Submitted by Denis Keegan BA

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Myth, Metatext, Continuity and Cataclysm in Dc Comics’ Crisis on Infinite Earths

WORLDS WILL LIVE, WORLDS WILL DIE: MYTH, METATEXT, CONTINUITY AND CATACLYSM IN DC COMICS’ CRISIS ON INFINITE EARTHS Adam C. Murdough A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2006 Committee: Angela Nelson, Advisor Marilyn Motz Jeremy Wallach ii ABSTRACT Angela Nelson, Advisor In 1985-86, DC Comics launched an extensive campaign to revamp and revise its most important superhero characters for a new era. In many cases, this involved streamlining, retouching, or completely overhauling the characters’ fictional back-stories, while similarly renovating the shared fictional context in which their adventures take place, “the DC Universe.” To accomplish this act of revisionist history, DC resorted to a text-based performative gesture, Crisis on Infinite Earths. This thesis analyzes the impact of this singular text and the phenomena it inspired on the comic-book industry and the DC Comics fan community. The first chapter explains the nature and importance of the convention of “continuity” (i.e., intertextual diegetic storytelling, unfolding progressively over time) in superhero comics, identifying superhero fans’ attachment to continuity as a source of reading pleasure and cultural expressivity as the key factor informing the creation of the Crisis on Infinite Earths text. The second chapter consists of an eschatological reading of the text itself, in which it is argued that Crisis on Infinite Earths combines self-reflexive metafiction with the ideologically inflected symbolic language of apocalypse myth to provide DC Comics fans with a textual "rite of transition," to win their acceptance for DC’s mid-1980s project of self- rehistoricization and renewal. -

Arctic Exploration and the Explorers of the Past

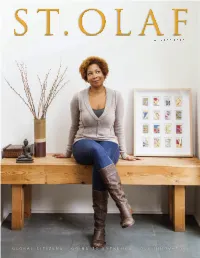

st.olafWiNtEr 2013 GLOBAL CITIZENS GOING TO EXTREMES OLE INNOVATORS ON ThE COvER: Vanessa trice Peter ’93 in the Los Angeles studio of paper artist Anna Bondoc. PHOtO By nAnCy PAStOr / POLAriS ST. OLAF MAGAzINE WINTER 2013 volume 60 · No. 1 Carole Leigh Engblom eDitOr Don Bratland ’87, holmes Design Art DireCtOr Laura hamilton Waxman COPy eDitOr Suzy Frisch, Joel hoekstra ’92, Marla hill holt ’88, Erin Peterson, Jeff Sauve, Kyle Schut ’13 COntriButinG writerS Fred J. Field, Stuart Isett, Jessica Brandi Lifl and, Mike Ludwig ’01, Kyle Obermann ’14, Nancy Pastor, Tom Roster, Chris Welsch, Steven Wett ’15 COntriButinG PHOtOGrA PHerS st. olaf Magazine is published three times annually (winter, Spring, Fall) by St. Olaf College, with editorial offi ces at the Offi ce of Marketing and Com- 16 munications, 507-786-3032; email: [email protected] 7 postmaster: Send address changes to Data Services, St. Olaf College, 1520 St. Olaf Ave., Northfi eld, MN 55057 readers may update infor- mation online: stolaf.edu/alumni or email alum-offi [email protected]. Contact the Offi ce of Alumni and Parent relations, 507- 786-3028 or 888-865-6537 52 Class Notes deadlines: Spring issue: Feb. 1 Fall issue: June 1 winter issue: Oct. 1 the content for class notes originates with the Offi ce of Alumni and Parent relations and is submitted to st. olaf Magazine, which reserves the right to edit for clarity and space constraints. Please note that due to privacy concerns, inclusion is at the discretion of the editor. www.stolaf.edu st.olaf features Global Citizens 7 By MArLA HiLL HOLt ’88 St. -

