Eskimo Curlew (Numenius Borealis) 5-Year Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Keys to Identifying Little Curlew

MIGRATION PATTERN Keys to identifying Little Curlew Little Curlewin winterquarters at Cairns, Queensland,Australia, November 1975. Photo/Toma• Pain Gardner Not surprisingly,no ornithologisthas seen both the Little and Eskimo curlews nutus)is a speciesheld by some This new speciesFor North heauthorsLittleto Curlew be conspecific(Numenius with mi- in the field. The only detailedpublished the Eskimo Curlew (N. borealis). It America can be readily comparisonis that based by Farrand breeds in northeastern Siberia (Labutin identified in flight and (1977) on the skins of both. He conclud- and others, 1982) and winters in Austra- producesa variety of vocal ed thatthe two formsare separablein the lasia. This speciesis regardedas "rare, and instrumental sounds field under ideal conditions, and writes: little-studied and threatened," rather than "The Eskimo Curlew is a more boldly "endangered,"in the U.S.S.R. (Banni- and coarselymarked bird, with heavier kov, 1978). Brett A. Lane, the wader streakingon the sides of the face and studiescoordinator for the Royal Austra- neck, and dark chevrons on the breast and lasian Ornithologists' Union (pets. flanks;the Little Curlewhas a relatively comm., December1982), saysthe spe- Jeffery Boswail morefinely streakedface and neck, and cies "possiblynumbers many thousands the breast is streaked rather than marked (10,000+ ?)." and with chevrons,the chevronsbeing few in The Little Curlew was recently ob- number and confined to the flanks. In served for the first time in North Amer- Boris N. Veprintsev bothspecies the underwing covertsand ica. The species'closest breeding ground axillaries are barred with dark brown, but to North America is only about 1250 in the Eskimo Curlew these feathers are a mileswest of the nearestpoint of main- rich cinnamon, while in the Little Curlew land Alaska. -

Australian Shorebirds Identification Sheet Department of the Environment Small Plovers and Turnstone and Water Resources No.1

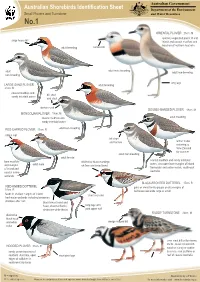

Australian Government Australian Shorebirds Identification Sheet Department of the Environment Small Plovers and Turnstone and Water Resources No.1 ORIENTAL PLOVER 25cm. M sparsely vegetated plains of arid large heavy bill inland and coastal mudflats and beaches of northern Australia adult breeding narrow bill adult male breeding adult adult non-breeding non-breeding long legs LARGE SAND PLOVER adult breeding 21cm. M coastal mudflats and bill short sandy intertidal zones and stout darker mask DOUBLE-BANDED PLOVER 19cm. M MONGOLIAN PLOVER 19cm. M coastal mudflats and adult breeding sandy intertidal zones RED-CAPPED PLOVER 15cm. R adult non-breeding rufous cap bill short and narrow winter visitor returning to New Zealand for summer adult non-breeding adult female coastal mudflats and sandy intertidal bare mudflats distinctive black markings zones, also open bare margins of inland and margins adult male on face and breastband of inland and freshwater and saline marsh, south-east coastal saline Australia wetlands BLACK-FRONTED DOTTEREL 17cm. R RED-KNEED DOTTEREL pairs or small family groups on dry margins of 18cm. R feshwater wetlands large or small feeds in shallow margins of inland short rear end freshwater wetlands including temporary shallows after rain black breast band and head, chestnut flanks, long legs with distinctive white throat pink upper half RUDDY TURNSTONE 23cm. M distinctive black hood and white wedge shaped bill collar uses stout bill to flip stones, shells, seaweed and drift- 21cm. R HOODED PLOVER wood on sandy or cobble sandy ocean beaches of beaches, rock platform or southern Australia, open short pink legs reef of coastal Australia edges of saltlakes in south-west Australia M = migratory . -

TESTING a MODEL THAT PREDICTS FUTURE BIRD LIST TOTALS by Robert W. Ricci Introduction One of the More Enjoyable Features of Bird

