Gibbon Journal Nr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Description of a New Species of Hoolock Gibbon (Primates: Hylobatidae) Based

1 Title: Description of a new species of Hoolock gibbon (Primates: Hylobatidae) based 2 on integrative taxonomy 3 Peng-Fei Fan1,2#,*, Kai He3,4,#, *, Xing Chen3,#, Alejandra Ortiz5,6,7, Bin Zhang3, Chao 4 Zhao8, Yun-Qiao Li9, Hai-Bo Zhang10, Clare Kimock5,6, Wen-Zhi Wang3, Colin 5 Groves11, Samuel T. Turvey12, Christian Roos13, Kris M. Helgen4, Xue-Long Jiang3* 6 7 8 9 1. School of Life Sciences, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, 510275, P.R. China 10 2. Institute of Eastern-Himalaya Biodiversity Research, Dali University, Dali, 671003, 11 P.R. China 12 3. Kunming Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Kunming, 650223, 13 P.R. China 14 4. Department of Vertebrate Zoology, National Museum of Natural History, 15 Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., 20013, USA 16 5. Center for the Study of Human Origins, Department of Anthropology, New York 17 University, New York, 10003, USA 18 6. New York Consortium in Evolutionary Primatology (NYCEP), New York, 10024, 19 USA 20 7. Institute of Human Origins, School of Human Evolution and Social Change, 21 Arizona State University, Tempe, 85281, USA. 22 8. Cloud Mountain Conservation, Dali, 671003, P.R. China 1 23 9. Kunming Zoo, Kunming, 650021, P. R. China 24 10. Beijing Zoo, Beijing, 100044, P.R. China 25 11. School of Archaeology & Anthropology, Australian National University, Acton, 26 ACT 2601, Australia 27 12. Institute of Zoology, Zoological Society of London, NW1 4RY, London, UK 28 13. Gene Bank of Primates and Primate Genetics Laboratory, German Primate Center, 29 Leibniz Institute for Primate Research, Kellnerweg 4, 37077 Göttingen, Germany 30 31 32 Short title: A new species of small ape 33 #: These authors contributed equally to this work. -

Gibbon Journal Nr

Gibbon Journal Nr. 5 – May 2009 Gibbon Conservation Alliance ii Gibbon Journal Nr. 5 – 2009 Impressum Gibbon Journal 5, May 2009 ISSN 1661-707X Publisher: Gibbon Conservation Alliance, Zürich, Switzerland http://www.gibbonconservation.org Editor: Thomas Geissmann, Anthropological Institute, University Zürich-Irchel, Universitätstrasse 190, CH–8057 Zürich, Switzerland. E-mail: [email protected] Editorial Assistants: Natasha Arora and Andrea von Allmen Cover legend Western hoolock gibbon (Hoolock hoolock), adult female, Yangon Zoo, Myanmar, 22 Nov. 2008. Photo: Thomas Geissmann. – Westlicher Hulock (Hoolock hoolock), erwachsenes Weibchen, Yangon Zoo, Myanmar, 22. Nov. 2008. Foto: Thomas Geissmann. ©2009 Gibbon Conservation Alliance, Switzerland, www.gibbonconservation.org Gibbon Journal Nr. 5 – 2009 iii GCA Contents / Inhalt Impressum......................................................................................................................................................................... i Instructions for authors................................................................................................................................................... iv Gabriella’s gibbon Simon M. Cutting .................................................................................................................................................1 Hoolock gibbon and biodiversity survey and training in southern Rakhine Yoma, Myanmar Thomas Geissmann, Mark Grindley, Frank Momberg, Ngwe Lwin, and Saw Moses .....................................4 -