Copyright 2013 Shawn Patrick Gilmore

Copyright 2013 Shawn Patrick Gilmore THE INVENTION OF THE GRAPHIC NOVEL: UNDERGROUND COMIX AND CORPORATE AESTHETICS BY SHAWN PATRICK GILMORE DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2013 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Michael Rothberg, Chair Professor Cary Nelson Associate Professor James Hansen Associate Professor Stephanie Foote ii Abstract This dissertation explores what I term the invention of the graphic novel, or more specifically, the process by which stories told in comics (or graphic narratives) form became longer, more complex, concerned with deeper themes and symbolism, and formally more coherent, ultimately requiring a new publication format, which came to be known as the graphic novel. This format was invented in fits and starts throughout the twentieth century, and I argue throughout this dissertation that only by examining the nuances of the publishing history of twentieth-century comics can we fully understand the process by which the graphic novel emerged. In particular, I show that previous studies of the history of comics tend to focus on one of two broad genealogies: 1) corporate, commercially-oriented, typically superhero-focused comic books, produced by teams of artists; 2) individually-produced, counter-cultural, typically autobiographical underground comix and their subsequent progeny. In this dissertation, I bring these two genealogies together, demonstrating that we can only truly understand the evolution of comics toward the graphic novel format by considering the movement of artists between these two camps and the works that they produced along the way. -

Universidade De São Paulo Escola De Comunicação E Artes Programa De Pós-Graduação Em Ciências Da Comunicação O Discurs

UNIVERSIDADE DE SÃO PAULO ESCOLA DE COMUNICAÇÃO E ARTES PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM CIÊNCIAS DA COMUNICAÇÃO O DISCURSO AUTOBIOGRÁFICO NOS QUADRINHOS: UMA ARQUEOLOGIA DO EU NA OBRA DE ROBERT CRUMB E ANGELI Juscelino Neco de Souza Júnior São Paulo, Dezembro de 2014 2 UNIVERSIDADE DE SÃO PAULO ESCOLA DE COMUNICAÇÃO E ARTES PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM CIÊNCIAS DA COMUNICAÇÃO O discurso autobiográfico no quadrinhos: uma arqueologia do eu na obra de Robert Crumb e Angeli Juscelino Neco de Souza Júnior Tese apresentada à Escola de Comunicação em Artes da Universidade de São Paulo, para a obtenção do título de Doutor em Ciências da Comunicação, Área Temática Interfaces Sociais da Comunicação, sob orientação do Prof. Dr. Waldomiro de Castro Santos Vergueiro. São Paulo, Dezembro de 2014 3 Banca Examinadora: Nome do autor: _______________________________________________________ Título da Tese: ________________________________________________________ Presidente da Banca: Prof. Dr. ____________________________________________ Banca Examinadora: Prof. Dr. __________________________________ Instituição: _________________ Prof. Dr. __________________________________ Instituição: _________________ Prof. Dr. __________________________________ Instituição: _________________ Prof. Dr. __________________________________ Instituição: _________________ Prof. Dr. __________________________________ Instituição: _________________ Aprovada em: _____ / _____ / _____ 4 Comics are words and pictures. You can do anything with words and pictures. Harvey Pekar 5 Pra -

Zatanna and the House of Secrets Graphic Novels for Kids & Teens 741.5 Dc’S New Youth Movement Spring 2020 - No

