Dever Joseph MRP ( .Pdf )

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

US 1 from Kendall to I-95: Final Summary Report

STATE ROAD (SR) 5/US 1/DIXIE HIGHWAY FROM SR 94/SW 88 STREET/ KENDALL DRIVE TO SR 9/I-95 MIAMI-DADE COUNTY, FLORIDA FDOT FINANCIAL PROJECT ID: 434845-1-22-01 WWW.FDOTMIAMIDADE.COM/US1SOUTH March 2019 Final Summary Report ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Thank you to the many professionals and stakeholders who participated in and contributed to this study. From the communities along the corridor to the members of the Project Advisory Team, everyone played a crucial role in forming the results and conclusions contained in this study. 2 STATE ROAD (SR) 5/US 1/DIXIE HIGHWAY FROM SR 94/SW 88 STREET/KENDALL DRIVE TO SR 9/I-95 This report compiles the results of the State Road (SR) 5/US 1/ Dixie Highway from SR 94/SW 88 Street/Kendall Drive to SR 9/I-95 Corridor Study and includes: › Findings from the study › Recommendations for walking, bicycling, driving, and transit access needs along US 1 between Kendall Drive and I-95 › Next steps for implementing the recommendations This effort is the product of collaboration between the Florida Department of Transportation District Six and its regional and local partners. FDOT and its partners engaged the community at two critical stages of the study – during the identification of issues and during the development of recommendations. The community input helped inform the recommended strategies but the collaboration cannot stop here. Going from planning to implementation will take additional coordination and, in some instances, additional analysis. FDOT is able and ready to lead the effort but will continue seeking the support of community leaders, transportation and planning organizations, and the general public! To learn more, please read on and visit: www.fdotmiamidade.com/us1south WWW.FDOTMIAMIDADE.COM/US1SOUTH 3 CONTENTS 1. -

On the Move... Miami-Dade County's Pocket

Guide Cover 2013_English_Final.pdf 1 10/3/2013 11:24:14 AM 111 NW First Street, Suite 920 Miami, FL 33128 tel: (305) 375-4507 fax: (305) 347-4950 www.miamidade.gov/mpo C M On the Y CM MY Move... CY CMY K Miami-Dade County’s Pocket Guide to Transportation Metropolitan Planning Organization (MPO) 4th Edition Table of Contents Highway Information Florida Department of Transportation (FDOT) p. 1 FDOT’s Turnpike Enterprise p. 2 Florida Highway Patrol p. 2 95 Express Lanes p. 3 Miami-Dade Expressway Authority (MDX) p. 4 SunPass® p. 5 511-SmarTraveler p. 5 Road Rangers p. 5 SunGuide® Transportation Management Center p. 6 Miami-Dade Public Works and Waste p. 7 Management Department Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV) p. 8 Driving and Traffic Regulations p. 8 Three Steps for New Florida Residents p. 9 Drivers License: Know Before You Go p. 9 Vehicle Registration p. 10 Locations and Hours of Local DMV Offices p. 10-11 Transit Information Miami-Dade Transit (MDT) p. 12 Metrobus, Metrorail, Metromover p. 12 Fares p. 13 EASY Card p. 13 Discount EASY Cards p. 14-15 Obtaining EASY Card or EASY Ticket p. 15 Transfers p. 16-17 Park and Ride Lots p. 17-18 Limited Stop Route/Express Buses p. 18-19 Special Transportation Services (STS) p. 20 Special Event Shuttles p. 21 Tax-Free Transit Benefits p. 21 I Transit Information (Continued) South Florida Regional Transportation Authority p. 22 (SFRTA) / TriRail Amtrak p. 23 Greyhound p. 23 Fare & Schedule Information p. 24 Local Stations p. -

