An Introduction to Some Historical Governmental Weather Records Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download the Major Players in the Potato Industry in China Report

Potential Opportunities for Potato Industry’s Development in China Based on Selected Companies Final Report March 2018 Submitted to: World Potato Congress, Inc. (WPC) Submitted by: CIP-China Center for Asia Pacific (CCCAP) Potential Opportunities for Potato Industry’s Development in China Based on Selected Companies Final Report March 2018 Huaiyu Wang School of Management and Economics, Beijing Institute of Technology 5 South Zhongguancun, Haidian District Beijing 100081, P.R. China [email protected] Junhong Qin Post-doctoral fellow Institute of Vegetables and Flowers Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences 12 Zhongguancun South Street Beijing 100081, P.R. China Ying Liu School of Management and Economics, Beijing Institute of Technology 5 South Zhongguancun, Haidian District Beijing 100081, P.R. China Xi Hu School of Management and Economics, Beijing Institute of Technology 5 South Zhongguancun, Haidian District Beijing 100081, P.R. China Alberto Maurer (*) Chief Scientist CIP-China Center for Asia Pacific (CCCAP) Room 709, Pan Pacific Plaza, A12 Zhongguancun South Street Beijing, P.R. China [email protected] (*) Corresponding author TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................... ii Introduction ................................................................................................................................................ 1 1. The Development of Potato Production in China ....................................................................... -

Research and Practice of Water Source Heat Pump Technology in Heyi Station

E3S Web of Conferences 218, 01004 (2020) https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202021801004 ISEESE 2020 Research and practice of water source heat pump technology in Heyi station Shiyao He 1, Yongxiang Ren 2, Kai Jiao 3, Jun Deng 4, Yiming Meng 5, Le Liu 6, Jinshuai Li 7, Renjie Li 8 1Engineering Technology Research Institute of Huabei Oilfield Company, Renqiu, Cangzhou,062552, China 2 Department of Technical Supervision and Inspection, Huabei Oilfield Company, Renqiu, Cangzhou,062552, P.R. China 3No.1 oil production plant of Huabei Oilfield Company, Renqiu, Cangzhou, 062552, China 4 No.3 oil production plant of Huabei Oilfield Company, Hejian, Cangzhou, 062552, China 5 No.3 oil production plant of Huabei Oilfield Company, Hejian, Cangzhou, 062552, China 6 No.1 oil production plant of Huabei Oilfield Company, Renqiu, Cangzhou, 062552, China 7Erlian branch of Huabei Oilfield Company,Xilin Gol League,Inner Mongolia, 011200,China 8 Engineering Technology Research Institute of Huabei Oilfield Company, Renqiu, Cangzhou, 062552, China Abstract. There are some problems in the thermal system of Huabei Oilfield, such as high energy consumption, high operation cost and poor production safety. With more stringent requirements for energy conservation and emission reduction,it is particularly important to replace fuel oil projects and improve the efficiency of heating system.The utilization of waste heat and waste heat resources in Huabei Oilfield and the application conditions of various heat pump technologies were investigated,according to the characteristics -

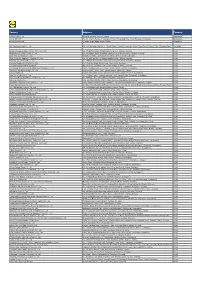

中国砂梨出口美国注册包装厂名单(20180825更新) Registered Packinghouses of Fresh Chinese Sand Pears to U.S