TESTING A MODEL THAT PREDICTS FUTURE BIRD LIST TOTALS by Robert W. Ricci Introduction One of the more enjoyable features of birding as a hobby is in keeping bird lists. Certainly getting into the habit of carefully recording our own personal birding experiences paves the way to a better understanding of the birds around us and prepares our minds for that chance encounter with a vagrant. In addition to our own field experiences, we advance our understanding of bird life through our reading and fraternization with other birders. One of the most useful ways we can communicate is by sharing our bird lists in Christmas Bird Counts (CBC), breeding bird surveys, and in the monthly compilation of field records as found, for example, in this journal. As important as our personal observation might be, however, it is only in the analysis of the cumulative experiences of many birders that trends emerge that can provide the substance to answer important questions such as the causes of vagrancy in birds (Veit 1989), changes in bird populations (Davis 1991), and bird migration patterns (Roberts 1995). Most birders, at one time or another, have speculated about what new avian milestones they will overtake in the future. For example, an article in this journal (Forster 1990) recorded the predictions of several birding gurus on which birds might be likely candidates as the next vagrants to add to the Massachusetts Avian Records Committee roster of 451 birds. Just as important as predictions of which birds might appear during your field activities are predictions of the total number of birds that you might expect to encounter. -

The Potential Breeding Range of Slender-Billed Curlew Numenius Tenuirostris Identified from Stable-Isotope Analysis

Bird Conservation International (2016) 0 : 1 – 10 . © BirdLife International, 2016 doi:10.1017/S0959270916000551 The potential breeding range of Slender-billed Curlew Numenius tenuirostris identified from stable-isotope analysis GRAEME M. BUCHANAN , ALEXANDER L. BOND , NICOLA J. CROCKFORD , JOHANNES KAMP , JAMES W. PEARCE-HIGGINS and GEOFF M. HILTON Summary The breeding areas of the Critically Endangered Slender-billed Curlew Numenius tenuirostris are all but unknown, with the only well-substantiated breeding records being from the Omsk prov- ince, western Siberia. The identification of any remaining breeding population is of the highest priority for the conservation of any remnant population. If it is extinct, the reliable identification of former breeding sites may help determine the causes of the species’ decline, in order to learn wider conservation lessons. We used stable isotope values in feather samples from juvenile Slender-billed Curlews to identify potential breeding areas. Modelled precipitation δ 2 H data were compared to feather samples of surrogate species from within the potential breeding range, to produce a calibration equation. Application of this calibration to samples from 35 Slender-billed Curlew museum skins suggested they could have originated from the steppes of northern Kazakhstan and part of southern Russia between 48°N and 56°N. The core of this area was around 50°N, some way to the south of the confirmed nesting sites in the forest steppes. Surveys for the species might be better targeted at the Kazakh steppes, rather than around the historically recog- nised nest sites of southern Russia which might have been atypical for the species. We consider whether agricultural expansion in this area may have contributed to declines of the Slender-billed Curlew population. -

SIS) – 2017 Version

Information Sheet on EAA Flyway Network Sites Information Sheet on EAA Flyway Network Sites (SIS) – 2017 version Available for download from http://www.eaaflyway.net/about/the-flyway/flyway-site-network/ Categories approved by Second Meeting of the Partners of the East Asian-Australasian Flyway Partnership in Beijing, China 13-14 November 2007 - Report (Minutes) Agenda Item 3.13 Notes for compilers: 1. The management body intending to nominate a site for inclusion in the East Asian - Australasian Flyway Site Network is requested to complete a Site Information Sheet. The Site Information Sheet will provide the basic information of the site and detail how the site meets the criteria for inclusion in the Flyway Site Network. When there is a new nomination or an SIS update, the following sections with an asterisk (*), from Questions 1-14 and Question 30, must be filled or updated at least so that it can justify the international importance of the habitat for migratory waterbirds. 2. The Site Information Sheet is based on the Ramsar Information Sheet. If the site proposed for the Flyway Site Network is an existing Ramsar site then the documentation process can be simplified. 3. Once completed, the Site Information Sheet (and accompanying map(s)) should be submitted to the Flyway Partnership Secretariat. Compilers should provide an electronic (MS Word) copy of the Information Sheet and, where possible, digital versions (e.g. shapefile) of all maps. ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- -

