Human Resource Specialist, US Army

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 September 2014 CHAPTER BULLETIN No. 73 1. MEETING SCHEDULE: Our Next Meeting Will Be

KENTUCKY AIRBORNE CHAPTER 82ND Airborne Division Association, Inc. “America’s Guard of Honor” 4913 Flushing Way, Louisville, KY 40272-3175 (502) 937-8234 Chartered by A Brotherhood Formed in Sweat and The United States Congress Blood 1 September 2014 CHAPTER BULLETIN No. 73 1. MEETING SCHEDULE: Our next meeting will be: Septembers' Meeting: 12:00 PM on 20 September, 2014 Summer Outing and Picnic Ruth & Russ Wilson's Place on the River 124 River Rd E, Charlestown, IN 47111 (See Attachment) Octobers' Meeting: 1:00 PM on 19 Oct, 2013 VFW Middletown Post #1170, 107 Evergreen Road, Louisville, KY 40243-1439 So mark your calendar and come on out for a little Airborne camaraderie and a good time. 2. WORD FROM THE CHAIRMAN: Greetings troopers! We've just returned from this year’s 82nd Assn Convention and it was a great time! For those of you who haven't made a local or national reunion you owe it to yourself to get to one. You won't regret it! Our own Joe "Devil" Steen is now a National Director, so congratulations Joe! Everyone remember that our next meeting will be September 20th 2014 at Ruth Wilson's house located at 124 River Road East, Charlestown, IN 47111. This will be our annual picnic and Ruth has requested that everyone bring a dish and to call her and let her know what you'll be bringing. Her phone numbers are 812-282-9006 or 502-938-1790. The chapter will provide hamburgers and hotdogs and some beverages. So everyone come on out and lets have a great time! We are looking good to host the convention in 2016 and we'll have more information about that at the meeting. -

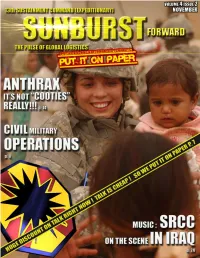

SUNBURST 1 Cover: Pfc

SUNBURST 1 Cover: Pfc. Theresa M. Marchese, a truck driver with D-Co., Forward Support Company, 1-167 Reconnaissance Surveillance and Target Acquisition, holds an Iraqi CONTENTS child as supplies are handed out Oct. 16. - Photo by Spc. Alexandra Hemmerly-Brown The SUNBURST is a monthly magazine distributed in electronic and print format. It is authorized for publication by the 13th SC (E) Public Affairs Office. The contents of the SUNBURST are unofficial and are not to be considered the official views of, or endorsed by, the U.S. Government, including the Department of Defense. The SUNBURST is a command information publication in accordance with Army Regulation 360-1. The Public Affairs Office is on LSA Anaconda on New Jersey Ave. in building 4136, DSN telephone: (318) 829-1234. Website at www.hood.army.mil/13sce. Contact Sgt. Joel F. Gibson via e-mail at [email protected] 13th SC (E) Commanding General Brig. Gen. Michael J. Terry 13th SC (E) Chief of Public Affairs Maj. Jay R. Adams COVER STORIES CIVIL MILITARY OPERATIONS p. 8 MANDATORY ANTHRAX VACCINATIONS p. 14 SRCC ON THE SCENE p. 24 NEW BEGINNINGS FOR AL BATHA CITIZENS p. 10 TROOPS HONE SKILLS AS COMBAT LIFE SAVERS p. 12 IRAQI GRADUATES FROM STUDENT TO TEACHER p. 15 AIKIDO.... WHAT’S THAT ABOUT p. 21 THE ZIGGURAT OF UR p. 28 2 SUNBURST SUNBURST 3 Back Page: Leaders from throughout the 45th Sustainment Brigade join Sol- diers who have reenlisted during deployment in celebrating a retention milestone Friday. - Photo by Sgt. 1st Class David E. -

