Zoological Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Role of Exposure in Conservation

Behavioral Application in Wildlife Photography: Developing a Foundation in Ecological and Behavioral Characteristics of the Zanzibar Red Colobus Monkey (Procolobus kirkii) as it Applies to the Development Exhibition Photography Matthew Jorgensen April 29, 2009 SIT: Zanzibar – Coastal Ecology and Natural Resource Management Spring 2009 Advisor: Kim Howell – UDSM Academic Director: Helen Peeks Table of Contents Acknowledgements – 3 Abstract – 4 Introduction – 4-15 • 4 - The Role of Exposure in Conservation • 5 - The Zanzibar Red Colobus (Piliocolobus kirkii) as a Conservation Symbol • 6 - Colobine Physiology and Natural History • 8 - Colobine Behavior • 8 - Physical Display (Visual Communication) • 11 - Vocal Communication • 13 - Olfactory and Tactile Communication • 14 - The Importance of Behavioral Knowledge Study Area - 15 Methodology - 15 Results - 16 Discussion – 17-30 • 17 - Success of the Exhibition • 18 - Individual Image Assessment • 28 - Final Exhibition Assessment • 29 - Behavioral Foundation and Photography Conclusion - 30 Evaluation - 31 Bibliography - 32 Appendices - 33 2 To all those who helped me along the way, I am forever in your debt. To Helen Peeks and Said Hamad Omar for a semester of advice, and for trying to make my dreams possible (despite the insurmountable odds). Ali Ali Mwinyi, for making my planning at Jozani as simple as possible, I thank you. I would like to thank Bi Ashura, for getting me settled at Jozani and ensuring my comfort during studies. Finally, I am thankful to the rangers and staff of Jozani for welcoming me into the park, for their encouragement and support of my project. To Kim Howell, for agreeing to support a project outside his area of expertise, I am eternally grateful. -

World's Most Endangered Primates

Primates in Peril The World’s 25 Most Endangered Primates 2016–2018 Edited by Christoph Schwitzer, Russell A. Mittermeier, Anthony B. Rylands, Federica Chiozza, Elizabeth A. Williamson, Elizabeth J. Macfie, Janette Wallis and Alison Cotton Illustrations by Stephen D. Nash IUCN SSC Primate Specialist Group (PSG) International Primatological Society (IPS) Conservation International (CI) Bristol Zoological Society (BZS) Published by: IUCN SSC Primate Specialist Group (PSG), International Primatological Society (IPS), Conservation International (CI), Bristol Zoological Society (BZS) Copyright: ©2017 Conservation International All rights reserved. No part of this report may be reproduced in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the publisher. Inquiries to the publisher should be directed to the following address: Russell A. Mittermeier, Chair, IUCN SSC Primate Specialist Group, Conservation International, 2011 Crystal Drive, Suite 500, Arlington, VA 22202, USA. Citation (report): Schwitzer, C., Mittermeier, R.A., Rylands, A.B., Chiozza, F., Williamson, E.A., Macfie, E.J., Wallis, J. and Cotton, A. (eds.). 2017. Primates in Peril: The World’s 25 Most Endangered Primates 2016–2018. IUCN SSC Primate Specialist Group (PSG), International Primatological Society (IPS), Conservation International (CI), and Bristol Zoological Society, Arlington, VA. 99 pp. Citation (species): Salmona, J., Patel, E.R., Chikhi, L. and Banks, M.A. 2017. Propithecus perrieri (Lavauden, 1931). In: C. Schwitzer, R.A. Mittermeier, A.B. Rylands, F. Chiozza, E.A. Williamson, E.J. Macfie, J. Wallis and A. Cotton (eds.), Primates in Peril: The World’s 25 Most Endangered Primates 2016–2018, pp. 40-43. IUCN SSC Primate Specialist Group (PSG), International Primatological Society (IPS), Conservation International (CI), and Bristol Zoological Society, Arlington, VA. -

