St. Andrew's, Ipplepen a Short Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Coombe House Ipplepen, Devon

Coombe House Ipplepen, Devon Coombe House Ipplepen, Devon A magnificent Grade II listed Georgian country house set in a private and peaceful position surrounded by 70 acres of grounds with a collection of traditional outbuildings. Totnes 4.5 miles, Newton Abbot 5.5 miles (London Paddington 2 hours 30 minutes). Exeter 17 miles (London Paddington 2 hours 3 minutes) (All distances and times are approximate) Ground Floor: Entrance hall | Drawing room | Music room | Study | Dining room | Secondary kitchen | Cloakroom Lower Ground Floor: Kitchen / breakfast room| Scullery | Nursery / Playroom Laundry | Linen room | Wine cellar | Store room | WC First Floor: Principal bedroom with two dressing rooms and en suite bathroom Two further bedrooms both with en suite bathrooms Second Floor: Six bedrooms | Two bathrooms Gardens, grounds and outbuildings Home office| Swimming pool | Garden room and storage| Potting sheds| Kitchen garden Orchard | Formal lawn | Pasture Workshop | Tractor shed| Former piggery | Car port | Collection of traditional barns and stores In all the grounds extend to about 70 acres Exeter Country Department 19 Southernhay East, Exeter 55 Baker Street EX1 1QD London, W1U 8AN Tel: +44 1392 848 842 Tel: +44 20 7861 1717 [email protected] [email protected] knightfrank.co.uk Situation Coombe House sits in a private and peaceful elevated position at the end of a long drive with superb far-reaching views over the surrounding countryside. The property sits on the edge of the village of Coombe Fishacre, equidistant between Newton Abbot and Totnes. Nearby facilities include Ben’s Farm Shop and Riverford Organic near Staverton, Dartington Hall with its International Summer School & Festival and The Barn Cinema showing the latest films and live links to theatre, ballet and opera productions. -

Template for CMB Report

BSS/21/01 Farms Estate Committee 22 February 2021 The County Farms Estate Management and Restructuring Report of the Head of Digital Transformation and Business Support Please note that the following recommendations are subject to consideration and determination by the Committee before taking effect. Recommendation(s): That the Committee approves the recommendations as set out in the opening paragraph of sections 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 of this report. 1.0 Part Higher Henland Farm, Kentisbeare 1.1 It is recommended that Part Higher Henland Farm Kentisbeare, amounting to 9.89 hectares (24.45 acres) or thereabouts of bare land be again let to the tenant of Higher Henland Farm, Kentisbeare on a Farm Business Tenancy agreement commencing 25 March 2022 and terminating 25 March 2024, subject to terms being agreed. 1.2 The Kentisbeare Estate comprises: - Higher Henland Farm – 41.91 hectares (103.58 acres) - Lower Henland Farm – 73.31 hectares (181.07 acres) - Total – 115.22 hectares (284.65 acres) 1.3 Higher Henland Farm is let to the tenant in two separate agreements. The tenancy of the main holding is a 1986 Agricultural Holdings Act ‘retirement’ tenancy. With the legislative amendments made by the Agriculture Act 2020, the earliest date on which the landlord could take back possession of the holding under the Agricultural Holdings Act 1986 Case A provisions is now 25 March 2024. The tenant occupies the remaining 24.45 acres of bare land under a Farm Business Tenancy which commenced on 25 March 2003 and expires 25 March 2022. 1.4 Granting the tenant of Higher Henland Farm a new Farm Business Tenancy of the 24.45 acres of bare land for a further term of 2 years will afford the potential for both agreements to co-terminate. -

Well Here We Go Again and Another Season of Football with What We Now Call the EXETER & DISTRICT YOUTH LEAGUE Sponsored by Red Post Media Solutions