Drop Zone32 Greetings from Puerto Rico26 One Army One

The official Magazine of T h e U . S . a r M y r e S e r v e SPRING 2011 one arMy one TeaM 20 A historical, unprecedented Army Reserve-lead, multi-component active duty sustainment brigade greeTingS froM pUerTo rico 26 The first-ever Army Reserve drill sergeant battalion on the island geT real 30 Medics train on a simulated battlefield where anything can Future Focus happen and does The Army Reserve as an 4 enduring Operational force in drop zone 32 an era of persistent conflict Learning how to properly get supplies to 2020 comrades overseas www.armyreserve.army.mil WARRIOR CITIZEN editor’s note ARMY RESERVE COMMAND TEAM Lt. Gen. Jack C. Stultz Chief, Army Reserve Chief Warrant Officer 5 James E. Thompson f you’ve ever wondered about the future Command Chief Warrant Officer of the of the Army Reserve and where we Army Reserve are headed, check out the Chief, Army Command Sgt. Maj. Michael D. Schultz Command Sergeant Major of the Reserve’s 2020 Vision and Strategy Army Reserve message on page 4. The nation and the Department of Defense are at a seminal WARRIOR-CITIZEN MAGAZINE STAFF point in U.S. history. Lt. Gen Jack C. Stultz shares Col. Rudolph Burwell I Director, Army Reserve Communications his vision and strategy for operationalizing the Col. Jonathan Dahms Army Reserve. The strategic decisions and direction chosen at this juncture sets the Chief, Public Affairs Division framework for the next decade and the future of the Army Reserve. Lt. Col. Bernd Zoller Chief, Command Information Branch In this issue we highlight the Soldiers of Task Force Provider, a rear provisional Paul R. -

Fifteenth Infantry Regiment

April 2018 Fifteenth Infantry Regiment “The Old China Hands” www.15thinfantry.org Dear Fellow Old China Hands, I hope all of you have survived winter and are enjoying spring weather, although in many parts of the country winter has been reluctant to relinquish its grip. I attended the 15th Infantry Regimental Ball hosted by 3-15 Infantry at the Savannah Marriott Riverfront on 6 April. It was a great event and you will get the details and photos in the article from the battalion in this issue. I would like to thank LTC Marks and his staff for organizing a wonderful evening that celebrated our Regiment’s unique history, traditions, and heritage. Guest speaker LTG Stephen M. Twitty, former China Six and former B/3-15 IN commander, delivered inspirational remarks on the 15th anniversary of the Thunder Run and TF 3-15 IN’s battles for Objectives Larry, Moe, and Curly. We were joined by Vice President Tad Davis, Mike Horn, CSM Mark Baker, and Korean War veteran Mr. David Mills and his wife Shirley. We were very happy to meet the incoming battalion commander, LTC Arthur McGrue, III, who is coming from 1st Army where he worked for LTG Twitty. He previously commanded B/1-15 IN during the Surge in Iraq in 2007! His military biography is included in this issue. We also met CSM Higley and his wife, Jillian, newly arrived from the Sergeants Major Academy. This command team promises to be another great tandem for the Association to work with. The Ball also fell on the 156th anniversary of the Regiment’s first major battle of the Civil War at Shiloh. -

Special Edition: Coordinating Staff Discusses Lesson Learned in This Issue

101st Sustainment Brigade Special edition: Coordinating Staff discusses lesson learned in thiS iSSue... “Managing YOUR Career” Page 4 “Strategic Sustainment Planning in Afghanistan Page 28 “Sustainment Brigades & Strength Management in a Modular Unit” Page 5 “The Building of Sustainment Brigades and the Inherent Issues Within” “Taking the HR Pulse of Your Company: Page 30 A guide for Commanders and First Sergeants” Page 6 “Managing Perceptions and Monitoring Relationships: Performing Informations Operations in a Sustainment Brigade” “The ‘Real’ Joint Sustainment Fight: Page 33 Integration of US Air Force Weather Support into US Army Sustainment Brigade Operations” “The Importance and Challenges Of Fostering Signal Relationships Page 7 As A Deployed Sustainment Brigade S-6” Page 37 “Incorporating Imagery Analysis into Sustainment Operations” Page 10 “Today’s Signal Soldiers and the Lack of Training” Page 39 “Preparing for and Executing Digital Mission Command in a Sustainment Brigade in Afghanistan” “Military Justice is Not a Substitute for Leadership” Page 12 Page 41 “Operational Risk Management” “Fobette Medic: Page 15 Mass Casualty planning on large forward operating bases” Page 44 “Logistics Reporting Tool” Page 17 “The Challenges of the Embedded Training Team Medical Mentor” “Bridging the Continuity gap one Sailor at a time” Page 46 Page 18 “The Three Most Common Electrical Safety Issues “Establishment of a Sustainment Brigade Plans Section (S5) in Deployed Environments” Page 19 Page 58 “Logistics Improvement to Increase Stability -

