Marty Glickman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cubs Win the World Series!

Can’t-miss listening is Pat Hughes’ ‘The Cubs Win the World Series!’ CD By George Castle, CBM Historian Posted Monday, January 2, 2017 What better way for Pat Hughes to honor his own achievement by reminding listeners on his new CD he’s the first Cubs broadcaster to say the memorable words, “The Cubs win the World Series.” Hughes’ broadcast on 670-The Score was the only Chi- cago version, radio or TV, of the hyper-historic early hours of Nov. 3, 2016 in Cleveland. Radio was still in the Marconi experimental stage in 1908, the last time the Cubs won the World Series. Baseball was not broadcast on radio until 1921. The five World Series the Cubs played in the radio era – 1929, 1932, 1935, 1938 and 1945 – would not have had classic announc- ers like Bob Elson claiming a Cubs victory. Given the unbroken drumbeat of championship fail- ure, there never has been a season tribute record or CD for Cubs radio calls. The “Great Moments in Cubs Pat Hughes was a one-man gang in History” record was produced in the off-season of producing and starring in “The Cubs 1970-71 by Jack Brickhouse and sidekick Jack Rosen- Win the World Series!” CD. berg. But without a World Series title, the commemo- ration featured highlights of the near-miss 1969-70 seasons, tapped the WGN archives for older calls and backtracked to re-creations of plays as far back as the 1930s. Did I miss it, or was there no commemorative CD with John Rooney, et. -

Handbook of Sports and Media

Job #: 106671 Author Name: Raney Title of Book: Handbook of Sports & Media ISBN #: 9780805851892 HANDBOOK OF SPORTS AND MEDIA LEA’S COMMUNICATION SERIES Jennings Bryant/Dolf Zillmann, General Editors Selected titles in Communication Theory and Methodology subseries (Jennings Bryant, series advisor) include: Berger • Planning Strategic Interaction: Attaining Goals Through Communicative Action Dennis/Wartella • American Communication Research: The Remembered History Greene • Message Production: Advances in Communication Theory Hayes • Statistical Methods for Communication Science Heath/Bryant • Human Communication Theory and Research: Concepts, Contexts, and Challenges, Second Edition Riffe/Lacy/Fico • Analyzing Media Messages: Using Quantitative Content Analysis in Research, Second Edition Salwen/Stacks • An Integrated Approach to Communication Theory and Research HANDBOOK OF SPORTS AND MEDIA Edited by Arthur A.Raney College of Communication Florida State University Jennings Bryant College of Communication & Information Sciences The University of Alabama LAWRENCE ERLBAUM ASSOCIATES, PUBLISHERS Senior Acquisitions Editor: Linda Bathgate Assistant Editor: Karin Wittig Bates Cover Design: Tomai Maridou Photo Credit: Mike Conway © 2006 This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2009. To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk. Copyright © 2006 by Lawrence Erlbaum Associates All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by photostat, microform, retrieval system, or any other means, without prior written permission of the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Handbook of sports and media/edited by Arthur A.Raney, Jennings Bryant. p. cm.–(LEA’s communication series) Includes bibliographical references and index. -

The Berlin Olympics: Sports, Anti-Semitism, and Propaganda in Nazi Germany Nathan W

Student Publications Student Scholarship Spring 2016 The Berlin Olympics: Sports, Anti-Semitism, and Propaganda in Nazi Germany Nathan W. Cody Gettysburg College Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship Part of the European History Commons, Political History Commons, Social History Commons, and the Sports Studies Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Cody, Nathan W., "The Berlin Olympics: Sports, Anti-Semitism, and Propaganda in Nazi Germany" (2016). Student Publications. 434. https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship/434 This is the author's version of the work. This publication appears in Gettysburg College's institutional repository by permission of the copyright owner for personal use, not for redistribution. Cupola permanent link: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship/ 434 This open access student research paper is brought to you by The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The uC pola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Berlin Olympics: Sports, Anti-Semitism, and Propaganda in Nazi Germany Abstract The aN zis utilized the Berlin Olympics of 1936 as anti-Semitic propaganda within their racial ideology. When the Nazis took power in 1933 they immediately sought to coordinate all aspects of German life, including sports. The process of coordination was designed to Aryanize sport by excluding non-Aryans and promoting sport as a means to prepare for military training. The 1936 Olympic Games in Berlin became the ideal platform for Hitler and the Nazis to display the physical superiority of the Aryan race. However, the exclusion of non-Aryans prompted a boycott debate that threatened Berlin’s position as host. -