EXETER & DISTRICT YOUTH FOOTBALL LEAGUE 1 EXETER & DISTRICT YOUTH FOOTBALL LEAGUE Well here we go again and another season of Football with what we now call THE EXETER & DISTRICT YOUTH LEAGUE sponsored by Red Post Media Solutions. Towards the end of the 2007/08 season we were approached by what seemed to be an overwhelming majority of our Under-12 clubs who asked if we would provide football for them the following year at under-13 and as a result of the ‘demand’, we agreed. Much has been made of this move and it is only fair to have recorded that we, as a League, and certainly yours truly as Chairman, have never enforced any decision upon the members clubs. Indeed the Management mission is to assist and arrange the provision of what the majority of member clubs wish for. We now offer mini soccer for the age groups under-8, 9 and 10 and then it’s competitive football for the under 11, 12 and 13 age groups. We have, this year, complied with the Football Associations wishes and dispensed with a Cup competition for the under-8s and so our finals day in 2009 will not involve that age group. During the summer we welcomed aboard, as new sponsors Red Post, and they are the driving force behind our fabulous website which keeps everybody up to date with everything that they need to know or indeed find out about. It will not have escaped anybody with half an eye on the media that in the world of professional football there is a serious drive to improve the behaviour of players on the pitch - and I would like to ask ALL our member clubs to ensure that they ‘do their bit’ to help with a campaign of greater RESPECT for both the officials and indeed everybody else connected with the game. -

This Month in Denbury Local Post Office Opening Times February

This Month In Denbury Thursday 2nd Denbury PreSchool Extraordinary General Meeting 7.30pm Church Cottage Denbury Gardening Club, Gardeners' Questions, 7:30pm, Village Hall Coffee Drinkers - Hostess Liz Mills Folk Night, 9pm, Union Inn Saturday 4th February 2017 Issue 193 Scouts’ Paper Collection – Papers out by 9am, please Sunday 5th South Hams Motor Club Primrose Rally Passing by the village approx. 1am Sunday Club meets 9:15am Monday 6th Parish Council Meeting, 7:30pm, Village Hall Tuesday 7th Denbury Stitchers, 7:30pm, Church Cottage Wednesday 8th Pub Quiz, 8pm, Union Inn Thursday 9th Coffee Drinkers - Hostess Valerie Watson-Jackson Coffee Mates, 10:30 – 12 noon, Church Cottage Folk Night, 9pm, Union Inn Saturday 11th Messy Church 3-5pm, Ipplepen Church Hall Sunday 12th No Service in Denbury Monday 13th Half Term begins Tuesday 14th Valentine's Day Thursday 16th Coffee Drinkers - Hostess Mary Avard Mobile Library Folk Night, 9pm, Union Inn Outside School Monday 27th February Friday 17th 2pm – 2.45pm Half Term ends Tuesday 21st Denbury Stitchers, no meeting nd Wednesday 22 Pub Quiz, 8pm, Union Inn Thursday 23rd Coffee Drinkers – Hostess Mary Griffin Folk Night 9pm Union Inn The Denbury Diary is an independent publication distributed free to residents of Denbury & Torbryan. An online copy is available on our Local Post Office Facebook page and at www.denbury.net. Opening Times If you would like to contact the editor please email [email protected]. Ipplepen Post Office Mon, Tues, Thurs, Frid 9.00am - 5.30pm. Wed 9.00am to 1.00pm. Sat 9.00am to 12.30pm. Broadhempston Post Office Monday - Friday 9.00am to 12 noon. -

