Central Dunedin Speed Restriction Health Impact Assessment Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Low Cost Food & Transport Maps

Low Cost Food & Transport Maps 1 Fruit & Vegetable Co-ops 2-3 Community Gardens 4 Community Orchards 5 Food Distribution Centres 6 Food Banks 7 Healthy Eating Services 8-9 Transport 10 Water Fountains 11 Food Foraging To view this information on an interactive map go to goo.gl/5LtUoN For further information contact Sophie Carty 03 477 1163 or [email protected] - INFORMATION UPDATED 10 / 2017 - WellSouth Primary Health Network HauoraW MatuaellSouth Ki Te Tonga Primary Health Network Hauora Matua Ki Te Tonga WellSouth Primary Health Network Hauora Matua Ki Te Tonga g f e h a c b d Fruit & Vegetable Co-ops All Saints' Fruit & Veges https://store.buckybox.com/all-saints-fruit-vege Low cost fruit and vegetables ST LUKE’S ANGLICAN CHURCH ALL SAINTS’ ANGLICAN CHURCH a 67 Gordon Rd, Mosgiel 9024 e 786 Cumberland St, North Dunedin 9016 OPEN: Thu 12pm - 1pm and 5pm - 6pm OPEN: Thu 8.45am - 10am and 4pm - 6pm ANGLICAN CHURCH ST MARTIN’S b 1 Howden Street, Green Island, Dunedin 9018, f 194 North Rd, North East Valley, Dunedin 9010 OPEN: Thu 9.30am - 11am OPEN: Thu 4.30pm - 6pm CAVERSHAM PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH ST THOMAS’ ANGLICAN CHURCH c Sidey Hall, 61 Thorn St, Caversham, Dunedin 9012, g 1 Raleigh St, Liberton, Dunedin 9010, OPEN: Thu 10am -11am and 5pm - 6pm OPEN: Thu 5pm - 6pm HOLY CROSS CHURCH HALL KAIKORAI PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH d (Entrance off Bellona St) St Kilda, South h 127 Taieri Road, Kaikorai, Dunedin 9010 Dunedin 9012 OPEN: Thu 4pm - 5.30pm OPEN: Thu 10.30am - 1pm * ORDER 1 WEEK IN ADVANCE WellSouth Primary Health Network Hauora Matua Ki Te Tonga 1 g h f a e Community Gardens Land gardened collectively with the opportunity to exchange labour for produce. -

Implementing Integrated Care 29 Aug 2017 Dunedin, New Zealand

Implementing Integrated Care 29 Aug 2017 Dunedin, New Zealand Symposium Report Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 1 Proceedings ................................................................................................................................... 1 Opening Remarks ...................................................................................................................... 1 Session 1: A Brief Introduction of CHeST .................................................................................... 2 Session 2: Keynote speakers ...................................................................................................... 4 Session 3: Panel discussion ........................................................................................................ 6 Closing remarks ......................................................................................................................... 6 Feedback ....................................................................................................................................... 7 Annex 1: Participants ..................................................................................................................... 8 Annex 2: Symposium Programme ................................................................................................ 12 Introduction The 1st annual symposium of The Centre for Health Systems and Technology -

Flood Hazard of Dunedin's Urban Streams

Flood hazard of Dunedin’s urban streams Review of Dunedin City District Plan: Natural Hazards Otago Regional Council Private Bag 1954, Dunedin 9054 70 Stafford Street, Dunedin 9016 Phone 03 474 0827 Fax 03 479 0015 Freephone 0800 474 082 www.orc.govt.nz © Copyright for this publication is held by the Otago Regional Council. This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part, provided the source is fully and clearly acknowledged. ISBN: 978-0-478-37680-7 Published June 2014 Prepared by: Michael Goldsmith, Manager Natural Hazards Jacob Williams, Natural Hazards Analyst Jean-Luc Payan, Investigations Engineer Hank Stocker (GeoSolve Ltd) Cover image: Lower reaches of the Water of Leith, May 1923 Flood hazard of Dunedin’s urban streams i Contents 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Overview ............................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Scope .................................................................................................................... 1 2. Describing the flood hazard of Dunedin’s urban streams .................................................. 4 2.1 Characteristics of flood events ............................................................................... 4 2.2 Floodplain mapping ............................................................................................... 4 2.3 Other hazards ...................................................................................................... -

