Where Have All the Curlews Gone?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Keys to Identifying Little Curlew

MIGRATION PATTERN Keys to identifying Little Curlew Little Curlewin winterquarters at Cairns, Queensland,Australia, November 1975. Photo/Toma• Pain Gardner Not surprisingly,no ornithologisthas seen both the Little and Eskimo curlews nutus)is a speciesheld by some This new speciesFor North heauthorsLittleto Curlew be conspecific(Numenius with mi- in the field. The only detailedpublished the Eskimo Curlew (N. borealis). It America can be readily comparisonis that based by Farrand breeds in northeastern Siberia (Labutin identified in flight and (1977) on the skins of both. He conclud- and others, 1982) and winters in Austra- producesa variety of vocal ed thatthe two formsare separablein the lasia. This speciesis regardedas "rare, and instrumental sounds field under ideal conditions, and writes: little-studied and threatened," rather than "The Eskimo Curlew is a more boldly "endangered,"in the U.S.S.R. (Banni- and coarselymarked bird, with heavier kov, 1978). Brett A. Lane, the wader streakingon the sides of the face and studiescoordinator for the Royal Austra- neck, and dark chevrons on the breast and lasian Ornithologists' Union (pets. flanks;the Little Curlewhas a relatively comm., December1982), saysthe spe- Jeffery Boswail morefinely streakedface and neck, and cies "possiblynumbers many thousands the breast is streaked rather than marked (10,000+ ?)." and with chevrons,the chevronsbeing few in The Little Curlew was recently ob- number and confined to the flanks. In served for the first time in North Amer- Boris N. Veprintsev bothspecies the underwing covertsand ica. The species'closest breeding ground axillaries are barred with dark brown, but to North America is only about 1250 in the Eskimo Curlew these feathers are a mileswest of the nearestpoint of main- rich cinnamon, while in the Little Curlew land Alaska. -

Australian Shorebirds Identification Sheet Department of the Environment Small Plovers and Turnstone and Water Resources No.1

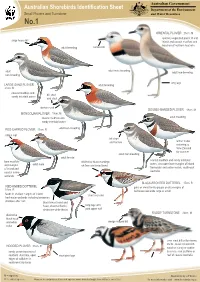

Australian Government Australian Shorebirds Identification Sheet Department of the Environment Small Plovers and Turnstone and Water Resources No.1 ORIENTAL PLOVER 25cm. M sparsely vegetated plains of arid large heavy bill inland and coastal mudflats and beaches of northern Australia adult breeding narrow bill adult male breeding adult adult non-breeding non-breeding long legs LARGE SAND PLOVER adult breeding 21cm. M coastal mudflats and bill short sandy intertidal zones and stout darker mask DOUBLE-BANDED PLOVER 19cm. M MONGOLIAN PLOVER 19cm. M coastal mudflats and adult breeding sandy intertidal zones RED-CAPPED PLOVER 15cm. R adult non-breeding rufous cap bill short and narrow winter visitor returning to New Zealand for summer adult non-breeding adult female coastal mudflats and sandy intertidal bare mudflats distinctive black markings zones, also open bare margins of inland and margins adult male on face and breastband of inland and freshwater and saline marsh, south-east coastal saline Australia wetlands BLACK-FRONTED DOTTEREL 17cm. R RED-KNEED DOTTEREL pairs or small family groups on dry margins of 18cm. R feshwater wetlands large or small feeds in shallow margins of inland short rear end freshwater wetlands including temporary shallows after rain black breast band and head, chestnut flanks, long legs with distinctive white throat pink upper half RUDDY TURNSTONE 23cm. M distinctive black hood and white wedge shaped bill collar uses stout bill to flip stones, shells, seaweed and drift- 21cm. R HOODED PLOVER wood on sandy or cobble sandy ocean beaches of beaches, rock platform or southern Australia, open short pink legs reef of coastal Australia edges of saltlakes in south-west Australia M = migratory . -