The Spinney 2 Orchard Drive, Ipplepen Newton Abbot, Devon TQ12

13 Market Street, Newton Abbot, Devon TQ12 2RL. Tel: 01626 353881 Email: [email protected] REF: DRN00564 The Spinney 2 Orchard Drive, Ipplepen Newton Abbot, Devon TQ12 5QP A detached 2 bedroom bungalow situated in a quiet neighbourhood on the outskirts of Ipplepen within easy walking distance of the village centre. * Entrance Porch* Reception Hallway* Sitting Room* Kitchen* 2 Bedrooms* Bathroom* Utility/Sun Room* uPVC Double Glazing* Single Attached Garage* Front & Rear Gardens* Storage Shed/Summerhouse* Driveway Parking* Far Reaching Views to Dartmoor* Village Location* In Need of Modernisation* GUIDE PRICE £255,000 The Spinney, 2 Orchard Drive, Ipplepen, Newton Abbot, Devon, TQ12 5QP. Situation: The Spinney, 2 Orchard Drive is situated in a quiet neighbourhood on the outskirts of Ipplepen but within easy walking distance of the village centre. This favoured village offers a good range of amenities including a thriving primary school, village shop and popular Inn noted for good food. Ipplepen is also within easy reach of the market towns of Newton Abbot and Totnes both with excellent educational provision, good shopping facilities and mainline stations to London Paddington. Description: A 1970’s semi detached bungalow built of brick and block with colour washed cement rendered walls having some exposed stone work, under a cement tiled pitched roof having plastic facias, soffits, gutters and downpipes. There are uPVC double glazed external windows and doors and flat roofs to the Utility/Sun Room and Garage. The property benefits from enclosed level front and rear gardens with driveway parking for one vehicle leading up to an attached single garage. -

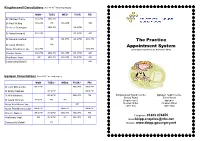

The Practice Appointment System

Kingskerswell Consultations (Nov 2018) * Evening surgery MON * TUES WED* THUR FRI Dr Rachael Prince AM & PM AM & PM Dr Paul Melling AM & PM PM AM & PM PM Dr Helen Burlington AM & PM AM & PM Dr Anna Kennaird AM & PM AM & PM AM Dr Richard Sanford AM AM &PM AM & PM AM & PM The Practice Dr Laura Woollett PM Appointment System Nurse Practitioner Joy Am & PM AM & PM (Information correct as at November 2018) AM & PM AM & PM AM & PM AM & PM AM Practice Nurse Healthcare Ass’t AM AM & PM AM & PM AM & PM AM Community Midwife AM Ipplepen Consultations (Nov 2018) * Evening surgery MON TUES * WEDS THUR * FRI Dr John McCormick AM & PM AM & PM AM & PM Dr Emily Clapham AM & PM AM & PM Dr Phil Windless AM & PM AM & PM PM Kingskerswell Health Centre Ipplepen Health Centre School Road Silver Street AM &PM AM AM Dr Laura Woollett Kingskerswell Ipplepen Newton Abbot Newton Abbot Nurse Practitioner Joy AM TQ12 5DJ TQ12 5QA Nurse Practitioner Louise AM & PM AM & PM AM & PM Practice Nurses AM & PM AM & PM AM & PM AM & PM PM Telephone: 01803 874455 Healthcare Ass’t AM AM & PM AM AM & PM AM Email [email protected] Community Midwife PM Website: www.kkipp.gpsurgery.net APPOINTMENTS IA Appointments The practice tries to match appointment capacity to predicted demand so patients can always Improved Access Service Seven Days a Week be seen promptly. We provide a choice of different types of consultation and can offer appoint- The Practice now offers appointments with GP’s, Practice Nurses and Health Care Assistants, ments for urgent matters on the day and also at least 4 weeks in advance. -

5 Wesley Terrace, East Street, Ipplepen, Devon, TQ12 5SX

5 Wesley Terrace, East Street, Ipplepen, Devon, TQ12 5SX A charming end of terraced cottage, nestled in the heart of the South Hams village of Ipplepen. Newton Abbot 4 miles Totnes 5 miles Exeter 23 miles • Character cottage • Two double bedrooms • Large sitting room with multi-fuel burner • Modern fitted kitchen/diner • Double glazing and gas central heating • Central village location • Much charm and character • No onward chain • Guide price £240,000 01803 865454 | [email protected] Cornwall | Devon | Somerset | Dorset | London stags.co.uk 5 Wesley Terrace, East Street, Ipplepen, Devon, TQ12 5SX SITUATION double bedrooms with a family bathroom. The property This cottage is positioned near the centre of the village of benefits from double glazing and gas fired central heating Ipplepen, which is well served by local amenities. Ipplepen and a very good sized rear garden and outside storage. has a primary school with a Good Ofsted rating, medical centre, village hall, post office and general stores. It also has a public house, two churches, playing fields, tennis club and ACCOMMODATION bowling club. Entrance door leading to sitting room with exposed beams and character feature fireplace with mutli-fuel burning stove Newton Abbot is approximately three and a half miles away which creates a warm ambience. with a more comprehensive selection of attendant amenities including a main line railway station linking to London Steps up to kitchen/dining room with modern fitted floor base Paddington. units and wooden worktops and white ceramic sink with mixer tap. Space for washing machine and fridge. Large In the opposite direction is the picturesque and historic town pantry cupboard with built in shelving. -

