Institutionalism As "Scientific" Economics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HLA MYINT 105 Neoclassical Development Analysis: Its Strengths and Limitations 107 Comment Sir Alec Cairn Cross 137 Comment Gustav Ranis 144

Public Disclosure Authorized pi9neers In Devero ment Public Disclosure Authorized Second Theodore W. Schultz Gottfried Haberler HlaMyint Arnold C. Harberger Ceiso Furtado Public Disclosure Authorized Gerald M. Meier, editor PUBLISHED FOR THE WORLD BANK OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS Public Disclosure Authorized Oxford University Press NEW YORK OXFORD LONDON GLASGOW TORONTO MELBOURNE WELLINGTON HONG KONG TOKYO KUALA LUMPUR SINGAPORE JAKARTA DELHI BOMBAY CALCUTTA MADRAS KARACHI NAIROBI DAR ES SALAAM CAPE TOWN © 1987 The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank 1818 H Street, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20433, U.S.A. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Manufactured in the United States of America. First printing January 1987 The World Bank does not accept responsibility for the views expressed herein, which are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the World Bank or to its affiliated organizations. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Pioneers in development. Second series. Includes index. 1. Economic development. I. Schultz, Theodore William, 1902 II. Meier, Gerald M. HD74.P56 1987 338.9 86-23511 ISBN 0-19-520542-1 Contents Preface vii Introduction On Getting Policies Right Gerald M. Meier 3 Pioneers THEODORE W. SCHULTZ 15 Tensions between Economics and Politics in Dealing with Agriculture 17 Comment Nurul Islam 39 GOTTFRIED HABERLER 49 Liberal and Illiberal Development Policy 51 Comment Max Corden 84 Comment Ronald Findlay 92 HLA MYINT 105 Neoclassical Development Analysis: Its Strengths and Limitations 107 Comment Sir Alec Cairn cross 137 Comment Gustav Ranis 144 ARNOLD C. -

The Institutionalist Reaction to Keynesian Economics

Journal of the History of Economic Thought, Volume 30, Number 1, March 2008 THE INSTITUTIONALIST REACTION TO KEYNESIAN ECONOMICS BY MALCOLM RUTHERFORD AND C. TYLER DESROCHES I. INTRODUCTION It is a common argument that one of the factors contributing to the decline of institutionalism as a movement within American economics was the arrival of Keynesian ideas and policies. In the past, this was frequently presented as a matter of Keynesian economics being ‘‘welcomed with open arms by a younger generation of American economists desperate to understand the Great Depression, an event which inherited wisdom was utterly unable to explain, and for which it was equally unable to prescribe a cure’’ (Laidler 1999, p. 211).1 As work by William Barber (1985) and David Laidler (1999) has made clear, there is something very wrong with this story. In the 1920s there was, as Laidler puts it, ‘‘a vigorous, diverse, and dis- tinctly American literature dealing with monetary economics and the business cycle,’’ a literature that had a central concern with the operation of the monetary system, gave great attention to the accelerator relationship, and contained ‘‘widespread faith in the stabilizing powers of counter-cyclical public-works expenditures’’ (Laidler 1999, pp. 211-12). Contributions by institutionalists such as Wesley C. Mitchell, J. M. Clark, and others were an important part of this literature. The experience of the Great Depression led some institutionalists to place a greater emphasis on expenditure policies. As early as 1933, Mordecai Ezekiel was estimating that about twelve million people out of the forty million previously employed in the University of Victoria and Erasmus University. -