SIS) – 2017 Version

Information Sheet on EAA Flyway Network Sites Information Sheet on EAA Flyway Network Sites (SIS) – 2017 version Available for download from http://www.eaaflyway.net/about/the-flyway/flyway-site-network/ Categories approved by Second Meeting of the Partners of the East Asian-Australasian Flyway Partnership in Beijing, China 13-14 November 2007 - Report (Minutes) Agenda Item 3.13 Notes for compilers: 1. The management body intending to nominate a site for inclusion in the East Asian - Australasian Flyway Site Network is requested to complete a Site Information Sheet. The Site Information Sheet will provide the basic information of the site and detail how the site meets the criteria for inclusion in the Flyway Site Network. When there is a new nomination or an SIS update, the following sections with an asterisk (*), from Questions 1-14 and Question 30, must be filled or updated at least so that it can justify the international importance of the habitat for migratory waterbirds. 2. The Site Information Sheet is based on the Ramsar Information Sheet. If the site proposed for the Flyway Site Network is an existing Ramsar site then the documentation process can be simplified. 3. Once completed, the Site Information Sheet (and accompanying map(s)) should be submitted to the Flyway Partnership Secretariat. Compilers should provide an electronic (MS Word) copy of the Information Sheet and, where possible, digital versions (e.g. shapefile) of all maps. ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- -

Pilbara Shorebirds and Seabirds

Shorebirds and seabirds OF THE PILBARA COAST AND ISLANDS Montebello Islands Pilbara Region Dampier Barrow Sholl Island Karratha Island PERTH Thevenard Island Serrurier Island South Muiron Island COASTAL HIGHWAY Onslow Pannawonica NORTH WEST Exmouth Cover: Greater sand plover. This page: Great knot. Photos – Grant Griffin/DBCA Photos – Grant page: Great knot. This Greater sand plover. Cover: Shorebirds and seabirds of the Pilbara coast and islands The Pilbara coast and islands, including the Exmouth Gulf, provide important refuge for a number of shorebird and seabird species. For migratory shorebirds, sandy spits, sandbars, rocky shores, sandy beaches, salt marshes, intertidal flats and mangroves are important feeding and resting habitat during spring and summer, when the birds escape the harsh winter of their northern hemisphere breeding grounds. Seabirds, including terns and shearwaters, use the islands for nesting. For resident shorebirds, including oystercatchers and beach stone-curlews, the islands provide all the food, shelter and undisturbed nesting areas they need. What is a shorebird? Shorebirds, also known as ‘waders’, are a diverse group of birds mostly associated with wetland and coastal habitats where they wade in shallow water and feed along the shore. This group includes plovers, sandpipers, stints, curlews, knots, godwits and oystercatchers. Some shorebirds spend their entire lives in Australia (resident), while others travel long distances between their feeding and breeding grounds each year (migratory). TYPES OF SHOREBIRDS Roseate terns. Photo – Grant Griffin/DBCA Photo – Grant Roseate terns. Eastern curlew Whimbrel Godwit Plover Turnstone Sandpiper Sanderling Diagram – adapted with permission from Ted A Morris Jr. Above: LONG-DISTANCE TRAVELLERS To never experience the cold of winter sounds like a good life, however migratory shorebirds put a lot of effort in achieving their endless summer. -

Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (And 113 Non-Species Taxa) in Accordance with the 62Nd AOU Supplement (2021), Sorted Taxonomically

