Canada's 4Th National Report to The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FISH LIST WISH LIST: a Case for Updating the Canadian Government’S Guidance for Common Names on Seafood

FISH LIST WISH LIST: A case for updating the Canadian government’s guidance for common names on seafood Authors: Christina Callegari, Scott Wallace, Sarah Foster and Liane Arness ISBN: 978-1-988424-60-6 © SeaChoice November 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS GLOSSARY . 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY . 4 Findings . 5 Recommendations . 6 INTRODUCTION . 7 APPROACH . 8 Identification of Canadian-caught species . 9 Data processing . 9 REPORT STRUCTURE . 10 SECTION A: COMMON AND OVERLAPPING NAMES . 10 Introduction . 10 Methodology . 10 Results . 11 Snapper/rockfish/Pacific snapper/rosefish/redfish . 12 Sole/flounder . 14 Shrimp/prawn . 15 Shark/dogfish . 15 Why it matters . 15 Recommendations . 16 SECTION B: CANADIAN-CAUGHT SPECIES OF HIGHEST CONCERN . 17 Introduction . 17 Methodology . 18 Results . 20 Commonly mislabelled species . 20 Species with sustainability concerns . 21 Species linked to human health concerns . 23 Species listed under the U .S . Seafood Import Monitoring Program . 25 Combined impact assessment . 26 Why it matters . 28 Recommendations . 28 SECTION C: MISSING SPECIES, MISSING ENGLISH AND FRENCH COMMON NAMES AND GENUS-LEVEL ENTRIES . 31 Introduction . 31 Missing species and outdated scientific names . 31 Scientific names without English or French CFIA common names . 32 Genus-level entries . 33 Why it matters . 34 Recommendations . 34 CONCLUSION . 35 REFERENCES . 36 APPENDIX . 39 Appendix A . 39 Appendix B . 39 FISH LIST WISH LIST: A case for updating the Canadian government’s guidance for common names on seafood 2 GLOSSARY The terms below are defined to aid in comprehension of this report. Common name — Although species are given a standard Scientific name — The taxonomic (Latin) name for a species. common name that is readily used by the scientific In nomenclature, every scientific name consists of two parts, community, industry has adopted other widely used names the genus and the specific epithet, which is used to identify for species sold in the marketplace. -

Pleuronectidae, Poecilopsettidae, Achiridae, Cynoglossidae

1536 Glyptocephalus cynoglossus (Linnaeus, 1758) Pleuronectidae Witch flounder Range: Both sides of North Atlantic Ocean; in the western North Atlantic from Strait of Belle Isle to Cape Hatteras Habitat: Moderately deep water (mostly 45–330 m), deepest in southern part of range; found on mud, muddy sand or clay substrates Spawning: May–Oct in Gulf of Maine; Apr–Oct on Georges Bank; Feb–Jul Meristic Characters in Middle Atlantic Bight Myomeres: 58–60 Vertebrae: 11–12+45–47=56–59 Eggs: – Pelagic, spherical Early eggs similar in size Dorsal fin rays: 97–117 – Diameter: 1.2–1.6 mm to those of Gadus morhua Anal fin rays: 86–102 – Chorion: smooth and Melanogrammus aeglefinus Pectoral fin rays: 9–13 – Yolk: homogeneous Pelvic fin rays: 6/6 – Oil globules: none Caudal fin rays: 20–24 (total) – Perivitelline space: narrow Larvae: – Hatching occurs at 4–6 mm; eyes unpigmented – Body long, thin and transparent; preanus length (<33% TL) shorter than in Hippoglossoides or Hippoglossus – Head length increases from 13% SL at 6 mm to 22% SL at 42 mm – Body depth increases from 9% SL at 6 mm to 30% SL at 42 mm – Preopercle spines: 3–4 occur on posterior edge, 5–6 on lateral ridge at about 16 mm, increase to 17–19 spines – Flexion occurs at 14–20 mm; transformation occurs at 22–35 mm (sometimes delayed to larger sizes) – Sequence of fin ray formation: C, D, A – P2 – P1 – Pigment intensifies with development: 6 bands on body and fins, 3 major, 3 minor (see table below) Glyptocephalus cynoglossus Hippoglossoides platessoides Total myomeres 58–60 44–47 Preanus length <33%TL >35%TL Postanal pigment bars 3 major, 3 minor 3 with light scattering between Finfold pigment Bars extend onto finfold None Flexion size 14–20 mm 9–19 mm Ventral pigment Scattering anterior to anus Line from anus to isthmus Early Juvenile: Occurs in nursery habitats on continental slope E. -