Alan Moore's Miracleman: Harbinger of the Modern Age of Comics

Alan Moore’s Miracleman: Harbinger of the Modern Age of Comics Jeremy Larance Introduction On May 26, 2014, Marvel Comics ran a full-page advertisement in the New York Times for Alan Moore’s Miracleman, Book One: A Dream of Flying, calling the work “the series that redefined comics… in print for the first time in over 20 years.” Such an ad, particularly one of this size, is a rare move for the comic book industry in general but one especially rare for a graphic novel consisting primarily of just four comic books originally published over thirty years before- hand. Of course, it helps that the series’ author is a profitable lumi- nary such as Moore, but the advertisement inexplicably makes no reference to Moore at all. Instead, Marvel uses a blurb from Time to establish the reputation of its “new” re-release: “A must-read for scholars of the genre, and of the comic book medium as a whole.” That line came from an article written by Graeme McMillan, but it is worth noting that McMillan’s full quote from the original article begins with a specific reference to Moore: “[Miracleman] represents, thanks to an erratic publishing schedule that both predated and fol- lowed Moore’s own Watchmen, Moore’s simultaneous first and last words on ‘realism’ in superhero comics—something that makes it a must-read for scholars of the genre, and of the comic book medium as a whole.” Marvel’s excerpt, in other words, leaves out the very thing that McMillan claims is the most important aspect of Miracle- man’s critical reputation as a “missing link” in the study of Moore’s influence on the superhero genre and on the “medium as a whole.” To be fair to Marvel, for reasons that will be explained below, Moore refused to have his name associated with the Miracleman reprints, so the company was legally obligated to leave his name off of all advertisements. -

10 Sota3 Chapter 7 REV11

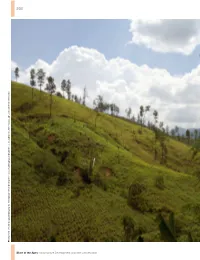

200 Until recently, quantifying rates of tropical forest destruction was challenging and laborious. © Jabruson 2017 (www.jabruson.photoshelter.com) forest quantifying rates of tropical Until recently, Photo: State of the Apes Infrastructure Development and Ape Conservation 201 CHAPTER 7 Mapping Change in Ape Habitats: Forest Status, Loss, Protection and Future Risk Introduction This chapter examines the status of forested habitats used by apes, charismatic species that are almost exclusively forest-dependent. With one exception, the eastern hoolock, all ape species and their subspecies are classi- fied as endangered or critically endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) (IUCN, 2016c). Since apes require access to forested or wooded land- scapes, habitat loss represents a major cause of population decline, as does hunting in these settings (Geissmann, 2007; Hickey et al., 2013; Plumptre et al., 2016b; Stokes et al., 2010; Wich et al., 2008). Until recently, quantifying rates of trop- ical forest destruction was challenging and laborious, requiring advanced technical Chapter 7 Status of Apes 202 skills and the analysis of hundreds of satel- for all ape subspecies (Geissmann, 2007; lite images at a time (Gaveau, Wandono Tranquilli et al., 2012; Wich et al., 2008). and Setiabudi, 2007; LaPorte et al., 2007). In addition, the chapter projects future A new platform, Global Forest Watch habitat loss rates for each subspecies and (GFW), has revolutionized the use of satel- uses these results as one measure of threat lite imagery, enabling the first in-depth to their long-term survival. GFW’s new analysis of changes in forest availability in online forest monitoring and alert system, the ranges of 22 great ape and gibbon spe- entitled Global Land Analysis and Dis- cies, totaling 38 subspecies (GFW, 2014; covery (GLAD) alerts, combines cutting- Hansen et al., 2013; IUCN, 2016c; Max Planck edge algorithms, satellite technology and Insti tute, n.d.-b). -