SHOREBIRDS (Charadriiformes*) CARE MANUAL *Does Not Include Alcidae

SHOREBIRDS (Charadriiformes*) CARE MANUAL *Does not include Alcidae CREATED BY AZA CHARADRIIFORMES TAXON ADVISORY GROUP IN ASSOCIATION WITH AZA ANIMAL WELFARE COMMITTEE Shorebirds (Charadriiformes) Care Manual Shorebirds (Charadriiformes) Care Manual Published by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums in association with the AZA Animal Welfare Committee Formal Citation: AZA Charadriiformes Taxon Advisory Group. (2014). Shorebirds (Charadriiformes) Care Manual. Silver Spring, MD: Association of Zoos and Aquariums. Original Completion Date: October 2013 Authors and Significant Contributors: Aimee Greenebaum: AZA Charadriiformes TAG Vice Chair, Monterey Bay Aquarium, USA Alex Waier: Milwaukee County Zoo, USA Carol Hendrickson: Birmingham Zoo, USA Cindy Pinger: AZA Charadriiformes TAG Chair, Birmingham Zoo, USA CJ McCarty: Oregon Coast Aquarium, USA Heidi Cline: Alaska SeaLife Center, USA Jamie Ries: Central Park Zoo, USA Joe Barkowski: Sedgwick County Zoo, USA Kim Wanders: Monterey Bay Aquarium, USA Mary Carlson: Charadriiformes Program Advisor, Seattle Aquarium, USA Sara Perry: Seattle Aquarium, USA Sara Crook-Martin: Buttonwood Park Zoo, USA Shana R. Lavin, Ph.D.,Wildlife Nutrition Fellow University of Florida, Dept. of Animal Sciences , Walt Disney World Animal Programs Dr. Stephanie McCain: AZA Charadriiformes TAG Veterinarian Advisor, DVM, Birmingham Zoo, USA Phil King: Assiniboine Park Zoo, Canada Reviewers: Dr. Mike Murray (Monterey Bay Aquarium, USA) John C. Anderson (Seattle Aquarium volunteer) Kristina Neuman (Point Blue Conservation Science) Sarah Saunders (Conservation Biology Graduate Program,University of Minnesota) AZA Staff Editors: Maya Seaman, MS, Animal Care Manual Editing Consultant Candice Dorsey, PhD, Director of Animal Programs Debborah Luke, PhD, Vice President, Conservation & Science Cover Photo Credits: Jeff Pribble Disclaimer: This manual presents a compilation of knowledge provided by recognized animal experts based on the current science, practice, and technology of animal management. -

Where Have All the Curlews Gone?

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Papers in Ornithology Papers in the Biological Sciences August 1980 Where Have All the Curlews Gone? Paul A. Johnsgard University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciornithology Part of the Ornithology Commons Johnsgard, Paul A., "Where Have All the Curlews Gone?" (1980). Papers in Ornithology. 23. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciornithology/23 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Papers in Ornithology by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Where Have All the Curlews Gone? * foundland and Nova Scotia until early September, when they would Where Have All the Curlews Gone? leave for a nonstop flight to the Lesser Antilles, some 2,000 miles to the south. After a brief lay‐over in the Lesser Antilles, the birds con‐ One species seems to have gone extinct, although occasional tinued south over eastern Brazil and on to Argentina. The majority sightings of the Eskimo curlew keep hopes alive arrived at their winter quarters by mid‐September, concentrating in the grassy pampas south of Buenos Aires. by Paul A. Johnsgard However, fall storms on the Atlantic coast often affected this schedule and itinerary, forcing the birds to hug the North American he morning of September 16, 1932, dawned gray and dismal, shoreline. Large flocks would build up along the Atlantic coast, par‐ with a northeaster in full progress along the coast of Long ticularly in Massachusetts, on Long Island, and down through the Island. -