Enhancing Food Service Teams Vie for Army Connelly Award Bragging Rights

MILITARY CULINARY AWARDS Enhancing Food Service Teams Vie for Army Connelly Award Bragging Rights ach foodservice team competing for the annual Philip A. Connelly Award for Excellence in Army Food Ser- Evice is driven by its unique motivation to win, but all recognize that the key to success is the dedication of the soldiers and civilians working together. The Joint Culinary Center of Excellence (JCCoE) in 2014 presented awards to the best Army facility in each of there categories: large garrison, small garrison and field kitchen. While competitors are driven mainly by the challenge of winning and the prestige that comes with being recognized as the best in a category, that is not the only satisfaction. “Teamwork put us over the top; It couldn’t be done by just me or by any one soldier, it was a complete team effort,” said Sgt. 1st Class James Hardin, manager of the Courage Sgt. 1st Class James Hardin, the manager of The Courage Inn, a dining facility on JBLM, displays the 2014 Philip A. Connelly award for Excellence in Army Food Service in the large gar- rison category after an awards ceremony last September. The Courage Inn won again in 2015. (PHOTO COURTESY: STAFF SGT. ADAM KEITH, 19TH PUBLIC AFFAIRS DETACHMENT, 82ND SUSTAINMENT BRIGADE) MILITARY GARRISON **WINNER** 201st Battlefield Surveillance Brigade py to bring this award here,” Hardin said. Inn at JB Lewis-McChord Courage Inn Dining Facility Claiming the Large Garrison trophy (JBLM), Wash., after taking Fort Lewis, Wash. capped a year of training, but was time well first place in the Large Gar- spent as Hardin considers the recognition rison category of last year’s Connelly awards. -

2017 Sustainable Ranges

REPORT TO CONGRESS 2017 SUSTAINABLE RANGES Submitted by the Secretary of Defense Under Secretary of Defense (Personnel and Readiness) The estimated cost of this report or study for the Department of Defense is approximately $226,000 in Fiscal Years 2016–2017. This includes $162,000 in expenses and $64,000 in DoD labor. Generated on 2017Feb24 RefID: 7-8B07249 This Page Intentionally Left Blank. 2017 Sustainable Ranges Report May 2017 Table of Contents i Table of Contents Executive Summary ............................................................. 1 1 | Military Service Updates .................................................. 3 1.1 Army ................................................................................................................ 3 1.2 Marine Corps ................................................................................................... 9 1.3 Navy ................................................................................................................15 1.4 Air Force ........................................................................................................ 20 2 | Special Operations Forces Training Requirements ............ 25 3 | Military Service Range Assessments ............................... 27 4 | DoD’s Comprehensive Training Range Sustainment Plan ... 29 4.1 Goals and Milestones ..................................................................................... 29 4.2 Funding ........................................................................................................ -

Long Distance in the Desert Will Close Soon “This Is Obviously the Godfather of Marathons