MEANWHILE ZATANNA AND THE HOUSE OF SECRETS GRAPHIC NOVELS FOR KIDS & TEENS 741.5 DC’S NEW YOUTH MOVEMENT SPRING 2020 - NO. 40 PLUS...KIRBY AND KURTZMAN Moa Romanova Romanova Caspar Wijngaard’s Mary Saf- ro’s Ben Pass- more’s Pass- more David Lapham Masters Rick Marron Burchett Greg Rucka. Pat Morisi Morisi Kieron Gillen The Comics & Graphic Novel Bulletin of satirical than the romantic visions of DC Comics is in peril. Again. The ever- Williamson and Wood. Harvey’s sci-fi struggling publisher has put its eggs in so stories often centered on an ordinary many baskets, from Grant Morrison to the shmoe caught up in extraordinary circum- “New 52” to the recent attempts to get hip with stances, from the titular tale of a science Brian Michael Bendis, there’s hardly a one left nerd and his musclehead brother to “The uncracked. The first time DC tried to hitch its Man Who Raced Time” to William of “The wagon to someone else’s star was the early Dimension Translator” (below). Other 1970s. Jack “the King” Kirby was largely re- tales involved arrogant know-it-alls who sponsible for the success of hated rival Marvel. learn they ain’t so smart after all. The star He was lured to join DC with promises of great- of “Television Terror”, the vicious despot er freedom and authority. Kirby was tired of in “The Radioactive Child” and the title being treated like a hired hand. He wanted to character of “Atom Bomb Thief” (right)— be the idea man, the boss who would come up with characters and concepts, then pass them all pay the price for their hubris. -

Customer Order Form

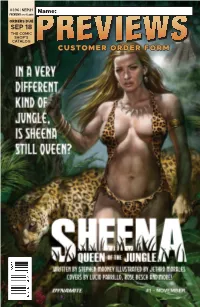

#396 | SEP21 PREVIEWS world.com Name: ORDERS DUE SEP 18 THE COMIC SHOP’S CATALOG PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CUSTOMER ORDER FORM Sep21 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 8/5/2021 10:52:51 AM GTM_Previews_ROF.indd 1 8/5/2021 8:54:18 AM PREMIER COMICS NEWBURN #1 IMAGE COMICS 34 A THING CALLED TRUTH #1 IMAGE COMICS 38 JOY OPERATIONS #1 DARK HORSE COMICS 84 HELLBOY: THE BONES OF GIANTS #1 DARK HORSE COMICS 86 SONIC THE HEDGEHOG: IMPOSTER SYNDROME #1 IDW PUBLISHING 114 SHEENA, QUEEN OF THE JUNGLE #1 DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT 132 POWER RANGERS UNIVERSE #1 BOOM! STUDIOS 184 HULK #1 MARVEL COMICS MP-4 Sep21 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 8/5/2021 10:52:11 AM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Guillem March’s Laura #1 l ABLAZE The Heathens #1 l AFTERSHOCK COMICS Fathom: The Core #1 l ASPEN COMICS Watch Dogs: Legion #1 l BEHEMOTH ENTERTAINMENT 1 Tuki Volume 1 GN l CARTOON BOOKS Mutiny Magazine #1 l FAIRSQUARE COMICS Lure HC l FANTAGRAPHICS BOOKS 1 The Overstreet Guide to Lost Universes SC/HC l GEMSTONE PUBLISHING Carbon & Silicon l MAGNETIC PRESS Petrograd TP l ONI PRESS Dreadnoughts: Breaking Ground TP l REBELLION / 2000AD Doctor Who: Empire of the Wolf #1 l TITAN COMICS Blade Runner 2029 #9 l TITAN COMICS The Man Who Shot Chris Kyle: An American Legend HC l TITAN COMICS Star Trek Explorer Magazine #1 l TITAN COMICS John Severin: Two-Fisted Comic Book Artist HC l TWOMORROWS PUBLISHING The Harbinger #2 l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT Lunar Room #1 l VAULT COMICS MANGA 2 My Hero Academia: Ultra Analysis Character Guide SC l VIZ MEDIA Aidalro Illustrations: Toilet-Bound Hanako Kun Ark Book SC l YEN PRESS Rent-A-(Really Shy!)-Girlfriend Volume 1 GN l KODANSHA COMICS Lupin III (Lupin The 3rd): Greatest Heists--The Classic Manga Collection HC l SEVEN SEAS ENTERTAINMENT APPAREL 2 Halloween: “Can’t Kill the Boogeyman” T-Shirt l HORROR Trese Vol. -