中国砂梨出口美国注册包装厂名单(20180825更新) Registered Packinghouses of Fresh Chinese Sand Pears to U.S. 序号 所在地 Location: County, 包装厂中文名 包装厂英文名 包装厂中文地址 包装厂英文地址 注册登记号 Number Location Province Chinese Name of Packing house English Name of Packing house Address in Chinese Address in English Registered Number 辛集市裕隆保鲜食品有限责任公 XINJI YULONG FRESH FOOD CO.,LTD. 1 河北辛集 XINJI,HEBEI 河北省辛集市南区朝阳路19号 NO.19 CHAOYANG ROAD,XINJI,HEBEI 1300GC001 司果品包装厂 PACKING HOUSE 2 河北辛集 XINJI,HEBEI 河北天华实业有限公司 HEBEI TIANHUA ENTERPRISE CO.,LTD. 河北省辛集市新垒头村 XINLEITOU VILLAGE,XINJI CITY, HEBEI 1300GC002 TONGDA ROAD, JINZHOU CITY,HEBEI 3 河北晋州 JINZHOU,HEBEI 晋州天洋贸易有限公司 JINZHOU TIANYANG TRADE CO.,LTD. 河北省晋州市通达路 1300GC005 PROVINCE HEBEI JINZHOU GREAT WALL ECONOMY 4 河北晋州 JINZHOU,HEBEI 河北省晋州市长城经贸有限公司 河北省晋州市马于开发区 MAYU,JINZHOU,HEBEI,CHINA 1300GC006 TRADE CO.,LTD. TIANJIAZHUANG INDUSTRIAL DEVELOPMENT 5 河北辛集 XINJI,HEBEI 辛集市天宇包装厂 XINJI TIANYU PACKING HOUSE 辛集市田家庄乡工业开发区 1300GC009 ZONE,XINJI,HEBEI HEBEI YUETAI AGRICULTURAL PRODUCTS TEXTILE INDUSTRIAL PARK,JINZHOU,HEBEI, 6 河北晋州 JINZHOU,HEBEI 河北悦泰农产品加工有限公司 河北省晋州市纺织园区 1300GC036 PROCESSING CO.,LTD. CHINA 7 河北泊头 BOTOU,HEBEI 泊头东方果品有限公司 BOTOU DONGFANG FRUIT CO.,LTD. 泊头河西金马小区 HEXI JINMA SMALL SECTION, BOTOU CITY 1306GC001 8 河北泊头 BOTOU,HEBEI 泊头亚丰果品有限公司 BOTOU YAFENG FRUIT CO., LTD. 泊头市齐桥镇 QIQIAO TOWN, BOTOU CITY 1306GC002 9 河北泊头 BOTOU,HEBEI 泊头食丰果品有限责任公司 BOTOU SHIFENG FRUIT CO., LTD. 泊头市齐桥镇大炉村 DALU VILLAGE,QIQIAO TOWN, BOTOU CITY 1306GC003 HEJIAN ZHONGHONG AGRICULTURE NANBALIPU VILLAGE, LONGHUADIAN TOWN, 10 河北河间 HEJIAN,HEBEI 河间市中鸿农产品有限公司 河间市龙华店乡南八里铺 1306GC005 PRODUCTS CO.,LTD. HEJIAN CITY 11 河北泊头 BOTOU,HEBEI 沧州金马果品有限公司 CANGZHOU JINMA FRUIT CO.,LTD. 泊头市龙华街 LONGHUA STREET,BOTOU CITY 1306GC018 SHEN VILLAGE, GUXIAN TOWN, QIXIAN, 12 山西晋中市 JINZHONG,SHANXI 祁县耀华果业有限公司 QIXIAN YAOHUA FRUIT CO., LTD 山西省晋中市祁县古县镇申村 1400GC020 JINZHONG, SHANXI 山西省晋中市祁县昭馀镇西关村西 SOUTHWESTERN ALLEY, XIGUAN VILLAGE, 13 山西晋中市 JINZHONG,SHANXI 祁县麒麟果业有限公司 QIXIAN QILIN FRUIT CO., LTD. -