What Their Stories Tell Us: Research Findings from the Sisters In

What Their Stories Tell Us Research findings from the Sisters In Spirit initiative Sisters In Spirit 2010 Research Findings Aboriginal women and girls are strong and beautiful. They are our mothers, our daughters, our sisters, aunties, and grandmothers. Acknowledgments This research would not have been possible without the stories shared by families and communities of missing and murdered Aboriginal women and girls. The Native Women’s Association of Canada (NWAC) is indebted to the many families, communities, and friends who have lost a loved one. We are continually amazed by your strength, generosity and courage. We thank our Elders and acknowledge First Nations, Inuit and Métis communities for their strength and resilience. We acknowledge the dedication and commitment of community and grassroots researchers, advocates, and activists who have been instrumental in raising awareness about this issue. We also acknowledge the hard work of service providers and all those working towards ending violence against Aboriginal women in Canada. We appreciate the many community, provincial, national and Aboriginal organizations, and federal departments that supported this work, particularly Status of Women Canada. Finally, NWAC would like thank all those who worked on the Sisters In Spirit initiative over the past five years. These contributions have been invaluable and have helped shape the nature and findings of this report. This research report is dedicated to all Aboriginal women and girls who are missing or have been lost to violence. Sisters In Spirit 2010 Research Findings Native Women’s Association of Canada Incorporated in 1974, the Native Women’s Association of Canada (NWAC) is founded on the collective goal to enhance, promote, and foster the social, economic, cultural and political well- being of Aboriginal women within Aboriginal communities and Canadian society. -

Special Report 10-02 Compendium of Long-Term Wildlife Monitoring

ncasi NATIONAL COUNCIL FOR AIR AND STREAM IMPROVEMENT COMPENDIUM OF LONG-TERM WILDLIFE MONITORING PROGRAMS IN CANADA SPECIAL REPORT NO. 10-02 OCTOBER 2010 by Sonya Lévesque Saguenay, Quebec Introduction by Darren Sleep, Ph.D. NCASI Montreal, Quebec Acknowledgments The author acknowledges the assistance of the various program managers across Canada, who were kind enough to take some of their time to answer questions and to review, comment upon, and edit project descriptions. A special thanks to Denis Lepage, from Bird Studies Canada, for his collaboration and interest. The author also thanks Darren Sleep and Kirsten Vice, from the National Council for Air and Stream Improvement, for their trust and help. For more information about this research, contact: Darren J.H. Sleep, Ph.D. Kirsten Vice Senior Forest Ecologist Vice President, Canadian Operations NCASI NCASI P.O. Box 1036, Station B P.O. Box 1036, Station B Montreal, QC H3B 3K5 Canada Montreal, QC H3B 3K5 Canada (514) 286-9690 (514) 286-9111 [email protected] [email protected] For information about NCASI publications, contact: Publications Coordinator NCASI P.O. Box 13318 Research Triangle Park, NC 27709-3318 (919) 941-6400 [email protected] Cite this report as: National Council for Air and Stream Improvement, Inc. (NCASI). 2010. Compendium of long-term wildlife monitoring programs in Canada. Special Report No. 10-02. Research Triangle Park, N.C.: National Council for Air and Stream Improvement, Inc. © 2010 by the National Council for Air and Stream Improvement, Inc. ncasi serving the environmental research needs of the forest products industry since 1943 PRESIDENT’S NOTE Wildlife monitoring can be a reliable source of information that contributes to effective forest management. -

