14. Frege on Sense and Reference (2)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

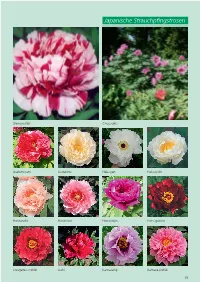

Japanische Strauchpfingstrosen

Japanische Strauchpfingstrosen Shimanishiki Chojuraku Asahiminato Godaishu Hakugan Hakuojishi Hanaasobi Hanakisoi Hanadaijin Hatsugarasu Jitsugetsu-nishiki Jushi Kamatafuji Kamata-nishiki 15 Kao Kokamon Kokuryu-nishiki Luo Yang Hong Meikoho Naniwa-nishiki Renkaku Rimpo Seidai Shim-daijin Shimano-fuji Shinfuso Shin-jitsugetsu Shinshifukujin Shiunden Taiyo Tamafuyo 16 Tamasudare Teni Yachiyotsubaki Yaezakura Yagumo Yatsukajishi Yoshinogawa High Noon Kinkaku Kinko Hakugan Kao 17 Europäische Strauchpfingstrosen Blanche de His Duchesse de Morny Isabelle Riviere Reine Elisabeth Chateau de Courson Jeanne d‘Arc Jacqueline Farvacques Zenobia 18 Rockii-Hybriden Souvenir de Lothar Parlasca Jin Jao Lou Ambrose Congrève Dojean E Lou Si Ezra Pound Fen He Guang Mang Si She Hai Tian E Hei Feng Die Hong Lian Hui He Ice Storm Katrin 19 Lan He Lydia Foote Rockii Ebert Schiewe Shu Sheng Peng Mo Souvenir de Ingo Schiewe Xue Hai Bing Xin Ye Guang Bei Zie Di Jin Feng deutscher Rockii-Sämling Lutea-, Delavayi- und Potaninii-Hybriden Anna Marie Terpsichore 20 Age of Gold Alhambra Alice in Wonderland Amber Moon Angelet Antigone Aphrodite Apricot Arcadia Argonaut Argosy Ariadne Artemis Banquet Black Douglas Black Panther Black Pirate Boreas Brocade Canary 21 Center Stage Chinese Dragon Chromatella Corsair Daedalus Damask Dare Devil Demetra Eldorado Flambeau Gauguin Gold Sovereign Golden Bowl Golden Era Golden Experience Golden Finch Golden Hind Golden Isle Golden Mandarin Golden Vanity 22 Happy Days Harvest Hélène Martin Helios Hephestos Hesperus Icarus Infanta Iphigenia Kronos L‘Espérance L‘Aurore La Lorraine Leda Madame Louis Henry Marchioness Marie Laurencin Mine d‘Or Mystery Narcissus 23 Nike Orion P. delavayi rot P. delavayi orange P. ludlowii P. lutea P. -

Reference and Sense

REFERENCE AND SENSE y two distinct ways of talking about the meaning of words y tlkitalking of SENSE=deali ng with relationshippggs inside language y talking of REFERENCE=dealing with reltilations hips bbtetween l. and the world y by means of reference a speaker indicates which things (including persons) are being talked about ege.g. My son is in the beech tree. II identifies persons identifies things y REFERENCE-relationship between the Enggplish expression ‘this p pgage’ and the thing you can hold between your finger and thumb (part of the world) y your left ear is the REFERENT of the phrase ‘your left ear’ while REFERENCE is the relationship between parts of a l. and things outside the l. y The same expression can be used to refer to different things- there are as many potential referents for the phrase ‘your left ear’ as there are pppeople in the world with left ears Many expressions can have VARIABLE REFERENCE y There are cases of expressions which in normal everyday conversation never refer to different things, i.e. which in most everyday situations that one can envisage have CONSTANT REFERENCE. y However, there is very little constancy of reference in l. Almost all of the fixing of reference comes from the context in which expressions are used. y Two different expressions can have the same referent class ica l example: ‘the MiMorning St’Star’ and ‘the Evening Star’ to refer to the planet Venus y SENSE of an expression is its place in a system of semantic relati onshi ps wit h other expressions in the l. -

