Closer to the Heart: an Exploration of Caring and Creative Visual Arts Classrooms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Planning Board June 15, 2021 Page 1 Page 1 of 27 Meeting of The

Planning Board June 15, 2021 Page 1 Meeting of the Planning Board of the Town of Lewisboro held via the videoconferencing application Zoom (Meeting ID: 957 4529 2964). The audio recording of this meeting is Lewisboro Planning Board 06-15-21.mp3 and the YouTube link is https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bD5fYuufYoA (video starts at 2:11 of audio). Present: Janet Andersen, Chair Jerome Kerner Charlene Indelicato Greg La Sorsa Maureen Maguire Judson Siebert, Esq., Keane & Beane P.C., Planning Board Counsel Jan Johannessen, AICP, Kellard Sessions Consulting, Town Planner/Wetland Consultant Ciorsdan Conran, Planning Board Administrator Mary Shah, Conservation Advisory Council Approximately 14 participants were logged into the Zoom meeting and 2 viewers on YouTube. Ms. Andersen called the meeting to order at 7:30 p.m. Janet Andersen: Hi, I’m Janet Andersen and I’m calling to order the Town of Lewisboro Planning Board meeting for Tuesday, June 15, 2021, at 7:30 pm. This meeting is happening via Zoom, with live streaming to YouTube on the LewisboroTV channel and it's being recorded. The public can view the meeting via Zoom or YouTube, and we have confirmed that the feed is active and working, I think. Ciorsdan Conran: Almost working on YouTube. Janet Andersen: Almost up on YouTube. We will check that. In accordance with the governor's executive orders, no one is at our usual meeting location at 79 Bouton. Ciorsdan Conran, our planning board administrator, has confirmed that the meeting has been duly noticed and legal notice requirements have been fulfilled. Joining me on this Zoom conference from the town of Lewisboro are members of the planning board: Charlene Indelicato, Jerome Kerner, Greg La Sorsa, and Maureen Maguire. -

(Pdf) Download

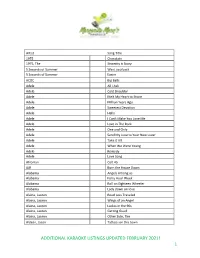

Artist Song 2 Unlimited Maximum Overdrive 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone 2Pac All Eyez On Me 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 3 Doors Down Behind Those Eyes 3 Doors Down Here By Me 3 Doors Down Live For Today 3 Doors Down Citizen Soldier 3 Doors Down Train 3 Doors Down Let Me Be Myself 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Be Like That 3 Doors Down The Road I'm On 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time (I Won't Go) 3 Doors Down Featuring Bob Seger Landing In London 38 Special If I'd Been The One 4him The Basics Of Life 98 Degrees Because Of You 98 Degrees This Gift 98 Degrees I Do (Cherish You) 98 Degrees Feat. Stevie Wonder True To Your Heart A Flock Of Seagulls The More You Live The More You Love A Flock Of Seagulls Wishing (If I Had A Photograph Of You) A Flock Of Seagulls I Ran (So Far Away) A Great Big World Say Something A Great Big World ft Chritina Aguilara Say Something A Great Big World ftg. Christina Aguilera Say Something A Taste Of Honey Boogie Oogie Oogie A.R. Rahman And The Pussycat Dolls Jai Ho Aaliyah Age Ain't Nothing But A Number Aaliyah I Can Be Aaliyah I Refuse Aaliyah Never No More Aaliyah Read Between The Lines Aaliyah What If Aaron Carter Oh Aaron Aaron Carter Aaron's Party (Come And Get It) Aaron Carter How I Beat Shaq Aaron Lines Love Changes Everything Aaron Neville Don't Take Away My Heaven Aaron Neville Everybody Plays The Fool Aaron Tippin Her Aaron Watson Outta Style ABC All Of My Heart ABC Poison Arrow Ad Libs The Boy From New York City Afroman Because I Got High Air -