Notice of Election

NOTICE OF ELECTION Election of Devon County Councillors on Thursday 6 May 2021 For the Electoral Divisions listed below Electoral Division Number of County Electoral Division Number of County Councillors to be Elected Councillors to be Elected In the District of East Devon In the District of South Hams Axminster One Bickleigh & Wembury One Broadclyst Two Dartmouth & Marldon One Exmouth Two Ivybridge One Exmouth & Budleigh Salterton Coastal One Kingsbridge One Feniton & Honiton One Salcombe One Otter Valley One South Brent & Yealmpton One Seaton & Colyton One Totnes & Dartington One Sidmouth One In the District of Teignbridge Whimple & Blackdown One Ashburton & Buckfastleigh One In the City of Exeter Bovey Rural One Exeter, Alphington & Cowick One Chudleigh & Teign Valley One Exeter, Duryard & Pennsylvania One Dawlish One Exeter, Exwick & St Thomas One Exminster & Haldon One Exeter, Heavitree & Whipton Barton One Ipplepen & The Kerswells One Exeter, Pinhoe & Mincinglake One Kingsteignton & Teign Estuary One Exeter, St David’s & Haven Banks One Newton Abbot North One Exeter, St Sidwells & St James One Newton Abbot South One Exeter, Wearside & Topsham One Teignmouth One Exeter, Wonford & St Loyes One In the District of Torridge In the District of Mid Devon Bideford East One Crediton One Bideford West & Hartland One Creedy, Taw & Mid Exe One Holsworthy Rural One Cullompton & Bradninch One Northam One Tiverton East One Torrington Rural One Tiverton West One In the West Devon Borough Willand & Uffculme One Hatherleigh & Chagford One In the District of North Devon Okehampton Rural One Barnstaple North One Tavistock One Barnstaple South One Yelverton Rural One Braunton Rural One Chulmleigh & Landkey One Combe Martin Rural One Fremington Rural One Ilfracombe One South Molton One Nomination papers may be obtained from the offices of the Deputy Returning Officer for the relevant Council area listed below. -

Devon Branch Newsletter

Devon Branch www.devon-butterflies.org.uk Conservation work for the Heath Fritillary: Lopping off overhanging branches at Lydford Old Railway Reserve COLIN SARGENT Newsletter Issue Number 107 February 2020 Butterfly Devon Branch Conservation Newsletter The Newsletter of Butterfly The Editor may correct errors Conservation Devon Branch in, adjust, or shorten articles if published three times a year. necessary, for the sake of accu- racy, presentation and space available. Of- Copy dates: late December, late April, late ferings may occasionally be held over for a August for publication in February, June, later newsletter if space is short. and October in each year. The views expressed by contributors are not Send articles and images to the Editor necessarily those of the Editor or of Butterfly (contact details back of newsletter). Conservation either locally or nationally. Contents Members’ Day and AGM:- Chair’s report Jonathan Aylett 4 Moth Report Barry Henwood 7 Treasurer’s annual statement of accounts Ray Jones 9 Members’ Day Talks Phil Sterling, Megan Lowe, Andy Barker 10 Silver-studded Blue in Devon in 2019 Lesley Kerry 11 Bob Heckford receives Lifetime Achievement Award 12 Brown Hairstreak eggs at Orley Common 14 Long-tailed Blue at Seaton in 2019 15 Monarch sighting Roger Bristow 15 Night-time Painted Lady Dave Holloway 15 Ashclyst Forest conservation work day, 24th Nov. 2019 Amanda Hunter 16 Entomological crossword Paul Butter 17 Crossword answers Paul Butter 18 John Butter DVD’s for sale 18 Small Tortoiseshell in Devon in summer 2019 18 Spare a thought for grassland 18 Committee and non-committee contact info 19 2 Editorial: 2020 has continued, so far with mild and wet weather. -