Newsletter Varnish

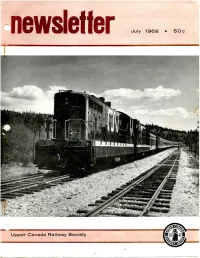

The Cover The outlook's bleak for the future of passenger trains in Newfoundland, as our report on page 78 indicates. In a matter of months, buses will appear on the St. John's- Port aux Basques run, phasing out CN's narrow gauge newsletter varnish. Here's the easthound Caribou waiting for its westbound counterpart at Cooke siding in June, 1967. — Tom Henry Number 270 Published monthly by the Upper Canada Railway Society, Inc., Box 122, Terminal A, Toronto, Ont. James A. Brown, Editor Coming Events :.:.:.;-:.:.;.:.:.:.:.:.:.;.;.:.:.x-:.;'X-:':':-;-:-:'X-:w^^^^^ Regular meetings of the Society are held on the third Friday of Authorized as Second Class Matter by the Post Office Department, each month (except July and August) at 589 Mt. Pleasant Road, Ottawa, Ont. and for payment of postage in cash. Toronto, Ontario. 8.00 p.m. Members are asked to give the Society at least five weeks notice of address changes. Aug 16: Summer meeting and social night at 589 Mt. (Fri) Pleasant Road, featuring refreshments and pro• fessional films of rail interest. Sept 20: Regular Meeting. Please address NEWSLETTER contributions to the Editor at (Fri) 3 Bromley Crescent, Bramalea, Ontario. No responsibility is assumed for loss or nonreturn of material. All other Society business, including membership inquiries, should be addressed to UCRS, Box 122, Terminal A, Toronto, Ontario. Contributors: John Bromley, Reg Button, Tom Henry, Bill Hood, George Horner, Omer Lavallee, Boh McMann, Ernie Modler, Steve Munro, John Thompson, Ted Wickson. Production: John Bromley, Tom Henry, Omer Lavallee. Distribution: Chas. Bridges, George Meek, Bill Miller, Steve Munro, John Thompson, Ted Wickson. -

Wild Species 2010 the GENERAL STATUS of SPECIES in CANADA

Wild Species 2010 THE GENERAL STATUS OF SPECIES IN CANADA Canadian Endangered Species Conservation Council National General Status Working Group This report is a product from the collaboration of all provincial and territorial governments in Canada, and of the federal government. Canadian Endangered Species Conservation Council (CESCC). 2011. Wild Species 2010: The General Status of Species in Canada. National General Status Working Group: 302 pp. Available in French under title: Espèces sauvages 2010: La situation générale des espèces au Canada. ii Abstract Wild Species 2010 is the third report of the series after 2000 and 2005. The aim of the Wild Species series is to provide an overview on which species occur in Canada, in which provinces, territories or ocean regions they occur, and what is their status. Each species assessed in this report received a rank among the following categories: Extinct (0.2), Extirpated (0.1), At Risk (1), May Be At Risk (2), Sensitive (3), Secure (4), Undetermined (5), Not Assessed (6), Exotic (7) or Accidental (8). In the 2010 report, 11 950 species were assessed. Many taxonomic groups that were first assessed in the previous Wild Species reports were reassessed, such as vascular plants, freshwater mussels, odonates, butterflies, crayfishes, amphibians, reptiles, birds and mammals. Other taxonomic groups are assessed for the first time in the Wild Species 2010 report, namely lichens, mosses, spiders, predaceous diving beetles, ground beetles (including the reassessment of tiger beetles), lady beetles, bumblebees, black flies, horse flies, mosquitoes, and some selected macromoths. The overall results of this report show that the majority of Canada’s wild species are ranked Secure. -

OECD/IMHE Project Self Evaluation Report: Atlantic Canada, Canada

OECD/IMHE Project Supporting the Contribution of Higher Education Institutions to Regional Development Self Evaluation Report: Atlantic Canada, Canada Wade Locke (Memorial University), Elizabeth Beale (Atlantic Provinces Economic Council), Robert Greenwood (Harris Centre, Memorial University), Cyril Farrell (Atlantic Provinces Community College Consortium), Stephen Tomblin (Memorial University), Pierre-Marcel Dejardins (Université de Moncton), Frank Strain (Mount Allison University), and Godfrey Baldacchino (University of Prince Edward Island) December 2006 (Revised March 2007) ii Acknowledgements This self-evaluation report addresses the contribution of higher education institutions (HEIs) to the development of the Atlantic region of Canada. This study was undertaken following the decision of a broad group of partners in Atlantic Canada to join the OECD/IMHE project “Supporting the Contribution of Higher Education Institutions to Regional Development”. Atlantic Canada was one of the last regions, and the only North American region, to enter into this project. It is also one of the largest groups of partners to participate in this OECD project, with engagement from the federal government; four provincial governments, all with separate responsibility for higher education; 17 publicly funded universities; all colleges in the region; and a range of other partners in economic development. As such, it must be appreciated that this report represents a major undertaking in a very short period of time. A research process was put in place to facilitate the completion of this self-evaluation report. The process was multifaceted and consultative in nature, drawing on current data, direct input from HEIs and the perspectives of a broad array of stakeholders across the region. An extensive effort was undertaken to ensure that input was received from all key stakeholders, through surveys completed by HEIs, one-on-one interviews conducted with government officials and focus groups conducted in each province which included a high level of private sector participation. -