Factory Address Country

Factory Address Country Durable Plastic Ltd. Mulgaon, Kaligonj, Gazipur, Dhaka Bangladesh Lhotse (BD) Ltd. Plot No. 60&61, Sector -3, Karnaphuli Export Processing Zone, North Potenga, Chittagong Bangladesh Bengal Plastics Ltd. Yearpur, Zirabo Bazar, Savar, Dhaka Bangladesh ASF Sporting Goods Co., Ltd. Km 38.5, National Road No. 3, Thlork Village, Chonrok Commune, Korng Pisey District, Konrrg Pisey, Kampong Speu Cambodia Ningbo Zhongyuan Alljoy Fishing Tackle Co., Ltd. No. 416 Binhai Road, Hangzhou Bay New Zone, Ningbo, Zhejiang China Ningbo Energy Power Tools Co., Ltd. No. 50 Dongbei Road, Dongqiao Industrial Zone, Haishu District, Ningbo, Zhejiang China Junhe Pumps Holding Co., Ltd. Wanzhong Villiage, Jishigang Town, Haishu District, Ningbo, Zhejiang China Skybest Electric Appliance (Suzhou) Co., Ltd. No. 18 Hua Hong Street, Suzhou Industrial Park, Suzhou, Jiangsu China Zhejiang Safun Industrial Co., Ltd. No. 7 Mingyuannan Road, Economic Development Zone, Yongkang, Zhejiang China Zhejiang Dingxin Arts&Crafts Co., Ltd. No. 21 Linxian Road, Baishuiyang Town, Linhai, Zhejiang China Zhejiang Natural Outdoor Goods Inc. Xiacao Village, Pingqiao Town, Tiantai County, Taizhou, Zhejiang China Guangdong Xinbao Electrical Appliances Holdings Co., Ltd. South Zhenghe Road, Leliu Town, Shunde District, Foshan, Guangdong China Yangzhou Juli Sports Articles Co., Ltd. Fudong Village, Xiaoji Town, Jiangdu District, Yangzhou, Jiangsu China Eyarn Lighting Ltd. Yaying Gang, Shixi Village, Shishan Town, Nanhai District, Foshan, Guangdong China Lipan Gift & Lighting Co., Ltd. No. 2 Guliao Road 3, Science Industrial Zone, Tangxia Town, Dongguan, Guangdong China Zhan Jiang Kang Nian Rubber Product Co., Ltd. No. 85 Middle Shen Chuan Road, Zhanjiang, Guangdong China Ansen Electronics Co. Ning Tau Administrative District, Qiao Tau Zhen, Dongguan, Guangdong China Changshu Tongrun Auto Accessory Co., Ltd. -

The Concealed Active Tectonics and Their Characteristics As Revealed by Drainage Density in the North China Plain (NCP)

____________________________________________________________________________www.paper.edu.cn Journal of Asian Earth Sciences 21 (2003) 989–998 www.elsevier.com/locate/jseaes The concealed active tectonics and their characteristics as revealed by drainage density in the North China plain (NCP) Zhujun Hana,*, Lun Wub, Yongkang Rana, Yanlin Yeb aInstitute of Geology, China Seismological Bureau, Beijing 100029, People’s Republic of China bDepartment of Geography, Peking University, Beijing 100871, People’s Republic of China Received 6 July 2001; revised 16 August 2002; accepted 9 October 2002 Abstract Drainage density, defined as river length per unit area, is an important tool to reveal the concealed active tectonics in the Quaternary- covered North China plain (NCP). The distribution of high-drainage density is characteristic of zonation and regionalisation. There are two sets of belts with high-drainage densities, which trend at 45–50 and 315–3208. The different locations and trends of these belts make it possible to divide the NCP into three regions. They are Beijing–Tianjin–Tangshan region in the north, Jizhong–Lubei region in the middle and Xingtai region in the south. Similarly located regions can be defined using contours of deformation data from geodetic-surveys from 1968 to 1982. Belts of high-drainage density are spatially coincident with seismotectonic zones and overlie concealed active faults. These active structures strike at an angle of <158 to that in the Eocene–Oligocene, a discordance, which may be an indication of an evolution of the fault pattern through time in the NCP during the Cenozoic. The current phase has more important consequences regarding seismic hazards in the NCP. -