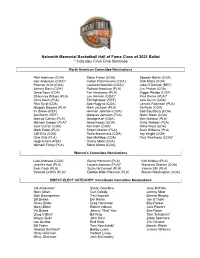

Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame Class of 2021 Ballot * Indicates First-Time Nominee

Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame Class of 2021 Ballot * Indicates First-Time Nominee North American Committee Nominations Rick Adelman (COA) Steve Fisher (COA) Speedy Morris (COA) Ken Anderson (COA)* Cotton Fitzsimmons (COA) Dick Motta (COA) Fletcher Arritt (COA) Leonard Hamilton (COA)* Jake O’Donnell (REF) Johnny Bach (COA) Richard Hamilton (PLA) Jim Phelan (COA) Gene Bess (COA) Tim Hardaway (PLA) Digger Phelps (COA) Chauncey Billups (PLA) Lou Henson (COA)* Paul Pierce (PLA)* Chris Bosh (PLA) Ed Hightower (REF) Jere Quinn (COA) Rick Byrd (COA) Bob Huggins (COA) Lamont Robinson (PLA) Muggsy Bogues (PLA) Mark Jackson (PLA) Bo Ryan (COA) Irv Brown (REF) Herman Johnson (COA) Bob Saulsbury (COA) Jim Burch (REF) Marques Johnson (PLA) Norm Sloan (COA) Marcus Camby (PLA) George Karl (COA) Ben Wallace (PLA) Michael Cooper (PLA)* Gene Keady (COA) Chris Webber (PLA) Jack Curran (COA) Ken Kern (COA) Willie West (COA) Mark Eaton (PLA) Shawn Marion (PLA) Buck Williams (PLA) Cliff Ellis (COA) Rollie Massimino (COA) Jay Wright (COA) Dale Ellis (PLA) Bob McKillop (COA) Paul Westhead (COA)* Hugh Evans (REF) Danny Miles (COA) Michael Finley (PLA) Steve Moore (COA) Women’s Committee Nominations Leta Andrews (COA) Becky Hammon (PLA) Kim Mulkey (PLA) Jennifer Azzi (PLA) Lauren Jackson (PLA)* Marianne Stanley (COA) Swin Cash (PLA) Suzie McConnell (PLA) Valerie Still (PLA) Yolanda Griffith (PLA)* Debbie Miller-Palmore (PLA) Marian Washington (COA) DIRECT-ELECT CATEGORY: Contributor Committee Nominations Val Ackerman* Simon Gourdine Jerry McHale Marv -

Spitting in the Soup Mark Johnson

SPITTING IN THE SOUP INSIDE THE DIRTY GAME OF DOPING IN SPORTS MARK JOHNSON Copyright © 2016 by Mark Johnson All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic or photocopy or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher except in the case of brief quotations within critical articles and reviews. 3002 Sterling Circle, Suite 100 Boulder, Colorado 80301-2338 USA (303) 440-0601 · Fax (303) 444-6788 · E-mail [email protected] Distributed in the United States and Canada by Ingram Publisher Services A Cataloging-in-Publication record for this book is available from the Library of Congress. ISBN 978-1-937715-27-4 For information on purchasing VeloPress books, please call (800) 811-4210, ext. 2138, or visit www.velopress.com. This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper). Art direction by Vicki Hopewell Cover: design by Andy Omel; concept by Mike Reisel; illustration by Jean-Francois Podevin Text set in Gotham and Melior 16 17 18 / 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 CONTENTS Introduction ...................................... 1 1 The Origins of Doping ............................ 7 2 Pierre de Coubertin and the Fair-Play Myth ...... 27 3 The Fall of Coubertin’s Ideal ..................... 41 4 The Hot Roman Day When Doping Became Bad ..................................... 55 5 Doping Becomes a Crime........................ 75 6 The Birth of the World Anti-Doping Agency ..... 85 7 Doping and the Cold War........................ 97 8 Anabolic Steroids: Sports as Sputnik .......... -