Common Chimpanzees (Pan Troglodytes), Moun

KroeberAnthropological Society Papers, Nos. 71-72, 1990 Colobine Socioecology and Female-bonded Models of Primate Social Structure Craig B. Stanford Ecological models ofprimate social systems have been used extensively to explain the variationsfound in social organization among living primates and to accountforprimate sociality itself. Recent attempts to characterize primate social systems as either 'female-bonded" or "non-female-bonded" establish a typology that does notfully consider the variation inpatterns ofsex-biased dispersal seen in the Primate order. Thispaper uses as its example the Old World monkey subfamily Colobinae to show that ecologi- cal models are basedprimarily onfrugivorous, territorialpinmates. The models are inadequate to explain patterns ofintergroup competition and should not be usedfor setting general rulesforprimate societies. Apreliminary alternative view ofsex-biased dispersal that is basedonfrequency dependence is offered. INTRODUCTION bonded according to each species' typical pattern Trivers (1972) and Emlen and Oring (1977) of sex-biased dispersal. Males are assumed to outlined the hypothesis that females and males have a greater lifetime reproductive potential than have been selected to invest their lifetime energies females, and in most species they invest less in differently: females in maintaining access to offspring than do females (Trivers 1972). Since maintenance and growth resources, in order to food intake for an individual female primate is invest most in their offspring; and males in a maximized by feeding singly, the evolution of reproductive strategy that maximizes access to fe- primate sociality suggests that there is some bene- males, investing relatively little in offspring. In fit accruing to females who forage as a group. short, females should compete for food, and Wrangham (1980) considered this benefit, which males should compete for females. -

Semnopithecus Entellus) in the ARAVALLI HILLS of RAJASTHAN, INDIA

Contents TIGERPAPER Population Ecology of Hanuman Langurs in the Aravalli Hills of Rajasthan, India.................................................................. 1 Status and Conservation of Gangetic Dolphin in the Karnali River, Nepal........................................................................... 8 Population Estimation of Tigers in Maharashtra............................. 11 Use of Capped Langur Habitat Suitability Analysis in Planning And Management of Upland Protected Areas in Bangladesh......... 13 Eco-Friendly Management of Rose-Ringed Parakeet in Winter Maize Crop................................................................. 23 The Wildlife Value: Example from West Papua, Indonesia.............. 27 The Butterfly Fauna of Visakhapatnam in South India.................... 30 FOREST NEWS What Were the Most Significant Developments in the Forestry Sector in Asia-Pacific in 2002?................................................. 1 Update on the Search for Excellence in Forest Management in Asia-Pacific.......................................................................... 6 Seeking New Highs for Mountain Area Development..................... 8 Adaptive Collaborative Management of Community Forests: An Option for Asia?................................................................ 8 Staff Movement........................................................................ 9 What’s the Role of Forests in Sustainable Water Management? 10 New RAP Forestry Publications.................................................. 12 -

Influence of Plant and Soil Chemistry on Food Selection, Ranging Patterns, and Biomass of Colobus Guereza in Kakamega Forest, Ke

International Journal of Primatology, Vol. 28, No. 3, June 2007 (C 2007) DOI: 10.1007/s10764-006-9096-2 Influence of Plant and Soil Chemistry on Food Selection, Ranging Patterns, and Biomass of Colobus guereza in Kakamega Forest, Kenya Peter J. Fashing,1,2,3,7 Ellen S. Dierenfeld,4,5 and Christopher B. Mowry6 Received February 22, 2006; accepted May 26, 2006; Published Online May 24, 2007 Nutritional factors are among the most important influences on primate food choice. We examined the influence of macronutrients, minerals, and sec- ondary compounds on leaf choices by members of a foli-frugivorous popula- tion of eastern black-and-white colobus—or guerezas (Colobus guereza)— inhabiting the Kakamega Forest, Kenya. Macronutrients exerted a complex influence on guereza leaf choice at Kakamega. At a broad level, protein con- tent was the primary factor determining whether or not guerezas consumed specific leaf items, with eaten leaves at or above a protein threshold of ca. 14% dry matter. However, a finer grade analysis considering the selection ra- tios of only items eaten revealed that fiber played a much greater role than protein in influencing the rates at which different items were eaten relative to their abundance in the forest. Most minerals did not appear to influence leaf choice, though guerezas did exhibit strong selectivity for leaves rich in zinc. Guerezas avoided most leaves high in secondary compounds, though their top food item (Prunus africana mature leaves) contained some of the high- est condensed tannin concentrations of any leaves in their diet. Kakamega 1Department of Science and Conservation, Pittsburgh Zoo and PPG Aquarium, One Wild Place, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15206. -