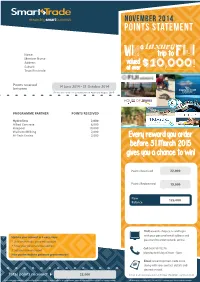

Points Statement

STstatement.pdf 7 10/11/14 2:27 pm NOVEMBER 2014 POINTS STATEMENT a luxury Name win trip to Fiji Member Name Address valued $10 000 Suburb at over , ! Town/Postcode Points received 14 June 2014 - 31 October 2014 between (Points allocated for spend between April and August 2014) FIJI’S CRUISE LINE PROGRAMME PARTNER POINTS RECEIVED Hydroflow 2,000 Allied Concrete 6,000 Hirepool 10,000 Waikato Milking 2,000 Hi-Tech Enviro 2,000 Every reward you order before 31 March 2015 gives you a chance to win! Points Received 22,000 Points Redeemed 15,000 New 125,000 Balance Visit rewards-shop.co.nz and login with your personal email address and Update your account in 3 easy steps: password to order rewards online. 1. Visit smart-trade .co.nz/my-account 2. Enter your personal email address Call 0800 99 76278 3. Set your new password Monday to Friday 8:30am - 5pm. Now you’re ready to get more great rewards! Email [email protected] along with your contact details and desired reward. * Total points received 22,000 Smart Trade International Ltd, PO Box 370, WMC, Hamilton 3240 *If your total points received does not add up, it may be a result of a reward cash top up, points transfer or manual points issue. Please call us if you have any queries. All information is correct as at 31 October 2014. Conditions apply. Go online for more details. GIVE YOUR POINTS A BOOST! Over 300 businesses offering Smart-Trade reward points. To earn points from any of the companies listed below, contact the business, express your desire to earn points and discuss opening an account. -

Community Emergency Response Guide Mosgiel-Taieri

Community Emergency Response Guide Mosgiel-Taieri 1 contents... Introduction 3 During a Landslide 20 After a Landslip 21 Mosgiel Map 4 Key Hazards 5 Pandemic 22 Flooding 5 Before a Pandemic 22 Fire / Wildfire 5 During a Pandemic 22 Earthquake 6 After a Pandemic 22 Major Storms / Snowstorms 6 Coping in Emergencies 23 Land Instability 7 What Would You Do? 24 Pandemic 7 Stuck at Home? 24 Can’t Get Home? 24 Floods 8 Before a Flood 8 Have to Evacuate? 25 During a Flood 8 No Power? 25 After a Flood 9 No Water? 26 Flood Maps 10 No Phone or Internet? 26 Caring for Pets and Livestock 27 Fire 12 Before a Fire 12 Emergency Planning 28 During a Fire 12 Step 1: Household Emergency Plan 28 After a Fire 13 Step 2: Emergency Kit 28 Step 3: Stay Connected 28 Earthquake 14 Before an Earthquake 14 Household Emergency Plan 29 During an Earthquake 14 Emergency Kit 32 After an Earthquake 15 Stay Connected 33 Local Dunedin Faults 16 Key Civil Defence Sites 34 Storms / Snowstorms 18 Before a Storm 18 Roles and Responsibilities 36 During a Storm 18 Community Response Group 37 After a Storm 19 Notes 38 Land Instability 20 Contact Information 39 Before a Landslide 20 2 introduction...Intro- Mosgiel and the Taieri Plain The Taieri Plain lies to the west of Dunedin and has a mix of rural and urban environs with Mosgiel being an important service town for the area’s rural community. There are several settlements across the Plain including the following: Henley is at the southern extremity of the City of Dunedin, 35 kilometres from the city centre, close to Lake Waihola, and at the confluence of the Taieri and Waipori Rivers. -