Regional Geology of the Scotian Basin

REGIONAL GEOLOGY OF THE SCOTIAN BASIN David E. Brown, CNSOPB, 2008 INTRODUCTION The Scotian Basin is a classic passive, mostly non-volcanic, conjugate margin. It represents over 250 million years of continuous sedimentation recording the region's dynamic geological history from the initial opening of the Atlantic Ocean to the recent post-glacial deposition. The basin is located on the northeastern flank of the Appalachian Orogen and covers an area of approximately 300,000 km2 with an estimated maximum sediment thickness of about 24 kilometers. The continental-size drainage system of the paleo-St. Lawrence River provided a continuous supply of sediments that accumulated in a number of complex, interconnected subbasins. The basin's stratigraphic succession contains early synrift continental, postrift carbonate margin, fluvial-deltaic-lacustrine, shallow marine and deepwater depositional systems. PRERIFT The Scotian Basin is located offshore Nova Scotia where it extends for 1200 km from the Yarmouth Arch / United States border in the southwest to the Avalon Uplift on the Grand Banks of Newfoundland in the northeast (Figure 1). With an average breadth of 250 km, the total area of the basin is approximately 300,000 km2. Half of the basin lies on the present-day continental shelf in water depths less than 200 m with the other half on the continental slope in water depths from 200 to >4000 m. The Scotian Basin formed on a passive continental margin that developed after North America rifted and separated from the African continent during the breakup of Pangea (Figure 2). Its tectonic elements consist of a series of platforms and depocentres separated by basement ridges and/or major basement faults. -

Canadian Rail No162 1965

<:;an..adi J~mnn Number 162 / Janua r y 1965 Cereal box coupons and soap package enclosures do not general ly excite much enthusiasm from the editor of 'Canadian Rail', but we must admit we are looking forward with some eagerness to comp leting our collection of RAILWAY MUGS currently being distribut e d by the Quaker Oats Company, in their specially-marked packages of Quaker Oats. This series of twelve hot chocolate mugs depicts the develop - ment of the steam locomotive in Canada from the 0-6-0 "Samson", to the CPR 2-10-4 #8000. The mugs are being offered by the Quaker Oats Company of Cana da to salute Canada's Centennial, and the part played by the rail ways and their steam locomotives in furthering the pro ~ ress of the nation. Each cup pictures an authentic locomotive design -- one shows a Canadian Northern 2-8-0, a type of locomotive that made a major contribution to the country's prairie economy by moving grain from the Western provinces to the Lakehead -- another shows one of the Canadian Pacific's ubiquitous D-10 engines. There are 12 different locomotives in the series - each a col lector's item. The reproductions are precisely etched in decora tive colours and trimmed with 22k gold. Canadian Rail Par,e 3 &eee_eIPIrWB __waBS} -- E.L.Modler. Once a Ga in this year, the Canadian National Railways has leased a number of road switcher type diesels from the Duluth, Missabe and Iron Range Railroad. :,ihile last year all the uni ts leased from the D.I.L& I.R. -