Four-letter (English Name) and Six-letter (Scientific Name) Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (and 113 Non-Species Taxa) in accordance with the 62nd AOU Supplement (2021), sorted taxonomically Prepared by Peter Pyle and David F. DeSante The Institute for Bird Populations www.birdpop.org ENGLISH NAME 4-LETTER CODE SCIENTIFIC NAME 6-LETTER CODE Highland Tinamou HITI Nothocercus bonapartei NOTBON Great Tinamou GRTI Tinamus major TINMAJ Little Tinamou LITI Crypturellus soui CRYSOU Thicket Tinamou THTI Crypturellus cinnamomeus CRYCIN Slaty-breasted Tinamou SBTI Crypturellus boucardi CRYBOU Choco Tinamou CHTI Crypturellus kerriae CRYKER White-faced Whistling-Duck WFWD Dendrocygna viduata DENVID Black-bellied Whistling-Duck BBWD Dendrocygna autumnalis DENAUT West Indian Whistling-Duck WIWD Dendrocygna arborea DENARB Fulvous Whistling-Duck FUWD Dendrocygna bicolor DENBIC Emperor Goose EMGO Anser canagicus ANSCAN Snow Goose SNGO Anser caerulescens ANSCAE + Lesser Snow Goose White-morph LSGW Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Intermediate-morph LSGI Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Blue-morph LSGB Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Greater Snow Goose White-morph GSGW Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Intermediate-morph GSGI Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Blue-morph GSGB Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Snow X Ross's Goose Hybrid SRGH Anser caerulescens x rossii ANSCAR + Snow/Ross's Goose SRGO Anser caerulescens/rossii ANSCRO Ross's Goose -

Eskimo Curlew (Numenius Borealis) 5-Year Review

Eskimo Curlew (Numenius borealis) 5-Year Review: Summary and Evaluation U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Fairbanks Fish and Wildlife Field Office Fairbanks, Alaska August 31, 2011 I. GENERAL INFORMATION The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service) is required by section 4(c)(2) of the Endangered Species Act of 1973 (ESA) to conduct a status review of each listed species at least once every 5 years. The purpose of a 5-year review is to evaluate whether or not the species’ status has changed since it was listed (or since the most recent 5-year review). Based on the 5-year review, we recommend whether the species should be removed from the list of endangered and threatened species, changed in status from endangered to threatened, or changed in status from threatened to endangered. Our original listing of a species as endangered or threatened is based on the existence of threats attributable to one or more of the five threat factors described in section 4(a)(1) of the Act, and we must consider these same five factors in subsequent consideration of reclassification or delisting of a species. In the 5-year review, we consider the best available scientific and commercial data on the species, and focus on new information made available since the species was listed or last reviewed. If we recommend a change in listing status based on the results of the 5-year review, we must propose to do so through a separate rule-making process defined in the Act that includes public review and comment. -

Eskimo Curlew (Numenius Borealis)

COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the Eskimo Curlew Numenius borealis in Canada ENDANGERED 2009 COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: COSEWIC. 2009. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Eskimo Curlew Numenius borealis in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vii + 32 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm). Previous report(s): COSEWIC. 2000. COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the Eskimo Curlew Numenius borealis in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vii + 17 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm) Gratto-Trevor, C. 2000. Update COSEWIC status report on the Eskimo Curlew Numenius borealis in Canada, in COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the Eskimo Curlew Numenius borealis in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 1- 17 pp. Gollop, J.B., and C.E.P. Shier. 1978. COSEWIC status report on the Eskimo Curlew Numenius borealis in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 32 pp. Production note: COSEWIC would like to acknowledge David A. Kirk and Jennie L. Pearce for writing the status report on the Eskimo Curlew Numenius borealis in Canada, prepared under contract with Environment Canada, overseen and edited by Jon McCracken, Co-chair, COSEWIC Birds Species Specialist Subcommittee. For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: 819-953-3215 Fax: 819-994-3684 E-mail: COSEWIC/[email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Également disponible en français sous le titre Ếvaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur le Courlis esquimau (Numenius borealis) au Canada. -