Additional Karaoke Listings Updated February 2021! 1

Artist Song Title 1975 Chocolate 1975, The Sincerity is Scary 5 Seconds of Summer Want you back 5 Seconds of Summer Easier ACDC Big Balls Adele All I Ask Adele Cold Shoulder Adele Melt My Heart to Stone Adele Million Years Ago Adele Sweetest Devotion Adele Hello Adele I Can't Make You Love Me Adele Love in The Dark Adele One and Only Adele Send My Love to Your New Lover Adele Take It All Adele When We Were Young Adele Remedy Adele Love Song Afroman Colt 45 AJR Burn the House Down Alabama Angels Among us Alabama Forty Hour Week Alabama Roll on Eighteen Wheeler Alabama Lady down on love Alaina, Lauren Road Less Traveled Alaina, Lauren Wings of an Angel Alaina, Lauren Ladies in the 90s Alaina, Lauren Getting Good Alaina, Lauren Other Side, The Aldean, Jason Tattoos on this town ADDITIONAL KARAOKE LISTINGS UPDATED FEBRUARY 2021! 1 Aldean, Jason Just Getting Started Aldean, Jason Lights Come On Aldean, Jason Little More Summertime, A Aldean, Jason This Plane Don't Go There Aldean, Jason Tonight Looks Good On You Aldean, Jason Gettin Warmed up Aldean, Jason Truth, The Aldean, Jason You make it easy Aldean, Jason Girl Like you Aldean, Jason Camouflage Hat Aldean, Jason We Back Aldean, Jason Rearview Town Aldean, Jason & Miranda Lambert Drowns The Whiskey Alice in Chains Man In The Box Alice in Chains No Excuses Alice in Chains Your Decision Alice in Chains Nutshell Alice in Chains Rooster Allan, Gary Every Storm (Runs Out of Rain) Allan, Gary Runaway Allen, Jimmie Best shot Anderson, John Swingin' Andress, Ingrid Lady Like Andress, Ingrid More Hearts Than Mine Angels and Airwaves Kiss & Tell Angston, Jon When it comes to loving you Animals, The Bring It On Home To Me Arctic Monkeys Do I Wanna Know Ariana Grande Breathin Arthur, James Say You Won't Let Go Arthur, James Naked Arthur, James Empty Space ADDITIONAL KARAOKE LISTINGS UPDATED FEBRUARY 2021! 2 Arthur, James Falling like the stars Arthur, James & Anne Marie Rewrite the Stars Arthur, James & Anne Marie Rewrite The Stars Ashanti Happy Ashanti Helpless (ft. -