Frank Knight 1933-2007 After Receiving His Ph.D

Frank Knight 1933-2007 After receiving his Ph.D. from Princeton University in 1959, Frank Knight joined the mathematics department of the University of Minnesota. Frank liked Minnesota; the cold weather proved to be no difficulty for him since he climbed in the Rocky Mountains even in the winter time. But there was one problem: airborne flour dust, an unpleasant output of the large companies in Minneapolis milling spring wheat from the farms of Minnesota. Frank discovered that he was allergic to flour dust and decided that he would try to move to another location. His research was already recognized as important. His first four papers were published in the Illinois Journal of Mathematics and the Transactions of the American Mathematical Society. At that time, J.L. Doob was one of the editors of the Illinois Journal and attracted some of the best papers in probability theory to the journal including some of Frank's. He was hired by Illinois and served on its faculty from 1963 until his retirement in 1991. After his retirement, Frank continued to be active in his research, perhaps even more active since he no longer had to grade papers and carefully prepare his classroom lectures as he had always done before. In 1994, Frank was diagnosed with Parkinson's disease. For many years, this did not slow him down mathematically. He also kept physically active. At first, his health declined slowly but, in recent years, more rapidly. He died on March 19, 2007. Frank Knight's contributions to probability theory are numerous and often strikingly creative. -

AN INVESTIGATION INTO the FORMATION of CONSENSUS AROUND NEOCLASSICAL ECONOMICS in the 1950S

THE ECLIPSE OF INSTITUTIONALISM? AN INVESTIGATION INTO THE FORMATION OF CONSENSUS AROUND NEOCLASSICAL ECONOMICS IN THE 1950s A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Julie Ragatz May, 2019 Committee Members: Dr. Miriam Solomon, Department of Philosophy Dr. David Wolfsdorf, Department of Philosophy Dr. Dimitrios Diamantaras, Department of Economics Dr. Matthew Lund, Department of Philosophy, Rowan University, External Reader © Copyright 2019 by Julie Ragatz Norton All Rights Reserved ii ABSTRACT The Eclipse of Institutionalism? An Investigation into the Formation of Consensus Around Neoclassical Economics in the 1950s Julie Ragatz Norton Temple University, 2019 Doctoral Advisory Committee Chair: Dr. Miriam Solomon As the discipline of economics professionalized during the interwar period, two schools of thought emerged: institutionalism and neoclassical economics. By 1954, after the publication of Arrow and Debreu’s landmark article on general equilibrium theory, consensus formed around neoclassical economics. This outcome was significantly influenced by trends in the philosophy of science, notably the transformation from the logical empiricism of the Vienna Circle to an ‘Americanized’ version of logical empiricism that was dominant through the 1950s. This version of logical empiricism provided a powerful ally to neoclassical economics by affirming its philosophical and methodological commitments as examples of “good science”. This dissertation explores this process of consensus formation by considering whether consensus would be judged normatively appropriate from the perspective of three distinct approaches to the philosophy of science; Carl Hempel’s logical empiricism, Thomas Kuhn’s account of theory change and Helen Longino’s critical contextual empiricism. -

Civil Law, Quadruple Entry System and the Presentation Format Of

Civil Law, Quadruple Entry System and the Presentation Format of National Accounts Kazusuke Tsujimura Masako Tsujimura July 20, 2008 ver.4.1 September 11, 2007 ver.1.1 K.E.O. DISCUSSION PAPER No. 109 Abstract One of the advantages of Roman law is simplicity. The quadruple entry system based on it gives a rigorous accounting framework to the system of national accounts when it is combined with historical cost accounting. Such a system retains all the desirable features of modern accounting: intra-sector, inter-sector and intertemporal consistency. The remarkable peculiarity of the system of national accounts is that it is the only statistics that depicts the interrelations between financial and real economy. The proposed scheme of this paper presents flows and stocks in an integrated framework, which makes it possible to clarify the relationship between savings and wealth and, therefore the relationship between income and wealth. This will enhance understanding of the interactivity between financial and real phenomena such as financial bubbles, crashes and depressions well within the domain of the system. Key Words System of national accounts; Historical cost accounting; Concept of income; Capital gain/loss JEL Classification Numbers A12; C82; E01 Acknowledgement The authors wish to thank Emeritus Professor Yoshimasa Kurabayashi of Hitotsubashi University, a former director of the United Nations Statistical Office, for his detailed and valuable comments to the earlier version of the paper. 1. Introduction The system of social accounting1 inclusive of the system of national accounts (SNA) has developed based on various fields of studies including economics, law and accounting. From the viewpoint of jurisprudence, the social accounting system stems from the civil code of Roman law, especially the Corpus Juris Civilis of Emperor Justinian2. -