The Crusader Monthll,J Nelijsletter

THE CRUSADER MONTHLL,J NELIJSLETTER ROBERT F. WILLIAMS, EDITOR -IN EXILE- VoL . ~ - No. 9 MAY 1968 Afro-Americans & Slick John Kennedy Government of the United States is no government T~E of the Afro-Americans at all. The slick John Ken- nedy gang is operating one of the greatest sham govern- ment in the entire world. Afro-Americans and fair minded Od > ~- O THE wN«< /l~USL . lF Yov~Re EyER IN NE60, CALL ME AT whites must be gullible indeed to believe that the racist, KKK dominated so-called U.S. Government is concerned with the welfare and human rights of colored people. The colored people of the USA must bring themselves to realize that taken integration is a slick manuever to check the restlessness of an oppressed people fast becoming infect ed with the germ of total resistance policy developing among all of the oppressed peoples of the world. Token integration means nothing to the masses. Even an idiot should be able to see that so-called Token integration is no more than window dressing designed to lull the poor downtrodden Afro-American to sleep and to make the out side world think that the racist, savage USA is a fountainhead of social justice and democracy. The Afro-American in the USA is facing his greatest crisis since chattel slavery. All forms of violence and underhanded methods o.f extermination are being stepped up against our people. Contrary to what the "big daddies" and their "good nigras" would have us believe about all of the phoney progress they claim the race is making, the True status of the Afro-Ameri- can is s#eadily on the down turn. -

Aug CUSTOMER ORDER FORM

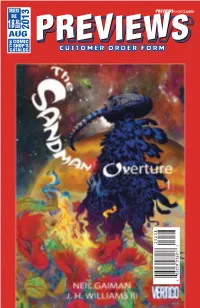

OrdErS PREVIEWS world.com duE th 18 aug 2013 aug COMIC THE SHOP’S PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CATALOG CUSTOMER ORDER FORM CUSTOMER 601 7 Aug13 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 7/3/2013 3:05:51 PM Available only DEADPOOL: “TACO ENTHUSIAST” from your local BLUE T-SHIRT comic shop! Preorder now! THE WALKING DEAD: STREET FIGHTER: DOCTOR WHO: “THE DIXON BROS.” “THE STREETS” “DON’T BLINK” GLOW ZIP HOODIE RED T-SHIRT IN THE DARK T-SHIRT Preorder now! Preorder now! Preorder now 8 Aug 13 COF Apparel Shirt Ad.indd 1 7/3/2013 10:34:19 AM PrETTY DEADLY #1 ImAgE COmICS THE SHAOLIN COWBOY #1 DArk HOrSE COmICS THE SANDmAN: OVErTUrE #1 DC COmICS / VErTIgO VELVET #1 ELFQUEST SPECIAL: ImAgE COmICS THE FINAL QUEST DArk HOrSE COmICS SAmUrAI JACk #1 IDW PUBLISHINg SUPErmAN/WONDEr mArVEL kNIgHTS: WOmAN #1 SPIDEr-mAN #1 DC COmICS mArVEL COmICS Aug13 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 7/3/2013 9:04:01 AM Featured Items COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS The Fox #1 l ARCHIE COMICS Uber Volume 1 Enhanced HC l AVATAR PRESS Imagine Agents #1 l BOOM! STUDIOS The Shadow Now #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Cryptozoic Man #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Peanuts Every Sunday 1952-1955 HC l FANTAGRAPHICS BOOKS Battling Boy GN/HC l :01 FIRST SECOND Letter 44 #1 l ONI PRESS 1 1 Ben 10 Omniverse Volume 1: Ghost Ship GN l PERFECT SQUARE X-O Manowar Deluxe HC l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT Miss Peregrine’s Home For Peculiar Children HC l YEN PRESS BOOKS The Superman Files HC l COMICS Doctor Who 50th Anniversary Anthology l DOCTOR WHO Doctor Who: The Vault: Treasures from the First 50 Years HC l DOCTOR WHO Dc Comics Guide To Creating Comics Sc l HOW-TO Star Trek: Mr. -