English Song Booklet

English Song Booklet SONG NUMBER SONG TITLE SINGER SONG NUMBER SONG TITLE SINGER 100002 1 & 1 BEYONCE 100003 10 SECONDS JAZMINE SULLIVAN 100007 18 INCHES LAUREN ALAINA 100008 19 AND CRAZY BOMSHEL 100012 2 IN THE MORNING 100013 2 REASONS TREY SONGZ,TI 100014 2 UNLIMITED NO LIMIT 100015 2012 IT AIN'T THE END JAY SEAN,NICKI MINAJ 100017 2012PRADA ENGLISH DJ 100018 21 GUNS GREEN DAY 100019 21 QUESTIONS 5 CENT 100021 21ST CENTURY BREAKDOWN GREEN DAY 100022 21ST CENTURY GIRL WILLOW SMITH 100023 22 (ORIGINAL) TAYLOR SWIFT 100027 25 MINUTES 100028 2PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE 100030 3 WAY LADY GAGA 100031 365 DAYS ZZ WARD 100033 3AM MATCHBOX 2 100035 4 MINUTES MADONNA,JUSTIN TIMBERLAKE 100034 4 MINUTES(LIVE) MADONNA 100036 4 MY TOWN LIL WAYNE,DRAKE 100037 40 DAYS BLESSTHEFALL 100038 455 ROCKET KATHY MATTEA 100039 4EVER THE VERONICAS 100040 4H55 (REMIX) LYNDA TRANG DAI 100043 4TH OF JULY KELIS 100042 4TH OF JULY BRIAN MCKNIGHT 100041 4TH OF JULY FIREWORKS KELIS 100044 5 O'CLOCK T PAIN 100046 50 WAYS TO SAY GOODBYE TRAIN 100045 50 WAYS TO SAY GOODBYE TRAIN 100047 6 FOOT 7 FOOT LIL WAYNE 100048 7 DAYS CRAIG DAVID 100049 7 THINGS MILEY CYRUS 100050 9 PIECE RICK ROSS,LIL WAYNE 100051 93 MILLION MILES JASON MRAZ 100052 A BABY CHANGES EVERYTHING FAITH HILL 100053 A BEAUTIFUL LIE 3 SECONDS TO MARS 100054 A DIFFERENT CORNER GEORGE MICHAEL 100055 A DIFFERENT SIDE OF ME ALLSTAR WEEKEND 100056 A FACE LIKE THAT PET SHOP BOYS 100057 A HOLLY JOLLY CHRISTMAS LADY ANTEBELLUM 500164 A KIND OF HUSH HERMAN'S HERMITS 500165 A KISS IS A TERRIBLE THING (TO WASTE) MEAT LOAF 500166 A KISS TO BUILD A DREAM ON LOUIS ARMSTRONG 100058 A KISS WITH A FIST FLORENCE 100059 A LIGHT THAT NEVER COMES LINKIN PARK 500167 A LITTLE BIT LONGER JONAS BROTHERS 500168 A LITTLE BIT ME, A LITTLE BIT YOU THE MONKEES 500170 A LITTLE BIT MORE DR. -

Cougar Chronicle: Spring 2017: Page 1

Cougar Chronicle: Spring 2017: Page 1 Cougar Chronicle: Spring 2017: Page 2 Cougar Credits Spring 2017 Each issue of the Cougar Chronicle, Carl Sandburg Middle School’s newspaper, has been conceptualized, developed, and created top to bottom by students in Grades 6-8. We are proud to bring you current events in our school community and are eager for you to read. Chronicle Crew Staff: Grade Students 6 Allison Altman, Malina Alwis, Sindhu Balakavi, Anthony Barge, Shreya Chintawar, Debosree Datta, Ryan Ferraro, Jasmine Foo, Isabella Florio, Jennasis Guth-Spitzer, Madison Hessler, Angelica Ho, Julie Khourshed, Ethan Kraja, Frederick Kusi, Jacob Nieves, Farah Omeed, Jenna Ortiz, Preston Peng, Gianna Porcelli, Jennifer Rojas, Ryan Santiago, Ameer Sheikh, Antonio Somma, Mikayla Stepper, Mariah Turpin, & Shaye Walker 7 Rishabh Jain, Isabelle Padilla, Felicia Padin, Samar Raju, Shilpi Shah, Carel Soney, Mason Stepper, & Avani Trivedi 8 Vaishnavi Adusumilli, Gina Battaglia, Carolena Lodzinski & William Tsang Advisor Mr. Burica Teachers: Interested in contributing an article? Students: Want to share an event, artwork, or writing? Please contact Mr. Burica at [email protected]. *Cover Artwork designed by Mason Stepper* Stories Prowling Inside: Cougar Chronicle: Spring 2017: Page 3 James & The PEER Day: 8th Grade Ellis Volleyball Giant Peach Jr. Island Trip: Tournament: Coverage: Pages 4-11 Pages 12-14 Pages 15-16 Page 17 World Down Autism ESL Spotlight: Podiatrist Syndrome Day: Awareness: Interview: Page 18 Page 19 Pages 20-21 Pages 22-23 Percy Jackson -

Music Psychotherapy with Refugee Survivors of Torture Interpretations of Three Clinical Case Studies