GEORGE J. STIGLER Graduate School of Business, University of Chicago, 1101 East 58Th Street, Chicago, Ill

THE PROCESS AND PROGRESS OF ECONOMICS Nobel Memorial Lecture, 8 December, 1982 by GEORGE J. STIGLER Graduate School of Business, University of Chicago, 1101 East 58th Street, Chicago, Ill. 60637, USA In the work on the economics of information which I began twenty some years ago, I started with an example: how does one find the seller of automobiles who is offering a given model at the lowest price? Does it pay to search more, the more frequently one purchases an automobile, and does it ever pay to search out a large number of potential sellers? The study of the search for trading partners and prices and qualities has now been deepened and widened by the work of scores of skilled economic theorists. I propose on this occasion to address the same kinds of questions to an entirely different market: the market for new ideas in economic science. Most economists enter this market in new ideas, let me emphasize, in order to obtain ideas and methods for the applications they are making of economics to the thousand problems with which they are occupied: these economists are not the suppliers of new ideas but only demanders. Their problem is comparable to that of the automobile buyer: to find a reliable vehicle. Indeed, they usually end up by buying a used, and therefore tested, idea. Those economists who seek to engage in research on the new ideas of the science - to refute or confirm or develop or displace them - are in a sense both buyers and sellers of new ideas. They seek to develop new ideas and persuade the science to accept them, but they also are following clues and promises and explorations in the current or preceding ideas of the science. -

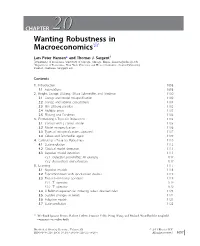

CHAPTER 2020 Wanting Robustness in Macroeconomics$

CHAPTER 2020 Wanting Robustness in Macroeconomics$ Lars Peter Hansen* and Thomas J. Sargent{ * Department of Economics, University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois. [email protected] { Department of Economics, New York University and Hoover Institution, Stanford University, Stanford, California. [email protected] Contents 1. Introduction 1098 1.1 Foundations 1098 2. Knight, Savage, Ellsberg, Gilboa-Schmeidler, and Friedman 1100 2.1 Savage and model misspecification 1100 2.2 Savage and rational expectations 1101 2.3 The Ellsberg paradox 1102 2.4 Multiple priors 1103 2.5 Ellsberg and Friedman 1104 3. Formalizing a Taste for Robustness 1105 3.1 Control with a correct model 1105 3.2 Model misspecification 1106 3.3 Types of misspecifications captured 1107 3.4 Gilboa and Schmeidler again 1109 4. Calibrating a Taste for Robustness 1110 4.1 State evolution 1112 4.2 Classical model detection 1113 4.3 Bayesian model detection 1113 4.3.1 Detection probabilities: An example 1114 4.3.2 Reservations and extensions 1117 5. Learning 1117 5.1 Bayesian models 1118 5.2 Experimentation with specification doubts 1119 5.3 Two risk-sensitivity operators 1119 5.3.1 T1 operator 1119 5.3.2 T2 operator 1120 5.4 A Bellman equation for inducing robust decision rules 1121 5.5 Sudden changes in beliefs 1122 5.6 Adaptive models 1123 5.7 State prediction 1125 $ We thank Ignacio Presno, Robert Tetlow, Franc¸ois Velde, Neng Wang, and Michael Woodford for insightful comments on earlier drafts. Handbook of Monetary Economics, Volume 3B # 2011 Elsevier B.V. ISSN 0169-7218, DOI: 10.1016/S0169-7218(11)03026-7 All rights reserved. -