Olive Colobus (Procolobus Verus) Call Combinations and Ecological

Journal of Entomology and Zoology Studies 2013; 1 (6): 15-21 ISSN 2320-7078 Olive colobus (Procolobus verus) call combinations and JEZS 2013; 1 (6): 15-21 ecological parameters in Taï National Park, Côte d’Ivoire © 2013 AkiNik Publications Received 24-10-2013 Accepted: 07-11-2013 Jean-Claude Koffi BENE, Eloi Anderson BITTY, Kouame Antoine Jean-Claude Koffi BENE N’GUESSAN UFR Environnement, Université Jean Lorougnon Guédé; BP 150 Abstract Daloa Animal communication is any transfer of information on the part of one or more animals that has an Email: [email protected] effect on the current or future behavior of another animal. The ability to communicate effectively with other individuals plays a critical role in the lives of all animals and uses several signals. Eloi Anderson BITTY Acoustic communication is exceedingly abundant in nature, likely because sound can be adapted to a Centre Suisse de Recherches wide variety of environmental conditions and behavioral situations. Olive colobus monkeys produce Scientifiques en Côte d’Ivoire; 01 BP a finite number of acoustically distinct calls as part of a species-specific vocal repertoire. The call 1303 Abidjan 01 system of Olive colobus is structurally more complex because calls are assembled into higher-order Email: [email protected] level of sequences that carry specific meanings. Focal animal studies and Ad Libitum conducted in three groups of Olive colobus monkeys in Taï National Park indicate that some environmental and Kouame Antoine N’GUESSAN social parameters significantly affect the emission of different call combination types of this monkey Centre Suisse de Recherches species. Scientifiques en Côte d’Ivoire; 01 BP 1303 Abidjan 01 Email: [email protected] Keywords: Olive colobus, call combination, social parameter, environment parameter. -

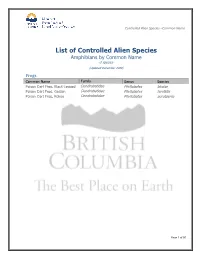

Controlled Alien Species -Common Name

Controlled Alien Species –Common Name List of Controlled Alien Species Amphibians by Common Name -3 species- (Updated December 2009) Frogs Common Name Family Genus Species Poison Dart Frog, Black-Legged Dendrobatidae Phyllobates bicolor Poison Dart Frog, Golden Dendrobatidae Phyllobates terribilis Poison Dart Frog, Kokoe Dendrobatidae Phyllobates aurotaenia Page 1 of 50 Controlled Alien Species –Common Name List of Controlled Alien Species Birds by Common Name -3 species- (Updated December 2009) Birds Common Name Family Genus Species Cassowary, Dwarf Cassuariidae Casuarius bennetti Cassowary, Northern Cassuariidae Casuarius unappendiculatus Cassowary, Southern Cassuariidae Casuarius casuarius Page 2 of 50 Controlled Alien Species –Common Name List of Controlled Alien Species Mammals by Common Name -437 species- (Updated March 2010) Common Name Family Genus Species Artiodactyla (Even-toed Ungulates) Bovines Buffalo, African Bovidae Syncerus caffer Gaur Bovidae Bos frontalis Girrafe Giraffe Giraffidae Giraffa camelopardalis Hippopotami Hippopotamus Hippopotamidae Hippopotamus amphibious Hippopotamus, Madagascan Pygmy Hippopotamidae Hexaprotodon liberiensis Carnivora Canidae (Dog-like) Coyote, Jackals & Wolves Coyote (not native to BC) Canidae Canis latrans Dingo Canidae Canis lupus Jackal, Black-Backed Canidae Canis mesomelas Jackal, Golden Canidae Canis aureus Jackal Side-Striped Canidae Canis adustus Wolf, Gray (not native to BC) Canidae Canis lupus Wolf, Maned Canidae Chrysocyon rachyurus Wolf, Red Canidae Canis rufus Wolf, Ethiopian -