Transit-Oriented Hyperdensity in Miami: Year 2100 Kenner N

Policy Memorandum Tropical Dense[city]:Transit-Oriented Hyperdensity in Miami: Year 2100 Kenner N. Carmody, M.Des Energy & Environments 2019 Problem: This research aims to visualize and better understand future required housing stock necessary to accommodate displaced populations in Miami’s Allapattah neighborhood affected by sea level rise and resultant tidal inundation by the year 2100 (NOAA Office for Coastal Management). Property data, local geography and NOAA sea-level rise projections within this time-scale are used in order to propose greater density in Miami due to lost surface area. This study evaluates the existing spatial capacity and density distribution under current zoning policy, Miami 21. This study reveals that the current zoning code, overlay districts, and Neighborhood Development Zones (NDZ) within the population catchment area of Allapattah are maladaptive. - The spatial analysis in this research assumes a residential occupancy of 1 person per 450 square feet (41.8m2), and floor to floor heights of 14’-0” (4.2m). - The criteria for this displacement assumes intracity relocation within Miami’s urban core, and excludes populations affected outside of the target study area of Allapattah. - This model assumes relocation within a population catchment area in Allapattah at elevations of 6’-0” above sea level and assumes density increases along Miami’s legacy Metrorail system. - This study excludes future population growth from the required future housing scenario. Figures Housing: - Total Population in Allapattah: 58,978 (2010 Census Data); 62,929 (2017 Estimate) - Total Housing Units: 22,255 - Unit Mix: Studio: 3% 1-Bedroom: 8%; 2-Bedroom: 35%; 3-Bedroom: 20%; 4-Bedroom: 17%; 5-Bedroom: 7%; 6-Bedroom: 4%; > 6% - The majority of housing stock in Allapattah predates 1975 and is poorly suited to its geography and climate. -

Model-City-District-Regulations.Pdf

Approved Mayor Agenda Item No. Veto __________ Override __________ ORDINANCE NO. ______________ ORDINANCE RELATING TO ZONING AND OTHER LAND DEVELOPMENT REGULATIONS; PROVIDING FOR THE MODEL CITY URBAN CENTER DISTRICT; CREATING SECTIONS 33-284.99.40 THROUGH 33-284.99.46 OF THE CODE OF MIAMI-DADE COUNTY (CODE); AMENDING SECTION 33C-7 OF THE CODE; PROVIDING SEVERABILITY, INCLUSION IN THE CODE AND AN EFFECTIVE DATE BE IT ORDAINED BY THE BOARD OF COUNTY COMMISSIONERS OF MIAMI- DADE COUNTY, FLORIDA: Section 1. Section 33-284.99.40 of the Code of Miami-Dade County, Florida, is hereby created as follows: ARTICLE XXXIII (R) MODEL CITY URBAN CENTER DISTRICT (MCUCD) Sec. 33-284.99.40. Purpose, intent and applicability. A. The regulations contained in this chapter and Chapter 18A, Landscape Code, Code of Miami-Dade County, Florida, shall apply to this article, except as otherwise added to or modified herein. B. The Illustrative Master Plan (Figure 1) illustrates the citizens’ vision and may be used to interpret this article. Where the Illustrative Master Plan conflicts with the provisions of this article, the provisions of this article shall govern. C. Figure 1 also shows the boundaries of the Model City Urban Center District (MCUCD), as well as the boundaries of the Designated Urban Center. The MCUCD’s Designated Urban Center shall consist of the areas designated as being the Core and Center Sub-districts on the Sub-districts Plan in Sec. 33- 284-99.43 of this code. As provided in Standard Urban Center District Regulations, the Workforce Housing requirement shall Agenda Item No. -

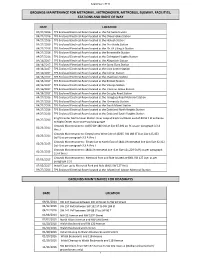

Grounds Maintenance for Metrorail, Metromover, Metrobus, Busway, Facilities, Stations and Right of Way

Attachment 8F14 GROUNDS MAINTENANCE FOR METRORAIL, METROMOVER, METROBUS, BUSWAY, FACILITIES, STATIONS AND RIGHT OF WAY DATE LOCATION 04/27/2016 TPS Enclosed Electrical Room located at the Palmetto Station 04/27/2016 TPS Enclosed Electrical Room located at the Okeechobee Station 04/27/2016 TPS Enclosed Electrical Room located at the Hialeah Station 04/27/2016 TPS Enclosed Electrical Room located at the Northside Station 04/27/2016 TPS Enclosed Electrical Room located at the Dr. M L King Jr Station 04/27/2016 TPS Enclosed Electrical Room located at the Brownsville Station 04/27/2016 TPS Enclosed Electrical Room located at the Earlington Heights Station 04/16/2017 TPS Enclosed Electrical Room located at the Allapattah Station 04/16/2017 TPS Enclosed Electrical Room located at the Santa Clara Station 04/16/2017 TPS Enclosed Electrical Room located at the Civic Center Station 04/16/2017 TPS Enclosed Electrical Room located at the Culmer Station 04/16/2017 TPS Enclosed Electrical Room located at the Overtown Station 04/16/2017 TPS Enclosed Electrical Room located at the Brickell Station 04/16/2017 TPS Enclosed Electrical Room located at the Vizcaya Station 04/16/2017 TPS Enclosed Electrical Room located at the Coconut Grove Station 04/16/2017 TPS Enclosed Electrical Room located at the Douglas Road Station 04/27/2016 TPS Enclosed Electrical Room located at the Douglass Road Metrorail Station 04/27/2016 TPS Enclosed Electrical Room located at the University Station 04/27/2016 TPS Enclosed Electrical Room located at the South Miami Station 04/27/2016 TPS Enclosed Electrical Room located at the Dadeland North Heights Station 04/27/2016 TPS Enclosed Electrical Room located at the Dadeland South Heights Station Knight Center Metromover Station Inner Loop at Electrical Room east of 88 SE 4 St entrance 04/27/2016 to Night Center main tower parking garage Grounds Maintenance to 10235 SW 186 St (Lot Size 87,692 sq. -