3TUDIA-USICA 3!-)!,!..% -USIC0SYCHOTHERAPY WITH2EFUGEE 3URVIVORSOF4ORTURE ).4%202%4!4)/.3/&4(2%%#,).)#!,#!3%345$)%3 Sami Alanne Music Psychotherapy with Refugee Survivors of Torture Interpretations of Three Clinical Case Studies Helsinki 2010 Music Education Department Studia Musica 44 Reprinted 2016 Copyright © Sami Alanne 2010 Cover design and layout by Gary Barlowsky Distributed throughout the world by Ostinato Oy Tykistönkatu 7 FIN-00260 HELSINKI FINLAND Tel: +358-(0)9- 443-116 Fax: +358-(0)9- 441- 305 www.ostinato.fi ISBN 978-952-5531-87-9 (paperback) ISBN 978-952-5531-88-6 (PDF) ISSN 0788-3757 Printed in Helsinki, Finland by Picaset Oy ABSTRACT Sami Alanne. 2010. Music Psychotherapy with Refugee Survivors of Torture. Interpretations of Three Clinical Case Studies. Sibelius Academy, Studia Musica 44. Music Education Department. Doctoral dissertation, 245 pages. The clinical data for this research were derived from three music psychotherapy cases of torture victims who in 2002 to 2004 lived as either asylum seekers or refugees in Finland. The patients were all traumatized men, originating from Central Africa, South Asia, and the Middle East, who received music therapy sessions as part of their rehabilitation. Music therapy was offered weekly or bi-monthly for the duration of one to two years. Music listening techniques, such as projective listening, guided imagery, and free association were applied in a psychoanalytic frame of reference. Data included 116 automatically audio recorded and transcribed therapy sessions, totalling over 100 hours of real time data that were both qualitatively and quantitatively analyzed by the researcher. While previous studies have examined refugees and other trauma sufferers, and some articles have even discussed music therapy among torture survivors, this is one of the first empirical research studies of music therapy specifically among patients who are survivors of torture. -

AWARDS PLATINUM ALBUM March // 3/1/18 - 3/31/18

RIAA GOLD & PLATINUM LOGIC // EVERYBODY AWARDS PLATINUM ALBUM March // 3/1/18 - 3/31/18 SZA // CTRL PLATINUM ALBUM In March, RIAA certified 199 Song Awards and 75 Album Awards. All RIAA Awards DEMI LOVATO // TELL ME YOU LOVE ME dating back to 1958, are available at GOLD ALBUM riaa.com/gold-platinum! Don’t miss the NEW riaa.com/goldandplatinum60 site celebrating 60 years of Gold & Platinum NF // PERCEPTION GOLD ALBUM Awards, and many #RIAATopCertified milestones for your favorite artists! JUSTIN TIMBERLAKE // MAN OF THE WOODS SONGS GOLD ALBUM www.riaa.com // // // GOLD & PLATINUM AWARDS MARCH // 3/1/18 - 3/31/18 MULTI PLATINUM SINGLE // 47 Cert Date// Title// Artist// Genre// Label// Plat Level// Rel. Date// R&B/ 3/15/2018 IT'S A VIBE 2 CHAINZ DEF JAM 3/14/2017 HIP HOP R&B/ 3/1/2018 CAROLINE AMINE REPUBLIC RECORDS 8/26/2016 HIP HOP SIDE TO SIDE 3/9/2018 ARIANA GRANDE POP REPUBLIC RECORDS 5/20/2016 (FEAT. NICKI MINAJ) 3/20/2018 HOW FAR I'LL GO AULI'I CRAVALHO SOUNDTRACK WALT DISNEY RECORDS 11/18/2016 MEANT TO BE (FEAT. 3/28/2018 BEBE REXHA POP WARNER BROS RECORDS 8/11/2017 FLORIDA GEORGIA LINE) BRUNO MARS & 3/28/2018 FINESSE POP ATLANTIC RECORDS 11/18/2016 CARDI B HEY MAMA (FEAT. PARLOPHONE/ 3/19/2018 NICKI MINAJ, BEBE DAVID GUETTA POP 11/21/2014 ATLANTIC RECORDS REXHA, & AFROJACK) 3/1/2018 SORRY NOT SORRY DEMI LOVATO POP ISLAND RECORDS 7/11/2017 R&B/ YOUNG MONEY/CASH MONEY/ 3/8/2018 FAKE LOVE DRAKE 10/24/2016 HIP HOP REPUBLIC RECORDS R&B/ YOUNG MONEY/CASH MONEY/ 3/8/2018 FAKE LOVE DRAKE 10/24/2016 HIP HOP REPUBLIC RECORDS R&B/ YOUNG MONEY/CASH -

