Download the Hearing Transcript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Planning Board June 15, 2021 Page 1 Page 1 of 27 Meeting of The

Planning Board June 15, 2021 Page 1 Meeting of the Planning Board of the Town of Lewisboro held via the videoconferencing application Zoom (Meeting ID: 957 4529 2964). The audio recording of this meeting is Lewisboro Planning Board 06-15-21.mp3 and the YouTube link is https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bD5fYuufYoA (video starts at 2:11 of audio). Present: Janet Andersen, Chair Jerome Kerner Charlene Indelicato Greg La Sorsa Maureen Maguire Judson Siebert, Esq., Keane & Beane P.C., Planning Board Counsel Jan Johannessen, AICP, Kellard Sessions Consulting, Town Planner/Wetland Consultant Ciorsdan Conran, Planning Board Administrator Mary Shah, Conservation Advisory Council Approximately 14 participants were logged into the Zoom meeting and 2 viewers on YouTube. Ms. Andersen called the meeting to order at 7:30 p.m. Janet Andersen: Hi, I’m Janet Andersen and I’m calling to order the Town of Lewisboro Planning Board meeting for Tuesday, June 15, 2021, at 7:30 pm. This meeting is happening via Zoom, with live streaming to YouTube on the LewisboroTV channel and it's being recorded. The public can view the meeting via Zoom or YouTube, and we have confirmed that the feed is active and working, I think. Ciorsdan Conran: Almost working on YouTube. Janet Andersen: Almost up on YouTube. We will check that. In accordance with the governor's executive orders, no one is at our usual meeting location at 79 Bouton. Ciorsdan Conran, our planning board administrator, has confirmed that the meeting has been duly noticed and legal notice requirements have been fulfilled. Joining me on this Zoom conference from the town of Lewisboro are members of the planning board: Charlene Indelicato, Jerome Kerner, Greg La Sorsa, and Maureen Maguire. -

Songs of the Nativity

SONGS OF THE NATIVITY John Calvin Selected Sermons on Luke 1 & 2 Translated into English by ROBERT WHITE THE BANNER OF TRUTH TRUST 4 THE JUDGE OF ALL THE WORLD 'He has plucked princes from their seats, and has raised up the lowly. 53 He has filled with good things those who were hungry, and has left the rich empty. 54 He has received Israel his servant in remembrance of his mercy, 55 According as he spoke to our fathers, promising mercy to Abraham and his seedf or ever' (Luke r: 5 2- 5 5). t1 A ) e have seen already that, because God resists the proud, 'V V we cannot do better than walk before him in sincerity. For if we try to promote ourselves by high-fl.own ambition and careful scheming, God is bound to intervene and bring everything undone, so that it all ends in ruin and confusion. Let us not be too clever, but be sober-minded. If we did not live modestly, but rather aimed above our calling, we would become like wayward beasts-the faster we went, the more likely we would be to break our necks! That is why Mary continues her song with the words, 'God plucks princes and the mighty from their seats, and raises up the lowly.' Unbelievers, when they see the way the world is always chang• ing, think that God plays with humankind as with a ball. That is the kind of thing men say when they blaspheme God, or else they think that change is merely random.1 So what we have to notice is that, when God raises up the lowly and casts the mighty down, 49 SONGS OF THE NATIVITY The judge cf.A ll the World it is because men cannot endure their condition. -

PRAYER As It Was Meant to Be

PRAYER as it Was Meant to Be Will God answer? Will God hear me? When should I pray? How to lead public prayer? For what should I pray? Prayer As It Was Meant To Be by A. L. Parr © A. L. Parr, 2002 http://home.earthlink.net/~acptx Corinth Road Church of Christ 1155 Corinth Road Jacksonville, TX 75766 http://home.earthlink.net/~corinthroad Dedicated to Ed Brady & Edwin Davis elders who saw the timeliness of this study and encouraged the preparation of this study guide. Table of Contents Preface ................................................. 2 A SACRED PRIVILEGE ................................... 3 LEARNING FROM JESUS HOW TO PRAY (Part 1) ............. 5 LEARNING FROM JESUS HOW TO PRAY (Part 2) ............. 7 BEING QUALIFIED TO PRAY .............................. 9 ACCEPTABLE PRAYER (Part 1) ........................... 11 ACCEPTABLE PRAYER (Part 2) ........................... 13 ACCEPTABLE PRAYER (Part 3) ........................... 15 GOD ANSWERS PRAYER ................................ 18 THE CONFIDENCE THAT WE HAVE ...................... 20 LEADING PUBLIC PRAYER (Part 1) ....................... 21 LEADING PUBLIC PRAYER (Part 2) ....................... 23 PRAYER IS OFTEN THE UNUSED BLESSING ............... 25 CONCLUSION ......................................... 26 1 Preface In a country music song in the 1950's and 1960's a little boy, being tucked into bed by his father at the end of their day together, said, “Daddy, today you’ve taught me how to throw a ball, ride a bike and catch a fish; now will you teach me how to pray?” The father turned and left the room in tears because he had “forgotten how to pray.” New Christians often ask sincere questions about prayer. What is prayer? Should we pray to the Father or to Jesus? What do you visualize in your mind as you pray? What should we say in prayer? Why should we pray? These simple questions are basic to our being comfortable in our efforts to express our inner- most concerns to our Creator, Savior and Judge, and it is not only children and young Christians who want to know the answers. -