Planning Committee Meeting

Florida Housing Finance Corporation 7/20/12 Planning Committee 1. Review of development costs per unit 2. Funding of TODs 3. Demonstration of highest Florida job creation 4. Funding of & Preference for RA Levels 1-3 (Preservation) 5. Universal Design & Visitability Features 6. Resident Programs FHFC-Financed Developments Located Near MetroRail Stations in Miami-Dade County Station Name/Development Name Year Funded Units 2011 UAC Deals ranked for funding are highlighted Palmetto Station (0 applied) No existing developments within 0.5 miles Okeechobee Station (0 applied) No existing developments within 0.5 miles Hileah Station (0 applied) No existing developments within 0.5 miles Tri-Rail/MetroRail Station (0 applied) *Station Area overlaps with Northside No existing developments within 0.5 miles Northside Station (2 applied; 0 awarded) *Station area overlaps with Trirail/MetroRail No existing developments within 0.5 miles Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Station (0 applied) *Station area overlaps with Brownsville No existing developments within 0.5 miles Brownsville Rail Station (2 applied; 0 awarded) *Station area overlaps with Dr. MLK Jr. Everett Steward Sr. Village (E) 2007 96 Brownsville Transit Village II (E) 2008 100 Brownsville Transit Village III (E) 2010 103 Brownsville Transit Village IV (F) 2010 102 Mildred and Claude Pepper Towers (E-pres) 2005 150 Ward Tower Assisted Living Facility (E-ALF) 2005 100 Earlington Heights Station (7 applied; 0 awarded) *Station area overlaps with Allapattah Esmeralda Bay (E) 2010 96 Friendship Tower -

Analysis and Recommendation

DEPARTMENTAL INPUT CONTRACT/PROJECT MEASURE ANALYSIS AND RECOMMENDATION New OTR Sole Source Bid Waiver Emergency Previous Contract/Project No. Contract RFP-01515 Re-Bid Other LIVING WAGE APPLIES: YES NO RFP-01673 90 0 Requisition No./Project No.: TERM OF CONTRACT YEAR(S) WITH YEAR(S) OTR Requisition /Project Title: Development of Vizaya Station Property Description: RFP process to procure a developer to finance and construct a mixed use (commercial/possible residential) complex on County property with a revenue sharing agreement. There will be no County funding contributions for this project. The property has a federal interest. Issuing Department: DTPW Contact Person: Javier Bustamante Phone: 786-469-5244 Estimate Cost: Revenue Generating GENERAL FEDERAL OTHER Funding Source: n/a ANALYSIS Commodity Codes: 57863 91889 92561 Contract/Project History of previous purchases three (3) years Check here if this is a new contract/purchase with no previous history. EXISTING 2ND YEAR 3RD YEAR Contractor: Small Business Enterprise: Contract Value: $ $ $ Comments: Continued on another page (s): YES NO RECOMMENDATIONS Set-aside Sub-contractor goal Bid preference Selection factor SBE Basis of recommendation: Date sent to SBD: 09/17/2020 Signed: Brian Webster Date returned to DPM: Revised April 2005 REQUEST FOR PROPOSALS (RFP) NO. 01673 FOR DEVELOPMENT OF VIZCAYA STATION PROPERTY ISSUED BY MIAMI-DADE COUNTY: Internal Services Department, Strategic Procurement Division for Department of Transportation and Public Works MIAMI-COUNTY CONTACT FOR THIS SOLICITATION: Brian Webster, Procurement Contracting Officer 111 NW 1st Street, Suite 1300, Miami, Florida 33128 E-mail: [email protected] PROPOSALS DUE: On the date and at the time specified in BidSync. -

Rapid Transit Project Development & Environment (PD&E) Study 1000 NW 111Th Avenue Miami, FL 33172