A Little-Known Species Reaches North America

DISTRIBUTION A little-known species reaches North America Ageelas a juvenile.this Little Curlew went abnost a monthin theSanta Maria Valle•:Note the di.vtribution qf pinl• Oll the lower tnandlble Photo:Septenlber 18. 1984/AlanS. Hopkins At home on the tundra steppesoF eastern Paul Lehman and Jon L. Dunn Siberia,the Little Curlew (Numeniusminutus) t has been recorded in southern CaliFornia nicaL Solitary Sandpiper(Tringa soli- who remainedat the originalsite, hearda northcrnSanta Barbara County, tarre), Baird's Sandpiper(C. bairdii), somewhatplover-like "too-whit" call and T California,HFSANTA isMARIA well-knownVALLI:Y for the in and Pectoral Sandpipcr (C. melanotos), briefly noteda shorebirdof medium size largcnumbcrs and varietics of shorebirds are annuallysccn in fall. with unmarkcd•brownish upperparts fly foundthere. Sincc regular censusing be- On September16. 1984. Louis Bcvicr by to hisside and disappear into the pas- gan in 1978, the lush pastureland,sct- and Kelly Steelefound ajuvenilc Curlcw ture. Given the overall size of the bird, tling ponds, and Santa Maria River Sandpiper(C. Jkrruginea), in a partially thecall, andthe brief viewsof the upper- mouthhavc producednumerous raritics, Iloodcdpasture, several miles westof the parts,hc assumedit was a LesserGolden- includingsevcral rccords each of Sharp- city of SantaMaria. Having beennotified Plover, but was bothered that the bird tailed Sandpiper(CalMris acuminata), of this sighting,several other birders, in- wasnot goldenenough above and that its andRuff (PhilomachuspugtlaX). as well cludingLehman, Brad Schram,and Tom silhouetteshowed too much body for- assmall numbers of SemipalmatedSand- Wurster, arrived at the site within two ward of the wings. pipers(C. pusilia), each fall. A flock of hours but could not relocate the bird that "Pacific"Lesser Golden-Plovers (Pluvia- day. -

Eighty-Mile Beach, Western Australia

Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands (RIS) Categories approved by Recommendation 4.7 (1990), as amended by Resolution VIII.13 of the 8th Conference of the Contracting Parties (2002) and Resolutions IX.1 Annex B, IX.6, IX.21 and IX. 22 of the 9th Conference of the Contracting Parties (2005). This Ramsar Information Sheet has been converted to meet the 2009 – 2012 format, but the RIS content has not been updated in this conversion. The new format seeks some additional information which could not yet be included. This information will be added when future updates of this Ramsar Information Sheet are completed. Until then, notes on any changes in the ecological character of the Ramsar site may be obtained from the Ecological Character Description (if completed) and other relevant sources. 1. Name and address of the compiler of this form: FOR OFFICE USE ONLY. Compiled by the Department of Conservation and Land DD MM YY Management (DCLM). All inquiries should be directed to: Jim Lane Designation date Site Reference Number DCLM 14 Queen Street Busselton WA 6280 Australia Tel: +61-8-9752-1677 Fax: +61-8-9752-1432 email: [email protected]. 2. Date this sheet was completed/updated: November 2003 3. Country: Australia 4. Name of the Ramsar site: The precise name of the designated site in one of the three official languages (English, French or Spanish) of the Convention. Alternative names, including in local language(s), should be given in parentheses after the precise name. Eighty-mile Beach, Western Australia 5. Designation of new Ramsar site or update of existing site: Eighty-mile Beach, Western Australia was designated on 7 June 1990. -

Population Trends, Threats, and Conservation Recommendations for Waterbirds in China Xiaodan Wang, Fenliang Kuang, Kun Tan and Zhijun Ma*