Toby Keith to visit servicemembers this month ... stay tuned for more details MayANAC 2, 2007 PROUDLYNDA SERVING TIMES LSA ANACONDA Well-Done Full speed ahead Unit receives a taste of home Biathalon fun at cookout Page 7 Page 10 Vol. 4, Issue 17 Free tax help office on base Long distance in the desert will close soon “This is obviously the godfather of marathons. It’s history on it’s own right here” by Sgt. Alexandra Hemmerly-Brown - 1st Sgt. Joseph Brown Anaconda Times Staff See Page 15 LSA ANCONDA, Iraq - As tax season comes to a close, there is no need for servicemembers to worry about dwindling deadlines. Extensions are given and filing help is available here until May 15. “All deployed servicemembers automatically have a 180 day extension to file their taxes,” said Sgt. Bethany Becker of Hutto, Texas, the legal as- sistance noncommissioned officer in charge, 13th Sustainment Command (Expeditionary). “The 180 days starts when they redeploy.” There is also filing assistance for servicemem- bers on Anaconda, much like on any active duty Army base in the States. The consolidated legal center, located at building 9103, can help service- members prepare forms 1040a and 1040EZ. “We offer electronic filing of federal and state taxes,” Becker said. “If servicemembers have any other tax issues, I will do my best to help or find someone who can help them.” Assistance at the tax center is free, and if ser- vicemembers file their taxes using the E-file pro- gram, they can receive their refund in as little as 10 days, Becker said. -

US Military Casualties

U.S. Military Casualties - Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) Names of Fallen (As of May 22, 2015) Service Component Name (Last, First M) Rank Pay Grade Date of Death Age Gender Home of Record Home of Record Home of Record Home of Record Unit Incident Casualty Casualty Country City of Loss (yyyy/mm/dd) City County State Country Geographic Geographic Code Code ARMY ACTIVE DUTY AAMOT, AARON SETH SPC E04 2009/11/05 22 MALE CUSTER WA US COMPANY C, 1ST BATTALION, 17TH INFANTRY AF AF AFGHANISTAN JELEWAR REGIMENT, 5 SBCT, 2 ID, FORT LEWIS, WA ARMY ACTIVE DUTY ABAD, SERGIO SAGONI SPC E03 2008/07/13 21 MALE MORGANFIELD UNION KY US COMPANY C, 2ND BATTALION, 503RD INFANTRY AF AF AFGHANISTAN FOB FENTY REGIMENT, CAMP EDERLE, ITALY MARINE ACTIVE DUTY ABBATE, MATTHEW THOMAS SGT E05 2010/12/02 26 MALE HONOLULU HONOLULU HI US 3D BN 5TH MAR, (RCT-2, I MEF FWD), 1ST MAR DIV, CAMP AF AF AFGHANISTAN HELMAND CORPS PENDLETON, CA PROVINCE ARMY NATIONAL ABEYTA, CHRISTOPHER PAUL SGT E05 2009/03/15 23 MALE MIDLOTHIAN COOK IL US COMPANY D, 1ST BATTALION, 178TH INFANTRY, AF AF AFGHANISTAN JALALABAD FST GUARD WOODSTOCK, IL ARMY ACTIVE DUTY ACEVES, OMAR SSG E05 2011/01/12 30 MALE EL PASO EL PASO TX US 693D ENGINEER COMPANY, 7TH EN BN, 10TH AF AF AFGHANISTAN GELAN, GHAZNI SUSTAINMENT BDE, FORT DRUM, NY PROVINCE ARMY ACTIVE DUTY ACOSTA, EDWARD JOSEPH SPC E04 2012/03/05 21 MALE HESPERIA SAN CA US USA MEDDAC WARRIOR TRANSITION CO, BALBOA NAVAL AF US UNITED STATES SAN DIEGO BERNARDINO MEDICAL CENTER, SAN DIEGO, CA 92134 ARMY ACTIVE DUTY ACOSTA, RUDY ALEXANDER SPC E03 2011/03/19 -