The Beacon Mission Community

Beacon Parishes Mission Community Profile Ipplepen with Torbryan, Denbury, Broadhempston and Woodland (Ipplepen and Newton Abbot Deanery) Exeter Diocese Woodland Denbury Broadhempston Torbryan Ipplepen The Beacon Mission Community Beacon Mission Community Profile_Draft V4_171116 Beacon Parishes Mission Community Profile Ipplepen with Torbryan, Denbury, Broadhempston and Woodland Contents 1 Bishop’s Forward ................................................................................................................................................................ 4 2 Executive Summary and Person Profile ............................................................................................................................... 5 2.1 Beacon Parishes Mission Community Profile ................................................................................................................ 5 2.2 The Parishes .................................................................................................................................................................. 5 2.2.1 Ipplepen .................................................................................................................................................................... 5 2.2.2 Holy Trinity, Torbryan ............................................................................................................................................... 6 2.2.3 Denbury ................................................................................................................................................................... -

Draft Plan April 2020

Ipplepen Neighbourhood Development Plan (2020- 2040) Draft Plan April 2020 BLANK PAGE 2 Foreward Thank you to all members of the steering group who have given their time and contributions in helping to prepare this Ipplepen Neighbourhood Plan. The formulation of this draft plan has been led by members of our local community, overseen by the Parish Council and guided by our consultant from Teignplanning. A particular thank you to the Teignbridge Neighbourhood planning officer David Kiernan for advising us in the preparation of the plan. Our objective from the outset (just over 3 years ago) was to provide a sustainable community -safeguarding the past, improving the present and shaping the future. This can be summarised by the 6 key issues raised by the steering group: namely ... future developments, employment, character and appearance, car parking, accessibility and community facilities. These form the basis of our vision for the Neighbourhood Plan. It was also our intention, if possible, to allocate potential sites for any future residential and employment development, thus enabling parishioners to have a say over where development goes and what it looks like rather than leaving it to the local district council. We are hopeful that you will be able to both contribute to, and support, the continued development and final adoption of this Neighbourhood Plan going forward. Our Parish have been praised In the past by local council Representatives, following “Road shows“ held in the village, for our response and willingness to engage in this process. So a big thank you to all Parishioners - it reflects the pride taken by so many in being members of Ipplepen Parish community. -

Or the Anti@Ities and Istofqr of the Borough of Ashburton in the County

OR THE ’ ]A N T I @ I T I E S A N D fi I S T O FQr O F T H E BOROU GH OF A SHBU RTON I N THE O N OF V N D HE C U TY DE O , A N OF T ’ a s n hlandd w - fi rishe of fi n the mnnr a nd fi ic ki ngtun . A D P (ITS NCIENT E ENDENCIES) , WITH A MINUTE DESCRIPTION OF THEIR RESPECTIVE a d v fi n am a a a fi z 111 “mm, n i fih gfl wan g mm z $ E E S C O L E O F S H E B E T O N f K I f R , T O GETHER WITH A N ACCOUNT OF SEVERAL OF THE ‘ A DJ A C E NT M A NO RS HU RC HES C , C OMPILED FROM VARIO US AUTHENTIC S OURCES , 0 t B s . K. n Re . CH E THY E l at e M . 8 2 d y A RL S W OR , q , g A SHBURTON I HER EA ST STREET B. D I R D B L . VA R ER, PRNTE A N PU L S , , MDCCCLXXV . ’ !ENTERED AT STATIONER S BA LL ] : M m 1 , q , E RRA T A . Chill dr n e read Children . Dec h er ed D i e yp ec ph red . Ogre Ogee , Bar ge Burgi . r i sh o Pa n er s . $ 1 Parishioners Di lli en e D g c iligence .