South Island Infrastructure Investment

South Island Infrastructure Investment • Rolling out more than $7 billion of investment in transport projects, schools, hospitals and water infrastructure across the South Island. • Commitment to rolling our shovel-ready projects and a pipeline of long-term projects to create certainty for our construction sector. Labour will continue to build on its strong record of investment in infrastructure and roll out more than $7 billion of infrastructure investment in the South Island. Our $7 billion of infrastructure investment in the South Island provides certainty to the regions and employers. This investment will result in long-term job creation and significant economic benefits. In government, we have managed the books wisely. With historically low interest rates, we are able to outline this much-needed investment in infrastructure. This investment is both affordable and the right thing to do. This will not be all of our infrastructure investment in the next term, and we will continue to invest in capital infrastructure for health, housing, transport and local government, as well as other areas. But this provides a pipeline of work that will assist us in recovering from the impacts of COVID-19. The overall infrastructure investment for the South Island includes: • $274.1 million of investment via the New Zealand Upgrade programme for transport projects • $368.72 million from the Provincial Growth Fund • $667 million from the IRG projects • $3.5 billion from the National Land Transport Programme (forecast 2018-2021). • $6 million from the -

The Dunedin Earthquake, 9 April, 1974 Part 2: Local

123 THE DUNEDIN EARTHQUAKE, 9 APRIL, 1974 PART 2: LOCAL EFFECTS D. G. Bishop* ABSTRACT The earthquake of 9 April, 1974 was the strongest experienced in the Dunedin area in historic times. It was centred at sea about 10 km south of the city and had a magnitude of 5.0. The felt intensity reached MMVII in the St. Clair area, where a ground acceleration of 0.27 g was recorded. Variations in felt intensity were determined from a survey of grocery stores. The intensity decreased rapidly away from a maximum on the alluvial ground of the southern suburbs and correlated strongly with the underlying rock type. The number of claims received by the Earthquake and War Damage Commission was extraordinarily large for an earthquake of this magnitude. Damage, generally of a rather minor nature, was reported from all parts of the city, but was greatly concentrated in the South Dunedin - St. Clair area. About half of the 3000 claims received included chimney damage. The effects of the earthquake highlight the need to assess the safety of public buildings in Dunedin, particularly those sited on areas of thick alluvium. INTRODUCTION central city area and an intensity of MMVII at St. Clair. A sharp earthquake was felt throughout the Dunedin City area at 7.50 p.m. on GEOLOGY Tuesday, 9 April, 1974. The earthquake had a shallow focus (probably about 20 km) Dunedin City is built on the southern about 10 km south of the city? its magnitude flank of the Dunedin Volcanic Complex was 5.0 (see Part 1 for details). -

Wellinformed May 2019

WellInformed May 2019 From the Chief Executive As I continue to travel the region, I am impressed with the desire of motivated people in primary care to deliver high quality care and be involved in new and improved models of service delivery. There is no better example than the rollout and implementation of the Health Care Home program in the Southern region which is showing very promising outcomes for practices and patients. Of note: • Three practices (16,475 patients) have opened doctors’ notes to patients. • 1,485 additional patients have been registered on portals in first tranche practices . • 35% of same day appointment requests have been resolved by phone, saving the patient from coming to the practice and giving the practice increased capacity. • Over 4,500 patients have had CLIC comprehensive health assessments. • A practice in Gore has successfully begun multi-disciplinary team meetings on Palliative and Level 3 CLIC patients. One of the key roles of an organisation such as WellSouth is to advocate for primary care and ensure that general practice has access to funding to support their enrolled patients. Primary Options for Acute Care (POAC) is one such example where funding has been found for the extended care that practices are able to undertake to keep their patients out of hospital. We will be working with practices to better understand what other services can be added to the list of POAC pathways. Again thank you to those that have invited me to their place of work. I have really enjoyed the visits and have learnt a lot. -

