’s natural ability to transfer sound through bone conduction. The implanted part is discreetly placed through the skin on the scull bone and lets you snap on the sound processor. The powerful sound processor is worn behind the ear and converts sound into vibrations, which are then sent through the skull bone directly to your inner ear. Since its launch, many users and professionals have experienced the difference of Ponto 3 SuperPower, recognising that this product is a game changer. All users of bone anchored hearing systems benefit from a sound processor with the highest pos- sible maximum output. As the most powerful abutment-level sound processor in the market, Ponto 3 SuperPower provides premium sound quality and a unique option for the majority of users of bone anchored hearing systems. “The Ponto has increased my capabilities, my gifts and passions” Camilla Gilbert was born with a hearing loss. She is a BAHS user and has witnessed the benefits of Oticon Medical’s Ponto first-hand. Listen to her story. Read more: demant.com CONTENTS INSIGHTS AND HIGHLIGHTS Key figures and financial ratios 4 CEO letter 8 At a glance 10 Financial review 14 Outlook 20 OUR BUSINESS Hearing Devices 22 Hearing Implants 26 Diagnostic Instruments 28 Personal Communication 30 Strategic Group initiatives 32 SHAREHOLDER INFORMATION AND CORPORATE GOVERNANCE Shareholder information 34 Risk management activities 37 Corporate social responsibility -

Annual Report 2007 a New Era 5

Annual Report 2007 A new era 5 Mission statement 6 2007 at a glance 7 Management’s review Key fi gures and fi nancial ratios 8 Review 10 Shareholder information 22 Risk management activities 24 Corporate governance 26 Board of Directors and Executive Board 29 Financial statements Signatures 30 Accounting policies 32 Income statement 37 Balance sheet at 31 December 38 Cash fl ow statement 40 Statements of changes in equity 41 Notes 44 Subsidiaries and associates 65 Business activities 66 The English text in this document is an unauthorised translation of the Danish original. In the event of any inconsistencies, the Danish version shall apply. 3 4 A new era The current development in the hearing aid market is extremely exciting, market has only recently taken this decisive step into the realm of wireless with new wireless options fundamentally changing the way people with technology: extreme demands for minimising power consumption and the hearing impairment live. size of hearing aids combined with ever-tougher demands for maximising the audiological qualities mean that only a handful of manufacturers can The advent of wireless communication between two hearing aids has operate at the cutting edge of wireless technology. dramatically enhanced sound quality for users with binaural fitting, appreciably improving their ability to localise sources of sound and to For some of the other companies in the William Demant Holding Group, understand speech in noisy surroundings. With wireless technology and however, wireless technology has for many years been a part of their so-called binaural sound processing, it is possible to recreate the user’s day-to-day business: wireless amplifier systems for classrooms, tele- sense of space. -

Is GN Store Nord Priced at a Conglomerate Discount? - a Valuation of GN Audio & GN Hearing

Master’s Thesis Is GN Store Nord Priced at a Conglomerate Discount? - A Valuation of GN Audio & GN Hearing Konglomerat rabat i GN Store Nord – En Værdiansættelse af GN Audio og GN Hearing. Alexander Rosenkrans & Fredrik Myrvold MSC. FINANCE AND ACCOUNTING Supervisor: Palle Nierhof Date of Submission: 15TH May 2017 Number of Pages: 120 Number of Characters Incl. Spaces: 272.266 Number of Standard Pages: 120 EXCECUTIVE SUMMARY: Empiriske undersøgelser har vist at konglomerat selskabers divisioner, hver for sig, repræsenterer en højere værdi end når de værdiansættes som en enhed, derved bliver konglomerat selskaber historisk set værdifastsat lavere, end summen af konglomerat selskabers divisioner hver for sig. Dette betyder at konglomeraters aktiekurs ofte indeholder en rabat, kaldet konglomeratrabat. I denne afhandling er konglomeratrabattens eventuelle eksistens og eventuelle påvirkning på konglomeratet GN Store Nord, undersøgt. Før denne analyse blev gennemført, blev det det teoretiske fundament for konglomeratrabat gransket. De hyppigste forklaringer på konglomeratrabatters eksistens relaterer sig til agent omkostninger og ulemper ved interne kapitalmarkeder. Diskussion omkring agent omkostning tager oftest udgangspunkt i forskellighederne imellem aktionærens og ledelsens risiko profiler. Teorier, der relaterer sig til interne kapitalmarkeder forklarer, at ressource allokeringer mellem divisioner ofte lider under konkurrence fra divisioner med dårlig rentabilitet. Afhandlingen fokuserer primært på at undersøge hvorvidt konglomeratrabat eksisterer i GN Store Nord. Denne analyse tog sit udgangspunkt i en DCF analyse af GN Store Nords to divisioner; GN Audio og GN Hearing. Begge divisioner er værdiansat som individuelle enheder. Divisionernes estimerede markedskurs udgjorde den 09.02.2017, som følge af DCF modellens beregninger DKK 192,35. Sammenholdes dette estimat med markedsværdien på aktiekursen DKK 152,82 per samme dato - var det tydeligt, at vi kom frem til en rabat i aktiekursen. -