FACT SHEET FM# 438076-1-22-01 SR 9 / SR 817 / NW 27th Avenue www.fdotmiamidade.com/27thAvenueRapidTransit Rapid Transit Project Development & Environment (PD&E) Study 1000 NW 111th Avenue Miami, FL 33172 Like www.facebook.com/MyFDOTMiami Follow www.twitter.com/MyFDOT_Miami Subscribe www.youtube.com/user/MyFDOTMiami Stay Informed: On the Inside: Project Website: ► Project Overview and Limits www.fdotmiamidade.com/27thAvenueRapidTransit ► Study Objective Get Involved: ► What is Rapid Transit? Contact: ► Public Involvement Program FDOT Project Manager Joan Shen, Ph.D., P.E., PTOE ► Project Goals email: [email protected] ► Project Schedule telephone: 305.640.7557 ► Project Map Public Information Specialist Ann Pope email: [email protected] telephone: 305.321.6011 SR 9 / SR 817 / NW 27th Avenue Rapid Transit Corridor PD&E Study FACT SHEET Overview and Limits The Florida Department of Transportation (FDOT) is conducting a Project Development and Environment (PD&E) Study for the implementation of rapid Project Goals transit along SR 9/SR 817/NW 27th Avenue (referred to as the NW 27th Avenue ► Maximize mobility by offering an alternate Corridor). The PD&E study limits are as follows and illustrated in the map below: transportation mode with competitive travel times, • NW 27th Avenue from NW 215th Street to NW 38th Street which improves the corridor’s people-carrying capacity. • SR 112 from NW 27th Avenue to the Miami Intermodal Center ► Enhance connectivity with local and other regional The NW 27th Avenue Corridor is one of six corridors that comprise the Strategic transit systems that improves transportation system Miami Area Rapid Transit (SMART) Plan as adopted by the Miami-Dade efficiency. -

Vizcaya Metrorail Station 3201 SW 1St Avenue, Miami, Florida

Vizcaya Metrorail Station 3201 SW 1st Avenue, Miami, Florida Park & Ride Lot Utilization 2011-2015 Annual Average Growth Rate – 1.5% 2015 Total Spaces – 120 2015 Percent Occupancy – 52% Bicycle Parking 2015 Total Spaces – 10 U-Style Racks Transit station 2015 Percent Occupancy – 10% Vizcaya station Metrorail Ridership 2011-2015 boardings/alightings Average Growth Rate Weekday – 4.5% Saturday – 5.8% Sunday – 5.8% 2015 Average daily boardings/alightings Weekday – 1,515 Saturday – 710 Sunday – 526 Bus Stop Ridership 2011-2015 Annual Average Growth Rate Weekday – 10.8% Saturday – 6.8% Sunday – 7.2% 2015 Average daily boardings/alightings Weekday – 2,095 Saturday – 903 Sunday – 728 Location Map Station Bus Route Information (2014) Route Span of Service Peak Off-Peak Evening Overnight Saturday Sunday 12 4:30am - 12:30am 30 30 45 n/a 40 40 17 4:30am - 1:00am 30 30 60 n/a 30 30 24 5:00am - 12:45am n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a 500 12:30am - 5:45am n/a n/a n/a 60 60ovn 60ovn Page 1 of 46 Vizcaya Metrorail Station: Field Observations The Vizcaya Metrorail Station is well connected to the neighborhood on the west side of US-1. There is sidewalk access to/from neighborhood streets including SW 1st Avenue and SW 34th Road. The station also has on-site pedestrian facilities including sidewalks from the SW 1st Avenue to the station and a pedestrian plaza. Access to the east side of US-1 is provided by an overpass. There are no bike lanes accessing the station from the neighborhood but the station is directly connected to the M- Path providing short and longer distance pedestrian/bicycle access. -

Hillsborough Area Regional Transit (HART), Ybor Streetcar 4 System Description System Map Station Development Opportunity Summary Station Profiles