Gibbon Classification : the Issue of Species and Subspecies

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 1988 Gibbon classification : the issue of species and subspecies Erin Lee Osterud Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Biological and Physical Anthropology Commons, and the Genetics and Genomics Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Osterud, Erin Lee, "Gibbon classification : the issue of species and subspecies" (1988). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 3925. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.5809 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Erin Lee Osterud for the Master of Arts in Anthropology presented July 18, 1988. Title: Gibbon Classification: The Issue of Species and Subspecies. APPROVED BY MEM~ OF THE THESIS COMMITTEE: Marc R. Feldesman, Chairman Gibbon classification at the species and subspecies levels has been hotly debated for the last 200 years. This thesis explores the reasons for this debate. Authorities agree that siamang, concolor, kloss and hoolock are species, while there is complete lack of agreement on lar, agile, moloch, Mueller's and pileated. The disagreement results from the use and emphasis of different character traits, and from debate on the occurrence and importance of gene flow. GIBBON CLASSIFICATION: THE ISSUE OF SPECIES AND SUBSPECIES by ERIN LEE OSTERUD A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in ANTHROPOLOGY Portland State University 1989 TO THE OFFICE OF GRADUATE STUDIES: The members of the Committee approve the thesis of Erin Lee Osterud presented July 18, 1988. -

Nomascus Hainanus) We Conducted a Long-Term Dietary Composition Survey in Bawangling National Nature Reserve, Hainan Island, China from 2002 to 2014

NORTH-WESTERN JOURNAL OF ZOOLOGY 14 (2): 213-219 ©NWJZ, Oradea, Romania, 2018 Article No.: e171703 http://biozoojournals.ro/nwjz/index.html Thirteen years observation on diet composition of Hainan gibbons (Nomascushainanus) Huaiqing DENG and Jiang ZHOU* School of Life Sciences, Guizhou Normal University, Guiyang, Guizhou, 550001, China E-mail: [email protected] *Corresponding author, J. Zhou, Tel:+8613985463226, E-mail: [email protected] Received: 08. April 2017 / Accepted: 27. July 2017 / Available online: 27. July 2017 / Printed: December 2018 Abstract. Researches on diets and feeding behavior of endangered species are critical to understand ecological adaptations and develop conservation strategies. To document the diet of the Hainan gibbon (Nomascus hainanus) we conducted a long-term dietary composition survey in Bawangling National Nature Reserve, Hainan Island, China from 2002 to 2014. Transects and quadrants were established to monitor plant phenology and to count tree species. Tracking survey and scan-sampling method were used to record the feeding species and feeding time of Hainan Gibbon. Our results showed that Hainan gibbons’ habitat vegetation structure is tropical montane evergreen forest dominated by Lauraceae species while Dipterocarpaceae, Leguminosae and Ficusare rare. Hainan gibbons consume 133 plant species across 83 genera and 51 families. Hainan gibbons consumed more Lauraceae and Myrtaceae plant species than other plant species, whereas their consumption of leguminous species was little and with no Dipterocarpaceae compared to other gibbons. Furthermore, we classified the food plants as different feeding parts and confirmed that this gibbon species is a main fruits eater particularly during the wet season (114 species,64.8% feeding time), meanwhile we also observed five species of animal foods. -

Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours

i Being a Superhero is Amazing, Everyone Should Try It: Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Humanities 2021 ii THESIS DECLARATION I, Kevin Chiat, certify that: This thesis has been substantially accomplished during enrolment in this degree. This thesis does not contain material which has been submitted for the award of any other degree or diploma in my name, in any university or other tertiary institution. In the future, no part of this thesis will be used in a submission in my name, for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of The University of Western Australia and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint-award of this degree. This thesis does not contain any material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. This thesis does not violate or infringe any copyright, trademark, patent, or other rights whatsoever of any person. This thesis does not contain work that I have published, nor work under review for publication. Signature Date: 17/12/2020 ii iii ABSTRACT Since the development of the superhero genre in the late 1930s it has been a contentious area of cultural discourse, particularly concerning its depictions of gender politics. A major critique of the genre is that it simply represents an adolescent male power fantasy; and presents a world view that valorises masculinist individualism. -

SILVERY GIBBON PROJECT Newsletterthe Page 1 September 2013 SILVERY GIBBON PROJECT