Closer to the Heart: an Exploration of Caring and Creative Visual Arts Classrooms

University of Denver Digital Commons @ DU Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 1-1-2010 Closer to the Heart: An Exploration of Caring and Creative Visual Arts Classrooms Juli B. Kramer University of Denver Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd Part of the Art Education Commons, Curriculum and Instruction Commons, and the Secondary Education Commons Recommended Citation Kramer, Juli B., "Closer to the Heart: An Exploration of Caring and Creative Visual Arts Classrooms" (2010). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 852. https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd/852 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. CLOSER TO THE HEART: AN EXPLORATION OF CARING AND CREATIVE VISUAL ARTS CLASSROOMS __________ A Dissertation Presented to the Morgridge College of Education University of Denver __________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy __________ by Juli B. Kramer June 2010 Advisor: P. Bruce Uhrmacher, Ph.D. ©Copyright by Juli B. Kramer 2010 All Rights Reserved Author: Juli B. Kramer Title: CLOSER TO THE HEART: AN EXPLORATION OF CARING AND CREATIVE VISUAL ARTS CLASSROOMS Advisor: P. Bruce Uhrmacher, Ph.D. Degree Date: June 2010 Abstract This study demonstrates how caring and creative secondary level visual arts classes facilitate the development of learning environments that enliven and expect the best of students; help them develop as autonomous and creative learners; provide them opportunities to care for others and the world around them; and keep them connected to their schools and education. -

(Pdf) Download

Artist Song 2 Unlimited Maximum Overdrive 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone 2Pac All Eyez On Me 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 3 Doors Down Behind Those Eyes 3 Doors Down Here By Me 3 Doors Down Live For Today 3 Doors Down Citizen Soldier 3 Doors Down Train 3 Doors Down Let Me Be Myself 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Be Like That 3 Doors Down The Road I'm On 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time (I Won't Go) 3 Doors Down Featuring Bob Seger Landing In London 38 Special If I'd Been The One 4him The Basics Of Life 98 Degrees Because Of You 98 Degrees This Gift 98 Degrees I Do (Cherish You) 98 Degrees Feat. Stevie Wonder True To Your Heart A Flock Of Seagulls The More You Live The More You Love A Flock Of Seagulls Wishing (If I Had A Photograph Of You) A Flock Of Seagulls I Ran (So Far Away) A Great Big World Say Something A Great Big World ft Chritina Aguilara Say Something A Great Big World ftg. Christina Aguilera Say Something A Taste Of Honey Boogie Oogie Oogie A.R. Rahman And The Pussycat Dolls Jai Ho Aaliyah Age Ain't Nothing But A Number Aaliyah I Can Be Aaliyah I Refuse Aaliyah Never No More Aaliyah Read Between The Lines Aaliyah What If Aaron Carter Oh Aaron Aaron Carter Aaron's Party (Come And Get It) Aaron Carter How I Beat Shaq Aaron Lines Love Changes Everything Aaron Neville Don't Take Away My Heaven Aaron Neville Everybody Plays The Fool Aaron Tippin Her Aaron Watson Outta Style ABC All Of My Heart ABC Poison Arrow Ad Libs The Boy From New York City Afroman Because I Got High Air -