Māori Election Petitions of the 1870S: Microcosms of Dynamic Māori and Pākehā Political Forces

Māori Election Petitions of the 1870s: Microcosms of Dynamic Māori and Pākehā Political Forces PAERAU WARBRICK Abstract Māori election petitions to the 1876 Eastern Māori and the 1879 Northern Māori elections were high-stakes political manoeuvres. The outcomes of such challenges were significant in the weighting of political power in Wellington. This was a time in New Zealand politics well before the formation of political parties. Political alignments were defined by a mixture of individual charismatic men with a smattering of provincial sympathies and individual and group economic interests. Larger-than-life Māori and Pākehā political characters were involved in the election petitions, providing a window not only into the complex Māori political relationships involved, but also into the stormy Pākehā political world of the 1870s. And this is the great lesson about election petitions. They involve raw politics, with all the political theatre and power play, which have as much significance in today’s politics as they did in the past. Election petitions are much more than legal challenges to electoral races. There are personalities involved, and ideological stances between the contesting individuals and groups that back those individuals. Māori had to navigate both the Pākehā realm of central and provincial politics as well as the realm of Māori kin-group politics at the whānau, hapū and iwi levels of Māoridom. The political complexities of these 1870s Māori election petitions were but a microcosm of dynamic Māori and Pākehā political forces in New Zealand society at the time. At Waitetuna, not far from modern day Raglan in the Waikato area, the Māori meeting house was chosen as one of the many polling booths for the Western Māori electorate in the 1908 general election.1 At 10.30 a.m. -

Roll of Members of the New Zealand House of Representatives, 1854 Onwards

Roll of members of the New Zealand House of Representatives, 1854 onwards Sources: New Zealand Parliamentary Record, Newspapers, Political Party websites, New Zealand Gazette, New Zealand Parliamentary Debates (Hansard), Political Party Press Releases, Appendix to the Journal of the House of Representatives, E.9. Last updated: 17 November 2020 Abbreviations for the party affiliations are as follows: ACT ACT (Association of Consumers and Taxpayers) Lib. Liberal All. Alliance LibLab. Liberal Labour CD Christian Democrats Mana Mana Party Ch.H Christian Heritage ManaW. Mana Wahine Te Ira Tangata Party Co. Coalition Maori Maori Party Con. Conservative MP Mauri Pacific CR Coalition Reform Na. National (1925 Liberals) CU Coalition United Nat. National Green Greens NatLib. National Liberal Party (1905) ILib. Independent Liberal NL New Labour ICLib. Independent Coalition Liberal NZD New Zealand Democrats Icon. Independent Conservative NZF New Zealand First ICP Independent Country Party NZL New Zealand Liberals ILab. Independent Labour PCP Progressive Coalition ILib. Independent Liberal PP Progressive Party (“Jim Anderton’s Progressives”) Ind. Independent R Reform IP. Independent Prohibition Ra. Ratana IPLL Independent Political Labour League ROC Right of Centre IR Independent Reform SC Social Credit IRat. Independent Ratana SD Social Democrat IU Independent United U United Lab. Labour UFNZ United Future New Zealand UNZ United New Zealand The end dates of tenure before 1984 are the date the House was dissolved, and the end dates after 1984 are the date of the election. (NB. There were no political parties as such before 1890) Name Electorate Parl’t Elected Vacated Reason Party ACLAND, Hugh John Dyke 1904-1981 Temuka 26-27 07.02.1942 04.11.1946 Defeated Nat. -