The Meaning of Language

01:615:201 Introduction to Linguistic Theory Adam Szczegielniak The Meaning of Language Copyright in part: Cengage learning The Meaning of Language • When you know a language you know: • When a word is meaningful or meaningless, when a word has two meanings, when two words have the same meaning, and what words refer to (in the real world or imagination) • When a sentence is meaningful or meaningless, when a sentence has two meanings, when two sentences have the same meaning, and whether a sentence is true or false (the truth conditions of the sentence) • Semantics is the study of the meaning of morphemes, words, phrases, and sentences – Lexical semantics: the meaning of words and the relationships among words – Phrasal or sentential semantics: the meaning of syntactic units larger than one word Truth • Compositional semantics: formulating semantic rules that build the meaning of a sentence based on the meaning of the words and how they combine – Also known as truth-conditional semantics because the speaker’ s knowledge of truth conditions is central Truth • If you know the meaning of a sentence, you can determine under what conditions it is true or false – You don’ t need to know whether or not a sentence is true or false to understand it, so knowing the meaning of a sentence means knowing under what circumstances it would be true or false • Most sentences are true or false depending on the situation – But some sentences are always true (tautologies) – And some are always false (contradictions) Entailment and Related Notions • Entailment: one sentence entails another if whenever the first sentence is true the second one must be true also Jack swims beautifully. -

Two-Dimensionalism: Semantics and Metasemantics

Two-Dimensionalism: Semantics and Metasemantics YEUNG, \y,ang -C-hun ...:' . '",~ ... ~ .. A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Philosophy In Philosophy The Chinese University of Hong Kong January 2010 Abstract of thesis entitled: Two-Dimensionalism: Semantics and Metasemantics Submitted by YEUNG, Wang Chun for the degree of Master of Philosophy at the Chinese University of Hong Kong in July 2009 This ,thesis investigates problems surrounding the lively debate about how Kripke's examples of necessary a posteriori truths and contingent a priori truths should be explained. Two-dimensionalism is a recent development that offers a non-reductive analysis of such truths. The semantic interpretation of two-dimensionalism, proposed by Jackson and Chalmers, has certain 'descriptive' elements, which can be articulated in terms of the following three claims: (a) names and natural kind terms are reference-fixed by some associated properties, (b) these properties are known a priori by every competent speaker, and (c) these properties reflect the cognitive significance of sentences containing such terms. In this thesis, I argue against two arguments directed at such 'descriptive' elements, namely, The Argument from Ignorance and Error ('AlE'), and The Argument from Variability ('AV'). I thereby suggest that reference-fixing properties belong to the semantics of names and natural kind terms, and not to their metasemantics. Chapter 1 is a survey of some central notions related to the debate between descriptivism and direct reference theory, e.g. sense, reference, and rigidity. Chapter 2 outlines the two-dimensional approach and introduces the va~ieties of interpretations 11 of the two-dimensional framework. -

![Gottlob Frege: on Sense and Reference Professor Jeeloo Liu [Introduction]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5750/gottlob-frege-on-sense-and-reference-professor-jeeloo-liu-introduction-265750.webp)

Gottlob Frege: on Sense and Reference Professor Jeeloo Liu [Introduction]

Phil/Ling 375: Meaning and Mind [Handout #13] Gottlob Frege: On Sense and Reference Professor JeeLoo Liu [Introduction] I. Language and the World ___ How does language depict reality? Does reality have the same structure as the structure of language? For instance, the basic linguistic structure is a subject and a predicate, and the basic structure of the world is a particular and a universal (e.g. “Socrates is wise”). The subject usually is something of the world and we describe some property it has or does not have. A is F is true is A is really F, is false when A is not F. II. Different Elements of Language Singular terms: Terms that designate particular things Proper names Indexicals: now, today, here, I… Demonstratives: that, this… Pronouns (singular): he, she,… Definite descriptions (the so-and-so): Indefinite (singular) descriptions (a so-and-so) General terms: Terms that designate a kind of things or a certain property Mass nouns ___ natural kind terms (‘water,’ ‘tiger,’ ‘lemon’) ___ non-natural kind terms (‘bachelor’, ‘contract,’ ‘chair’) Adjectives (predicates): colors, shapes, etc. III. Traditional Theories of Meaning Prior to Frege [A] The Ideational Theory ___ The meaning of a linguistic expression is the speaker’s idea that is associated with the expression. [B] Mill’s Theory [the Object Theory] ___ The meaning of a singular term is the thing designated by that term; ___ the meaning of a name is just what the name stands for; the name does not have any other meaning e.g. ‘Socrates’ means Socrates e.g. ‘Dartmouth’ e.g. -

Tammuz Pan and Christ Otes on a Typical Case of Myth-Transference

TA MMU! PA N A N D C H R IST O TE S O N A T! PIC AL C AS E O F M! TH - TR ANS FE R E NC E AND DE VE L O PME NT B! WILFR E D H SC HO FF . TO G E THE R WIT H A BR IE F IL L USTR ATE D A R TIC L E O N “ PA N T H E R U STIC ” B! PAU L C AR US “ " ' u n wr a p n on m s on u cou n r , s n p r n u n n , 191 2 CHIC AGO THE O PE N CO URT PUBLISHING CO MPAN! 19 12 THE FA N F PRAXIT L U O E ES. a n t Fr ticpiccc o The O pen C ourt. TH E O PE N C O U RT A MO N TH L! MA GA! IN E Devoted to th e Sci en ce of Religion. th e Relig ion of Science. and t he Exten si on of th e Religi on Periiu nen t Idea . M R 1 12 . V XX . P 6 6 O L. VI o S T B ( N . E E E , 9 NO 7 Cepyricht by The O pen Court Publishing Gumm y, TA MM ! A A D HRI T U , P N N C S . NO TES O N A T! PIC AL C ASE O F M! TH-TRANSFERENC E AND L DEVE O PMENT. W D H H FF. -