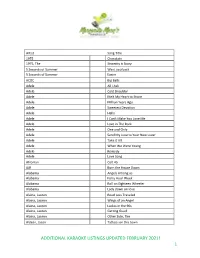

Additional Karaoke Listings Updated February 2021! 1

Artist Song Title 1975 Chocolate 1975, The Sincerity is Scary 5 Seconds of Summer Want you back 5 Seconds of Summer Easier ACDC Big Balls Adele All I Ask Adele Cold Shoulder Adele Melt My Heart to Stone Adele Million Years Ago Adele Sweetest Devotion Adele Hello Adele I Can't Make You Love Me Adele Love in The Dark Adele One and Only Adele Send My Love to Your New Lover Adele Take It All Adele When We Were Young Adele Remedy Adele Love Song Afroman Colt 45 AJR Burn the House Down Alabama Angels Among us Alabama Forty Hour Week Alabama Roll on Eighteen Wheeler Alabama Lady down on love Alaina, Lauren Road Less Traveled Alaina, Lauren Wings of an Angel Alaina, Lauren Ladies in the 90s Alaina, Lauren Getting Good Alaina, Lauren Other Side, The Aldean, Jason Tattoos on this town ADDITIONAL KARAOKE LISTINGS UPDATED FEBRUARY 2021! 1 Aldean, Jason Just Getting Started Aldean, Jason Lights Come On Aldean, Jason Little More Summertime, A Aldean, Jason This Plane Don't Go There Aldean, Jason Tonight Looks Good On You Aldean, Jason Gettin Warmed up Aldean, Jason Truth, The Aldean, Jason You make it easy Aldean, Jason Girl Like you Aldean, Jason Camouflage Hat Aldean, Jason We Back Aldean, Jason Rearview Town Aldean, Jason & Miranda Lambert Drowns The Whiskey Alice in Chains Man In The Box Alice in Chains No Excuses Alice in Chains Your Decision Alice in Chains Nutshell Alice in Chains Rooster Allan, Gary Every Storm (Runs Out of Rain) Allan, Gary Runaway Allen, Jimmie Best shot Anderson, John Swingin' Andress, Ingrid Lady Like Andress, Ingrid More Hearts Than Mine Angels and Airwaves Kiss & Tell Angston, Jon When it comes to loving you Animals, The Bring It On Home To Me Arctic Monkeys Do I Wanna Know Ariana Grande Breathin Arthur, James Say You Won't Let Go Arthur, James Naked Arthur, James Empty Space ADDITIONAL KARAOKE LISTINGS UPDATED FEBRUARY 2021! 2 Arthur, James Falling like the stars Arthur, James & Anne Marie Rewrite the Stars Arthur, James & Anne Marie Rewrite The Stars Ashanti Happy Ashanti Helpless (ft. -

Freecell and Other Stories

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses Summer 8-4-2011 FreeCell and Other Stories Susan Louvier University of New Orleans, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Part of the Other Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Louvier, Susan, "FreeCell and Other Stories" (2011). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 452. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/452 This Thesis-Restricted is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis-Restricted in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis-Restricted has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FreeCell and Other Stories A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in Film, Theatre and Communication Arts Creative Writing by Susan J. Louvier B.G.S. University of New Orleans 1992 August 2011 Table of Contents FreeCell .......................................................................................................................... 1 All of the Trimmings ..................................................................................................... 11 Me and Baby Sister ....................................................................................................... 29 Ivory Jupiter ................................................................................................................. -