Piliocolobus Semlikiensis, Semliki Red Colobus

The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ ISSN 2307-8235 (online) IUCN 2020: T92657343A92657454 Scope(s): Global Language: English Piliocolobus semlikiensis, Semliki Red Colobus Assessment by: Maisels, F. & Ting, N. View on www.iucnredlist.org Citation: Maisels, F. & Ting, N. 2020. Piliocolobus semlikiensis. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2020: e.T92657343A92657454. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020- 1.RLTS.T92657343A92657454.en Copyright: © 2020 International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale, reposting or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission from the copyright holder. For further details see Terms of Use. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ is produced and managed by the IUCN Global Species Programme, the IUCN Species Survival Commission (SSC) and The IUCN Red List Partnership. The IUCN Red List Partners are: Arizona State University; BirdLife International; Botanic Gardens Conservation International; Conservation International; NatureServe; Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew; Sapienza University of Rome; Texas A&M University; and Zoological Society of London. If you see any errors or have any questions or suggestions on what is shown in this document, please provide us with feedback so that we can correct or extend the information provided. THE IUCN RED LIST OF THREATENED SPECIES™ Taxonomy Kingdom Phylum Class Order Family Animalia Chordata Mammalia Primates Cercopithecidae Scientific Name: Piliocolobus semlikiensis (Colyn, 1991) Synonym(s): • Colobus ellioti Dollman, 1909 • Colobus variabilis Lorenz von Liburnau, 1914 • Colobus badius ssp. -

A Model of Colobus and Piliocolobus Behavioural Ecology: One Folivore

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Bournemouth University Research Online Korstjens & Dunbar Colobine model 1 2 Time constraints limit group sizes and distribution in red and black-and- 3 white colobus monkeys 4 5 6 Amanda H. Korstjens 7 R.I.M. Dunbar 8 9 10 British Academy Centenary Research Project 11 School of Biological Sciences 12 University of Liverpool 13 Crown St 14 Liverpool L69 7ZB 15 England 16 17 18 Email: [email protected] 19 20 21 22 23 Short title: Colobine model 24 Korstjens & Dunbar Colobine model 25 ABSTRACT 26 Several studies have shown that, in frugivorous primates, a major constraint on group size is 27 within-group feeding competition. This relationship is less obvious in folivorous primates. 28 We investigated whether colobine group sizes are constrained by time limitations as a result 29 of their low energy diet and ruminant-like digestive system. We used climate as an easy to 30 obtain proxy for the productivity of a habitat. Using the relationships between climate, group 31 size and time budget components observed for Colobus and Piliocolobus populations at 32 different research sites, we created two taxon-specific models. In both genera, feeding time 33 increased with group size (or biomass). The models for Colobus and Piliocolobus correctly 34 predicted the presence or absence of the genus at, respectively, 86% of 148 and 84% of 156 35 African primate sites. Median predicted group sizes where the respective genera were present 36 were 19 for Colobus and 53 for Piliocolobus. -