Australian & International Posters

Australian & International Posters Collectors’ List No. 200, 2020 e-catalogue Josef Lebovic Gallery 103a Anzac Parade (cnr Duke St) Kensington (Sydney) NSW p: (02) 9663 4848 e: [email protected] w: joseflebovicgallery.com CL200-1| |Paris 1867 [Inter JOSEF LEBOVIC GALLERY national Expo si tion],| 1867.| Celebrating 43 Years • Established 1977 Wood engra v ing, artist’s name Member: AA&ADA • A&NZAAB • IVPDA (USA) • AIPAD (USA) • IFPDA (USA) “Ch. Fich ot” and engra ver “M. Jackson” in image low er Address: 103a Anzac Parade, Kensington (Sydney), NSW portion, 42.5 x 120cm. Re- Postal: PO Box 93, Kensington NSW 2033, Australia paired miss ing por tions, tears Phone: +61 2 9663 4848 • Mobile: 0411 755 887 • ABN 15 800 737 094 and creases. Linen-backed.| Email: [email protected] • Website: joseflebovicgallery.com $1350| Text continues “Supplement to the |Illustrated London News,| July 6, 1867.” The International Exposition Hours: by appointment or by chance Wednesday to Saturday, 1 to 5pm. of 1867 was held in Paris from 1 April to 3 November; it was the second world’s fair, with the first being the Great Exhibition of 1851 in London. Forty-two (42) countries and 52,200 businesses were represented at the fair, which covered 68.7 hectares, and had 15,000,000 visitors. Ref: Wiki. COLLECTORS’ LIST No. 200, 2020 CL200-2| Alfred Choubrac (French, 1853–1902).| Jane Nancy,| c1890s.| Colour lithograph, signed in image centre Australian & International Posters right, 80.1 x 62.2cm. Repaired missing portions, tears and creases. Linen-backed.| $1650| Text continues “(Ateliers Choubrac. -

The Green Sheet and Opposition to American Motion Picture Classification in the 1960S

The Green Sheet and Opposition to American Motion Picture Classification in the 1960s By Zachary Saltz University of Kansas, Copyright 2011 Submitted to the graduate degree program in Film and Media Studies and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. John Tibbetts ________________________________ Dr. Michael Baskett ________________________________ Dr. Chuck Berg Date Defended: 19 April 2011 ii The Thesis Committee for Zachary Saltz certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: The Green Sheet and Opposition to American Motion Picture Classification in the 1960s ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. John Tibbetts Date approved: 19 April 2011 iii ABSTRACT The Green Sheet was a bulletin created by the Film Estimate Board of National Organizations, and featured the composite movie ratings of its ten member organizations, largely Protestant and represented by women. Between 1933 and 1969, the Green Sheet was offered as a service to civic, educational, and religious centers informing patrons which motion pictures contained potentially offensive and prurient content for younger viewers and families. When the Motion Picture Association of America began underwriting its costs of publication, the Green Sheet was used as a bartering device by the film industry to root out municipal censorship boards and legislative bills mandating state classification measures. The Green Sheet underscored tensions between film industry executives such as Eric Johnston and Jack Valenti, movie theater owners, politicians, and patrons demanding more integrity in monitoring changing film content in the rapidly progressive era of the 1960s. Using a system of symbolic advisory ratings, the Green Sheet set an early precedent for the age-based types of ratings the motion picture industry would adopt in its own rating system of 1968. -

Patrick Olliffe Interview & Demo Al Williamson the Man & His Work Remembered by Torres, Blevins, Schultz, Yeates, Ross, and Veitch