Jews, Sports and Society

Jews, Sports and Society Dedication. Countless hours of commitment. Sacrifice. Rising to the challenges of adversity. Maximizing one’s natural talents. A religiously-infused life and the endeavor of sports have much in common, though often come into conflict. We share with you the latest issue of YU Ideas, “Jews, Sports and Society,” featuring essays from Yeshiva University faculty and staff, and invite you to reflect on the myriad ways in which Judaism and sports have intersected, both historically and in our contemporary era. We dedicate this issue in memory of Bob Tufts, former Sy Syms School of Business Professor and former major league baseball pitcher, who boldly and passionately lived a life balancing faith and passion for sport. JEWS IN SPORTS: Something to Think About and Appreciate Joe Bednarsh Director of Athletics, Yeshiva University There are so many jokes a doctor,” “my son is a lawyer,” “my son owns a business” associated with the phrase over “my son plays college ball”? “Jews in Sports.” Most use the typical self-deprecating, Was it about education? Think about how culturally good-natured Jewish important education has been to our people even before humor that sustains our people, but inherent in those (self) the modern standardized schooling of today. Did our jabs is likely a feeling that, as Jews, we just don’t have the families reason that sports participation would take too goods to be at the top of the game. Or maybe it’s just “pas much time away from their young ones’ studies and nisht,” not for us—we need to put more effort into our therefore negatively impact their ability to make life better futures and the futures our families. -

Miscellaneous

MISCELLANEOUS Phoenix Municipal Stadium, the A’s Spring Training home OAKLAND-ALAMEDA COUNTY COLISEUM FRONT OFFICE 2009 ATHLETICS REVIEW The Oakland-Alameda County Coliseum plays host to concerts, conventions and other large gatherings in addi- tion to serving as the home for the Oakland Athletics and Oakland Raiders. The A’s have used the facility to its advantage over the years, posting the second best home record (492-318, .607) in the Major Leagues over the last 10 seasons. In 2003, the A’s set an Oakland record for home wins as they finished with a 57-24 (.704) record in the Coliseum, marking the most home wins in franchise history since 1931 RECORDS when the Philadelphia Athletics went 60-15 at home. In addition, two of the A’s World Championships have been clinched on the Coliseum’s turf. The Coliseum’s exceptional sight lines, fine weather and sizable staging areas have all contributed to its popularity among performers, promoters and the Bay Area public. The facility is conveniently located adjacent to I-880 with two exits (Hegenberger Road/66th Avenue) leading directly to the complex. Along with the Oracle Arena, which is located adjacently, it is the only major entertainment facility with a dedicated stop on the Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) system. The Oakland International Airport is less than a two-mile drive from the Coliseum with shuttle service to several local hotels and restaurants. In October of 1995, the Coliseum HISTORY began a one-year, $120 renovation proj- ect that added 22,000 new seats, 90 luxury suites, two private clubs and two OAKLAND-ALAMEDA COUNTY COLISEUM state-of-the-art scoreboards. -