The New Zealand Gazette 1413

SEPT. 20] THE NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE 1413 Declaration of Result of Poll for the S01ithern 11! aori Electoral Disll'ict Patea : William Alfred Sheat. Petone : Michael Moohan. JOHN ROYDEN SANSOM, Returning Officer for the Southern Piako : William Stanley Goosman. I , Maori Electoral District, do hereby declare the result of the Ponsonby: Ritchie Macdonald. poll taken on the 1st day of September 1951 for the eleotion of a Raglan : Hallyburton Johns_tone. Member of Parliament for the said district to be as follows :- Rangitikei : Edward Brice Killen Gordon. Candidates. Votes Polled. Remuera : Ronald Macmillan Algie. Riccarton : Angus MoLagan. Eruera Tihema Tirikatene 979 William Kelly Beaton Rodney: Thomas Clifton Webb. 320 Roskill: John Rae. Total number of valid votes polled . I, 299 St Albans: Jack Thomas Watts. St. Kilda : James George Barnes. Number of votes rejeoted as informal 13 Selwyn: John Kenneth McAlpine. I therefore declare the said Eruera Tihema Tirikatene to be Sydenham: Mabel Bowden Howard. elected. Tamaki : Eric Henry Halstead. Tauranga: George Augustus Walsh. Dated at Christchurch, this 11th day of September 1951. Timaru: Clyde Leonard Carr. J. R. SANSOM, Returning Officer. Waikato: Geoffrey Fantham Sim. Waimarino : Patrick Kearins. Waimate: David Campbell Kidd. Wairarapa: Bertie Victor Cooksley. Dedaration of Result of Poll for the Western Maori Electoral, Dietrict Waitakere: Henry Greathead Rex Mason. Waitomo: Walter James Broadfoot. I JAMES ALEXANDER MILLS, Returning Officer for the Wallace : Thomas Lachlan Macdonald. 9 Western Maori Electoral District, do hereby declare the Wanganui: Joseph Bernard Francis Cotterill. result of the poll taken on the 1st day of September 1951" for the Wellington Central: Charles Henry Chapman. -

ONI Documents Indexed

ONI Documents Indexed HR ER Bruce 10,001 1866 501 1868 1,254 1871 534 1873 722 1874 723 1876 705 1879-1880 1,195 1884 1,388 1885 1,516 1887 1,463 HR ER Bruce Additional 87 1870 87 HR ER Bruce District 2,891 1869 34 1870 86 1872 727 1873 1,347 1875 697 HR ER Bruce Electorate 1,121 1878-1879 1,121 HR ER Bruce Objected List 39 1871 39 HR ER Bruce Suppl 178 1884 178 HR ER Bruce Supplement 31 1874 31 HR ER Bruce Supplementary 75 1885 32 1887 43 HR ER Caversham 8,878 1866 413 1869 527 1870 575 1872 740 1873 728 1874 609 1875 651 1876 1,731 1884 1,638 1887 1,266 HR ER Caversham District 2,272 1867 469 1868 525 1871 1,278 HR ER Caversham Electorate 3,066 1878 880 1879 977 1880 1,209 HR ER Caversham Objected List 48 1872 48 1 HR ER Caversham Supp 27 1869 27 HR ER Caversham Supplementary 280 1869 27 1887 253 HR ER Chalmers Electorate 4,341 1893 4,341 HR ER Chalmers Electorate 366 Supplementary 1893 366 HR ER Chalmers Electorate 184 Supplementary Roll No 2 1893 184 HR ER City of Dunedin 3,874 1879-1880 3,415 1880 459 HR ER City of Dunedin Electorate 24,208 0 1878 3,516 1879 3,749 1893 16,675 HR ER Clutha 7,718 1866 307 1868 438 1869 1,183 1870 487 1871 513 1872 466 1873 466 1875 1,005 1876 563 1884 909 1887 1,381 HR ER Clutha (Amended) 424 1871 424 HR ER Clutha District 331 1867 330 1875 1 HR ER Clutha Suppl No 1 188 1887 188 HR ER Clutha Supplement 31 1869 7 1874 24 HR ER Clutha Supplementary 82 1884 82 HR ER District of Dunstan 515 1871 515 HR ER District of Invercargill 464 1871 464 HR ER District of Oamaru 449 2 1871 449 HR ER District of Riverton