The Transformation of Economic Analysis at the Federal Reserve During the 1960S

The Transformation of Economic Analysis at the Federal Reserve during the 1960s by Juan Acosta and Beatrice Cherrier CHOPE Working Paper No. 2019-04 January 2019 The transformation of economic analysis at the Federal Reserve during the 1960s Juan Acosta (Université de Lille) and Beatrice Cherrier (CNRS-THEMA, University of Cergy Pontoise) November 2018 Abstract: In this paper, we build on data on Fed officials, oral history repositories, and hitherto under-researched archival sources to unpack the torturous path toward crafting an institutional and intellectual space for postwar economic analysis within the Federal Reserve. We show that growing attention to new macroeconomic research was a reaction to both mounting external criticisms against the Fed’s decision- making process and a process internal to the discipline whereby institutionalism was displaced by neoclassical theory and econometrics. We argue that the rise of the number of PhD economists working at the Fed is a symptom rather than a cause of this transformation. Key to our story are a handful of economists from the Board of Governors’ Division of Research and Statistics (DRS) who paradoxically did not always held a PhD but envisioned their role as going beyond mere data accumulation and got involved in large-scale macroeconometric model building. We conclude that the divide between PhD and non-PhD economists may not be fully relevant to understand both the shift in the type of economics practiced at the Fed and the uses of this knowledge in the decision making-process. Equally important was the rift between different styles of economic analysis. 1 I. -

Glory Liu | Stanford University Writing Sample—Please Do Not Cite Or Circulate Without Permission Last Updated: June 2016

Glory Liu | Stanford University Writing Sample—please do not cite or circulate without permission Last updated: June 2016 Abstract: This paper is an excerpt from my dissertation on the reception of Adam Smith in American political thought and intellectual history (table of contents on next page), and focuses on the historical and intellectual forces in the twentieth century that produced an image of Smith as the “father of economics.” I argue that the Chicago School of Economics is largely responsible for producing an image of Smith associated with the politics and economics of American neoliberalism, and that this image emerged out of competing discourses around the nature of economic science from the 1930s onward. In the early 1930s and 40s, figures such as Frank Knight and Jacob Viner crafted an image of Smith as the intellectual forbearer of neoclassical price theory, and an economic science that could be “useful for guiding conduct.” From the 1950s onward, the generation of economists that included Milton Friedman, George Stigler, and Ronald Coase constructed an image of Smith associated with a narrower definition of economic expertise—namely, empirical testing, prediction, and its application to public policy. The notions of self-interest and “the invisible hand” became central to their approach, and ultimately opened the doors for the heavy politicization of Smith’s ideas. 1 Glory Liu | Stanford University Writing Sample—please do not cite or circulate without permission Last updated: June 2016 “Inventing the Invisible Hand: Adam Smith and the Making of an American Creed” Table of Contents and Chapter Summaries Chapter 1: Who was Adam Smith? This is an introductory chapter that outlines the scope of the project, provides a brief biographical sketch of the life of Smith and his immediate reception in Great Britain, and surveys current Smith scholarship. -

From the Progressives to the Institutionalists: What the First World War Did and Did Not Do to American Economics

From The Progressives to The Institutionalists: What the First World War Did and Did Not Do to American Economics Thomas C. Leonard Review essay on Rutherford, Malcolm (2011) The Institutionalist Movement in American Economics, 1918-1947: Science and Social Control, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 410 pp. ISBN: 9781107006997. $95. 1. Introduction Let me begin by recognizing Malcolm Rutherford’s achievement here. In 1998, Geoffrey Hodgson, writing in the Journal of Economic Literature, could say that we lacked an adequate history of Institutionalist Economics. No longer. Thanks to Rutherford’s long labors in the archives, begun before the 21st century was, we now have a splendid history of Institutionalist Economics, and more generally, of the Institutionalist movement, and of American economics between the wars. This is a meticulous, carefully crafted, brick by brick reconstruction of an important but misunderstood era in economic and social thought. At its very best moments, you feel like you are peering into a lost world. Rutherford has produced the new standard against which future contributions will be measured, and also to which historians of American economics will be obliged to respond. Our charge in this symposium is to respond. 2. What the book does The structure of the book is straightforward: we are introduced to the founding group and its students, and we are given compelling portraits of some neglected but important figures, Walton Hamilton and Morris Copeland, who stand in for the first and second generations, respectively. Next we proceed to the core of the book, the professional milieu of the Institutionalist economists, the “personal, institutional, and programmatic bases” of the movement in the Institutionalist academic strongholds – Chicago, Wisconsin, Columbia, Amherst, Brookings, and the National Bureau. -