Linda Davis to Matt King

Sound Extreme Entertainment Karaoke Show with Host 828-551-3519 [email protected] www.SoundExtreme.net In The Style Of Title Genre Linda Davis From The Inside Out Country Linda Davis I Took The Torch Out Of His Old Flame Country Linda Davis I Wanna Remember This Country Linda Davis I'm Yours Country Linda Ronstadt Blue Bayou Country & Pop Linda Ronstadt Different Drum Pop Linda Ronstadt Heartbeats Accelerating Country Linda Ronstadt How Do I Make You Pop Linda Ronstadt It's So Easy Country & Pop Linda Ronstadt I've Got A Crush On You Country & Pop Linda Ronstadt Love Is A Rose Country & Pop Linda Ronstadt Silver Threads & Golden Needles Country & Pop Linda Ronstadt That'll Be The Day Country & Pop Linda Ronstadt What's New Country & Pop Linda Ronstadt When Will I Be Loved Country & Pop Linda Ronstadt You're No Good Country & Pop Linda Ronstadt & Aaron Neville All My Life Pop / Rock Linda Ronstadt & Aaron Neville Don't Know Much Country & Pop Linda Ronstadt & Aaron Neville When Something Is Wrong With My Baby Pop Linda Ronstadt & James Ingram Somewhere Out There Pop / Rock Lindsay Lohan Over Pop Lindsay Lohan Rumors Pop / Rock Lindsey Haun Broken Country Lionel Cartwright Like Father Like Son Country Lionel Cartwright Miles & Years Country Lionel Richie All Night Long (All Night) Pop Lionel Richie Angel Pop Lionel Richie Dancing On The Ceiling Country & Pop Lionel Richie Deep River Woman Country & Pop Lionel Richie Do It To Me Pop / Rock Lionel Richie Hello Country & Pop Lionel Richie I Call It Love Pop Sound Extreme Entertainment www.SoundExtreme.net www.SoundExtremeWeddings.com www.CrocodileSmile.net 360 King Rd. -

Connotative and Denotative Meaning of Emotion Words

CONNOTATIVE AND DENOTATIVE MEANING OF EMOTION WORDS IN TWENTY ONE PILOTS’ BLURRYFACE ALBUM A THESIS Submitted to Letters and Humanities Faculty in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Strata One (S1) Degree in English Letters Department REYUNA LARASATIKA 1112026000107 ENGLISH LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE DEPARTMENT FACULTY OF LETTERS AND HUMANITIES SYARIF HIDAYATULLAH STATE ISLAMIC UNIVERSITY JAKARTA 2017 ABSTRACT REYUNA LARASATIKA, Connotative and Denotative Meaning of Emotion Words in Twenty One Pilots’ Blurryface Album. Thesis. Jakarta: English Language and Literature Department, Letters and Humanities Faculty, State Islamic University (UIN) Syarif Hidayatullah, May 2017. This research is discussing connotative and denotative meaning consisting in emotion words in the lyrics of Twenty One Pilots’ songs in Blurryface album. The songs are Heavydirtysoul, Stressed Out, Ride, Fairly Local, Tear In My Heart, Lane Boy, The Judge, Doubt, Polarize, We Don’t Belive What’s On TV, Message Man, Hometown, Not Today and Goner. The meaning of emotion words in those song imply the songwriter’s background. The emotion words are classified based on Robert Plutchik and Henry Kellerman’s book titled Emotion: Theory, Research, and Experiment. Then, those emotion words are analysed using semantics theory to find the meaning and how the songwriter’s background is implied. The method which is used in this research is qualitative method because the research is describing verbal data which is the words in the song lyrics. Keywords: emotion words, semantics, connotative meaning, denotative meaning, Twenty One Pilots i DECLARATION I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and that, to the best of my knowledge and belief, it contains no material previously published or written by another person nor material which to a substantial extent has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma of the university or other institute of higher learning, except where due acknowledgement has been made in the text. -