English Song Booklet

English Song Booklet SONG NUMBER SONG TITLE SINGER SONG NUMBER SONG TITLE SINGER 100002 1 & 1 BEYONCE 100003 10 SECONDS JAZMINE SULLIVAN 100007 18 INCHES LAUREN ALAINA 100008 19 AND CRAZY BOMSHEL 100012 2 IN THE MORNING 100013 2 REASONS TREY SONGZ,TI 100014 2 UNLIMITED NO LIMIT 100015 2012 IT AIN'T THE END JAY SEAN,NICKI MINAJ 100017 2012PRADA ENGLISH DJ 100018 21 GUNS GREEN DAY 100019 21 QUESTIONS 5 CENT 100021 21ST CENTURY BREAKDOWN GREEN DAY 100022 21ST CENTURY GIRL WILLOW SMITH 100023 22 (ORIGINAL) TAYLOR SWIFT 100027 25 MINUTES 100028 2PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE 100030 3 WAY LADY GAGA 100031 365 DAYS ZZ WARD 100033 3AM MATCHBOX 2 100035 4 MINUTES MADONNA,JUSTIN TIMBERLAKE 100034 4 MINUTES(LIVE) MADONNA 100036 4 MY TOWN LIL WAYNE,DRAKE 100037 40 DAYS BLESSTHEFALL 100038 455 ROCKET KATHY MATTEA 100039 4EVER THE VERONICAS 100040 4H55 (REMIX) LYNDA TRANG DAI 100043 4TH OF JULY KELIS 100042 4TH OF JULY BRIAN MCKNIGHT 100041 4TH OF JULY FIREWORKS KELIS 100044 5 O'CLOCK T PAIN 100046 50 WAYS TO SAY GOODBYE TRAIN 100045 50 WAYS TO SAY GOODBYE TRAIN 100047 6 FOOT 7 FOOT LIL WAYNE 100048 7 DAYS CRAIG DAVID 100049 7 THINGS MILEY CYRUS 100050 9 PIECE RICK ROSS,LIL WAYNE 100051 93 MILLION MILES JASON MRAZ 100052 A BABY CHANGES EVERYTHING FAITH HILL 100053 A BEAUTIFUL LIE 3 SECONDS TO MARS 100054 A DIFFERENT CORNER GEORGE MICHAEL 100055 A DIFFERENT SIDE OF ME ALLSTAR WEEKEND 100056 A FACE LIKE THAT PET SHOP BOYS 100057 A HOLLY JOLLY CHRISTMAS LADY ANTEBELLUM 500164 A KIND OF HUSH HERMAN'S HERMITS 500165 A KISS IS A TERRIBLE THING (TO WASTE) MEAT LOAF 500166 A KISS TO BUILD A DREAM ON LOUIS ARMSTRONG 100058 A KISS WITH A FIST FLORENCE 100059 A LIGHT THAT NEVER COMES LINKIN PARK 500167 A LITTLE BIT LONGER JONAS BROTHERS 500168 A LITTLE BIT ME, A LITTLE BIT YOU THE MONKEES 500170 A LITTLE BIT MORE DR. -

“I Know That We the New Slaves”: an Illusion of Life Analysis of Kanye West’S Yeezus

1 “I KNOW THAT WE THE NEW SLAVES”: AN ILLUSION OF LIFE ANALYSIS OF KANYE WEST’S YEEZUS A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE MASTER OF ARTS BY MARGARET A. PARSON DR. KRISTEN MCCAULIFF - ADVISOR BALL STATE UNIVERSITY MUNCIE, INDIANA MAY 2017 2 ABSTRACT THESIS: “I Know That We the New Slaves”: An Illusion of Life Analysis of Kanye West’s Yeezus. STUDENT: Margaret Parson DEGREE: Master of Arts COLLEGE: College of Communication Information and Media DATE: May 2017 PAGES: 108 This work utilizes an Illusion of Life method, developed by Sellnow and Sellnow (2001) to analyze the 2013 album Yeezus by Kanye West. Through analyzing the lyrics of the album, several major arguments are made. First, Kanye West’s album Yeezus creates a new ethos to describe what it means to be a Black man in the United States. Additionally, West discusses race when looking at Black history as the foundation for this new ethos, through examples such as Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Nina Simone’s rhetoric, references to racist cartoons and movies, and discussion of historical events such as apartheid. West also depicts race through lyrics about the imagined Black male experience in terms of education and capitalism. Second, the score of the album is ultimately categorized and charted according to the structures proposed by Sellnow and Sellnow (2001). Ultimately, I argue that Yeezus presents several unique sounds and emotions, as well as perceptions on Black life in America. 3 Table of Contents Chapter One -

Songs by Title

16,341 (11-2020) (Title-Artist) Songs by Title 16,341 (11-2020) (Title-Artist) Title Artist Title Artist (I Wanna Be) Your Adams, Bryan (Medley) Little Ole Cuddy, Shawn Underwear Wine Drinker Me & (Medley) 70's Estefan, Gloria Welcome Home & 'Moment' (Part 3) Walk Right Back (Medley) Abba 2017 De Toppers, The (Medley) Maggie May Stewart, Rod (Medley) Are You Jackson, Alan & Hot Legs & Da Ya Washed In The Blood Think I'm Sexy & I'll Fly Away (Medley) Pure Love De Toppers, The (Medley) Beatles Darin, Bobby (Medley) Queen (Part De Toppers, The (Live Remix) 2) (Medley) Bohemian Queen (Medley) Rhythm Is Estefan, Gloria & Rhapsody & Killer Gonna Get You & 1- Miami Sound Queen & The March 2-3 Machine Of The Black Queen (Medley) Rick Astley De Toppers, The (Live) (Medley) Secrets Mud (Medley) Burning Survivor That You Keep & Cat Heart & Eye Of The Crept In & Tiger Feet Tiger (Down 3 (Medley) Stand By Wynette, Tammy Semitones) Your Man & D-I-V-O- (Medley) Charley English, Michael R-C-E Pride (Medley) Stars Stars On 45 (Medley) Elton John De Toppers, The Sisters (Andrews (Medley) Full Monty (Duets) Williams, Sisters) Robbie & Tom Jones (Medley) Tainted Pussycat Dolls (Medley) Generation Dalida Love + Where Did 78 (French) Our Love Go (Medley) George De Toppers, The (Medley) Teddy Bear Richard, Cliff Michael, Wham (Live) & Too Much (Medley) Give Me Benson, George (Medley) Trini Lopez De Toppers, The The Night & Never (Live) Give Up On A Good (Medley) We Love De Toppers, The Thing The 90 S (Medley) Gold & Only Spandau Ballet (Medley) Y.M.C.A. -

