Why Do Curlews Numenius Have Decurved Bills?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The First Record of Far Eastern Curlew (Numenius Madagascariensis) in British Columbia

The First Record of Far Eastern Curlew (Numenius madagascariensis) in British Columbia. By Rick Toochin and Don Cecile. Submitted: April 15, 2018. Introduction and Distribution The Far Eastern Curlew (Numenius madagascariensis) is the largest migratory shorebird in the world. This species is found only along the East Asian–Australasian Flyway. The Far Eastern Curlew breeds on open mossy or transitional bogs, moss-lichen bogs and wet meadows, and on the swampy shores of small lakes in Siberia and Kamchatka in Russia, as well as in north-eastern Mongolia and China (Hayman et al. 1986, del Hoyo et al. 1996). The Yellow Sea of the Republic of Korea and China is a vitally important stopover site on migration. This species is also a common passage migrant in Japan and Indonesia, and is occasionally recorded moving through Thailand, Brunei, Bangladesh, Vietnam, Philippines, Malaysia and Singapore (O’Brien et al. 2006). During the winter a few birds occur in southern Republic of Korea, Japan, China, and Taiwan (Brazil 2009, EAAFP 2017). About 25% of the population is thought to winter in the Philippines, Indonesia and Papua New Guinea. Most birds, approximately 73% or 28,000 individuals, spend the winter in Australia, where birds are found primarily on the coast of all states, particularly the north, east and south-east regions including Tasmania (Bamford et al. 2008, BirdLife 2016). In the early 2000’s, the global population of the Far Eastern Curlew was estimated at 38,000 individuals (BirdLife 2016). Unfortunately due to the fact that the global population is declining, the true population size is likely to be much smaller, and may not exceed 20,000 individuals (BirdLife 2016). -

Keys to Identifying Little Curlew

MIGRATION PATTERN Keys to identifying Little Curlew Little Curlewin winterquarters at Cairns, Queensland,Australia, November 1975. Photo/Toma• Pain Gardner Not surprisingly,no ornithologisthas seen both the Little and Eskimo curlews nutus)is a speciesheld by some This new speciesFor North heauthorsLittleto Curlew be conspecific(Numenius with mi- in the field. The only detailedpublished the Eskimo Curlew (N. borealis). It America can be readily comparisonis that based by Farrand breeds in northeastern Siberia (Labutin identified in flight and (1977) on the skins of both. He conclud- and others, 1982) and winters in Austra- producesa variety of vocal ed thatthe two formsare separablein the lasia. This speciesis regardedas "rare, and instrumental sounds field under ideal conditions, and writes: little-studied and threatened," rather than "The Eskimo Curlew is a more boldly "endangered,"in the U.S.S.R. (Banni- and coarselymarked bird, with heavier kov, 1978). Brett A. Lane, the wader streakingon the sides of the face and studiescoordinator for the Royal Austra- neck, and dark chevrons on the breast and lasian Ornithologists' Union (pets. flanks;the Little Curlewhas a relatively comm., December1982), saysthe spe- Jeffery Boswail morefinely streakedface and neck, and cies "possiblynumbers many thousands the breast is streaked rather than marked (10,000+ ?)." and with chevrons,the chevronsbeing few in The Little Curlew was recently ob- number and confined to the flanks. In served for the first time in North Amer- Boris N. Veprintsev bothspecies the underwing covertsand ica. The species'closest breeding ground axillaries are barred with dark brown, but to North America is only about 1250 in the Eskimo Curlew these feathers are a mileswest of the nearestpoint of main- rich cinnamon, while in the Little Curlew land Alaska. -

Population Analysis and Community Workshop for Far Eastern Curlew Conservation Action in Pantai Cemara, Desa Sungai Cemara – Jambi