13Th Sustainment Command Volume 10, Issue 3 (Expeditionary) FALL 2012

The Voice of Sustainment in CONUS Provider Base 13th Sustainment Command Volume 10, Issue 3 (Expeditionary) FALL 2012 LSOC Materiel Management Commander’s Corner C OLONEL Knowles Y. Atchison Greetings Teammates, About seven years ago LTG (R) Stevens wrote a white paper on “Where did my MMC go.” This was in response to many complaints the Army will not survive without Divisional and Corps level Material Management Centers. This has proven to be untrue of course, we still have all the capabilities of the MMCs and it’s just located in different places. Modularity has reshaped our force structure and after 9 years of heavy fighting on two fronts, we are not trying to reeducate our leaders on what right looks like.This would be fairly easy, except in the last ten years the Army established four Enterprise Systems; AMC (Material Enterprise), INSCOM (Installation Operations), FORSCOM (Readiness and Training) and TRADOC (Doctrine and Schools.) As we reset and retrain our Army back to a contingency based force, we are forced to merge three Enterprise Systems (AMC, FORSCOM and INSCOM) at the Installation level. The Sustainment Operations Centers (SOCs) that FORSCOM directed be setup on each FORSCOM Installation are merging these three Enterprise systems. The real power of the old MMC concept was not setting parameters on the SARSS boxes; it was clearly seeing the sustainment issues and bringing the right resources to bear on the problem. The SOC concept will do this. The other most powerful piece of the old MMCs was the analysis (the old R&A) that could be done to see and track trends. -

Autism Resources for Military Families

Autism Resources for Military Families Introduction: This is not an official or professional resource guide; it is a product of a High School Senior Graduation Project. This a list of resources in Fort Bragg and the surrounding areas, but that does not mean those listed are the only resources in the areas. Information, services, numbers, names, and addresses may not be up to date. It is recommended you research any service or resource listed or included in this booklet you are interested in to confirm they are accurate. Created by Madeline G. Walker Senior Graduation Project for Massey Hill Classical HS 1 Made in 2016 2 Special Thanks To my two mentors who guided me and my efforts through this project: Ms. Connie McCreary and Mrs. Trish Schnabel. To my mother and father who supported me in my effort, and my brother who inspired me to create this booklet. 3 Things you need to do when you move to the Fort Bragg area with a child with autism: Contact Army Community Service (ACS)/ Exceptional Family Member Program (EFMP) Complete prior research before moving to new location Contact Tricare if your region has changed, or if you are unsure if your region has changed Contact your Primary Care Manager (PCM) for any referrals or services needed, or if you suspect you have a child with autism 4 Families of a child diagnosed with autism may be eligible for the following services under TRICARE: Applied Behavioral Analysis Services Occupational Therapy (OT) Physical Therapy (PT) Speech Therapy Feeding Therapy Respite Care Audiology Testing Vision Testing Genetic Testing Neurology Testing Allergy Testing Sleep Studies Listening Therapy Assistive Technologies Services EDIS (Birth to 3 years of age) Contact your Primary Care Manager or Developmental Pediatrician 5 Table of Contents Applied Behavioral Analysis (ABA) Services ............................................. -

Fort Bragg Installation Guide and Answers Unlimited • 2014

Fort Bragg Installation Guide and Answers Unlimited • 2014 Dear Valued Customer, Army Community Service (ACS) is delighted to assist you with services, volunteer information, and training opportunities, which are available to you. ANSWERS UNLIMITED is one of many informative ACS products designed for your convenience to provide assistance in locating agencies and services on-post/off-post. Our corporate vision first in Soldier and Family support services sets the standard for a team oriented approach to excellence in customer service. It is our hope that your first stop upon arrival will be ACS. The ACS Mission is to provide commanders, Soldiers, and Family members with programs and services in a centralized location to enhance the quality of life. It is the goal of the entire ACS staff to provide professional customer service with genuine care while allowing you to utilize all the resources available to you. Sincerely, Barbara Trower-Simpkins Barbara Trower-Simpkins Director, Army Community Service WELCOME TO FORT BRAGG MAY YOUR STAY BE ENJOYABLE AND YOUR TOUR OF DUTY PROFESSIONALLY REWARDING. The ANSWERS UNLIMITED has been published since 1975. It is compiled and prepared by Army Community Service in the interest of all Fort Bragg Service members, Family members, civilian employees and community members. The Army Community Service staff and Volunteer Corps would like to thank all individuals who contributed to this issue. The ANSWERS UNLIMITED will be updated as needed, each time adding information that you, the military community, have requested or provided. Every effort has been made to provide accurate and current information. However, we recommend calling to verify location and hours of operation before visiting an agency.