SILVERY GIBBON PROJECT NEWSLETTERThe Page 1 September 2013 SILVERY GIBBON PROJECT PO BOX 335 COMO 6952 WESTERN AUSTRALIA Website: www.silvery.org.au E-mail: [email protected] Phone: 0438992325 September 2013 Agile Gibbons, Siamangs, Sunbears, Clouded Leopards and even Sumatran Tigers, the area lies PRESIDENT’S REPORT adjacent to a larger protected forest and is also the location of Kalaweit Conservation Centre. We Dear Members and Friends hope to be able to provide additional support to this important project into the future. Keep an eye We are excited to report that the release of on our Facebook page for updates on camera trap Sadewa and Kiki in June went very well and they images from Supayang. continue to thrive in the forest. They are proving a little challenging for the monitoring team to keep Back in Perth, the SGP team is gearing up for our up with but thanks to their morning call the team Art Auction which will be held on October 26. are still able to locate them most days. Please Once again we have secured some amazing read the update on their release on page 4. pieces and the generosity of artists is truly inspiring. Be sure to get your tickets early as this event may sell out. We also have some exciting projects underway with Wildlife Asia. You can find out more about our crowd funding project on page 5. It was certainly an honour to be present at the release, which was the culmination of many years hard work for the Java Gibbon Centre (JGC) team. -

SILVERY GIBBON PROJECT Newsletterthe Page 1 March 2013 SILVERY GIBBON PROJECT

SILVERY GIBBON PROJECT NEWSLETTERThe Page 1 March 2013 SILVERY GIBBON PROJECT PO BOX 335 COMO 6952 WESTERN AUSTRALIA Website: www.silvery.org.au E-mail: [email protected] Phone: 0438992325 March 2013 PRESIDENT’S REPORT I was able to visit JGC in January with some guests, including a local sponsor. It was very promising to see financial support arising for the Dear Members and Friends project from within Indonesia. Well we have kicked off the year with a very successful fundraising campaign that many of you participated in. We came up with the Go Without for Gibbons concept quite a few years back but social media has finally given us the opportunity to promote the idea effectively and actually turn it into some much needed funds for us. Thank you so much to all of you who went without your luxuries for February and made donations to Silvery Gibbon Project (SGP) instead. The campaign culminated with a Comedy Night on March 1 which was lots of fun with plenty of „indulging‟ was had by all . (See page 6). Clare travelling to JGC with Dr Ben Rawson (FFI) We are excited to report this month on the I am heading off again in March to lead the establishment of a new release program for Javan Wildlife Asia Big 5 Tour. This will be a once in a gibbons (Silvery gibbons) and we are looking to lifetime opportunity for participants to visit secure considerable funding to support this conservation projects for Orangutans, Sunbears, project. (See Page 2). Despite the tragic events Sumatran Rhino, Elephants and of course Javan surrounding the hunting of Jeffrey in 2012, we still gibbon. -

Orang Utan and Gibbons Still in Business

IN FULL SWING: AN ASSESSMENT OF TRADE IN ORANG-UTANS AND GIBBONS ON JAVA AND BALI,INDONESIA VINCENT NIJMAN A TRAFFIC SOUTHEAST ASIA REPORT TRAFFIC SOUTHEAST ASIA Published by TRAFFIC Southeast Asia, Petaling Jaya, Selangor, Malaysia © 2005 TRAFFIC Southeast Asia All rights reserved. All material appearing in this publication is copyrighted and may be produced with permission. Any reproduction in full or in part of this publication must credit TRAFFIC Southeast Asia as the copyright owner. The views of the authors expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of the TRAFFIC Network, WWF or IUCN. The designations of geographical entities in this publication, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of TRAFFIC or its supporting organizations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The TRAFFIC symbol copyright and Registered Trademark ownership is held by WWF, TRAFFIC is a joint programme of WWF and IUCN. Layout by Noorainie Awang Anak, TRAFFIC Southeast Asia Suggested citation: Vincent Nijman (2005). In Full Swing: An Assessment of trade in Orang-utans and Gibbons on Java and Bali, Indonesia. TRAFFIC Southeast Asia ISBN 983-3393-00-4 Photograph credit: Orang-utan, Pongo pygmaeus, Sepilok Orang-utan Rehabilitation Centre, Sabah, Malaysia (WWF-Malaysia/Cede Prudente) IN FULL SWING: AN ASSESSMENT OF TRADE IN ORANG-UTANS AND GIBBONS ON JAVA AND BALI,INDONESIA -