POPULATION ANALYSIS AND COMMUNITY WORKSHOP FOR FAR EASTERN CURLEW CONSERVATION ACTION IN PANTAI CEMARA, DESA SUNGAI CEMARA – JAMBI Final Report Small Grant Fund of the EAAFP Far Eastern Curlew Task Force Iwan Febrianto, Cipto Dwi Handono & Ragil S. Rihadini Jambi, Indonesia 2019 The aim of this project are to Identify the condition of Far Eastern Curlew Population and the remaining potential sites for Far Eastern Curlew stopover in Sumatera, Indonesia and protect the remaining stopover sites for Far Eastern Curlew by educating the government, local people and community around the sites as the effort of reducing the threat of habitat degradation, habitat loss and human disturbance at stopover area. INTRODUCTION The Far Eastern Curlew (Numenius madagascariencis) is the largest shorebird in the world and is endemic to East Asian – Australian Flyway. It is one of the Endangered migratory shorebird with estimated global population at 38.000 individual, although a more recent update now estimates the population at 32.000 (Wetland International, 2015 in BirdLife International, 2017). An analysis of monitoring data collected from around Australia and New Zealand (Studds et al. in prep. In BirdLife International, 2017) suggests that the species has declined much more rapidly than was previously thought; with an annual rate of decline of 0.058 equating to a loss of 81.7% over three generations. Habitat loss occuring as a result of development is the most significant threat currently affecting migratory shorebird along the EAAF (Melville et al. 2016 in EAAFP 2017). Loss of habitat at critical stopover sites in the Yellow Sea is suspected to be the key threat to this species and given that it is restricted to East Asian - Australasian Flyway, the declines in the non-breeding are to be representative of the global population. -

Draft Version Target Shorebird Species List

Draft Version Target Shorebird Species List The target species list (species to be surveyed) should not change over the course of the study, therefore determining the target species list is an important project design task. Because waterbirds, including shorebirds, can occur in very high numbers in a census area, it is often not possible to count all species without compromising the quality of the survey data. For the basic shorebird census program (protocol 1), we recommend counting all shorebirds (sub-Order Charadrii), all raptors (hawks, falcons, owls, etc.), Common Ravens, and American Crows. This list of species is available on our field data forms, which can be downloaded from this site, and as a drop-down list on our online data entry form. If a very rare species occurs on a shorebird area survey, the species will need to be submitted with good documentation as a narrative note with the survey data. Project goals that could preclude counting all species include surveys designed to search for color-marked birds or post- breeding season counts of age-classed bird to obtain age ratios for a species. When conducting a census, you should identify as many of the shorebirds as possible to species; sometimes, however, this is not possible. For example, dowitchers often cannot be separated under censuses conditions, and at a distance or under poor lighting, it may not be possible to distinguish some species such as small Calidris sandpipers. We have provided codes for species combinations that commonly are reported on censuses. Combined codes are still species-specific and you should use the code that provides as much information as possible about the potential species combination you designate. -

Growth and Development of Long-Billed Curlew Chicks

April 1973] General Notes 435 Pitelka and Donald L. Beaver critically read the manuscript. This work was con- ducted under the I.B.P. Analysis of Ecosystems-TundraProgram and supported by a grant to F. A. Pitelka from the National ScienceFoundation.--THo•rAs W. CUSTrR, Department o! Zoology and Museum o! Vertebrate Zoology, University o! California, Berkeley,California 94720. Accepted9 May 72. Growth and development of Long-billed Curlew chicks.--Compared with the altricial nestlings of passerinesand the semiprecocialyoung of gulls, few studies of the growth and developmentof the precocialchicks of the Charadrii have been made (Pettingill, 1970: 378). In Europe, yon Frisch (1958, 1959) describedthe develop- ment of behavior in 14 plovers and sandpipers. Davis (1943) and Nice (1962) have reported on the growth of Killdeer (Charadriusvociferus), Nice (1962) on the Spotted Sandpiper (Actiris macularia), and Webster (1942) on the growth and development of plumages in the Black Oystercatcher (Haematopus bachmani). Pettingill (1936) studiedthe atypical AmericanWoodcock (Philohelaminor). Among the curlews, Genus Numenius, only the Eurasian Curlew (N. arquata) has been studied (von Frisch, 1956). Becauseof the scant knowledgeabout the development of the youngin the Charadriiand the scarcityof informationon all aspectsof the breeding biology of the Long-billed Curlew (N. americanus) (Palmer, 1967), I believe that the following data on the growth and development of Long-billed Curlew chicks are relevant. I took four eggs,one being pipped, from a nest 10 miles west of Brigham City, Box Elder County, Utah, on 24 May 1966. One egg was preservedimmediately for additional study, the others I placed in a 4' X 3' X 2' cardboard box with a 60-watt lamp for warmth in a vacant room in my home until they hatched. -