Kanye West Yeezus Clean Version Download Kanye West Yeezus Clean Version Download

kanye west yeezus clean version download Kanye west yeezus clean version download. Direct working Kanye West Yeezus Album Download Zip 2013. These are the immeasurably lofty stakes Kanye deals in on Yeezus, his sixth solo album. His intensity here has a heightened desperation as he howls into the void, but the Chicago native has always been beguiled by the view from above. The album is something of a razor-sharpened take on 2008's distressed 808s & Heartbreak and marks a blunt break with the filigreed maximalism Kanye so thoroughly nailed on My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy. For Kanye, there's purpose in repulsion. And on Yeezus, he trades out smooth soul and anthemic choruses for jarring electro, acid house, and industrial grind while delivering some of his most lewd and heart-crushing tales yet. This is willful provocation that Ice Cube, Madonna, and Trent Reznor could all beproud of. Referencing the sound of Yeezus in September 2013, West stated: "For me as Kanye West, I got to Bleep shit up. I'm going to take music and try to make it three dimensional. I'm not here to make easy listening, easily programmable music". Artist: Kanye West Album: Yeezus Year: 2013 Genre: Hip-Hop Quality: 320 kbps. Track list: 01. On Sight 02. Black Skinhead 03. I Am A God 04. New Slaves 05. Hold My Liquor 06. I’m In It 07. Blood On The Leaves 08. Guilt Trip 09. Send It Up 10. Bound 2. An Alternate Version Of Yeezus Exists -- But Will Kanye Release It? As producer Rick Rubin explains in his new song annotations for Genuis, Kanye West is both "careful and spontaneous" when he's creating music, which means that he usually creates several different options for one song before choosing the final version. -

Linda Davis to Matt King

Sound Extreme Entertainment Karaoke Show with Host 828-551-3519 [email protected] www.SoundExtreme.net In The Style Of Title Genre Linda Davis From The Inside Out Country Linda Davis I Took The Torch Out Of His Old Flame Country Linda Davis I Wanna Remember This Country Linda Davis I'm Yours Country Linda Ronstadt Blue Bayou Country & Pop Linda Ronstadt Different Drum Pop Linda Ronstadt Heartbeats Accelerating Country Linda Ronstadt How Do I Make You Pop Linda Ronstadt It's So Easy Country & Pop Linda Ronstadt I've Got A Crush On You Country & Pop Linda Ronstadt Love Is A Rose Country & Pop Linda Ronstadt Silver Threads & Golden Needles Country & Pop Linda Ronstadt That'll Be The Day Country & Pop Linda Ronstadt What's New Country & Pop Linda Ronstadt When Will I Be Loved Country & Pop Linda Ronstadt You're No Good Country & Pop Linda Ronstadt & Aaron Neville All My Life Pop / Rock Linda Ronstadt & Aaron Neville Don't Know Much Country & Pop Linda Ronstadt & Aaron Neville When Something Is Wrong With My Baby Pop Linda Ronstadt & James Ingram Somewhere Out There Pop / Rock Lindsay Lohan Over Pop Lindsay Lohan Rumors Pop / Rock Lindsey Haun Broken Country Lionel Cartwright Like Father Like Son Country Lionel Cartwright Miles & Years Country Lionel Richie All Night Long (All Night) Pop Lionel Richie Angel Pop Lionel Richie Dancing On The Ceiling Country & Pop Lionel Richie Deep River Woman Country & Pop Lionel Richie Do It To Me Pop / Rock Lionel Richie Hello Country & Pop Lionel Richie I Call It Love Pop Sound Extreme Entertainment www.SoundExtreme.net www.SoundExtremeWeddings.com www.CrocodileSmile.net 360 King Rd.