Jim Brown, Ernie Davis and Floyd Little

The Ensley Athletic Center is the latest major facilities addition to the Lampe Athletics Complex. The $13 million building was constructed in seven months and opened in January 2015. It serves as an indoor training center for the football program, as well as other sports. A multi- million dollar gift from Cliff Ensley, a walk-on who earned a football scholarship and became a three-sport standout at Syracuse in the late 1960s, combined with major gifts from Dick and Jean Thompson, made the construction of the 87,000 square-foot practice facility possible. The construction of Plaza 44, which will The Ensley Athletic Center includes a 7,600 tell the story of Syracuse’s most famous square-foot entry pavilion that houses number, has begun. A gathering area meeting space and restrooms. outside the Ensley Athletic Center made possible by the generosity of Jeff and Jennifer Rubin, Plaza 44 will feature bronze statues of the three men who defi ne the Legend of 44 — Jim Brown, Ernie Davis and Floyd Little. Syracuse defeated Minnesota in the 2013 Texas Bowl for its third consecutive bowl victory and fi fth in its last six postseason trips. Overall, the Orange has earned invitations to every bowl game that is part of the College Football Playoff and holds a 15-9-1 bowl record. Bowl Game (Date) Result Orange Bowl (Jan. 1, 1953) Alabama 61, Syracuse 6 Cotton Bowl (Jan. 1, 1957) TCU 28, Syracuse 27 Orange Bowl (Jan. 1, 1959) Oklahoma 21, Syracuse 6 Cotton Bowl (Jan. 1, 1960) Syracuse 23, Texas 14 Liberty Bowl (Dec. -

Education Committee Holds Conference Church Tower Crumbling

) fordham university, new york Education Committee Vigil Holds Conference Held Leadership Responsibility and Multi Culturalism Discussed By TOM MKLI.4NA By ELENA DB1ORE ing^" All of these workshops touched on the con- counseling center at St. John's University, and Students mid (acuity of I-onilMin UIMVMM The Education Committee and the Commit- cepts of race/ethnic groups, prejudice, and Gail Hawkins, director of students activities at ty, ulonj! with ihe pencral public, were in vital tee on Minority Programs of the Association of rascism. They also explored values, communica- the Community College of Philadelphia. by Rnsc Hill Campus Ministries In show their College Unions-International (ACU-I) Region 3 tions and awareness which are essential ID According to Michael Sullivan, assistant support to those affected by the AIDS crisis by held a conference entitled "Leadership Respon- developing effective multicultural programs on dean of students for students activities, about 75 .ilii:iidini> an all-mpht prayer vigil last I rulav sibility and Multiculturalism" last Friday on the individual campuses. Presenters at the afternoon people attended the.conference on Friday. Includ- night beginning al 9 p rn in ihc UmviMsity second floor of McGinley Center. workshops included Hector Oritz, associate dean ed were Dr. .Fred D. Phelps, dean of students Church. The day was divided into two sessions, mor- from Lehman College-CUNY, and assistant In a siaiiMiioM to the pros-; issued last wi-ek. ning and afternoon. The morning session (9:00 "Ml of these workshops directors of Activities from many other institu- Rev Paul W. Bryant, S.J . director of campus a.m. -

A Rhetoric of Sports Talk Radio John D

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 11-28-2005 A Rhetoric of Sports Talk Radio John D. Reffue University of South Florida Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Reffue, John D., "A Rhetoric of Sports Talk Radio" (2005). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/832 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Rhetoric of Sports Talk Radio by John D. Reffue A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Communication College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Co-Major Professor: Eric M. Eisenberg, Ph.D. Co-Major Professor: Daniel S. Bagley III, Ph.D. Elizabeth Bell, Ph.D Gilbert B. Rodman, Ph.D. Date of Approval: November 28, 2005 Keywords: media studies, popular culture, performance studies, masculinity, community © Copyright 2006, John D. Reffue Acknowledgements I would like to begin by thanking my parents, David and Ann Reffue who supported and encouraged my love of communication from my very earliest years and who taught me that loving your work will bring a lifetime of rewards. Special thanks also to my brother and sister-in-law Doug and Eliana Reffue and my grandmother, Julia Tropia, for their love and encouragement throughout my studies and throughout my life. -

Ernie Davis Led the Way for the Orange Offense, Which Averaged 451 Yards Per Game