Songs by Artist

73K October 2013 Songs by Artist 73K October 2013 Title Title Title +44 2 Chainz & Chris Brown 3 Doors Down When Your Heart Stops Countdown Let Me Go Beating 2 Evisa Live For Today 10 Years Oh La La La Loser Beautiful 2 Live Crew Road I'm On, The Through The Iris Do Wah Diddy Diddy When I'm Gone Wasteland Me So Horny When You're Young 10,000 Maniacs We Want Some P---Y! 3 Doors Down & Bob Seger Because The Night 2 Pac Landing In London Candy Everybody Wants California Love 3 Of A Kind Like The Weather Changes Baby Cakes More Than This Dear Mama 3 Of Hearts These Are The Days How Do You Want It Arizona Rain Trouble Me Thugz Mansion Love Is Enough 100 Proof Aged In Soul Until The End Of Time 30 Seconds To Mars Somebody's Been Sleeping 2 Pac & Eminem Closer To The Edge 10cc One Day At A Time Kill, The Donna 2 Pac & Eric Williams Kings And Queens Dreadlock Holiday Do For Love 311 I'm Mandy 2 Pac & Notorious Big All Mixed Up I'm Not In Love Runnin' Amber Rubber Bullets 2 Pistols & Ray J Beyond The Gray Sky Things We Do For Love, The You Know Me Creatures (For A While) Wall Street Shuffle 2 Pistols & T Pain & Tay Dizm Don't Tread On Me We Do For Love She Got It Down 112 2 Unlimited First Straw Come See Me No Limits Hey You Cupid 20 Fingers I'll Be Here Awhile Dance With Me Short Dick Man Love Song It's Over Now 21 Demands You Wouldn't Believe Only You Give Me A Minute 38 Special Peaches & Cream 21st Century Girls Back Where You Belong Right Here For You 21St Century Girls Caught Up In You U Already Know 3 Colours Red Hold On Loosely 112 & Ludacris Beautiful Day If I'd Been The One Hot & Wet 3 Days Grace Rockin' Into The Night 12 Gauge Home Second Chance Dunkie Butt Just Like You Teacher, Teacher 12 Stones 3 Doors Down Wild Eyed Southern Boys Crash Away From The Sun 3LW Far Away Be Like That I Do (Wanna Get Close To We Are One Behind Those Eyes You) 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