Up for Discussion

A forum for members and member organizations to share ideas and concerns. Up for Discussion Send your comments by e-mail to <[email protected]>. both admire a sunset reflected on a lake of water. Is wa- The Use of IUPAC ter ‘water’ on Twin Earth? Is ‘water’ water to Oscar? We will return to this idea below when asking what the con- Names in Glossaries sequences would be of naming an incorrect structure by Doug Templeton that has become embedded in chemical science and in broader human experience. n a series of Glossaries related to terminology In his 1972 Princeton lectures [4], Saul Kripke elabo- in toxicology and published in Pure and Applied rates upon the concept of naming, and poses a thought IChemistry (see commentary [1]), common names experiment that can be referred to as “Is Schmidt of substances were used, accompanied to varying Gödel?”. Most of us may know little of Kurt Gödel, ex- degrees with the systematic IUPAC chemical name. In cept perhaps that he discovered the incompleteness of the most recent Glossary of Terms in Neurotoxicology arithmetic (I think I know what he looked like, because [2], however, it was mandated that all substances I have seen pictures, and I have read some biographi- referred to in the glossary should be accompanied, cal details, but I have no first hand knowledge of Gödel, at some point, by the IUPAC name. While use of and little opinion beyond a well-founded belief that he IUPAC names should be obligatory in original research discovered the incompleteness theorem). -

![Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8862/archons-commanders-notice-they-are-not-anlien-parasites-and-then-in-a-mirror-image-of-the-great-emanations-of-the-pleroma-hundreds-of-lesser-angels-438862.webp)

Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels

A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES WATCH THIS IMPORTANT VIDEO UFOs, Aliens, and the Question of Contact MUST-SEE THE OCCULT REASON FOR PSYCHOPATHY Organic Portals: Aliens and Psychopaths KNOWLEDGE THROUGH GNOSIS Boris Mouravieff - GNOSIS IN THE BEGINNING ...1 The Gnostic core belief was a strong dualism: that the world of matter was deadening and inferior to a remote nonphysical home, to which an interior divine spark in most humans aspired to return after death. This led them to an absorption with the Jewish creation myths in Genesis, which they obsessively reinterpreted to formulate allegorical explanations of how humans ended up trapped in the world of matter. The basic Gnostic story, which varied in details from teacher to teacher, was this: In the beginning there was an unknowable, immaterial, and invisible God, sometimes called the Father of All and sometimes by other names. “He” was neither male nor female, and was composed of an implicitly finite amount of a living nonphysical substance. Surrounding this God was a great empty region called the Pleroma (the fullness). Beyond the Pleroma lay empty space. The God acted to fill the Pleroma through a series of emanations, a squeezing off of small portions of his/its nonphysical energetic divine material. In most accounts there are thirty emanations in fifteen complementary pairs, each getting slightly less of the divine material and therefore being slightly weaker. The emanations are called Aeons (eternities) and are mostly named personifications in Greek of abstract ideas. -

Inalienable Possession in Swedish and Danish – a Diachronic Perspective 27

FOLIA SCANDINAVICA VOL. 23 POZNAŃ 20 17 DOI: 10.1515/fsp - 2017 - 000 5 INALIENABLE POSSESSI ON IN SWEDISH AND DANISH – A DIACHRONIC PERSP ECTIVE 1 A LICJA P IOTROWSKA D OMINIKA S KRZYPEK Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań A BSTRACT . In this paper we discuss the alienability splits in two Mainland Scandinavian language s, Swedish and Danish, in a diachronic context. Although it is not universally acknowledged that such splits exist in modern Scandinavian languages, many nouns typically included in inalienable structures such as kinship terms, body part nouns and nouns de scribing culturally important items show different behaviour from those considered alienable. The differences involve the use of (reflexive) possessive pronouns vs. the definite article, which differentiates the Scandinavian languages from e.g. English. As the definite article is a relatively new arrival in the Scandinavian languages, we look at when the modern pattern could have evolved by a close examination of possessive structures with potential inalienables in Old Swedish and Old Danish. Our results re veal that to begin with, inalienables are usually bare nouns and come to be marked with the definite article in the course of its grammaticalization. 1. INTRODUCTION One of the striking differences between the North Germanic languages Swedish and Danish on the one hand and English on the other is the possibility to use definite forms of nouns without a realized possessive in inalienable possession constructions. Consider the following examples: 1 The work on this paper was funded by the grant Diachrony of article systems in Scandi - navian languages , UMO - 2015/19/B/HS2/00143, from the National Science Centre, Poland. -