Aktieanalyse William Demant

AktieAnalyse William Demant Sælg Manglende opjustering sår tvivl om indtjenings- Uændret Salgsanbefaling siden 18/08/2016 evnen Analysedato: 09/11/2017 Vi fastholder vores Sælg-anbefaling på William Demant. Periodemeddelelsen indikerer, at det gode salgsmomentum fra første halvår 2017 er fortsat ind i an- det halvår. Den fastholdte indtjeningsprognose sår dog efter vores vurdering Aktuel kurs kl. 11:33 tvivl om indtjeningsevnen i en periode med rigtig stærk salgsvækst. 182,00 DKK Stærk salgsvækst i de første ti måneder af 2017 Vi noterer os, at William Demant kan berette, at det positive salgsmomentum fra årets første Begivenhed: seks måneder er fortsat ind i andet halvår 2017. Det er specielt positivt, at William Demant i Periodemeddelelse øjeblikket oplever en stærk salgsudviklingen inden for alle selskabets primære forretnings- områder. Det vidner efter vores vurdering om, at selskabet har en meget konkurrencedygtig produktportefølje. Den attraktive produktportefølje danner, kombineret med et meget effek- tivt distributionsnetværk, fundamentet for den høje salgsvækst i 2017. Seneste analyse: 06/11/17 – Muligt løft af ind- 2017-prognosen bliver fastholdt på trods af meget positive salgsmeldinger tjeningsprognosen i 3. kvar- Vi havde på forhånd ventet, at William Demant ville indsnævre indtjeningsprognosen i den talsmeddelelsen øvre ende i forbindelse med dagens periodemeddelelse. William Demant fastholder dog prognosen for driftsindtjeningen (EBIT) på 2,3-2,6 mia. kr. på trods af de positive salgsmel- dinger fra årets første ti måneder. Vi er overrasket over, at der med kun to måneder tilbage Kalender: af året er så stor usikkerhed omkring indtjeningsniveauet, at William Demant fastholder en indtjeningsprognose med et spænd på 300 mio. -

Annual Report

Annual Report 2020 Evergreen investor We are a long-term investor with keen focus on companies with sustainable business models and structures resembling those of Demant and favourable growth prospects. We believe in ownership longevity as a means of fostering the right conditions for long-term value creation. In short, we are in it for the long haul. 2 Content Letter from the CEO 4 About William Demant Invest 6 At a glance 8 Pro forma consolidation 10 The William Demant Invest companies 12 Demant 14 Össur 16 Vision RT 18 Vitrolife 20 CellaVision 22 Revenio 24 Jeudan 26 Borkum Riffgrund 1 28 Board of Directors 30 Management 32 Environmental, Social and Governance policy 34 Financial report 36 Financial review 38 Key figures and financial ratios 40 Management statement 41 Independent auditor’s report 42 Consolidated financial statements 44 Notes to consolidated financial statements 51 Parent financial statements 106 Notes to parent financial statements 111 Subsidiaries and associates 116 3 Letter from the CEO In 2020, William Demant Invest saw an 8% increase of its market capitalisation to DKK 58 billion, and earn- ings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amorti- sation (EBITDA) of DKK 3,680 million, which was a decrease of 22% compared to 2019. While we can hardly be pleased with the financial performance in 2020, I am very content with the way our companies have handled the devastating coronacrisis and steered through rough seas, leaving them in a solid position and ready to take part in the recovery and upturn we expect to see on the other side of the co- The past year has been a mixed picture for the com- ronacrisis. -

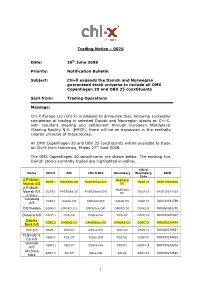

20080626 Trading Notice Functional 0076

Trading Notice – 0076 Date: 26 th June 2008 Priority: Notification Bulletin Subject: Chi-X expands the Danish and Norwegian guaranteed stock universe to include all OMX Copenhagen 20 and OBX 25 constituents Sent from: Trading Operations Message: Chi-X Europe Ltd (Chi-X) is pleased to announce that, following successful completion of trading in selected Danish and Norwegian stocks on Chi-X, with resultant clearing and settlement through European Multilateral Clearing Facility N.V. (EMCF), there will be an expansion in the centrally cleared universe of these stocks. All OMX Copenhagen 20 and OBX 25 constituents will be available to trade on Chi-X from tomorrow, Friday 27 th June 2008. The OMX Copenhagen 20 constituents are shown below. The existing five Danish stocks currently traded are highlighted in yellow. CHI-X Name CHI-X RIC CHI-X RIC Bloomberg Bloomberg ISIN Code A P Moller - MAERSKB MAER.I MAERSKb.CO MAERSKbco.CHI MAER IX DK0010244508 Maersk A/S DC A P Moller - MAERSKA DSAA.I MAERSKa.CO MAERSKaco.CHI DSAA IX DK0010244425 Maersk A/S EC A Share Carlsberg CARP.I CARLb.CO CARLbco.CHI CARLB DC CARP IX DK0010181759 A/S D/S Norden DSNO.I DNORD.CO DNORDco.CHI DNORD DC DSNO IX DK0060083210 Danisco A/S DEMC.I DCO.CO DCOco.CHI DCO DC DEMC IX DK0010207497 Danske DDBC.I DANSKE.CO DANSKEco.CHI DANSKE DC DDBC IX DK0010274414 Bank A/S DSV A/S DSVB.I DSV.CO DSVco.CHI DSV DC DSVB IX DK0060079531 FLSmidth & FLBB.I FLS.CO FLSco.CHI FLS DC FLBB IX DK0010234467 Co A/S Genmab GENM.I GEN.CO GENco.CHI FEN DC GENM IX DK0010272202 A/S GN Store GNTC.I GN.CO