Mobbing Behaviour in the Shorebirds of North America

-41- NORTHAMERICAN SECTION N--ø.8 Editor Dr. R.I.G. Morrison, Canadian Wildlife Service, 1725 Woodward Drive, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. K1A OE7. (613)-998-4693. Western Region Editor Dr. J.P. Myers, Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, 2593 Life Sciences Building, University of California, Berkeley, California 94720, U.S.A. (415)-642-2893. ANNOUNCEMENTS Colour-marking A number of colour-marking schemes will again be active in 1981 and observers are asked to be on the lookout for birds marked both this summer and in previous years. Details to be noted include species, date, place, colour of any dye and part of bird marked, and colour, number and position of colour-bands and metal band, including whether the bands were located on the 'upper' or 'lower' leg. Where the origin of the bird can be determined, a report may be sent directly to the bander as well as to the U.S. Banding Laboratory, U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, Office of Migratory Bird Management, Laurel, Maryland 20811, U.S.A. The following are some of the schemes known to be operating in 1981 or in recent years - a fuller list is given in WSGBulletin No. 29, N.A. Section No. 6, p. 27. Please contact the Editor if you would like a colour-marking scheme advertised. 1. C.W.S. Studies in James Bay The large-scale shorebird banding program run by the Canadian Wildlife Service in James Bay, Canada, will be continued in 1981. Birds are marked with picric acid and yellow or light blue colour-bands. Full details of sightings should be sent to Dr. -

Pilbara Shorebirds and Seabirds

Shorebirds and seabirds OF THE PILBARA COAST AND ISLANDS Montebello Islands Pilbara Region Dampier Barrow Sholl Island Karratha Island PERTH Thevenard Island Serrurier Island South Muiron Island COASTAL HIGHWAY Onslow Pannawonica NORTH WEST Exmouth Cover: Greater sand plover. This page: Great knot. Photos – Grant Griffin/DBCA Photos – Grant page: Great knot. This Greater sand plover. Cover: Shorebirds and seabirds of the Pilbara coast and islands The Pilbara coast and islands, including the Exmouth Gulf, provide important refuge for a number of shorebird and seabird species. For migratory shorebirds, sandy spits, sandbars, rocky shores, sandy beaches, salt marshes, intertidal flats and mangroves are important feeding and resting habitat during spring and summer, when the birds escape the harsh winter of their northern hemisphere breeding grounds. Seabirds, including terns and shearwaters, use the islands for nesting. For resident shorebirds, including oystercatchers and beach stone-curlews, the islands provide all the food, shelter and undisturbed nesting areas they need. What is a shorebird? Shorebirds, also known as ‘waders’, are a diverse group of birds mostly associated with wetland and coastal habitats where they wade in shallow water and feed along the shore. This group includes plovers, sandpipers, stints, curlews, knots, godwits and oystercatchers. Some shorebirds spend their entire lives in Australia (resident), while others travel long distances between their feeding and breeding grounds each year (migratory). TYPES OF SHOREBIRDS Roseate terns. Photo – Grant Griffin/DBCA Photo – Grant Roseate terns. Eastern curlew Whimbrel Godwit Plover Turnstone Sandpiper Sanderling Diagram – adapted with permission from Ted A Morris Jr. Above: LONG-DISTANCE TRAVELLERS To never experience the cold of winter sounds like a good life, however migratory shorebirds put a lot of effort in achieving their endless summer. -

Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (And 113 Non-Species Taxa) in Accordance with the 62Nd AOU Supplement (2021), Sorted Taxonomically

Four-letter (English Name) and Six-letter (Scientific Name) Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (and 113 Non-Species Taxa) in accordance with the 62nd AOU Supplement (2021), sorted taxonomically Prepared by Peter Pyle and David F. DeSante The Institute for Bird Populations www.birdpop.org ENGLISH NAME 4-LETTER CODE SCIENTIFIC NAME 6-LETTER CODE Highland Tinamou HITI Nothocercus bonapartei NOTBON Great Tinamou GRTI Tinamus major TINMAJ Little Tinamou LITI Crypturellus soui CRYSOU Thicket Tinamou THTI Crypturellus cinnamomeus CRYCIN Slaty-breasted Tinamou SBTI Crypturellus boucardi CRYBOU Choco Tinamou CHTI Crypturellus kerriae CRYKER White-faced Whistling-Duck WFWD Dendrocygna viduata DENVID Black-bellied Whistling-Duck BBWD Dendrocygna autumnalis DENAUT West Indian Whistling-Duck WIWD Dendrocygna arborea DENARB Fulvous Whistling-Duck FUWD Dendrocygna bicolor DENBIC Emperor Goose EMGO Anser canagicus ANSCAN Snow Goose SNGO Anser caerulescens ANSCAE + Lesser Snow Goose White-morph LSGW Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Intermediate-morph LSGI Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Blue-morph LSGB Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Greater Snow Goose White-morph GSGW Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Intermediate-morph GSGI Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Blue-morph GSGB Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Snow X Ross's Goose Hybrid SRGH Anser caerulescens x rossii ANSCAR + Snow/Ross's Goose SRGO Anser caerulescens/rossii ANSCRO Ross's Goose -