List of Shorebird Profiles

List of Shorebird Profiles Pacific Central Atlantic Species Page Flyway Flyway Flyway American Oystercatcher (Haematopus palliatus) •513 American Avocet (Recurvirostra americana) •••499 Black-bellied Plover (Pluvialis squatarola) •488 Black-necked Stilt (Himantopus mexicanus) •••501 Black Oystercatcher (Haematopus bachmani)•490 Buff-breasted Sandpiper (Tryngites subruficollis) •511 Dowitcher (Limnodromus spp.)•••485 Dunlin (Calidris alpina)•••483 Hudsonian Godwit (Limosa haemestica)••475 Killdeer (Charadrius vociferus)•••492 Long-billed Curlew (Numenius americanus) ••503 Marbled Godwit (Limosa fedoa)••505 Pacific Golden-Plover (Pluvialis fulva) •497 Red Knot (Calidris canutus rufa)••473 Ruddy Turnstone (Arenaria interpres)•••479 Sanderling (Calidris alba)•••477 Snowy Plover (Charadrius alexandrinus)••494 Spotted Sandpiper (Actitis macularia)•••507 Upland Sandpiper (Bartramia longicauda)•509 Western Sandpiper (Calidris mauri) •••481 Wilson’s Phalarope (Phalaropus tricolor) ••515 All illustrations in these profiles are copyrighted © George C. West, and used with permission. To view his work go to http://www.birchwoodstudio.com. S H O R E B I R D S M 472 I Explore the World with Shorebirds! S A T R ER G S RO CHOOLS P Red Knot (Calidris canutus) Description The Red Knot is a chunky, medium sized shorebird that measures about 10 inches from bill to tail. When in its breeding plumage, the edges of its head and the underside of its neck and belly are orangish. The bird’s upper body is streaked a dark brown. It has a brownish gray tail and yellow green legs and feet. In the winter, the Red Knot carries a plain, grayish plumage that has very few distinctive features. Call Its call is a low, two-note whistle that sometimes includes a churring “knot” sound that is what inspired its name. -

Long-Billed Curlew ASSESSING HABITAT QUALITY for PRIORITY WILDLIFE SPECIES in COLORADO WETLANDS

COLORADO PARKS & WILDLIFE Long-billed Curlew ASSESSING HABITAT QUALITY FOR PRIORITY WILDLIFE SPECIES IN COLORADO WETLANDS Species Distribution Range Long-billed curlews breed in the western United States, including eastern Colorado, and in southwestern Canada. During migration, long-billed curlews occur sporadically in western Colorado and regularly throughout eastern Colorado. © “MIKE” MICHAEL L. BAIRD BAIRD L. MICHAEL “MIKE” © Long-billed curlews (Numenius americanus, Family Scolopacidae) have a distinctive long bill that curves downward. They are can be found near playas and ponds in eastern Colorado. insects, particularly grasshoppers. Species Description They also eat some vertebrate species, Identification including fish, amphibians, and bird The long-billed curlew, at 20–26 inches eggs/nestlings. Breeding in length, is the largest shorebird in Winter North America. Their primitive- Conservation Status sounding curlee vocalizations are Populations of long-billed curlews considered a harbinger of spring. Their have experienced overall declines in down-curved, sickle-shaped bill is the many areas, especially throughout the largest among shorebirds and inspired eastern United States, due primarily to their genus name, Numenius, derived habitat loss and historic over-hunting. from the Greek word, noumenios, In Colorado, long-billed curlews are meaning of the new crescent moon. listed as a Tier 2 Species of Great- est Conservation Need (CPW 2015). Preferred Habitats The Breeding Bird Survey indicates a Long-billed curlews are considered a significant population decline in Colo- grassland species, but they are rarely rado, and the Colorado Breeding Bird observed far from water. In Colorado, Atlas indicates a decrease in distribu- they are usually associated with ponds, tion. -

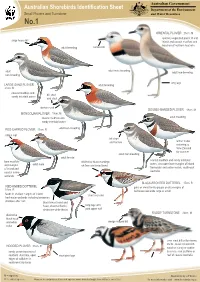

Australian Shorebirds Identification Sheet Department of the Environment Small Plovers and Turnstone and Water Resources No.1