Inter-Metropolitan Land-Price Characteristics and Patterns in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei Urban Agglomeration in China

sustainability Article Inter-Metropolitan Land-Price Characteristics and Patterns in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei Urban Agglomeration in China Can Li 1,2 , Yu Meng 1, Yingkui Li 3 , Jingfeng Ge 1,2,* and Chaoran Zhao 1 1 College of Resource and Environmental Science, Hebei Normal University, Shijiazhuang 050024, China 2 Hebei Key Laboratory of Environmental Change and Ecological Construction, Shijiazhuang 050024, China 3 Department of Geography, The University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN 37996, USA * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-0311-8078-7636 Received: 8 July 2019; Accepted: 25 August 2019; Published: 29 August 2019 Abstract: The continuous expansion of urban areas in China has increased cohesion and synergy among cities. As a result, the land price in an urban area is not only affected by the city’s own factors, but also by its interaction with nearby cities. Understanding the characteristics, types, and patterns of urban interaction is of critical importance in regulating the land market and promoting coordinated regional development. In this study, we integrated a gravity model with an improved Voronoi diagram model to investigate the gravitational characteristics, types of action, gravitational patterns, and problems of land market development in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei urban agglomeration region based on social, economic, transportation, and comprehensive land-price data from 2017. The results showed that the gravitational value of land prices for Beijing, Tianjin, Langfang, and Tangshan cities (11.24–63.35) is significantly higher than that for other cities (0–6.09). The gravitational structures are closely connected for cities around Beijing and Tianjin, but loosely connected for peripheral cities. -

A Possible Seismic Gap and High Earthquake Hazard in the North China Basin

A possible seismic gap and high earthquake hazard in the North China Basin An Yin1,2*, Xiangjiang Yu2,3, Z.-K. Shen2, and Jing Liu-Zeng4 1Structural Geology Group, China University of Geosciences (Beijing), Beijing 100083, China 2Department of Earth, Planetary, and Space Sciences, University of California–Los Angeles, Los Angeles, California 90095-1567, USA 3School of Earth and Space Sciences, Peking University, Beijing 100871, China 4Institute of Geology, China Earthquake Administration, Beijing 100027, China ABSTRACT indicated by a southward increase in eastward In this study we use combined historical records and results of early paleo-earthquake studies GPS velocities across the North China Basin to show that a 160 km seismic gap has existed along the northeast-striking right-slip Tangshan- (Fig. 2A) may have driven current right-slip Hejian-Cixian fault (China) over more than 8400 yr. The seismic gap is centered in Tianjin, a motion along northeast-striking faults via book- city in the North China Basin with a population of 11 million and located ~100 km from Bei- shelf faulting (Fig. 2B). jing, which has a population of 22 million. Current data indicate that the recurrence interval of major earthquakes along the Tangshan-Hejian-Cixian fault is 6700–10,800 yr. This implies SPATIOTEMPORAL PATTERNS OF that a large earthquake with an estimated magnitude of ~M 7.5 is either overdue or will occur SEISMIC RUPTURE within the next 2000–3000 yr along the inferred seismic gap if it is ruptured by a single event. Because of a general lack of surface ruptures Alternatively, the seismic gap may be explained by aseismic creeping, strain transfer between for most major historical earthquakes in the adjacent faults, or much longer recurrence times than the current knowledge indicates. -