Syracuse football OUR MISSION IS TO WIN WITH HARDNOSED INTEGRITY WHILE QUIETLY SERVING OUR COMMUNITY! NEW YORK’S COLLEGE TEAM 2-0 in Yankee Stadium New Era Pinstripe Bowl 2010 2012 games for the Orange football program in 13 MetLife Stadium in the next 25 years. men’s lacrosse Big City Classic 3 titles at MetLife Stadium. The Orange played in the FIRST 1st sporting event held at MetLife Stadium. wins for the Orange men’s basketball team in 166 games 92 at Madison Square Garden. minutes played in Syracuse’s SIX overtime thriller against 226 Connecticut in 2009 at Madison Square Garden. The only BCS school in the Empire State, Syracuse University is New York’s College Team. Victories in the 2010 and 2012 New Era Pinstripe Bowls in Yankee Stadium and overwhelming success for the men’s basketball team in Madison Square Garden underscore Syracuse’s pprominencerominence iinn tthehe nnation’sation’s bbiggestiggest ccity,ity, wwhichhich iiss hhomeome ttoo SSyracuseyracuse UUniversity’sniversity’s llargestargest aalumnilumni bbase.ase. TThehe OOrangerange hhueue eextendsxtends iintonto NNewew JJerseyersey wwherehere MMetLifeetLife SStadiumtadium hhasas pplayedlayed hhostost ttoo 111-time1-time nnationalational cchampionhampion SSyracuseyracuse mmen’sen’s llacrosseacrosse ccontestsontests aandnd wwillill bbee hhomeome ttoo tthehe ffootballootball OOrangerange fforor mmultipleultiple ggamesames iinn thethe nnextext ttwowo ddecades,ecades, iincludingncluding tthehe 22013013 NNewew YYork’sork’s CCollegeollege CClassiclassic aagainstgainst PPennenn SStatetate oonn AAugustugust 331.1. TThehe OOrangerange bbrandrand iiss pprominentrominent oonn tthehe aairwavesirwaves aacrosscross NNewew YYorkork SStatetate vviaia tthehe SSyracuseyracuse IIMGMG NNetwork,etwork, iincludingncluding ggameame aandnd ccoachesoaches sshowhow bbroadcasts,roadcasts, aandnd iinn tthehe BBigig AApple,pple, wwithith ggamesames ttelevisedelevised oonn tthehe MMSGSG andand YYESES Networks.Networks. -

PDF Download Voices of Summer : Ranking Baseballs 101 All-Time

VOICES OF SUMMER : RANKING BASEBALLS 101 ALL- TIME BEST ANNOUNCERS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Curt Smith | 432 pages | 04 Apr 2005 | Carroll & Graf Publishers Inc | 9780786714469 | English | New York, United States Voices of Summer : Ranking Baseballs 101 All-time Best Announcers PDF Book Louis, so I had a basic idea of how to survive back behind the plate. We heard everything they said, even during commercials. And if one of those homers was a Mariners grand slam, well, Niehaus went crazy. Spending nearly two generations at the microphone for Yankees games, Phil Rizzuto saw some of the game's best players take the field while he worked as a broadcaster once his playing days were over. Scully has meant as much to Major League Baseball—and, specifically, Dodgers baseball—as all but a handful of people in the history of the game. He was hired by the Dodgers in and became a Brooklyn institution. Patterson, Ted. One day, a secretary informed him that a Mr. He was paired with Dizzy Dean on the network's broadcasts in the early s, though the two men often argued and never got along. Bob Prince His second wife was vaudeville performer Ramona ; they married on 14 June , and stayed together until her death in December Bert Wilson Sacramento , California , U. Beloved for his self-deprecating humor, he would be the first person to make fun of his rather unremarkable playing career, particularly his offensive statistics. I am in desperate need of a tissue here! About Help Legal. Bud Blattner was world table tenis champion at Full Name Robert George Uecker.