Epistemic Two-Dimensionalism and the Epistemic Argument

Epistemic two-dimensionalism and the epistemic argument Jeff Speaks November 12, 2008 Abstract. One of Kripke's fundamental objections to descriptivism was that the theory misclassifies certain a posteriori propositions expressed by sentences involving names as a priori. Though nowadays very few philosophers would endorse a descriptivism of the sort that Kripke criticized, many find two- dimensional semantics attractive as a kind of successor theory. Because two- dimensionalism needn't be a form of descriptivism, it is not open to the epis- temic argument as formulated by Kripke; but the most promising versions of two-dimensionalism are open to a close relative of that argument. One of Kripke's most powerful objections to the descriptivist theory of names he considered in Naming & Necessity was that the theory misclassifies the propositions expressed by certain sentences as a priori. For example, Kripke pointed out that the proposition expressed by a sentence of the form [1] If n exists, then n is F . will be, in the standard case, a posteriori. But according to the simplest version of descriptivism, the propositions expressed by sentences of the form of [1] just are the propositions expressed by the corresponding instances of [2] If the F exists, then the F is F . which seem clearly to be a priori truths. But even if many were convinced that Kripke's arguments discredited the descrip- tivist theories he considered, many were not satisfied by the Millian alternative to descriptivism. Many such philosophers take it to be a constraint on a theory of names that it capture the perceived explanatory advantages of descriptivism | including its account of the problems of empty names and of apparent substitution failures of coreferential names in attitude ascriptions | while avoiding Kripke's arguments against classical descriptivism. -

Heidi Savage April 2017 Kypris, Aphrodite, Venus, and Puzzles About Belief My Aim in This Paper Is to Show That the Existence Of

Heidi Savage April 2017 Kypris, Aphrodite, Venus, and Puzzles About Belief My aim in this paper is to show that the existence of empty names raise problems for the Millian that go beyond the traditional problems of accounting for their meanings. Specifically, they have implications for Millian strategies for dealing with puzzles about belief. The standard move of positing a referent for a mythical name to avoid the problem of meaning, because of its distinctly Millian motivation, implies that solving puzzles about belief, when they involve empty names, do in fact require reliance on Millianism after all. 1. Introduction The classic puzzle about belief involves a speaker who lacks knowledge of certain linguistic facts, specifically, knowledge that two distinct names refer to one and the same object -- that they are co-referential. Because of this lack of knowledge, it becomes possible for a speaker to maintain conflicting beliefs about the object in question. This becomes puzzling when we consider the idea that co-referential terms ought to be intersubstitutable in all contexts without any change in meaning. But belief puzzles show not only that this is false, but that it can actually lead to attributing contradictory beliefs to a speaker. The question, then, is what underlying assumption is causing the puzzle? The most frequent response has been to simply conclude that co-referentiality does not make for synonymy. And this conclusion, of course, rules out the Millian view of names – that the meaning of a name is its referent. Kripke, however, argues that belief puzzles are independent any particularly Millian assumptions. -

Frege's Theory of Sense

Frege’s theory of sense Jeff Speaks August 25, 2011 1. Three arguments that there must be more to meaning than reference ............................1 1.1. Frege’s puzzle about identity sentences 1.2. Understanding and knowledge of reference 1.3. Opaque contexts 2. The theoretical roles of senses .........................................................................................4 2.1. Frege’s criterion for distinctness of sense 2.2. Sense determines reference, but not the reverse 2.3. Indirect reference 2.4. Sense, force, and the theory of speech acts 3. What are senses? .............................................................................................................6 We have now seen how a theory of reference — a theory that assigns to each expression of the language a reference, which is what it contributes to determining the truth or falsity of sentences in which it occurs — might look for a fragment of English. (The fragment of English includes proper names, n-place predicates, and quantifiers.) We now turn to Frege’s reasons for thinking that a theory of reference must be supplemented with a theory of sense. 1. THREE ARGUMENTS THAT THERE MUST BE MORE TO MEANING THAN REFERENCE 1.1. Frege’s puzzle about identity sentences As Frege says at the outset of “On sense and reference,” identity “gives rise to challenging questions which are not altogether easy to answer.” The puzzle raised by identity sentences is that, if, even though “the morning star” and “the evening star” have the same reference — the planet Venus — the sentences [1] The morning star is the morning star. [2] The morning star is the evening star. seem quite different. They seem, as Frege says, to differ in “cognitive value.” [1] is trivial and a priori; whereas [2] seems a posteriori, and could express a valuable extension of knowledge — it, unlike [1], seems to express an astronomical discovery which took substantial empirical work to make.