Risen from Chaos: the Development of Modern Education in China, 1905-1948

The London School of Economics and Political Science Risen from Chaos: the development of modern education in China, 1905-1948 Pei Gao A thesis submitted to the Department of Economic History of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy London, March 2015 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 72182 words. I can confirm that my thesis was copy edited for conventions of language, spelling and grammar by Eve Richard. Abstract My PhD thesis studies the rise of modern education in China and its underlying driving forces from the turn of the 20th century. It is motivated by one sweeping educational movement in Chinese history: the traditional Confucius teaching came to an abrupt end, and was replaced by a modern and national education model at the turn of the 20th century. This thesis provides the first systematic quantitative studies that examine the rise of education through the initial stage of its development. -

Distribution, Genetic Diversity and Population Structure of Aegilops Tauschii Coss. in Major Whea

Supplementary materials Title: Distribution, Genetic Diversity and Population Structure of Aegilops tauschii Coss. in Major Wheat Growing Regions in China Table S1. The geographic locations of 192 Aegilops tauschii Coss. populations used in the genetic diversity analysis. Population Location code Qianyuan Village Kongzhongguo Town Yancheng County Luohe City 1 Henan Privince Guandao Village Houzhen Town Liantian County Weinan City Shaanxi 2 Province Bawang Village Gushi Town Linwei County Weinan City Shaanxi Prov- 3 ince Su Village Jinchengban Town Hancheng County Weinan City Shaanxi 4 Province Dongwu Village Wenkou Town Daiyue County Taian City Shandong 5 Privince Shiwu Village Liuwang Town Ningyang County Taian City Shandong 6 Privince Hongmiao Village Chengguan Town Renping County Liaocheng City 7 Shandong Province Xiwang Village Liangjia Town Henjin County Yuncheng City Shanxi 8 Province Xiqu Village Gujiao Town Xinjiang County Yuncheng City Shanxi 9 Province Shishi Village Ganting Town Hongtong County Linfen City Shanxi 10 Province 11 Xin Village Sansi Town Nanhe County Xingtai City Hebei Province Beichangbao Village Caohe Town Xushui County Baoding City Hebei 12 Province Nanguan Village Longyao Town Longyap County Xingtai City Hebei 13 Province Didi Village Longyao Town Longyao County Xingtai City Hebei Prov- 14 ince 15 Beixingzhuang Town Xingtai County Xingtai City Hebei Province Donghan Village Heyang Town Nanhe County Xingtai City Hebei Prov- 16 ince 17 Yan Village Luyi Town Guantao County Handan City Hebei Province Shanqiao Village Liucun Town Yaodu District Linfen City Shanxi Prov- 18 ince Sabxiaoying Village Huqiao Town Hui County Xingxiang City Henan 19 Province 20 Fanzhong Village Gaosi Town Xiangcheng City Henan Province Agriculture 2021, 11, 311. -

Contemporary Deformation and Earthquake Hazard of the Capital Circle of China Inferred from GPS Measurements

EGU21-4164 https://doi.org/10.5194/egusphere-egu21-4164 EGU General Assembly 2021 © Author(s) 2021. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Contemporary deformation and earthquake hazard of the Capital Circle of China inferred from GPS Measurements Shaogang Wei1,2, Xiwei Xu1, Tuo Shen1, and Xiaoqiong Lei1 1National Institute of Natural Hazards, Ministry of Emergency Management of China, Beijing, 100085, China 2The First Monitoring and Application Center, China Earthquake Administration, Tianjin, 300180, China The Capital Circle (CC) is a region with high risk of great damaging earthquake hazards. In our present study, by using a subset of rigorously GPS data around the North China Plain (NCP), med- small recent earthquakes data and focal mechanism of high earthquakes data covering its surrounding regions, the following major conclusions have been reached: (a) Driven by the deformation force associated with both eastward and westward motion, with respect to the NCP, of the rigid South China and the rigid Amurian block, widespread sinistral shear appear over the NCP, which results in clusters of parallel NNE-trending faults with predominant right-lateral strike- slips via bookshelf faulting within the interior of the NCP. (b) Fault plane solutions of recent earthquakes show that tectonic stress field in the NCP demonstrate overwhelming NE-ENE direction of the maximum horizontal principal stress, and that almost all great historical earthquakes in the NCP occurred along the NWW-trending Zhangjiakou-Bohai seismic belt and the NNE-trending Tangshan-Hejian-Cixian seismic belt. Additionally, We propose a simple conceptual model for inter-seismic deformation associated with the Capital Circle, which might suggest that two seismic gaps are located on the middle part of Tangshan-Hejian-Cixian fault seismic belt (Tianjin-Hejian segment) and the northeast part of Tanlu seismic belt (Anqiu segment), and constitute as, in our opinion, high risk areas prone to great earthquakes. -