(“Spider-Man”) Cr

PRIVILEGED ATTORNEY-CLIENT COMMUNICATION EXECUTIVE SUMMARY SECOND AMENDED AND RESTATED LICENSE AGREEMENT (“SPIDER-MAN”) CREATIVE ISSUES This memo summarizes certain terms of the Second Amended and Restated License Agreement (“Spider-Man”) between SPE and Marvel, effective September 15, 2011 (the “Agreement”). 1. CHARACTERS AND OTHER CREATIVE ELEMENTS: a. Exclusive to SPE: . The “Spider-Man” character, “Peter Parker” and essentially all existing and future alternate versions, iterations, and alter egos of the “Spider- Man” character. All fictional characters, places structures, businesses, groups, or other entities or elements (collectively, “Creative Elements”) that are listed on the attached Schedule 6. All existing (as of 9/15/11) characters and other Creative Elements that are “Primarily Associated With” Spider-Man but were “Inadvertently Omitted” from Schedule 6. The Agreement contains detailed definitions of these terms, but they basically conform to common-sense meanings. If SPE and Marvel cannot agree as to whether a character or other creative element is Primarily Associated With Spider-Man and/or were Inadvertently Omitted, the matter will be determined by expedited arbitration. All newly created (after 9/15/11) characters and other Creative Elements that first appear in a work that is titled or branded with “Spider-Man” or in which “Spider-Man” is the main protagonist (but not including any team- up work featuring both Spider-Man and another major Marvel character that isn’t part of the Spider-Man Property). The origin story, secret identities, alter egos, powers, costumes, equipment, and other elements of, or associated with, Spider-Man and the other Creative Elements covered above. The story lines of individual Marvel comic books and other works in which Spider-Man or other characters granted to SPE appear, subject to Marvel confirming ownership. -

A White-Cheeked Crested Gibbon Ethogram & a Comparison Between Siamang

A white-cheeked crested gibbon ethogram & A comparison between siamang (Symphalangus syndactylus) and white-cheeked crested gibbon (Nomascus leucogenys) Janet de Vries Juli – November 2004 The gibbon research Lab., Zürich (Zwitserland) Van Hall Instituut, Leeuwarden J. de Vries: Ethogram of the White-Cheeked Crested Gibbon 2 A white-cheeked crested gibbon ethogram A comparison between siamang (Symphalangus syndactylus) and white-cheeked crested gibbon (Nomascus leucogenys) By: Janet de Vries Final project Animal management Projectnumber: 344311 Juli 2004 – November 2004-12-01 Van Hall Institute Supervisor: Thomas Geissmann of the Gibbon Research Lab Supervisors: Marcella Dobbelaar, & Celine Verheijen of Van Hall Institute Keywords: White-cheeked crested gibbon (Nomascus leucogenys), Siamang (Symphalangus syndactylus), ethogram, behaviour elements. J. de Vries: Ethogram of the White-Cheeked Crested Gibbon 3 Preface This project… text missing Janet de Vries Leeuwarden, November 2004 J. de Vries: Ethogram of the White-Cheeked Crested Gibbon 4 Contents Summary ................................................................................................................................ 5 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 6 1.1 Gibbon Ethograms ..................................................................................................... 6 1.2 Goal ..........................................................................................................................