![James M. Buchanan Jr. [Ideological Profiles of the Economics Laureates] Niclas Berggren Econ Journal Watch 10(3), September 2013: 292-299](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1091/james-m-buchanan-jr-ideological-profiles-of-the-economics-laureates-niclas-berggren-econ-journal-watch-10-3-september-2013-292-299-1021091.webp)

James M. Buchanan Jr. [Ideological Profiles of the Economics Laureates] Niclas Berggren Econ Journal Watch 10(3), September 2013: 292-299

James M. Buchanan Jr. [Ideological Profiles of the Economics Laureates] Niclas Berggren Econ Journal Watch 10(3), September 2013: 292-299 Abstract James M. Buchanan Jr. is among the 71 individuals who were awarded the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel between 1969 and 2012. This ideological profile is part of the project called “The Ideological Migration of the Economics Laureates,” which fills the September 2013 issue of Econ Journal Watch. Keywords Classical liberalism, economists, Nobel Prize in economics, ideology, ideological migration, intellectual biography. JEL classification A11, A13, B2, B3 Link to this document http://econjwatch.org/file_download/718/BuchananIPEL.pdf ECON JOURNAL WATCH James M. Buchanan Jr. by Niclas Berggren6 James M. Buchanan (1919–2013) was born in rural Tennessee under rather simple circumstances: “It was a very poor life,” he says (Buchanan 2009, 91). Still, he ended up, in 1986, as a recipient of the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel. The Prize was awarded “for his development of the contractual and constitutional bases for the theory of economic and political decision-making.” Buchanan earned his Ph.D. in economics from the University of Chicago in 1948 and was thereafter a professor at the University of Tennessee, Florida State University, the University of Virginia, UCLA, Virginia Polytechnic Institute, and George Mason University. In spite of his academic accomplishments, Buchanan felt himself to be apart from an established elite—academic, intellectual or political—and he even regarded that elite with suspicion. The attitude can be connected to Buchanan’s ideological convictions and how these changed over the course of his lifetime. -

ECONOMIC MAN Vs HUMANITY Lyrics

DOUGHNUT ECONOMICS PRESENTS . ECONOMIC MAN vs. HUMANITY: A PUPPET RAP BATTLE STARRING: Storyline and lyrics by Simon Panrucker, Emma Powell and Kate Raworth Key concepts and quotes are drawn from Chapter 3 of Doughnut Economics. * VOICE OVER And so this concept of rational economic man is a cornerstone of economic theory and provides the foundation for modelling the interaction of consumers and firms. The next module will start tomorrow. If you have any questions, please visit your local Knowledge Bank. POTATO Hello? BRASH Hello? FACTS Shall we go to the knowledge bank? BRASH Yeah that didn’t make any sense! POTATO See you outside. They pop up outside. BRASH Let’s go! They go to The Knowledge Bank. PROF Welcome to The Knowledge Ba… oh, it’s you lot. What is it this time? FACTS The model of rational economic man PROF Look, it's just a starting point for building on POTATO Well from the start, something doesn’t sit right with me BRASH We’ve got questions! PROF sighs. PROF Ok, let me go through it again . THE RAP BEGINS PROF Listen, it’s quite simple... At the heart of economics is a model of man A simple distillation of a complicated animal Man is solitary, competing alone, Calculator in head, money in hand and no Relenting, his hunger for more is unending, Ego in heart, nature’s at his will for bending POTATO But that’s not me, it can’t be true! There’s much more to all the things humans say and do! BRASH It’s rubbish! FACTS Well, it is a useful tool For economists to think our reality through It’s said that all models are wrong but some