Minimum Wage Standards in China August 11, 2020

Minimum Wage Standards in China August 11, 2020 Contents Heilongjiang ................................................................................................................................................. 3 Jilin ............................................................................................................................................................... 3 Liaoning ........................................................................................................................................................ 4 Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region ........................................................................................................... 7 Beijing......................................................................................................................................................... 10 Hebei ........................................................................................................................................................... 11 Henan .......................................................................................................................................................... 13 Shandong .................................................................................................................................................... 14 Shanxi ......................................................................................................................................................... 16 Shaanxi ...................................................................................................................................................... -

COUNTRY SECTION China Other Facility for the Collection Or Handling

Validity date from COUNTRY China 05/09/2020 00195 SECTION Other facility for the collection or handling of animal by-products (i.e. Date of publication unprocessed/untreated materials) 05/09/2020 List in force Approval number Name City Regions Activities Remark Date of request 00631765 Qixian Zengwei Mealworm Insect Breeding Cooperatives Qixian Shanxi CAT3 06/11/2014 Professional 0400ZC0003 SHIJIAZHUANG SHAN YOU CASHMERE PROCESSING Shijiazhuang Hebei CAT3 08/06/2020 CO.LTD. 0400ZC0004 HEBEI LIYIMENG CASHMERE PRODUCTS CO.LTD. Xingtai Hebei CAT3 08/06/2020 0400ZC0005 HEBEI VENICE CASHMERE TEXTILE CO.,LTD. Xingtai Hebei CAT3 08/06/2020 0400ZC0008 HEBEI HONGYE CASHMERE CO.,LTD. Xingtai Hebei CAT3 08/06/2020 0400ZC0009 HEBEI AOSHAWEI VILLUS PRODUCTS CO.,LTD Xingtai Hebei CAT3 08/06/2020 0400ZC0010 HEBEI JIAXING CASHMERE CO.,LTD Xingtai Hebei CAT3 26/05/2021 0400ZC0011 QINGHE COUNTY ZHENDA CASHMERE PRODUCTS CO., Xingtai Hebei CAT3 26/05/2021 LTD 0400ZC0012 HEBEI HUIXING CASHMERE GROUP CO.,LTD Xingtai Hebei CAT3 26/05/2021 0400ZC0014 ANPING JULONG ANIMAL BY PRODUCT CO.,LTD. Hengshui Hebei CAT3 08/06/2020 0400ZC0015 Anping XinXin Mane Co.,Ltd Hengshui Hebei CAT3 08/06/2020 0400ZC0016 ANPING COUNTY RISING STAR HAIR BRUSH Hengshui Hebei CAT3 08/06/2020 CORPORATION LIMITED 0400ZC0018 HENGSHUI PEACE FITNESS EQUIPMENT FACTORY Hengshui Hebei CAT3 08/06/2020 1 / 32 List in force Approval number Name City Regions Activities Remark Date of request 0400ZC0019 HEBEI XIHANG ANIMAL FURTHER DEVELOPMENT Hengshui Hebei CAT3 08/06/2020 CO.,LTD. 0400ZC0020 Anping Dual-horse Animal ByProducts Factory Hengshui Hebei CAT3 08/06/2020 0400ZC0021 HEBEI YUTENG CASHMERE PRODUCTS CO.,LTD.