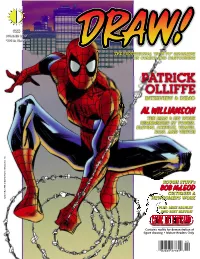

#23 SUMMER 2012 $7.95 In The US THE PROFESSIONAL “HOW-TO” MAGAZINE ON COMICS AND CARTOONING PATRICK OLLIFFE INTERVIEW & DEMO AL WILLIAMSON THE MAN & HIS WORK REMEMBERED BY TORRES, BLEVINS, SCHULTZ, YEATES, ROSS, AND VEITCH ROUGH STUFF’s BOB McLEOD CRITIQUES A Spider-Man TM Spider-Man & ©2012 Marvel Characters, Inc. NEWCOMER’S WORK PLUS: MIKE MANLEY AND BRET BLEVINS’ Contains nudity for demonstration of figure drawing • Mature Readers Only 0 2 1 82658 27764 2 THE PROFESSIONAL “HOW-TO” MAGAZINE ON COMICS & CARTOONING WWW.DRAW-MAGAZINE.BLOGSPOT.COM SUMMER 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS VOL. 1, NO. 23 Editor-in-Chief • Michael Manley Designer • Eric Nolen-Weathington PAT OLLIFFE Publisher • John Morrow Mike Manley interviews the artist about his career and working with Al Williamson Logo Design • John Costanza 3 Copy-Editing • Eric Nolen- Weathington Front Cover • Pat Olliffe DRAW! Summer 2012, Vol. 1, No. 23 was produced by Action Planet, Inc. and published by TwoMorrows Publishing. ROUGH CRITIQUE Michael Manley, Editor. John Morrow, Publisher. Bob McLeod gives practical advice and Editorial address: DRAW! Magazine, c/o Michael Manley, 430 Spruce Ave., Upper Darby, PA 19082. 22 tips on how to improve your work Subscription Address: TwoMorrows Publishing, 10407 Bedfordtown Dr., Raleigh, NC 27614. DRAW! and its logo are trademarks of Action Planet, Inc. All contributions herein are copyright 2012 by their respective contributors. Action Planet, Inc. and TwoMorrows Publishing accept no responsibility for unsolicited submissions. All artwork herein is copyright the year of produc- THE CRUSTY CRITIC tion, its creator (if work-for-hire, the entity which Jamar Nicholas reviews the tools of the trade. -

Collect10rs Digest

STO:RY PAPER COLLECT10RS DIGEST u.... /170 IIINS:: 1QQ-:;r; ""' 77 l..)Ulll- J..J'-'-" YUL I .J/ l'i 1U I '1 .JO Page 2 Good stocks of Nelson Lees, all series, including bound ones, quite a number of these (old series), selling cheap. Contents o . k . but amateurishl y bound~ Short runs . The nice half-years are in fine bindings . State wants . Bulk orders welcomed ~ Please suggest wants and approx . pr ice you wish to pa y . This applie s to all my stock . Pa y a visit to Aladdin's Cave ~ So much to see and you'll be most welcome . Please ring first~ Chuckles . Many half- year vols . of this beautif ul comic in colour . Others also such as Comic Cuts , Chips, Favorite, Merry & Bright, Funny Wonder, Jester, Comic Life , Butterfly & Firefly , Larks, Chicks Own, Tiny Tots, Tip Top , Micke y Mouse , etc . Thousands of single issues, pre and post war comics . You name it~ Boys' papers including the popular ones and some scarce title s too. WANTED: Monster Library , bound complete set (19) if possible. Early Magnets, pre 1931, good/ v. good only. All H . Baker Facsimiles and Book Club Specials in stock . Some s / hand . Please list wants of these lists free of new ones . Penny Dreadful s. Bound vols . Lots of everything , please keep in touch . No lists, sorry. NORMANSHAW 84 BELVEDERE ROAD LONDON, SE19 2HZ Nearest Station B .R. - Crystal Palace Phone 01 771 9857 STORY PAPER COLLECTOR COLLECTORS' DIGEST Founded in 1941 by Founded in 1946 by W. H. GANDER HERBERT LECKENBY Vol.