The Decline and Fall of the Eskimo Curlew, Or Why Did the Curlew Go

The decline and fall of the Eskimo Curlew, or did the curlew go extaille? by Richard C. Banks 66Thereis no need to look for a probable bush (1912) and Swenk (1916) seems over- incause for the extermination of the whelming,and there can be little reasonable Eskimo Curlew -- the causeis painfully doubtthat overkill was an importantfactor in apparent.... The destructionof this bird was the demiseof the curlewand in the reductionof mainlydue to unrestrictedshooting, market populationsofother species. Yet, the dogmatic huntingand shipment, particularly during the statementsquoted above suggest that any other spring migration in the United States" (For- factors that may have been involved were bush 1912:427). ignored,and indeed these authors barely men- tionedand quickly discarded other postulated &&One neednot look far to find the cause causes.This paper.will analyzethe circum- •Jwhich led to its destruction.... No, stancesof thedecline of the curlew, attempt to therewas only one cause, slaughter by human placeknown mortality factors into perspective, beings, slaughter in Labrador and New and speculatethat other factors unknown to Englandin summerand fall, slaughterin Forbushand Swenkwere significant in that SouthAmerica in winterand slaughter,worst decline. of all, from Texasto Canadain the spring" (Bent 1929:127). LIFE HISTORY hewriting of the authorscited above, and What little waslearned about the biologyof similar conclusionsby Swenk(1916), have the EskimoCurlew before its populationwas led to generalacceptance of the conceptthat reducedvirtually to nil has been summarized excessiveshooting, particularly by market by Forbush (1912), Swenk(1916), Bent (1929), hunters, was the cause of the extationa of the and Greenway(1958). The speciesbred in the Eskimo Curlew, Numenius borealis, near the Arctic, mainly in the Mackenzie District of the end of the 19th century(Greenway 1958, Vin- Northwest Territories of Canada, but also cent 1966, Bureau of Sport Fisheries and westwardand eastwardfor unknown distances, Wildlife1973). -

Birds of Ontario

Birds of Ontario sandilands v2 hi_res.pdf 1 4/28/2010 10:31:32 AM Birds of Ontario: Habitat Requirements, Limiting Factors, and Status 1 Nonpasserines: Waterfowl through Cranes 2 Nonpasserines: Shorebirds through Woodpeckers 3 Passerines: Flycatchers through Waxwings 4 Passerines: Wood-warblers through Old World Sparrows sandilands v2 hi_res.pdf 2 4/28/2010 10:32:12 AM AL SANDILANDS Birds of Ontario Habitat Requirements, Limiting Factors, and Status NONPASSERINES: SHOREBIRDS THROUGH WOODPECKERS With illustrations by Ross James sandilands v2 hi_res.pdf 3 4/28/2010 10:32:12 AM © UBC Press 2010 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior written permission of the publisher, or, in Canada, in the case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, a licence from Access Copyright, www.accesscopyright.ca. 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 5 4 3 2 1 Printed in Canada on acid-free paper Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Sandilands, A.P. (Allan P.) Birds of Ontario: habitat requirements, limiting factors, and status / Al Sandilands; with illustrations by Ross James. Includes bibliographical references and index. Incomplete contents: v. 1. Nonpasserines: waterfowl through cranes. – v. 2. Nonpasserines: shorebirds through woodpeckers. ISBN 978-0-7748-1066-1 (bound: v. 1) – ISBN 978-0-7748-1762-2 (bound: v. 2) 1. Birds – Habitat – Ontario. 2. Birds – Effect of habitat modification on – Ontario. 3. Bird populations – Ontario. I. Title. QL685.5.O5S35 2005 598’.09713 C2005-900826-1 E-book ISBNs: 978-0-7748-1764-6 (pdf); 978-0-7748-5943-1 (e-pub) UBC Press gratefully acknowledges the financial support for our publishing program of the Government of Canada (through the Canada Book Fund), the Canada Council for the Arts, and the British Columbia Arts Council.