Phayre's Langur in Satchari National Park, Bangladesh

10 Asian Primates Journal 9(1), 2021 STATUS OF PHAYRE’S LANGUR Trachypithecus phayrei IN SATCHARI NATIONAL PARK, BANGLADESH Hassan Al-Razi1 and Habibon Naher2* Department of Zoology, Jagannath University, 9-11 Chittaranjan Avenue, Dhaka-1100, Bangladesh.1Email: chayan1999@ yahoo.com, 2Email: [email protected]. *Corresponding author ABSTRACT We studied the population status of Phayre’s Langur in Satchari National Park, Bangladesh, and threats to this population, from January to December 2016. We recorded 23 individuals in three groups. Group size ranged from four to 12 (mean 7.7±4.0) individuals; all groups contained a single adult male, 1–4 females and 2–7 immature individuals (subadults, juveniles and infants). Habitat encroachment for expansion of lemon orchards by the Tipra ethnic community and habitat degradation due to logging and firewood collection are the main threats to the primates. Road mortality, electrocution and tourist activities were additional causes of stress and mortality. Participatory work and awareness programmes with the Tipra community or generation of alternative income sources may reduce the dependency of local people on forest resources. Strict implementation of the rules and regulations of the Bangladesh Wildlife (Security and Conservation) Act 2012 can limit habitat encroachment and illegal logging, which should help in the conservation of this species. Key Words: Group composition, habitat encroachment, Satchari National Park. INTRODUCTION Phayre’s Langur (Phayre’s Leaf Monkey, Spectacled (1986) recorded 15 Phayre’s Langur groups comprising Langur) Trachypithecus phayrei (Blyth) occurs in 205 individuals in the north-east and south-east of Bangladesh, China, India and Myanmar (Bleisch et al., Bangladesh. -

Refuting the Validity of Golden-Crowned Langur Presbytis Johnaspinalli Nardelli 2015 (Mammalia, Primates, Cercopithecidae)

Zoosyst. Evol. 97 (1) 2021, 141–145 | DOI 10.3897/zse.97.62235 No longer based on photographs alone: refuting the validity of golden-crowned langur Presbytis johnaspinalli Nardelli 2015 (Mammalia, Primates, Cercopithecidae) Vincent Nijman1 1 Oxford Wildlife Trade Research Group, School of Social Sciences and Centre for Functional Genomics, Department of Biological and Medical Sciences, Oxford Brookes University, Gipsy Lane, Oxford, OX3 0BP, UK http://zoobank.org/2C3A7C82-A9BE-4FD1-A21D-113EC28C0224 Corresponding author: Vincent Nijman ([email protected]) Academic editor: M.T.R. Hawkins ♦ Received 18 December 2020 ♦ Accepted 19 January 2021 ♦ Published 11 February 2021 Abstract Increasingly, new species are being described without there being a name-bearing type specimen. In 2015, a new species of primate was described, the golden-crowned langur Presbytis johnaspinalli Nardelli, 2015 on the basis of five photographs that were posted on the Internet in 2009. After publication, the validity of the species was questioned as it was suggested that the animals were par- tially and selectively bleached ebony langurs Trachypithecus auratus (É. Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, 1812). Since the whereabouts of the animals were unknown, it was difficult to see how this matter could be resolved and the current taxonomic status of P. johnaspinalli remains unclear. I present new information about the fate of the individual animals in the photographs and their species identifica- tion. In 2009, thirteen of the langurs on which Nardelli based his description were brought to a rescue centre where, after about three months, they regained their normal black colouration confirming the bleaching hypothesis. Eight of the langurs were released in a forest and two were monitored for two months in 2014. -

OPTIMAL FORAGING on the ROOF of the WORLD: a FIELD STUDY of HIMALAYAN LANGURS a Dissertation Submitted to Kent State University

OPTIMAL FORAGING ON THE ROOF OF THE WORLD: A FIELD STUDY OF HIMALAYAN LANGURS A dissertation submitted to Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Kenneth A. Sayers May 2008 Dissertation written by Kenneth A. Sayers B.A., Anderson University, 1996 M.A., Kent State University, 1999 Ph.D., Kent State University, 2008 Approved by ____________________________________, Dr. Marilyn A. Norconk Chair, Doctoral Dissertation Committee ____________________________________, Dr. C. Owen Lovejoy Member, Doctoral Dissertation Committee ____________________________________, Dr. Richard S. Meindl Member, Doctoral Dissertation Committee ____________________________________, Dr. Charles R. Menzel Member, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Accepted by ____________________________________, Dr. Robert V. Dorman Director, School of Biomedical Sciences ____________________________________, Dr. John R. D. Stalvey Dean, College of Arts and Sciences ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES ............................................................................................... vi LIST OF TABLES ............................................................................................... viii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .....................................................................................x Chapter I. PRIMATES AT THE EXTREMES ..................................................1 Introduction: Primates in marginal habitats ......................................1 Prosimii .............................................................................................2