Wang et al. Avian Res (2018) 9:14 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40657-018-0106-9 Avian Research REVIEW Open Access Population trends, threats, and conservation recommendations for waterbirds in China Xiaodan Wang, Fenliang Kuang, Kun Tan and Zhijun Ma* Abstract Background: China is one of the countries with abundant waterbird diversity. Over the past decades, China’s water- birds have sufered increasing threats from direct and indirect human activities. It is important to clarify the popula- tion trends of and threats to waterbirds as well as to put forward conservation recommendations. Methods: We collected data of population trends of a total of 260 waterbird species in China from Wetlands Inter- national database. We calculated the number of species with increasing, declining, stable, and unknown trends. We collected threatened levels of waterbirds from the Red List of China’s Vertebrates (2016), which was compiled according to the IUCN criteria of threatened species. Based on literature review, we refned the major threats to the threatened waterbird species in China. Results: Of the total 260 waterbird species in China, 84 species (32.3%) exhibited declining, 35 species (13.5%) kept stable, and 16 species (6.2%) showed increasing trends. Population trends were unknown for 125 species (48.1%). There was no signifcant diference in population trends between the migratory (32.4% decline) and resident (31.8% decline) species or among waterbirds distributed exclusively along coasts (28.6% decline), inland (36.6% decline), and both coasts and inland (32.5% decline). A total of 38 species (15.1% of the total) were listed as threatened species and 27 species (10.8% of the total) Near Threatened species. -

Status and Occurrence of Little Curlew (Numenius Minutus) in British Columbia

Status and Occurrence of Little Curlew (Numenius minutus) in British Columbia. By Rick Toochin and Peter Hamel. Submitted: April 15, 2018. Introduction and Distribution The Little Curlew (Numenius minutus) is a small shorebird that is found breeding in isolated subalpine areas with stunted forests exclusively in Siberia from Yenisei River and western Chukotka region (Brazil 2009). This species is highly migratory stopping on open fields and short grassland habitat during migration and the winter (O’Brien et al. 2006, Brazil 2009). During the fall migration the Little Curlew migrates overland as a fairly common migrant throughout Eastern China, and is a rare to scarce migrant through Korea, Japan, and Taiwan (Brazil 2009). When leaving eastern China in the fall, the Little Curlew flies non-stop over water to in the fall to winter in Australia, where this species will gather in groups of up to several thousand birds (O’Brien et al. 2006). This species has been recorded somewhat regularly in New Guinea, and as a straggler in the Celebes, Borneo and the Philippines (Vaurie 1965), as well as in Tasmania and New Zealand (Labutin 1982, Cramp 1983, O’Brien et al. 2006, Brazil 2009). In North America, the Little Curlew is an accidental migrant vagrant along the entire West Coast from Alaska to California. There is a single record for Alaska of a bird found at St. Lawrence Island June 7-8, 1989 (Gibson and Kessel 1992). There is a single accepted sight record by the Washington Bird Records Committee for Washington State that was found at Leadbetter Point on May 6, 2001 (Mlodinow 2002, Wahl et al. -

Little Whimbrel: New to Britain and Ireland

Little Whimbrel: new to Britain and Ireland S.J. Moon ker Farm, near Sker Point, Mid Glamorgan, lies on the southern edge of Sextensive sandhills and slacks comprising Kenfig Pool and Dunes Local Nature Reserve. David E. J. Dicks and I were walking along a track adjacent to Sker Farm at about 15.45 GMT on 30th August 1982, when we disturbed two birds from nearby dunes. DEJD said 'Whimbrel' and both of us glanced at them through binoculars. One was indeed a Whimbrel Numeniusphaeopus, showing extensive white on its lower back and rump, but, to my surprise, I could see that the accompanying bird had completely brown upperparts. The Whimbrel flew away, but the second bird settled nervously about a hundred metres from us and, after a while, began feeding: a delicate picking of items, including small worms, from the dune-turf. My impressions through binoculars at this range were of a long-legged, elongated, small-headed, brown wader reminiscent of an Upland Sandpiper Bartramia longicauda. Excited, I set up my telescope and was amazed to see that the bird resembled a Whimbrel: it had a down-curve to its bill and possessed a crown-stripe and a supercilium. We were able to approach to within 50 m, but, since the bird was now on its own, it was difficult to make an accurate assessment of size, although I had previously thought that it was distinctly smaller than the accompanying Whimbrel. DEJD carefully stalked the bird and took several photographs, while I made the following brief field- description: Very like Whimbrel without white rump, but flanks, strongest towards rear.