Australian Government Australian Shorebirds Identification Sheet Department of the Environment Small Plovers and Turnstone and Water Resources No.1 ORIENTAL PLOVER 25cm. M sparsely vegetated plains of arid large heavy bill inland and coastal mudflats and beaches of northern Australia adult breeding narrow bill adult male breeding adult adult non-breeding non-breeding long legs LARGE SAND PLOVER adult breeding 21cm. M coastal mudflats and bill short sandy intertidal zones and stout darker mask DOUBLE-BANDED PLOVER 19cm. M MONGOLIAN PLOVER 19cm. M coastal mudflats and adult breeding sandy intertidal zones RED-CAPPED PLOVER 15cm. R adult non-breeding rufous cap bill short and narrow winter visitor returning to New Zealand for summer adult non-breeding adult female coastal mudflats and sandy intertidal bare mudflats distinctive black markings zones, also open bare margins of inland and margins adult male on face and breastband of inland and freshwater and saline marsh, south-east coastal saline Australia wetlands BLACK-FRONTED DOTTEREL 17cm. R RED-KNEED DOTTEREL pairs or small family groups on dry margins of 18cm. R feshwater wetlands large or small feeds in shallow margins of inland short rear end freshwater wetlands including temporary shallows after rain black breast band and head, chestnut flanks, long legs with distinctive white throat pink upper half RUDDY TURNSTONE 23cm. M distinctive black hood and white wedge shaped bill collar uses stout bill to flip stones, shells, seaweed and drift- 21cm. R HOODED PLOVER wood on sandy or cobble sandy ocean beaches of beaches, rock platform or southern Australia, open short pink legs reef of coastal Australia edges of saltlakes in south-west Australia M = migratory . -

First Record of Long-Billed Curlew Numenius Americanus in Peru and Other Observations of Nearctic Waders at the Virilla Estuary Nathan R

Cotinga 26 First record of Long-billed Curlew Numenius americanus in Peru and other observations of Nearctic waders at the Virilla estuary Nathan R. Senner Received 6 February 2006; final revision accepted 21 March 2006 Cotinga 26(2006): 39–42 Hay poca información sobre las rutas de migración y el uso de los sitios de la costa peruana por chorlos nearcticos. En el fin de agosto 2004 yo reconocí el estuario de Virilla en el dpto. Piura en el noroeste de Peru para identificar los sitios de descanso para los Limosa haemastica en su ruta de migración al sur y aprender más sobre la migración de chorlos nearcticos en Peru. En Virilla yo observí más de 2.000 individuales de 23 especios de chorlos nearcticos y el primer registro de Numenius americanus de Peru, la concentración más grande de Limosa fedoa en Peru, y una concentración excepcional de Limosa haemastica. La combinación de esas observaciones y los resultados de un estudio anterior en el invierno boreal sugiere la posibilidad que Virilla sea muy importante para chorlos nearcticos en Peru. Las observaciones, también, demuestren la necesidad hacer más estudios en la costa peruana durante el año entero, no solemente durante el punto máximo de la migración de chorlos entre septiembre y noviembre. Shorebirds are poorly known in Peru away from bordered for a few hundred metres by sand and established study sites such as Paracas reserve, gravel before low bluffs rise c.30 m. Very little dpto. Ica, and those close to metropolitan areas vegetation grows here, although cows, goats and frequented by visiting birdwatchers and tour pigs owned by Parachique residents graze the area. -