H:\My Documents\Article.Wpd

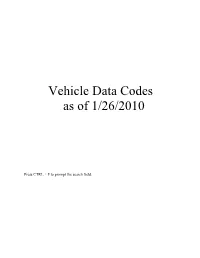

Vehicle Data Codes as of 1/26/2010 Press CTRL + F to prompt the search field. VEHICLE DATA CODES TABLE OF CONTENTS 1--LICENSE PLATE TYPE (LIT) FIELD CODES 1.1 LIT FIELD CODES FOR REGULAR PASSENGER AUTOMOBILE PLATES 1.2 LIT FIELD CODES FOR AIRCRAFT 1.3 LIT FIELD CODES FOR ALL-TERRAIN VEHICLES AND SNOWMOBILES 1.4 SPECIAL LICENSE PLATES 1.5 LIT FIELD CODES FOR SPECIAL LICENSE PLATES 2--VEHICLE MAKE (VMA) AND BRAND NAME (BRA) FIELD CODES 2.1 VMA AND BRA FIELD CODES 2.2 VMA, BRA, AND VMO FIELD CODES FOR AUTOMOBILES, LIGHT-DUTY VANS, LIGHT- DUTY TRUCKS, AND PARTS 2.3 VMA AND BRA FIELD CODES FOR CONSTRUCTION EQUIPMENT AND CONSTRUCTION EQUIPMENT PARTS 2.4 VMA AND BRA FIELD CODES FOR FARM AND GARDEN EQUIPMENT AND FARM EQUIPMENT PARTS 2.5 VMA AND BRA FIELD CODES FOR MOTORCYCLES AND MOTORCYCLE PARTS 2.6 VMA AND BRA FIELD CODES FOR SNOWMOBILES AND SNOWMOBILE PARTS 2.7 VMA AND BRA FIELD CODES FOR TRAILERS AND TRAILER PARTS 2.8 VMA AND BRA FIELD CODES FOR TRUCKS AND TRUCK PARTS 2.9 VMA AND BRA FIELD CODES ALPHABETICALLY BY CODE 3--VEHICLE MODEL (VMO) FIELD CODES 3.1 VMO FIELD CODES FOR AUTOMOBILES, LIGHT-DUTY VANS, AND LIGHT-DUTY TRUCKS 3.2 VMO FIELD CODES FOR ASSEMBLED VEHICLES 3.3 VMO FIELD CODES FOR AIRCRAFT 3.4 VMO FIELD CODES FOR ALL-TERRAIN VEHICLES 3.5 VMO FIELD CODES FOR CONSTRUCTION EQUIPMENT 3.6 VMO FIELD CODES FOR DUNE BUGGIES 3.7 VMO FIELD CODES FOR FARM AND GARDEN EQUIPMENT 3.8 VMO FIELD CODES FOR GO-CARTS 3.9 VMO FIELD CODES FOR GOLF CARTS 3.10 VMO FIELD CODES FOR MOTORIZED RIDE-ON TOYS 3.11 VMO FIELD CODES FOR MOTORIZED WHEELCHAIRS 3.12 -

Cannabis: Quels Effets Sur Le Comportement Et La Santé?

Cannabis : quels effets sur le comportement et la santé ? Sylvain Aquatias, Jocelyne Arditti, Isabelle Bailly, Marie-Berthe Biecheler, Monsif Bouaboula, Jean-Claude Coqus, Isabelle Grémy, Xavier Laqueille, Rafael Maldonado, Michel Mallaret, et al. To cite this version: Sylvain Aquatias, Jocelyne Arditti, Isabelle Bailly, Marie-Berthe Biecheler, Monsif Bouaboula, et al.. Cannabis : quels effets sur le comportement et la santé ?. [Rapport de recherche] Institut national de la santé et de la recherche médicale(INSERM). 2001, 432 p., tableaux, graphiques, références bibliographiques disséminées. hal-01570677 HAL Id: hal-01570677 https://hal-lara.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01570677 Submitted on 31 Jul 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Cannabis Quels effets sur le comportement et la santé ? Cannabis Quels effets sur le comportement et la santé ? ISBN 2-85598-800-4 © Les éditions Inserm, 2001 101 rue de Tolbiac, 75013 Paris Dans la même collection ¬ La Grippe. Stratégies de vaccination. 1994 ¬ Artériopathie des membres inférieurs. Dépistage et risques cardiovasculaires. 1994 ¬ Rachialgies en milieu professionnel. Quelles voies de prévention ? 1995 ¬ Sida, maladies associées. Pistes pour de nouveaux médicaments. 1996 ¬ Ostéoporose. Stratégies de prévention et de traitement.