THE SPECIAL COUNCILS of LOWER CANADA, 1838-1841 By

“LE CONSEIL SPÉCIAL EST MORT, VIVE LE CONSEIL SPÉCIAL!” THE SPECIAL COUNCILS OF LOWER CANADA, 1838-1841 by Maxime Dagenais Dissertation submitted to the School of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the PhD degree in History. Department of History Faculty of Arts Université d’Ottawa\ University of Ottawa © Maxime Dagenais, Ottawa, Canada, 2011 ii ABSTRACT “LE CONSEIL SPÉCIAL EST MORT, VIVE LE CONSEIL SPÉCIAL!” THE SPECIAL COUNCILS OF LOWER CANADA, 1838-1841 Maxime Dagenais Supervisor: University of Ottawa, 2011 Professor Peter Bischoff Although the 1837-38 Rebellions and the Union of the Canadas have received much attention from historians, the Special Council—a political body that bridged two constitutions—remains largely unexplored in comparison. This dissertation considers its time as the legislature of Lower Canada. More specifically, it examines its social, political and economic impact on the colony and its inhabitants. Based on the works of previous historians and on various primary sources, this dissertation first demonstrates that the Special Council proved to be very important to Lower Canada, but more specifically, to British merchants and Tories. After years of frustration for this group, the era of the Special Council represented what could be called a “catching up” period regarding their social, commercial and economic interests in the colony. This first section ends with an evaluation of the legacy of the Special Council, and posits the theory that the period was revolutionary as it produced several ordinances that changed the colony’s social, economic and political culture This first section will also set the stage for the most important matter considered in this dissertation as it emphasizes the Special Council’s authoritarianism. -

A Lesson in Stone: Examining Patterns of Lithic Resource Use and Craft-Learning in the Minas Basin Region of Nova Scotia By

A Lesson in Stone: Examining Patterns of Lithic Resource Use and Craft-learning in the Minas Basin Region of Nova Scotia By © Catherine L. Jalbert A thesis submitted to the School of Graduate Studies for partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. Department of Archaeology Memorial University of Newfoundland May 2011 St. John’s Newfoundland Abstract Examining the Late Woodland (1500-450 BP) quarry/workshop site of Davidson Cove, located in the Minas Basin region of Nova Scotia, a sample of debitage and a collection of stone implements appear to provide correlates of the novice and raw material production practices. Many researchers have hypothesized that lithic materials discovered at multiple sites within the region originated from the outcrop at Davidson Cove, however little information is available on lithic sourcing of the Minas Basin cherts. Considering the lack of archaeological knowledge concerning lithic procurement and production, patterns of resource use among the prehistoric indigenous populations in this region of Nova Scotia are established through the analysis of existing collections. By analysing the lithic materials quarried and initially reduced at the quarry/workshop with other contemporaneous assemblages from the region, an interpretation of craft-learning can be situated in the overall technological organization and subsistence strategy for the study area. ii Acknowledgements It is a pleasure to thank all those who made this thesis achievable. First and foremost, this thesis would not have been possible without the guidance and support provided by my supervisor, Dr. Michael Deal. His insight throughout the entire thesis process was invaluable. I would also like to thank Dr. -

Eight History Lessons Grade 8

Eight History Lessons Grade 8 Submitted By: Rebecca Neadow 05952401 Submitted To: Ted Christou CURR 355 Submitted On: November 15, 2013 INTRODUCTORY ACTIVITY OVERVIEW This is an introductory assignment for students in a grade 8 history class dealing with the Red River Settlement. LEARNING GOAL AND FOCUSING QUESTION - During this lesson students activate their prior knowledge and connections to gain a deeper understanding of the word Rebellion and what requires to set up a new settlement. CURRICULUM EXPECTATIONS - Interpret and analyse information and evidence relevant to their investigations, using a variety of tools. MATERIALS - There are certain terms students will need to understand within this lesson. They are: 1. Emigrate – to leave one place or country in order to settle in another 2. Lord Selkirk – Scottish born 5th Earl of Selkirk, used his money to buy the Hudson’s Bay Company in order to get land to establish a settlement on the Red River in Rupert’s Land in 1812 3. Red River – a river that flows North Dakota north into Lake Winnipeg 4. Exonerate – to clear or absolve from blame or a criminal charge 5. Hudson’s Bay Company – an English company chartered in 1670 to trade in all parts of North America drained by rivers flowing into Hudson’s Bay 6. North West Company – a fur trading business headquartered in Montréal from 1779 to 1821 which competed, often violently, with the Hudson’s Bay Company until it merged with the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1821 7. Rupert’s Land – the territories granted by Charles II of England to the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1670 and ceded to the Canadian government in 1870 - For research: textbook, computer, dictionaries or whatever you have available to you.