Black-Tailed Godwits in West African Winter Staging Areas

Alterra is part of the international expertise organisation Wageningen UR (University & Research centre). Our mission is ‘To explore the potential of nature to improve the quality of life’. Within Wageningen UR, nine research institutes – both specialised and applied – have joined forces with Wageningen University and Van Hall Larenstein University of Black-tailed Godwits in West African winter Applied Sciences to help answer the most important questions in the domain of healthy food and living environment. With approximately 40 locations (in the Netherlands, Brazil and China), 6,500 members of staff and 10,000 students, Wageningen UR is one of the leading organisations in its domain worldwide. The integral approach to problems and the cooperation between the exact sciences and the technological and social disciplines are at the heart of the staging areas Wageningen Approach. Alterra is the research institute for our green living environment. We offer a combination of practical and scientific Habitat use and hunting-related mortality research in a multitude of disciplines related to the green world around us and the sustainable use of our living environment, such as flora and fauna, soil, water, the environment, geo-information and remote sensing, landscape and spatial planning, man and society. Alterra Report 2058 ISSN 1566-7197 More information: www.alterra.wur.nl/uk David Kleijn, Jan van der Kamp, Hamilton Monteiro, Idrissa Ndiaye, Eddy Wymenga and Leo Zwarts Black-tailed Godwits in West African winter staging areas Commissioned by the Dutch Ministry of Agriculture, Nature Conservation and Food safety, Direction Nature Conservation. Carried out in the framework of project BO-10-003-002. -

SIS) – 2017 Version

Information Sheet on EAA Flyway Network Sites Information Sheet on EAA Flyway Network Sites (SIS) – 2017 version Available for download from http://www.eaaflyway.net/about/the-flyway/flyway-site-network/ Categories approved by Second Meeting of the Partners of the East Asian-Australasian Flyway Partnership in Beijing, China 13-14 November 2007 - Report (Minutes) Agenda Item 3.13 Notes for compilers: 1. The management body intending to nominate a site for inclusion in the East Asian - Australasian Flyway Site Network is requested to complete a Site Information Sheet. The Site Information Sheet will provide the basic information of the site and detail how the site meets the criteria for inclusion in the Flyway Site Network. When there is a new nomination or an SIS update, the following sections with an asterisk (*), from Questions 1-14 and Question 30, must be filled or updated at least so that it can justify the international importance of the habitat for migratory waterbirds. 2. The Site Information Sheet is based on the Ramsar Information Sheet. If the site proposed for the Flyway Site Network is an existing Ramsar site then the documentation process can be simplified. 3. Once completed, the Site Information Sheet (and accompanying map(s)) should be submitted to the Flyway Partnership Secretariat. Compilers should provide an electronic (MS Word) copy of the Information Sheet and, where possible, digital versions (e.g. shapefile) of all maps. ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- -

Migratory Shorebird Guild

Migratory Shorebird Guild Piping Plover Charadrius melodus Sanderling Calidris alba Semipalmated Plover Charadrius semipalmatus Red Knot Calidris canutus Black-bellied Plover Pluvialis squatarola Marbled Godwit Limosa fedoa American Golden Plover Pluvialis dominica Buff-breasted Sandpiper Tryngites subruficollis Wimbrel Numenius phaeopus White-rumped Sandpiper Calidris fuscicollis Long-billed Curlew Numenius americanus Pectoral Sandpiper Calidris melanotos Greater Yellowlegs Tringa melanoleuca Purple Sandpiper Calidris maritima Lesser Yellowlegs Tringa flavipes Stilt Sandpiper Calidris himantopus Solitary Sandpiper Tringa solitaria Wilson’s Snipe Gallinago gallinago delicata Spotted Sandpiper Actitis macularia American Avocet Recurvirostra Americana Upland Sandpiper Bartramia longicauda Least Sandpiper Calidris minutilla Semipalmated Sandpiper Calidris pusilla Short-billed Dowitcher Limnodromus griseus Western Sandpiper Calidris mauri Long-billed Dowitcher Limnodromus scolopaceus Dunlin Calidris alpina Contributors: Felicia Sanders and Thomas M. Murphy DESCRIPTION Photograph by SC DNR Taxonomy and Basic Description The migratory shorebird guild is composed of birds in the Charadrii suborder. Migrants in South Carolina represent three families: Scolopacidae (sandpipers), Charadriidae (plovers) and Recurvirostridae (avocets). Sandpipers are the most diverse family of shorebirds. Their tactile foraging strategy encompasses probing in soft mud or sand for invertebrates. Plovers are medium size birds, with relatively short, thick bills and employ a distinctive foraging strategy. They stand, looking for prey and then run to feed on detected invertebrates. Avocets are large shorebirds with long recurved bills and partial webbing between the toes. They feed employing both tactile and visual methods. Shorebirds are characterized by long legs for wading and wings designed for quick flight and transcontinental migrations. Migrations can span continents; for example, red knots migrate from the Canadian arctic to the southern tip of South America.