TECHNICAL MEMORANDUM NUMBER TWO£ INVENTORY OF FLORIDA STATION DEVELOPMENT SITES AND OPPORTUNITIES Enabling StaJion Area Development in Florida: Towards More Cost Effective Rail Transit Investment for Office of Public Transportation Florida Department ofTransportation 605 Suwanee Street (MS 26) Tallahassee, Florida 32399-0450 TECHNICAL MEMORANDUM NUMBER TWO: INVENTORY OF FLORIDA STATION DEVELOPMENT SITES AND OPPORTUNITIES Enabling Station Area Developnumt in Florida: Towards More Cost Effective Rail Transit Investment for Olfoce of Public Tnwponation Florida Depanment of Transportation 60S SuWOIUlM S~rnet (MS 26) Tallaluwcc, Florida 32399-0450 through Center for Urban Transportation Re•eareb College of Engineering, University of South Florida 4202 B. Fowler Avenue, ENB 100 Tampa, PL 33620·5350 (813) 974-3120, Fax (813) 974-5168 by Tnwit Solutions 4612 Evanston A venue North StanJe, WA 98103 (206) 632·3443, Fax (206) 632·3444 Email: [email protected] March 2000 Project Manager Ronald C. Sb<ck Pl'()ject Staff SooUPlaee TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 1 Hillsborough Area Regional Transit (HART), Ybor Streetcar 4 System Description System Map Station Development Opportunity Summary Station Profiles JacksonviUe Transportation Authority (JTA), Skyway 30 System Description System Map Station Development Opportunity Summary Station Profiles Metro Dade Transit Agency (MDTA), Metrorail 48 System Description System Map Station Development Opportunity Summary Station Profiles Metro Dade Transit Agency (MDTA), Metromover 92 System Description System Map Station Development Opportunity Summary Station Profiles Tri County Commuter Railroad Authority, Tri Rail 100 System Description System Map Station Development Opportunity Summary Station Profiles Resources 138 INTRODUCTION Perspective. Station area development requires stations. With each new rail iransit system constructed in the United States, station area development appears to becoming a more important aspect of rail transit investment. -

Potential Issues Should Be Considered Before the Decision of Conversion Is Made

Evaluation of the Conversion for Northbound Bus Route from SW 31st Road to SW 32nd Road Draft Final Report Prepared for Miami-Dade Transit Prepared by Larry Hagen, P.E., PTOE (PI) Pei-Sung Lin, Ph.D., P.E. (Co-PI) Sachin Rai, E.I. Center for Urban Transportation Research University of South Florida, Tampa December 20, 2005 “Evaluation of the Conversion for Northbound Bus Route from SW 31st Road to SW 32nd Road” BACKGROUND Miami-Dade Transit (MDT) is concerned about the noise and safety impacts of northbound Metro bus operations on SW 31st Road. The concern was originated from residents’ complaints regarding traffic noise generated by MDT buses along SW 31st Road, a narrow residential street, between the Vizcaya Metrorail Station and Coral Way. To resolve residents’ complaints, it has been requested that MDT investigate re-routing buses exiting Vizcaya Metrorail station, from SW 31st Road onto SW 32nd Road. In November 2004, a qualitative assessment report [1] for Coral Way at SW 32nd Road was conducted by Marlin Engineering. Based on the recommendation from Marlin Engineering, MDT has requested that the Center for Urban Transportation Research (CUTR) at the University of South Florida perform further analyses to evaluate bus operations with the conversion of SW 32 Road from a one-way to a two-way street, and provide necessary recommendations. Evaluation of the impacts of moving northbound bus routes from SW 31st Road to SW 32nd Road to reduce the impact of bus noise on the adjacent residential area involves environmental, traffic operations, bus safety, and bus routing issues. -

The Underline

(c) 2016 James Corner Field Operations Hammock Trail THE UNDERLINE PHASE II PUBLIC MEETING MAY 25, 2021 Please enter your home Zip Code? ⓘ Start presenting to display the poll results on this slide. AGENDA Welcome, David Jones, Miami-Dade County Department of Transportation and Public Works (DTPW) Introductions • From the Office of Miami-Dade County Commissioner Eileen Higgins, Dist. 5 and Chair of the Transportation, Mobility and Planning Committee: • Nancy Jackson, District Director • Nora Viñas, District Coordinator The Underline, Meg Daly, Founder Friends of The Underline Meeting goals, Irene Hegedus, MDC DTPW Transit Enhancements Phase 2, Irene Hegedus and Design/Build Team • Introduce Design Team • Mario Rojas, P.E. • Ken Gardner, ASLA, LEED AP • Overview 3 plaza areas • Amenities Questions, comments, and answers 3 GUIDELINES To maintain a safe and respectable forum, we ask that participants abide by the following guidelines during the designated Q&A portion. Violators are subject to removal from meeting. ▪ All participants’ microphones will remain muted, unless it is their turn to speak ▪ Raise hand to ask a question ▪ Profanity or inappropriate language will not be tolerated ▪ When speaking, be mindful of background noises ▪ Speaking time is limited 4 THE UNDERLINE DISCOVERY 2013 5 PUBLIC PRIVATE PARTNERSHIP COMMUNITY & MIAMI-DADE COUNTY Photo courtesy Brickell Run Club 6 Get Visual UNIVERSITY OF MIAMI SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE 7 PUBLIC MEETINGS IN-PERSON AND ONLINE SURVEYS 8 THE UNDERLINE WILL BE A MULTI-MODAL CORRIDOR, MIAMI’S